Folimage is a French animation studio based in Bourg-lès-Valence, France. The studio has been a driving force behind the growth of the French and European animation industry. At the center of this growth, there is always Jacques-Rémy Girerd, who founded the studio in 1981. Girerd has been leading Folimage and the animation industry with his strong originality, passion, and philosophy. Girerd recounts his journey and creative thought processes from his studio, Folimage.

The Founding of the Studio

How did you come into animation and decide to start your own studio?

I studied at the Beaux-Arts and learned painting and sculpture. I did a little experiment with animation using clay in the late 1970s, which was extremely rare at that time. People loved it, and they were really impressed.

I was encouraged at school to continue with animation. I made a very short film that was distributed all around the world. When you are young and people like your work, you just carry on. So I made a second film, then a third and so on. I made my first films in my kitchen, but then the time came when I had to create a production structure, a real studio, or find a producer in order to continue. At the time, however, nobody was interested in animation, and people didn’t really set up studios for themselves. The only solution was to become your own producer and create your own studio.

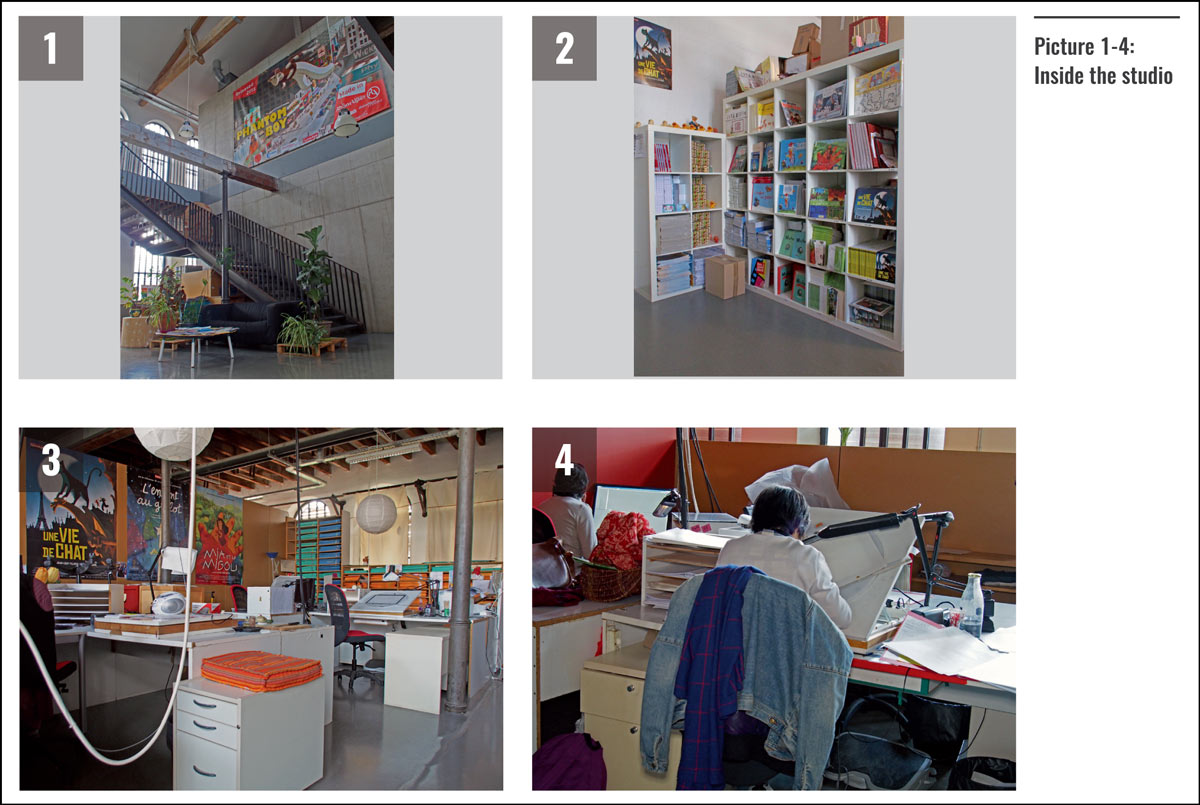

It didn’t make much sense to build a studio for just one person, so I started with friends. Other people gradually came on board, and it grew little by little. We had no particular plan, no preconceived idea of what the studio should become. It was simply built to create (authored)* films.

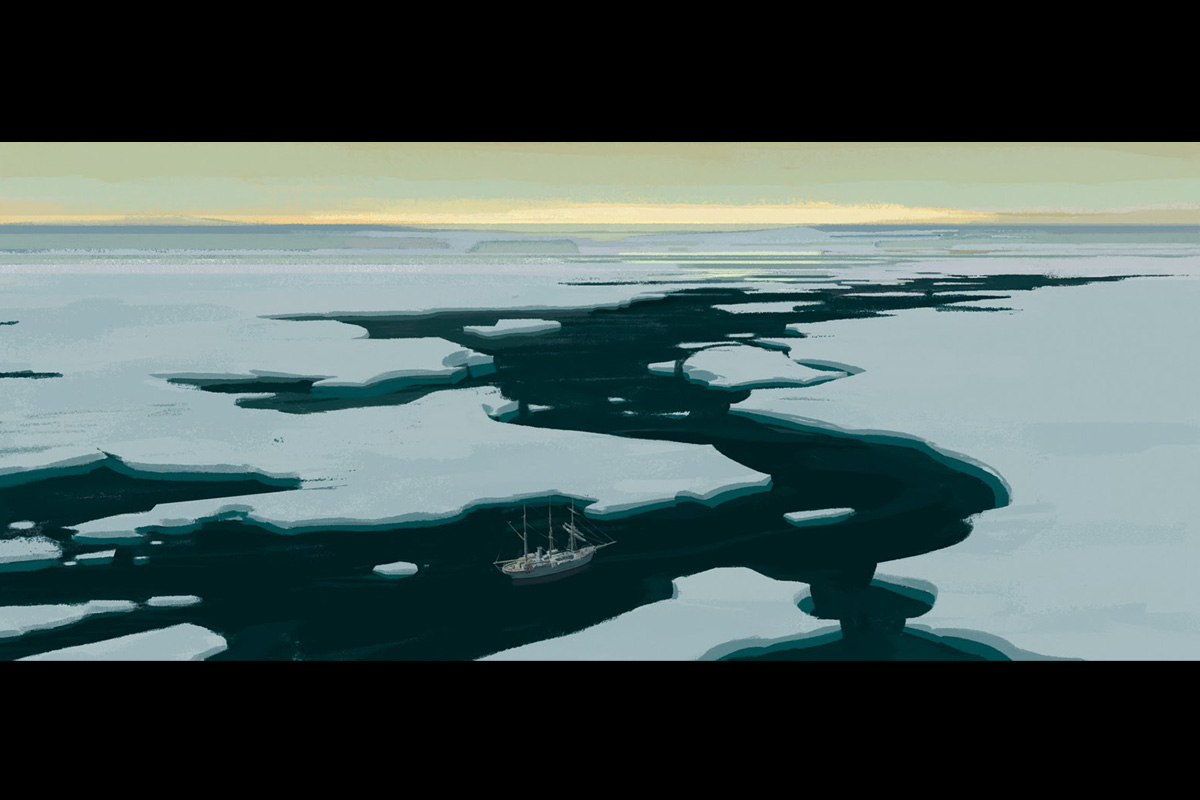

Naturally, we started by making short films. We were making original films of good craftsmanship, of good quality, very sentimental, that communicated well; the total opposite of being commercial. We built our reputation on high quality (authored)* films.

Growth of the Studio

After a while, it was economically difficult for us to keep the studio alive with short films. We began to create original series, but still (authored)** series for television as well. This gradually solidified the studio which allowed for its growth, expansion, and development, and the team has grown. Every year, we became little bigger and have grown to the state where about 130 people are at Folimage today.

When we started to make TV series and classic cartoons, everything was still made by hand in a traditional way, as computers did not really exist yet. It was extremely expensive to do so. We decided to transform the studio into a full-length feature animation studio. The studio was ready and mature enough for feature films.

The first feature film I directed and produced was Raining Cats and Frogs, and that was a global success. This success became much of the foundation of the studio. This offset the cash flow difficulties and the budget for TV series. So we were able to produce 5 or 6 feature films. Today, the situation is almost the opposite. It’s much more difficult to make feature films, and there are much easier and less expensive ways to produce series. So, the studio is reverting to making series.

You see, the studio was not guided by very formal goals like five-year plans. Rather, it was really to make high quality films that we were excited about, at the best we could. This was a driving force to get us together as a studio. People who worked on series were able to make short films. The money we earned, we immediately invested into producing films made by our team members.

*: Translated from the French ‘film de creation’.

**: Translated from the French ‘séries de création’.

Selecting Projects to Produce and Directors

How do you select the projects you produce at Folimage?

Today, we have an artistic committee, which is made up of creators and members of the production team. We examine all projects and there are three outcomes: 1) Either projects simply do not interest us; 2) In some cases, someone could be interested, we then discuss it with the author who had the original idea, and we sometimes allocate a mentor to push them to go further with their film, or; 3) If it is unanimous, it’s often the case that we produce films that the committee has fallen in love with.

There is a lot of collegiality at Folimage. I’m not the one to make decisions. It has never been one person who decides everything. It has been always shared, and decisions are made collectively.

How do you meet and find directors that you work with? Are they from Folimage, or do you search further afield?

Regarding the directors, they are mostly people from Folimage. For example, Alain and Jean Loup, whom you met, came to Folimage when they were young. They met each other while they were doing their civil service, when the military service still existed. They made a film, and we supported them and continued helping them. So it is often that people come here to do some work on an animation, and had their own projects. We tried to find ways to support them to do their projects. So, it’s usually been an internal promotion.

We also sometimes hire other directors like Regina Pessoa, who is a friend we know. She is Portuguese, and had a very beautiful project that was accepted in our program, La Résidence, a residency program which appeals to and is open to people all around the world. We provide the opportunity to those who are outside of our studio to produce a film. Another person who came to this program was Michael Dudok De Wit. He produced and directed The Monk and the Fish, and Father and Daughter, which won the Oscar in Hollywood.

So it has been a lot like that for 15 years. People came from all over the world. It did give the team motivation, and pulled the studio up to work with these great directors.

La Résidence is a program of about one-year, the time to make a film. Sometimes the time in residency lasted longer, in the case of Regina, it took 3 years for a 4 or 5 minute film.

Being a Militant and Making a Film Carrying a Strong Message

We think that your films portray political consciousness to a certain extent. They are full of messages, and give a voice to under-represented people. Is that something you do consciously or purposely? Or does this come from your team?

It is a bit like my mark, my signature. I was a militant, and I make films like a militant. I have things to say, I’m a witness of my time. I try to talk about the world around me, and it is important for my films to carry values and messages that don’t end up being pure entertainment. This has attracted like-minded people to our studio. They also have this desire to make films that have messages, an intention and a desire to change the world. It is the content which is the center of our films.

I think that this militant side of me is a consequence of the experiences in my background.

First, I studied medicine. Its application is represented in society. And then, I was also a teacher when I was studying fine arts, to pay for my studies. These two experiences, medicine and teaching, made me into the man I am, I think.

Could we ask you in a little more detail, how did studying medicine make you into a militant?

I think it comes from the fact that I studied the living. What I mean by that is, to be in contact with suffering, diseases, and life is no laughing matter. It’s not like welding iron. You’re working on the living. And as a teacher to convey the idea of sharing, the idea of educating children, and then to older students later on. I also taught in higher education. Being a teacher brought me this desire to be curious about others and to help them grow. For me, cinema is the same. It is also a medium that is used to share ideas, and also to help people grow. That’s why I say that I’m militant. Most of subjects I have talked about are related to life and the protection of life.

Developing a Story from an Original Idea

How do you develop stories from an original idea? Do you start with the characters? Do you start with other aspects?

I’m not too sure. Things come slowly. I think the process does tend to start with the characters and the urge to make them act, more than from ideas. For example, for the last film I made (Aunt Hilda!), the first thing I wanted to do was to have two female characters in leading roles. Obviously, you would not base your work on that. But it was a starting point, and the initial impulse was strong. After that, you should also work on ideas, but I think you’re right, I do tend to start by focusing on the characters, even if I sometimes end up adding or removing some.

It’s a bit like writing a theatre play. You create characters and you write dialogues, and somehow, the words and dialogues often build the story all by themselves. You’re like a pilot, navigating through, removing from, and carving into the story.

The Development of Visual Style

How do you decide on the graphic style for your films? They all look so different.

For a start, I haven’t always worked with the same graphic designers. The designers we worked with were far better than me, so I left them in charge of graphics. The idea, really, is to find graphics which fit with the text, not to use the graphics as a starting point for writing a story. Often, that’s the reason why films in the USA all look quite similar. They take a technique or an aesthetic and make something out of it. The reason why our films are so original is that we really try to apply graphics to the text, to the story. It’s sometimes a bit hazardous, we take risks every time. But it’s more interesting and creative.

I’m not saying the opposite isn’t good. Don’t get me wrong. In Japan, in particular, there’s Manga, a very strong graphical application, and that’s used to write stories. But for us, it’s different. It’s a matter of reinventing, re-enchanting the film’s graphics from a script.

Thoughts on 2D Animation

We would like to hear your thoughts on 2D animation. What makes producing and directing 2D animation attractive for you? And what would you say the future is for 2D?

If I were 20 or 25 years old today, I would certainly look into making 3D films, given the wealth of possibilities they offer, but not to the detriment of traditional graphic arts in 2D, which I think would be just as exciting to me as they are today.

At the time when I began working, personal computers weren’t around, and I found great pleasure in making 2D. It gives you a lot of freedom, I feel, a graphic freedom. We asked ourselves the question about producing 3D, and came to the conclusion that we still had a lot to explore with 2D. And since everyone is making 3D, what would be the point of doing the same thing as everyone else? So we held on to our authenticity, to our expertise. Since there aren’t many of us left, we thought that’s what we were best at, rather than having to learn everything all over again.

An Inspirational Trip to Japan

Let me tell you a story about my trip to Japan. When I was a young man and made my first film, I met Renzo Kinoshita at the Festival d’Annecy. He was the former Director of ASIFA Japan. ASIFA is the International Animation Film Association. It has representatives in every country. And he was the representative of Japanese animation. He said to me, “Here’s my number. If you ever come to Japan, call me”. I really wanted to go to Japan. I was very young. So I went to Japan, and on the second evening, I called this man. He invited me out. We went to the Ginza district in Tokyo, with all its bars, the sake… I was in a bit of a haze. I don’t know what happened, but when I got back to my hotel, I’d lost all my money. I had nothing left!

I was staying in a little hotel in Tokyo, very small but very tall. The owners were a young married couple. They made me an offer, “Cook us a French meal once a week and we’ll give you free food and accommodation in return”. I stayed for two months. I was able to visit all sorts of places, and that’s when I met Hayao Miyazaki at the studios for the first time. It was 1980, I think. He’s partly responsible for where I am today.

In what way did Miyazaki inspire you?

I believe Miyazaki was at the Toei Company when I met him. Seeing the work he went on to do really convinced me to pursue this career.

We also hosted Isao Takahata, here in Folimage. It was a long time ago, probably 20 years ago. We loved his work, and he has been a guide for us.

Would you say that Japanese animation had the greatest influence on your work?

There are also other influences such as Yuri Norshteyn in Russia or Frédéric Back in Canada, who also guided me. Initially, I did not go to Japan for animation specifically, but rather to explore Buddhism and Japanese traditional art. But as luck would have it, I met Kinoshita in Annecy and visited some studios. It all helped me to shift my perspective.

(Originally interviewed in French)