Netflix, the largest online streaming medium with a large diversity of films and series in a variety of visual styles, are continually displaying their strong motives of adding animation titles from around the world to their vast video library. As part of that, they have been instrumental in bringing anime*1 titles to their huge, global audience, as well as producing original shows categorised as anime, such as the acclaimed series Devilman Crybaby (2018) directed by Masaaki Yuasa, who won the Cristal for Best Feature film at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival 2017 with the film Lu over the Wall. Netflix is also helping the evolution of animation by creating new anime-styled shows such as Castlevania (2017).

This year, many key people from Netflix came to the Annecy International Animated Film Festival and the International Animation Film Market (Mifa) to present their upcoming animation titles. They also showed that they are giving importance to anime by the program: “Netflix Original Anime: A Celebration of Anime and a Look Ahead”.

Animationweek is here today with John Dederian, director of Japan and anime at Netflix, to share with you Netflix’s strategy on the choice of anime titles to stream and produce.

*1: Here, we refer to “anime” as a style of animation with a unique visual style and elements that you can see in the majority of Japanese animated features and series.

Interview with John Dederian

Trayton Scott (TS): How do you decide which Japanese animation titles to stream? How do you decide whether to stream them globally or only within Japan?

John Derderian: We think about the potential audience for a title, so every time we go out to look for a title, we’re looking at the elements of the creators, the genre, the studio, a lot of different criteria we evaluate, and we see the fans and the fans in our members, and then what our future members would be interested in. So, when you look at a show like BAKI (2018), for example, we were really compelled that the IP was very strong, the style of the fighting show was very interesting, and would have a global audience beyond just Japan. Sometimes we do partnerships like BAKI where we have global rights.

Occasionally, we can’t access the global rights for a show, because of different issues of access. For example, maybe it’s been sold, or there’s companies that are invested in the production committee. Or it’s a show that we think has a unique appeal only in Japan. Generally, the appetite for anime in Japan is much broader than it is globally, where you see a narrower genre focus and interest.

We have a good amount of budget but it’s not unlimited, so we need to make choices on how we allocate that dollar best for our members.

TS: What are the results of streaming Japanese animation titles?

John Derderian: It’s a hugely important category for us, for several reasons. One, there is a truly global fandom for anime. What the streamers and Netflix, as part of that, are doing is solving a historical distribution problem for anime, where it wasn’t enormous in any one market, but if you accrue all those fans together, it’s actually quite large worldwide. So, that why it’s really important for us.

It’s also a category that works really well obviously in Japan, as well as other parts of Asia. So for us, it’s a priority to get really good and have the best shows. I don’t know about specific numbers, obviously different categories have different sizes of audience, but for us it’s worth investing. We keep growing our investment year after year and I’m sure we will continue to, because we see a lot of audience appetite for it.

TS: Do you have a different strategy for acquiring Japanese animation titles to stream on Netflix compared to American or European animation? How are they different?

John Derderian: There are three teams that do animation on Netflix. Original animation, kids & family, which focuses on that kind of audience. Adult animation, which does a lot of comedy programming primarily, but also some edgy animation. And then, anime.

Whatever is considered anime really has to be an anime-styled show, or certainly from Japan. Sometimes you have a show like Castlevania, which is created by non-Japanese artists and storytellers that love anime and really imbue the anime spirit. So for us we call that anime, because we think it’s done in the anime-style. For example, we have LeSean Thomas who we’re partnering with on two shows right now and one of them is Yasuke, in which he’ll work with MAPPA, a great studio in Japan. He’s not a native-born Japanese, he’s from the United States, but he is so deep in love of anime that we consider him a great anime creator.

Our group is programming primarily anime from Japan, such as Japanese anime and manga-based anime, but we’re also programming anime-styled shows from other parts of the world such as studios in other parts of Asia, for example.

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): There are some USA companies focusing on streaming only anime, like Crunchyroll and Funimation. Netflix has all kinds of content, including live-action films. What are your thoughts on the differences of your service? What differences will be made more prominent in the future?

John Derderian: We’re always going to be different from Crunchyroll or Funimation, because they’re focused on core fans. They live in a bit of a silo, where basically core anime fans enter the place and spend a lot of time there, and they’re super passionate about it. They also have a ton of anime, much more than we do.

The way we look at it is that we want the core fans to come to Netflix, and they are overlaps in the high subscribership between Crunchyroll and Netflix. A lot of people are subscribed to both. However, we also have this really interesting opportunity to find new fans for anime. When we think about that, we think about what’s the great stuff of anime, the great elements of anime that would excite someone to enter the medium and spend more time with it. And often that’s a heavy genre like sci-fi, fantasy, horror, action-driven fantasy, “Shonen” and “Seinen”projects.

We’re not trying to be Crunchyroll. I don’t think we need to be. We want the most of the best shows, and that’ll be through partnerships with the production committees, but it’ll also be through us, like we did with Devilman Crybaby, of just going to creators or studios or publishers and doing full originals for Netflix. So the goal for those is really to just have the best shows. Hopefully we’re good at picking them and if we can make a compelling proposition to the partner, we can get them.

HN: At the moment, anime titles on Netflix are more focused on animation for adults. As you know, there are really good anime for kids in Japan, like Doraemon. Do you have any plans to stream those kind of kids’ anime titles in the future?

John Dederian: We stream some of them. That would mostly be our original animation team, with kids and family, licensing this or creating that. If something is for under 10-year-olds, or a certain age limit, we would give it to that team because their overall programming is that category. We would potentially partner with them because we’re in Japan, but overall we’re excited about that type of programming like Doraemon and Crayon Shin-chan,fantastic properties that will be licensed and we would love to have our own versions of them, and the anime team would love to have our own versions of Naruto or One Piece. It’s really just the process of licensing great stuff that we don’t have the ability to make yet, but also trying to find the creators and the studios that can make the next Naruto. That would be a massive win for us, something we would be really excited about. Our subscribers and members would be thrilled to have us program that.

HN: Such as with Castlevania, some American artists are making anime-styled animation. Is there a possibility where you could bring American animation culture to Japan, for Japanese creators to make a new style of anime in Japan?

John Derderian: Anime for us is an art form, and if you look at music, there is amazing hip-hop in France, in Sri Lanka, there’s amazing Jazz in Ethiopia. Could classical music only be made in western Europe? Of course not. To me, when you have a great art form, it ultimately starts to transcend one culture or one country. Does that mean that Peru is going to be bigger than Japan in anime? No, anime will always have its home in Japan. That’s where it’s created, there will always be a great authenticity, and great passion, and great virtuosity to the creation of it. But, as any artform grows, I think there’s a benefit and an interesting element that happens when you get different points of view on it.

We’re not providing an opportunity for someone who knows nothing about anime to make anime. When someone like LeSean comes to us or Brad Graeber at Powerhouse Animation, or some of the great studios in Korea like Studio Mir. The people at these studios, all of them, know so much about anime and they have such love of anime that frankly it’s almost insulting to say they don’t make anime, because they’re so deep in the culture. So for us, we would love to facilitate that where we can, but also, I have to always say, I live in Tokyo, our whole team is based in Tokyo, we primarily make Japanese-based anime, with Japanese studios, manga-based, light-novel based, some game-based, all these things, that’s the core of what we do. I think this is another ‘tone’ of “oh wow, partnering LeSean with MAPPA, interesting.” That’s our viewpoint on it, we’re not on the soapbox about it, we do think it’s a great opportunity to create something fresh and interesting.

HN: So, you think the originality of each countries’ artists and studios, who understand and love anime a lot, are good elements for creating something fresh and interesting.

John Derderian: It’ll be something different, right?

We will have a new show, Eden, and Christophe Ferreira talked about the countryside in that show which was taken from Provence, a region in southeastern France. That’s unique, okay, that’s interesting. I mean, it’s set in a futuristic time, it’s not set in any one place, so that’s fair. To me it’s exciting when you have those kind of opportunities. We’ve only been here a day in Annecy, but we’ve met with about four European studios, they to me could be amazing partners with a great animation studio in Japan, and work with them and give some of their ideas and Japan gives some of their ideas. Now, some Japanese studios don’t want to do that, they are very creator-driven, and they want to do everything with it, and that’s fine. That makes sense for them. But maybe other studios will try that. Maybe it’s interesting, maybe it’s not. We’re not telling them what to do, they have to want to do it, right? That’s the way we’re looking at it.

If you talk to animators from Paris, and you’re in France, and then we invite them to Tokyo, that’s interesting. I think we can get a lot of creative fusion and something exciting can come from that. France, particularly, has a huge history of anime, from it being programmed here in the 70’s and 80’s, and then having a lot of French creators moving to Japan, which is very interesting.

We want to encourage global interest and participation in anime. Why would anime become stronger with that? Because it means more people will be watching anime around the world, and that’s going to raise all of the best producers and creators in Japan, including Production I.G. and BONES. They are all going to have more opportunities. That’s the theory.

HN: When was the first time you encountered Japanese anime culture?

John Derderian: It was actually in high school, in shop class*2, where there was an exchange student from Japan, and he had the Akira manga, and he would just read it. I was always so impressed with him, and he wasn’t translating it but he would walk me through it, so that was the first time I ever really encountered that. There was stuff I saw like Blade Runner (1982), I had reference points, but to me I thought that it was an amazing art form. And then anime I saw later, and stayed with it somewhat over time, but when I came to Netflix, I really dove in even harder.

*2: A class previously widespread in American education, also known as Industrial Arts class, where skills such as woodworking and carpentry are taught.

TS: Could you share any upcoming titles from Netflix originals that you can recommend?

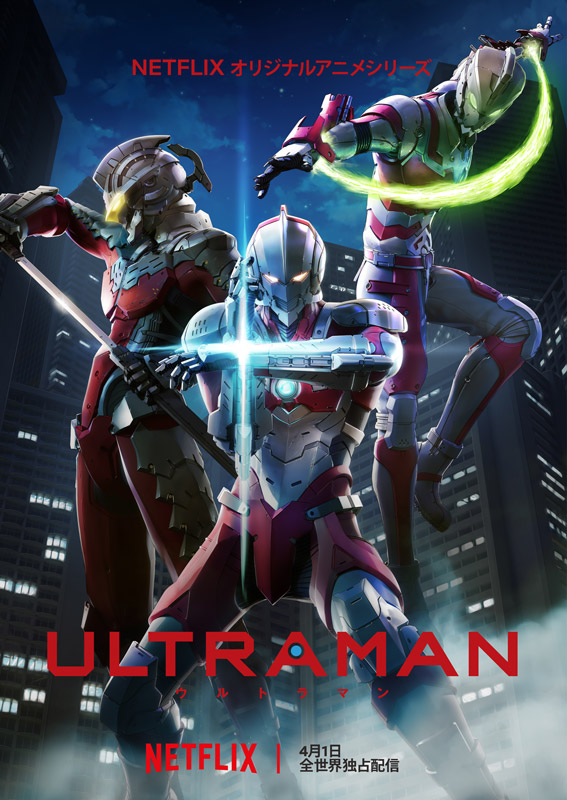

John Derderian: We have some great stuff, and we’ve obviously launched one already this year. It’s a season of anime for us, which really started from AnimeJapan*3 at Tokyo in March, going through Anime Expo at Los Angeles in July. We’ve successfully launched Ultraman, and Rilakkuma and Kaoru, both very well-known IPs especially in Asia. We got a show from a manga published by Shougakukan called 7SEEDS that will be developed with GONZO, a Japanese studio, which will be coming out and we are excited about that. And SAINT SEIYA: Knights of the Zodiac with Toei Animation, once again another beloved franchise that we think there will be a big global audience for.

Something that’s not an original for us that’s probably one of the biggest shows on our slate this year is Neon Genesis Evangelion, which is one of the greatest, most iconic sci-fi shows of any medium of all time that we’re very excited to bring to core fans, who’ve had problems accessing it in any great form, as well as for new fans who may have never heard of it.

One of the joys of Netflix is it being a general entertainment platform, so we have tons of people that don’t know that much about anime, but we can use the power of personalization to find them and to say, for example: “Oh, you love sci-fi shows, we see that you watch all these great live-action sci-fi shows. Then, you might like anime, because anime does stuff in sci-fi that’s very unique.” So, that is very exciting as well.

*3: You can read our special report articles on AnimeJapan 2019 linked below:

https://animation-week.com/spi04-animejapan2019-report01/

https://animation-week.com/spi04-animejapan2019-report02/

https://animation-week.com/spi04-animejapan2019-report03/