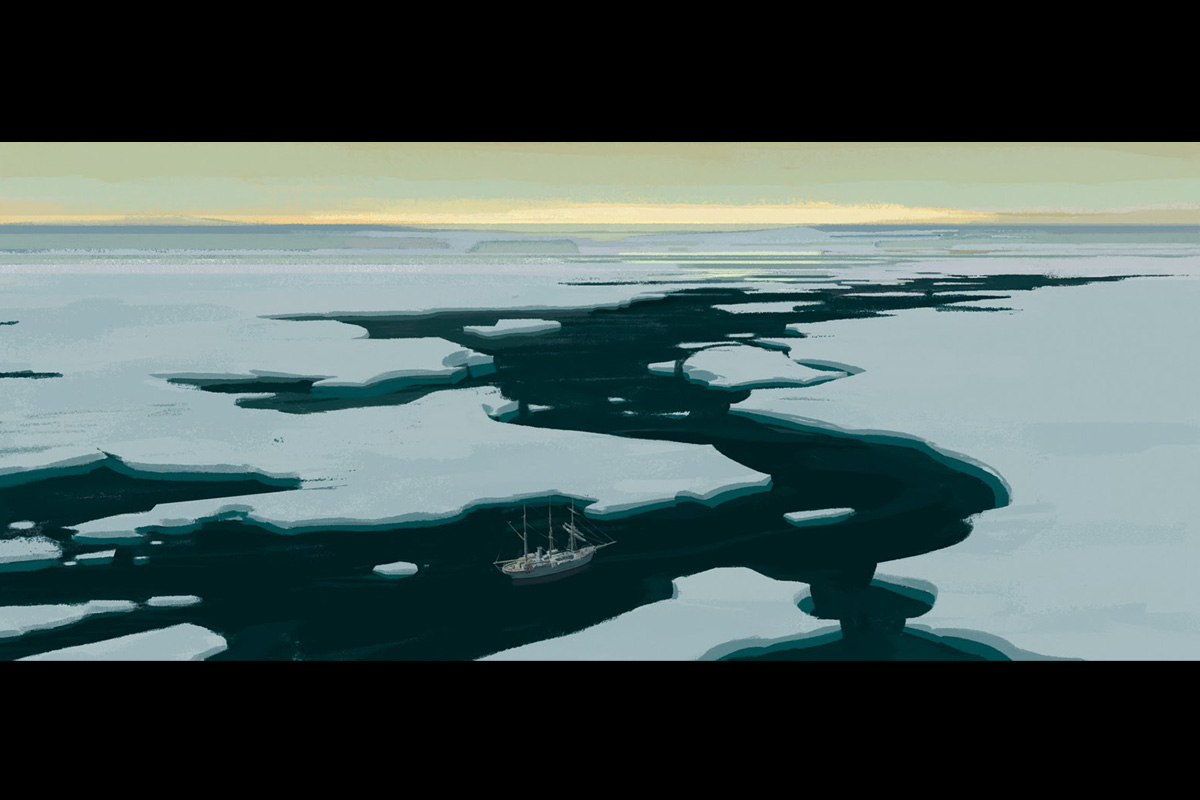

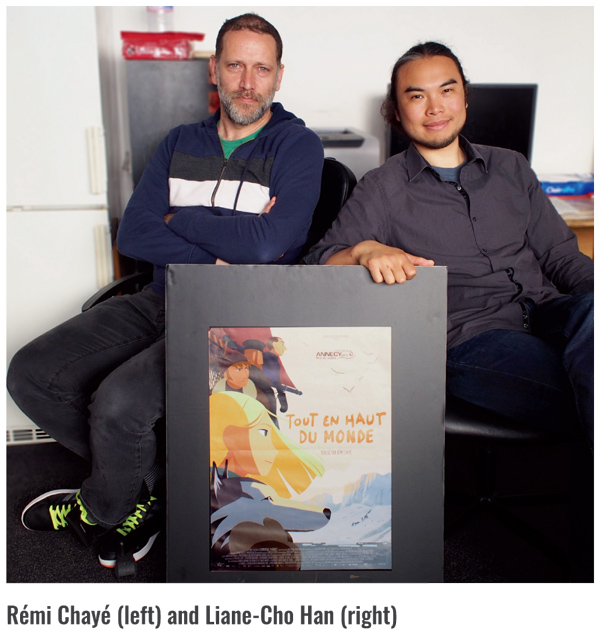

Long Way North is a beautifully told and visually stunning film. It is about a young Russian aristocrat named Sasha, who goes on an epic adventure to the North Pole to find out what happened to her grandfather and save her family’s honour. It was produced by the French studio Sacrebleu productions along with co-producers including French studio Maybe Movies and Danish animation studio Nørlum. We met with Rémi Chayé (the director of the film) and Liane-Cho Han (the animation director) to ask how this beautiful film came to life.

The Start of a Career in Animation

We first asked about Chayé and Han’s journey to start working in the animation industry as director and be a part of this film. For Chayé, drawing has been his passion since his childhood. He says, “I was passionate about comic books and I wanted to be a comic book artist, which was the plan when I went to art school.” After graduating from art school, he had been working as an illustrator for a while, but work from animation came to him at one point when he had no work, and then animation stayed with him forever afterwards. It was one of his friends who recommended him to go to an animation studio who was looking for people who know how to draw. “I went there and I never left the animation studio (laughs), because it was so cool!”

He developed his career in animation since then. From 1995 to 2004, he worked as a technician and a supervisor for animated films, mostly serials, TV series and TV specials. During this period, he started being asked to direct small films here and there. However, he felt that he was not skilled enough to do it, which led him to going to La Poudrière, a prestigious animation school in France dedicated in providing specialised education to prospective animation directors. He recalls his time at the school was great and it was in his early 30s.

In case of Han, he says that he is lucky to be able to watch such a variety of animated content from his early age, especially Japanese animation like Dragon Ball. Watching diverse animation had a big influence on his generation in France. His affection for animation leads to discovery of animated features such as Princess Mononoke (1997) and Grave of the Fireflies (1988) in his teenage years.

He recalls his encounter with these animations, “It was really a huge shock. I wanted to draw and work on these kind of things. But it wasn’t really clear in my head that it was animation. I just wanted to work on that and I didn’t draw at the time, it was only my sister, who drew since she was little.” After graduating from high school, he decided to draw. He says, “I had to learn how to draw in a very short period of time. I had to work very, very, very hard. It was very difficult to be accepted to Gobelins, very, very, difficult.” He never gave up, and managed to become accepted at Gobelins, which is one of the top animation schools in France, after his hard work while failing admission three times. At his time at Gobelins, he discovered the animation industry and acquired the skill to animate.

The Encounter between Chayé and Han

Their encounter goes back to the early stage of Long Way North. Han remembers his first meeting with Chayé back in 2011. Han says, “I had a friend working on the Long Way North pilot at that time, and wanted to visit the studio to see the project, and I showed Rémi my animation demo reel, and he was really interested. But at that time I wasn’t storyboarding, I was actually learning, and I remember I showed him a storyboard test and he said, ‘It’s quite bad!’ and ‘You should learn a bit more’ (laughs).”

Han had gained experience as a storyboard artist since then. Two years later in 2013, he received another opportunity, where Chayé was looking for storyboard artists. Maïlys Vallade, who was working on the storyboard of Long Way North, convinced Chayé to see Han. That is when Han showed his work to Chayé, and Chayé was pleased with Han’s work. This is how they came to work together. Han started as a storyboard artist when he joined the project and moved up to an animation director for the whole team later on.

More than 10 Years in Bringing the Film to Reality

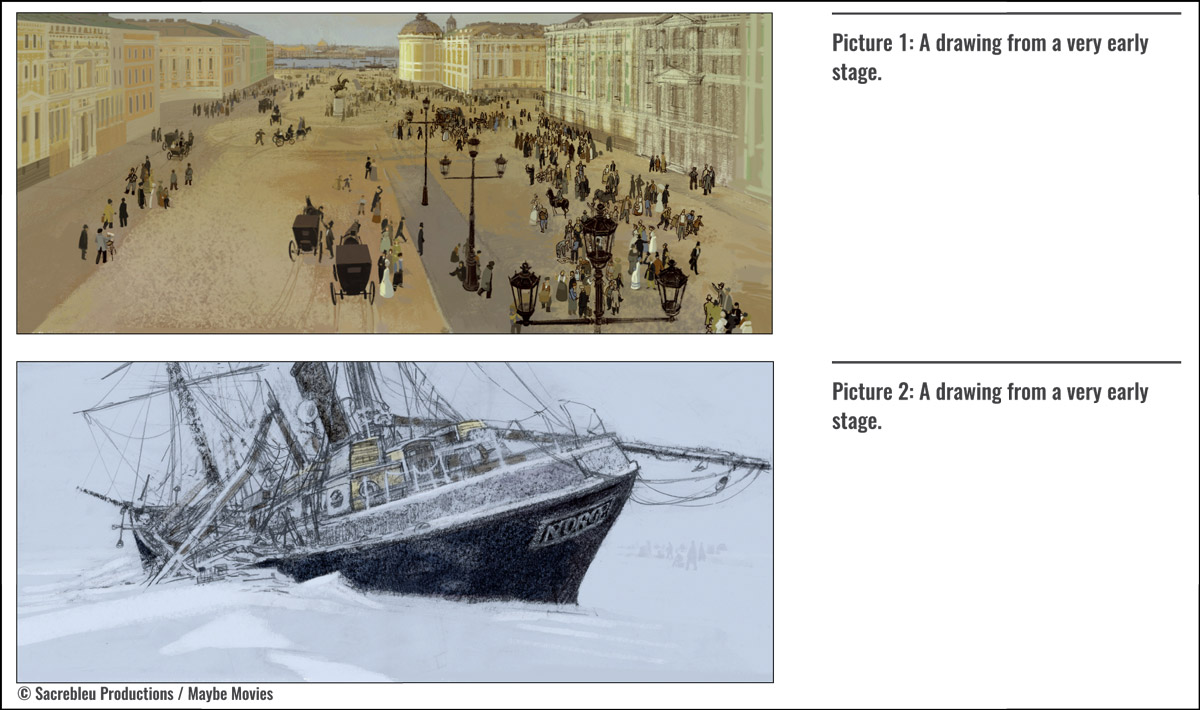

In 2005, the idea of the project had first emerged when Chayé was at La Poudrière. Claire Paoletti, a scriptwriter, came up to Chayé with the original script idea on one sheet of A4-sized paper. Chayé was able to see the mood and the final image of the film from that paper as it was already expressed there. After that, they started working like playing ping-pong between text and drawings and it continued for several years.

The story of Long Way North was inspired by Northern Lights by Philip Pullman, which Chayé recalls from his conversation with Paoletti. Chayé explains that Northern Lights was a starting point and developed a story with extensive research, being inspired by various things.

“It’s a very nice novel for children, and it’s with a very nice female character. So, the idea at the beginning was to have a female character, a teenager, thinking that younger children could identify themselves with her. The other inspirations came from loads of things, like the Shackleton Expedition, Amundsen Expedition, and all the expeditions from the 19th century, a lot of different expeditions for the North Pole or the South Pole. We also had inspiration from Russian paintings. It took 10 years. We had loads of time to read and look at plenty of documentations.”

The script went through several revisions. “The first script was not good, it was complicated and had tons of basic mistakes in it. We had the help of a second scriptwriter, and then a third one. The scriptwriting had been done three different times, maybe more for each scriptwriter. Basically, we had problems with Sasha because she is a teenager. She had to run away from her parents, and the problem was not to feel that she was a needy girl, but that she did it for good reasons. We had to find a plot that would push her to the North Pole – those were the hardest things”, Chayé says.

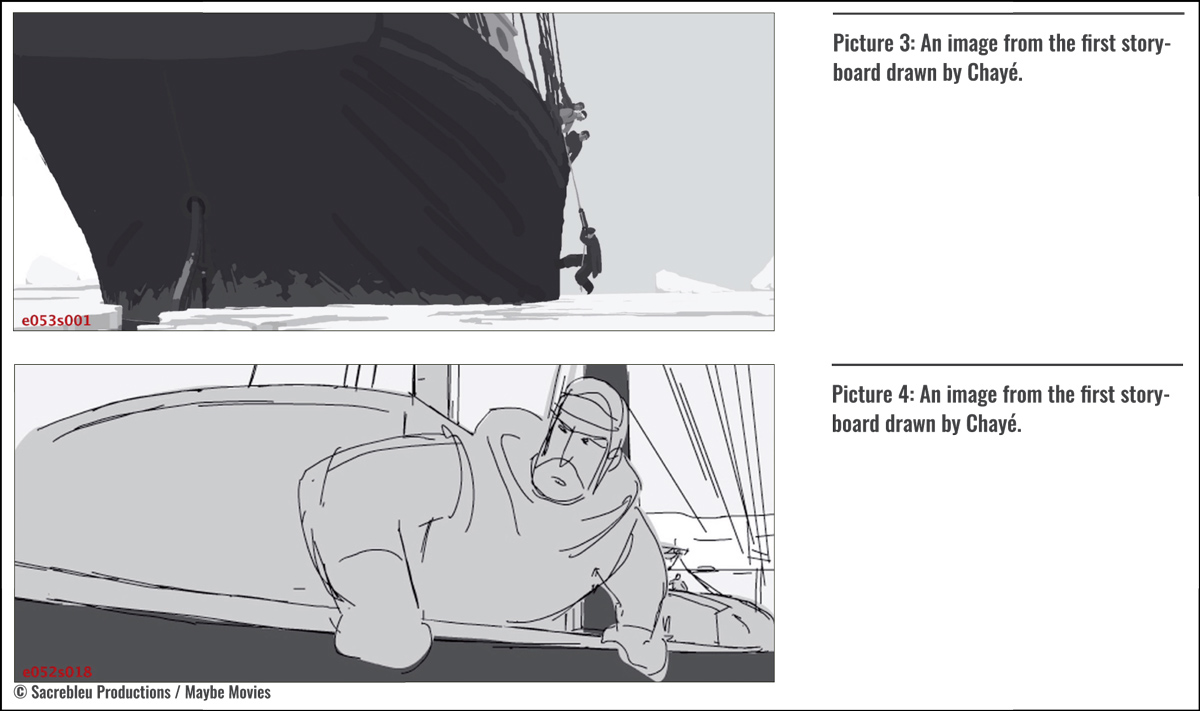

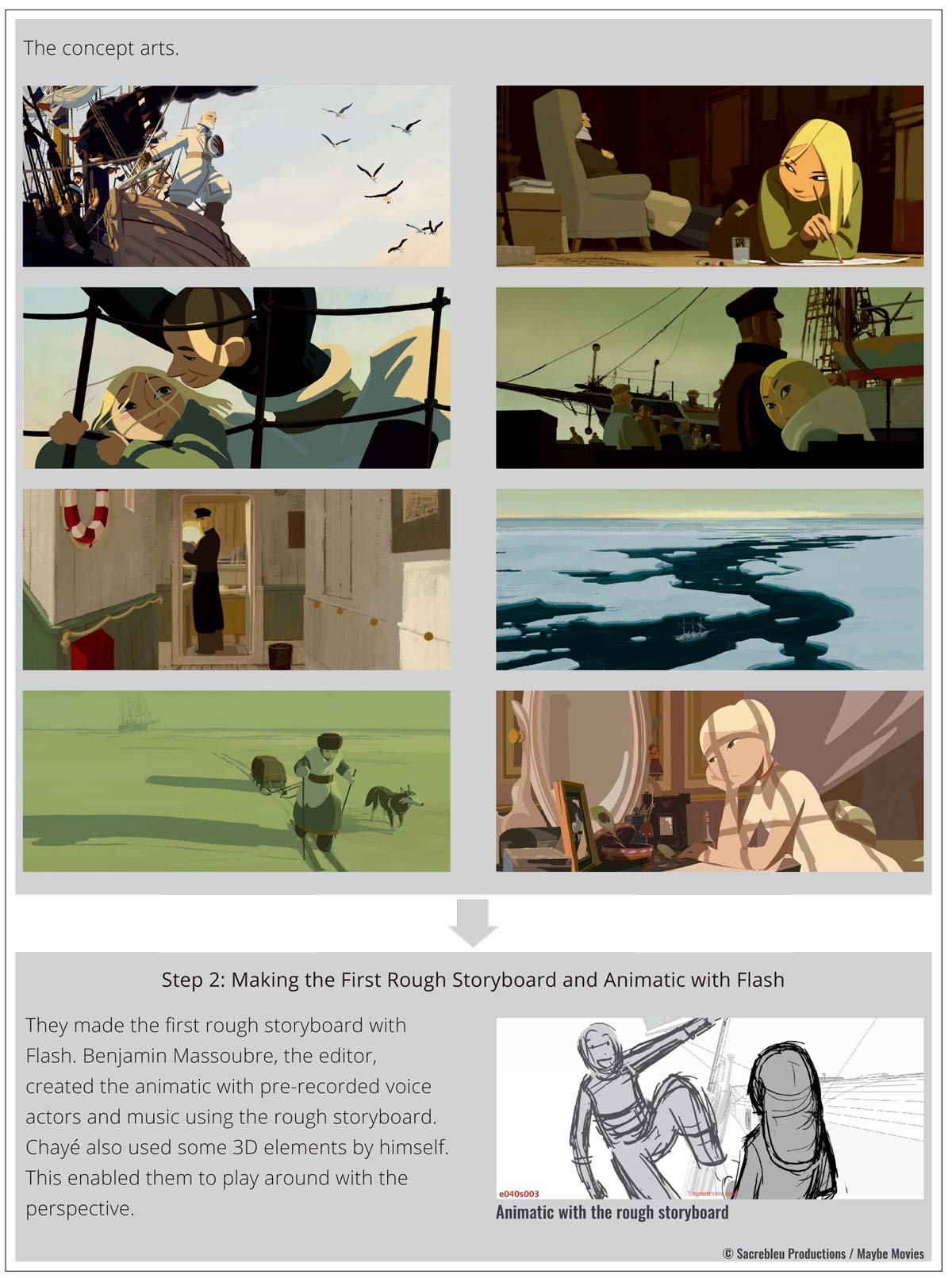

Deploying a New Approach for Story Development

A struggle with scriptwriting led to a new approach to make the story right. While they were deciding to hire a third scriptwriter, Chayé started drawing a wall of storyboard panels in parallel. It required numerous amounts of work. “We had communication back and forth with Benjamin Massoubre, the editor. It was a small team, very creative and very keen on the whys, hows, and how to push it, how to make it better and better. So, it was really at that point that the story was really done, that was the most interesting part of the job at least.”

Characters were also shaped during this process and Chayé says it is a result of great collaborative work. “Actually, the scriptwriter, Fabrice de Costil, had a very good idea about the characters, how they compete with each other, and how they match. For example, he came up with the idea that Lund and Larson were brothers, they were not at the very beginning, and finally they were. The story developed in an interesting way when they were brothers and they had relationship problems between themselves. It drove us to very interesting situations related to Sasha’s problem. It was really, really cool – those sorts of things.”

The Importance of Storyboard Artists

Chayé has his own theory about the crucial role of storyboard artists. He articulates, “I’ve seen a lot of storyboard artists who express story very nicely. Storyboard artists are actors and they are completely inside of the work. You read the script, make your movie in your head, you’re completely in the situation and you draw something, an expression, like Sasha smiling or crying. The posing is strong and very nice, but the designer decides that this is not Sasha’s smile, Sasha will have to smile like this… And the designer very often works outside the circle and the situation. Very often I felt that the drawings of the storyboard artist were more accurate than the ones of the designers. I was sad sometimes that some beautiful expressions would disappear because of corrections based on character design. ‘She has to smile like this‘, and I had to correct that nice expression and make it like the way the designer decided. What I started to organise was using the storyboard artist’s drawings to define the style, which is completely possible during the process.”

Han says, “At least for Rémi, Maïlys and me, we know storyboard, animation, and posing. This is very good. Even better, since Rémi, as a director, was also the supervisor of the background layouts. Even when you have a very rough storyboard for the background, he could see what the storyboard was about and the camera angle used.” He continues, “Rémi could interpret it in the most accurate way to make the best composition. If it was someone else, a person who does not have much experience with storyboards, he wouldn’t have this understanding of the storyboard as accurately as it should be. In the case of Rémi, he is different from that kind of person. He is connected to the storyboard. He worked on storyboards and supervised the background layout. He knew the best solution.”

Chayé says, “We knew exactly what were in sequences and why. Sometimes where Liane-Cho and the other storyboard artists had to work, it was about staging, was about what ingredient to put in those scenes to make it better. For example, I remember Liane-Cho came up with the idea that Sasha had to be kissed because she’s in the snow, that sort of thing. That put more and more cinematic and interesting situations. It was really something that goes back from the editor to the scriptwriter through to the storyboard artist. It was really team work.”

For Han, this process can be described like putting muscles on a good skeleton. Storyboard artists, including Han together with Chayé, has enriched the story on the basis of the script. “We created situations to maybe make things more interesting, to create more empathy for the characters, and deepening the relationship. The story was obviously created by the scriptwriter but we storyboard artists developed more. It is because scriptwriting was a bit in a rush and the scriptwriter necessarily didn’t have the time to develop further. I think it’s a mixture of the American and Japanese styles of the animation production process.”

Han explains: “What is meant by American and Japanese style is the difference in how storyboards are created in these two countries. In Japan, a director tends to have full control over the storyboard and he draws a storyboard following his vision. Contrary to that, in America, a lot of storyboard artists, like 20 of them, are involved in the process. Each storyboard artist draws a storyboard of a sequence allocated by a director based on a script. Each one of them tries to sell their ideas. A director will choose the ideas and decide which ones to take. It’s more of a teamwork.”

Chayé and Han agree that France would sit in the middle between Japan and America. In the case of Long Way North, storyboard artists try to find the right ideas to follow the director’s vision. Han says, “Rémi was the director, who was also a storyboard artist, and he was working on the script. He almost had full control of the movie like the Japanese but, at the same time, he has a team who gave ideas which he can also use.”

Chayé adds, “What happened is, very often we were changing sequences with Liane-Cho and Maïlys, it meant that I would start a scene and I would say to him, ‘I don’t feel that it’s right, that’s not good.’ He’d say, ‘Okay, give me that for one or two days, and I’ll draw plenty of things.’ And then I’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s good, oh yeah that’s a very good idea!’ I would take the sequence back and draw something else. He’d say, ‘Oh no, that’s not good, I don’t like that!’ And he’d take it from me and start to draw again… So it was really something like that, very much about teamwork, even on the same sequence.”

They had this very open and good relationship as a team which resulted in the engaging story.

Visualisation

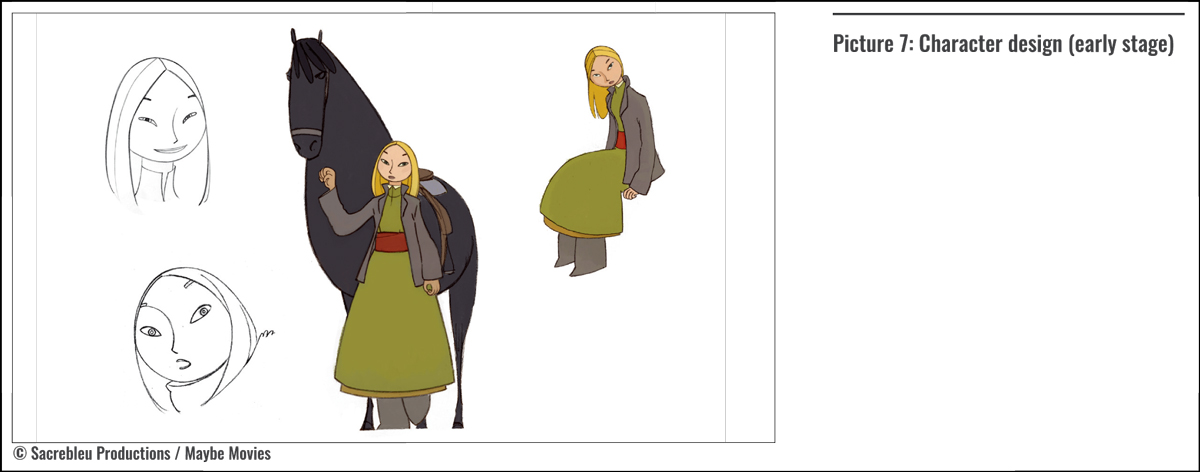

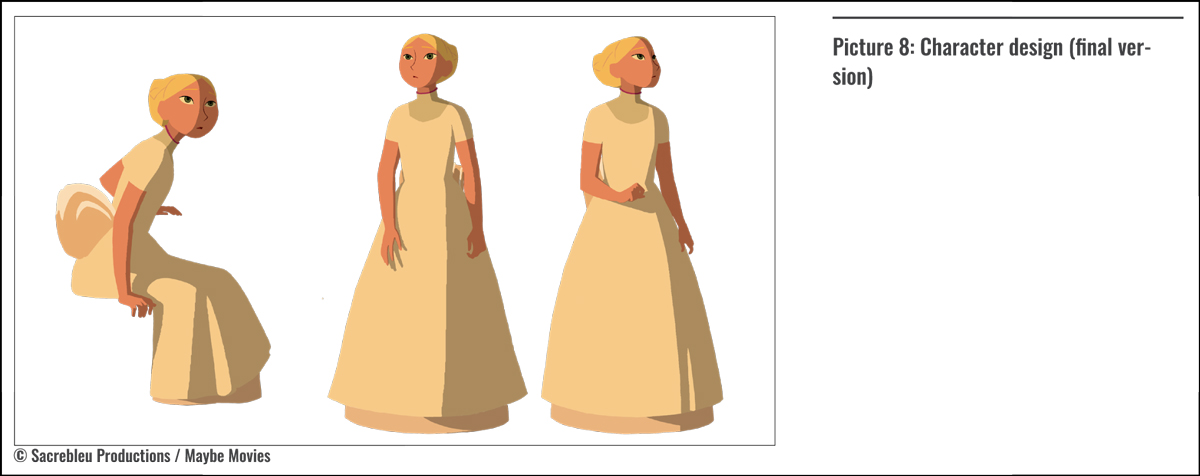

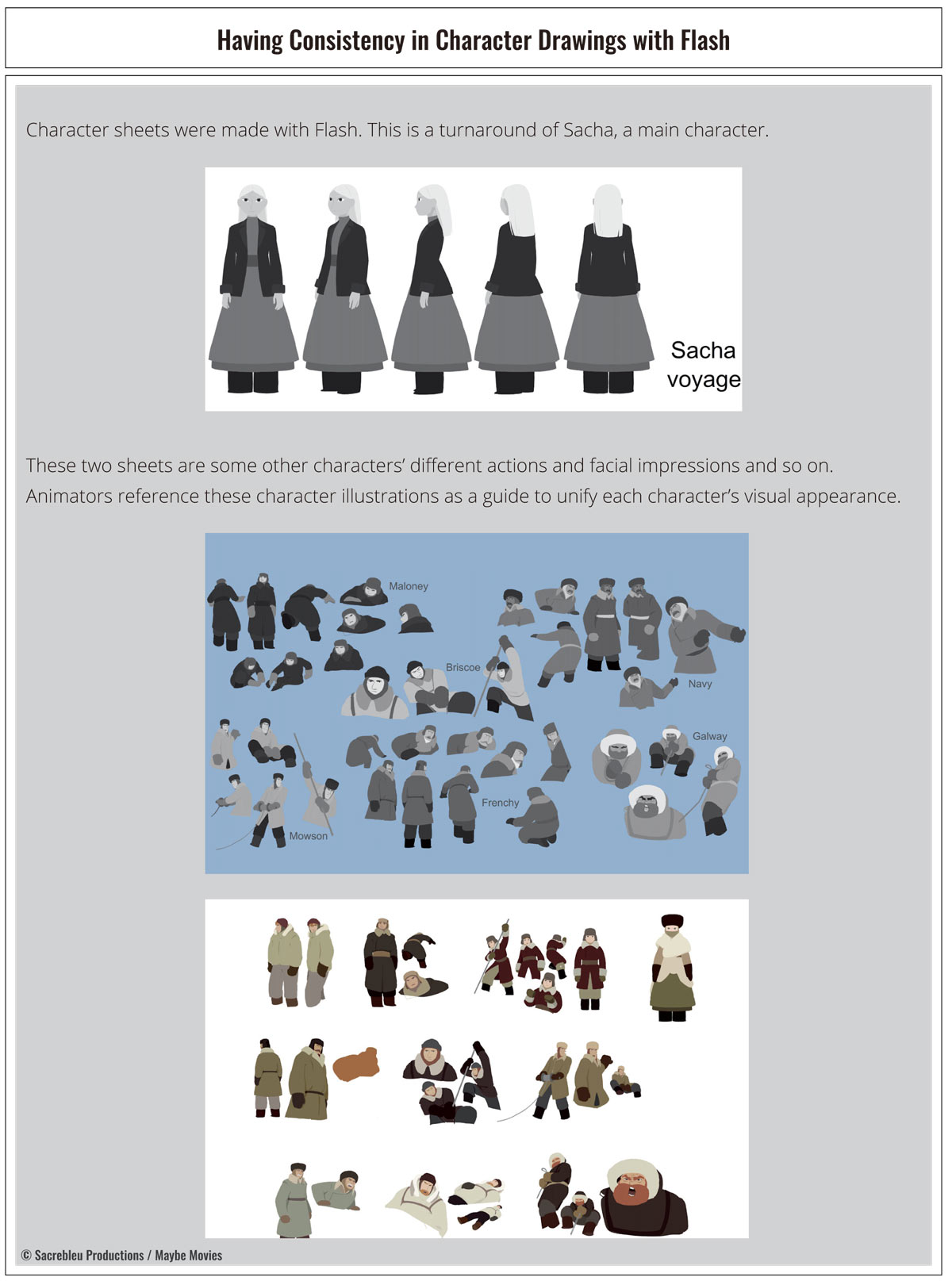

Chayé says that it is a long process to reach the final character designs from the start of the project in 2005. Some basic character design ideas such as not having outline and a nose with some graphic lines were out there, but the design evolved along the way.

Taking Sasha as an example, Chayé says that he has a lot of influences from his previous works that he was involved with. “It was more instinctive. I went to work as an assistant director to Brendan and The Secret of Kells, and I was influenced by the work of Tomm Moore. It started to evolve a little bit to simple shapes and to working with graphic shapes. Then, I went back to work as assistant director for Le Tableau. That also gave me some influence. At one point, I started to outline the characters, and my friends said to me, ‘oh, that’s really nice!’ I felt that it was interesting and I had to push in that direction. I’ve been developing this technique in parallel, while I was an assistant director”.

The Importance of a Production Pipeline

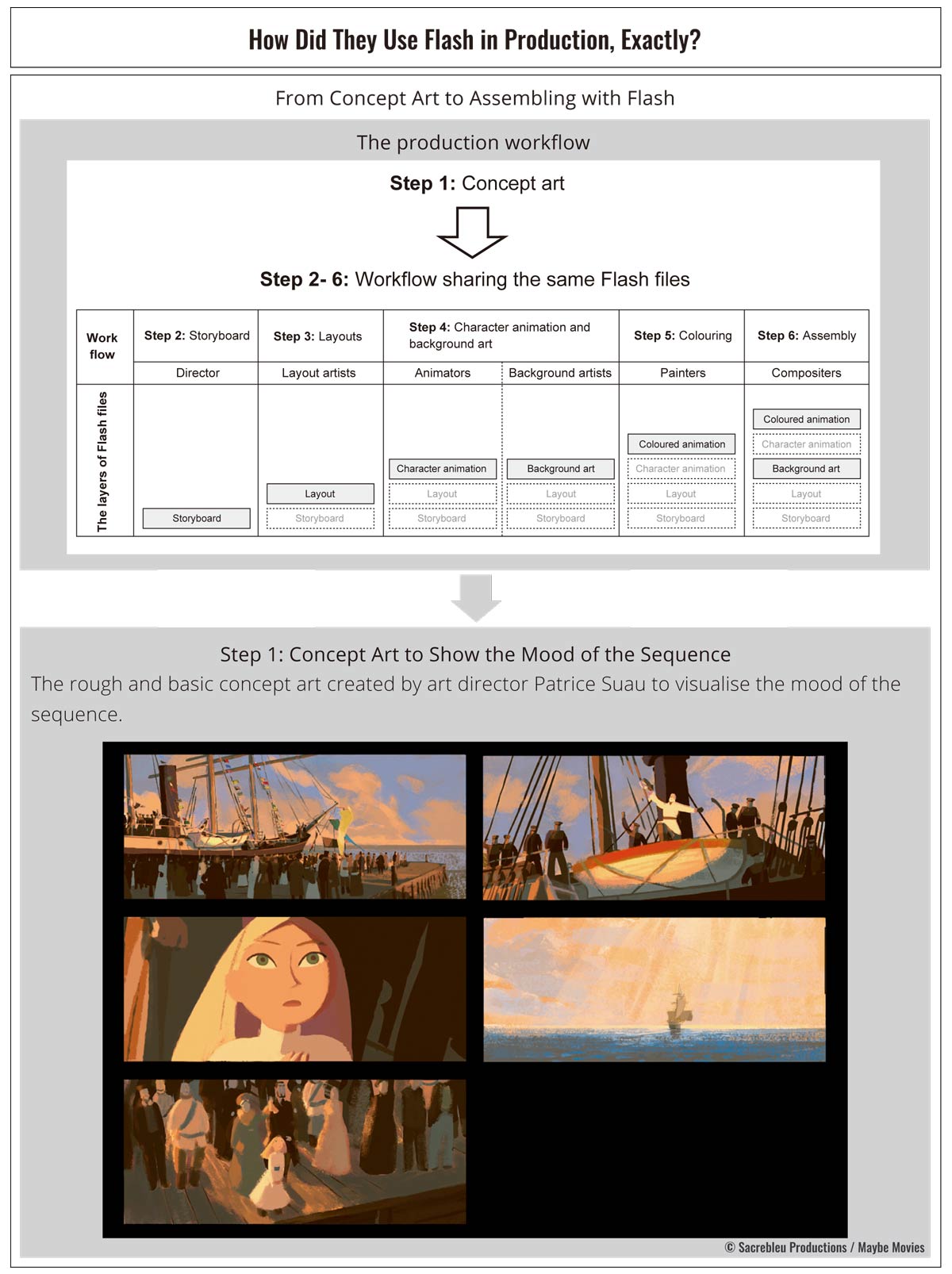

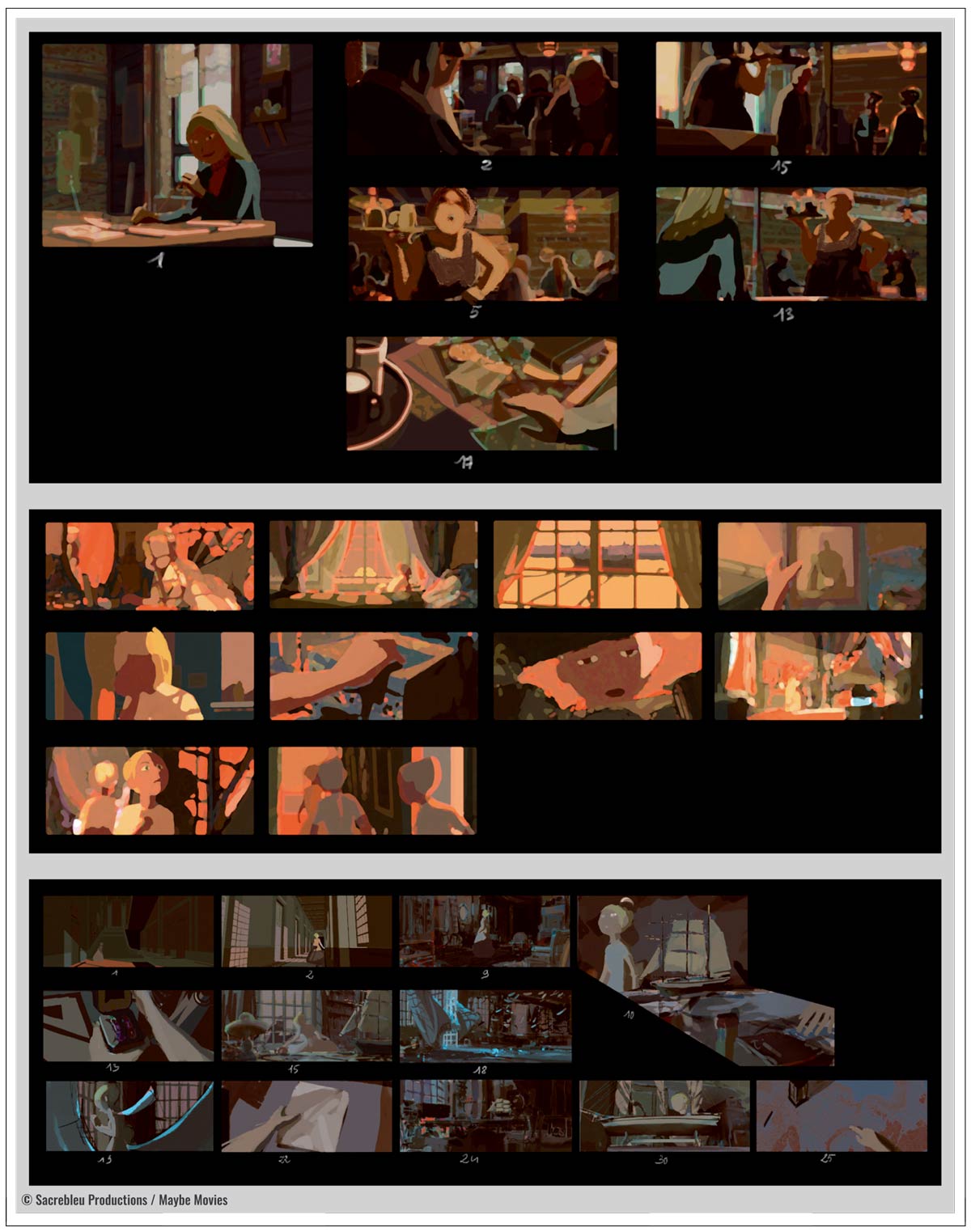

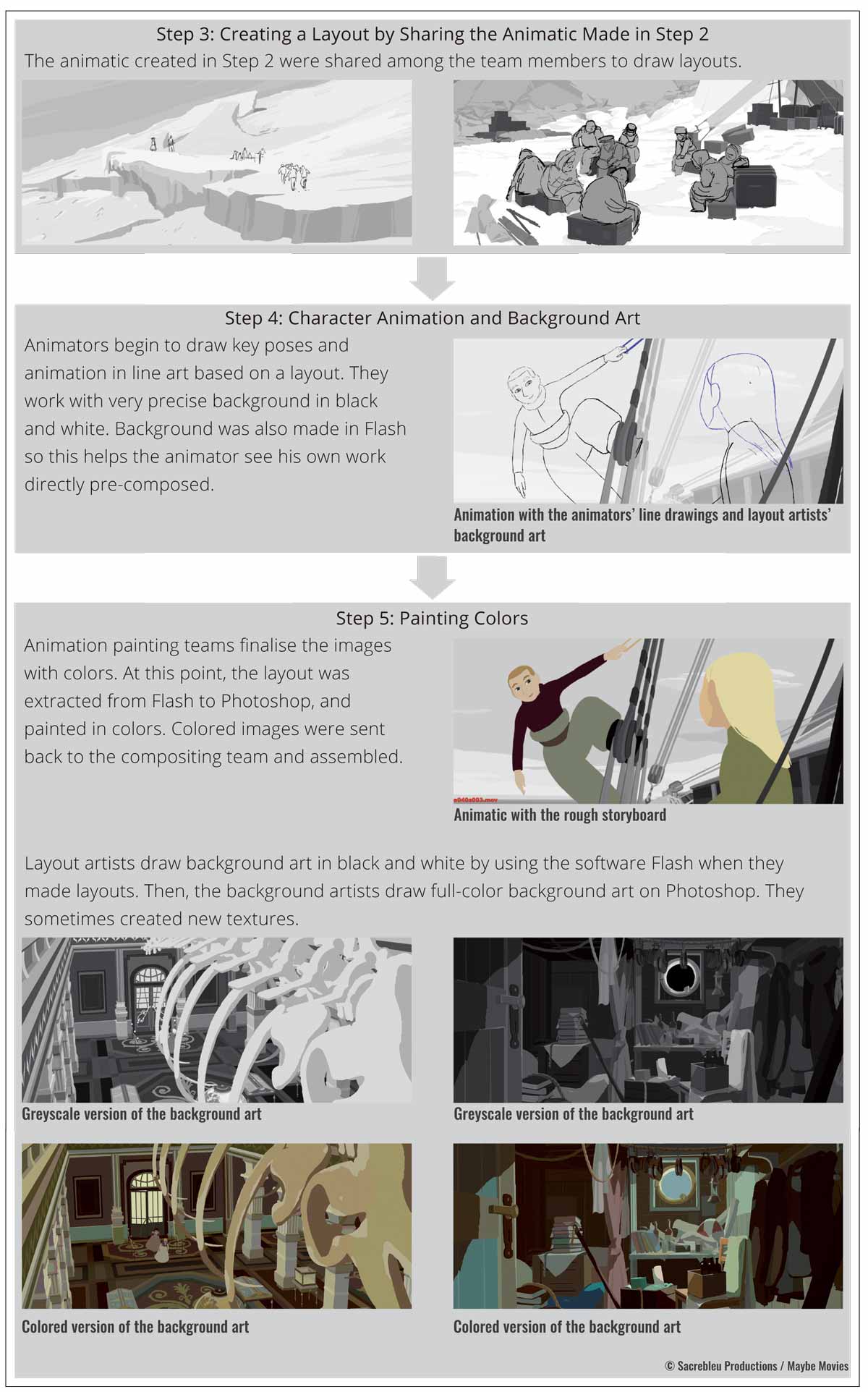

While Chayé was working on different projects, he started realising the importance of the production pipeline. He invented a pipeline to complete the work with Flash. He used Flash for the storyboard, layout, animation, and coloring. The only part where they did not use Flash is for coloring backgrounds, which are done with Photoshop, and compositing in After Effects.

Han places importance on Flash by saying that Flash saved them not only time but helped them make a film more economical. “It was a very important software for us, because the movie didn’t have a big budget, and to draw animation drawings like Long Way North without outlines, it takes a lot of time, because it’s almost like painting the character. We had to find solutions to be more economical, and Flash helped us a lot in order to respect the budget.”

The Important Role of a Supervisor

A supervisor is a core of the film’s production process to maintain the overall quality. Their role requires a lot of different responsibilities. Han says that it is very important as a supervisor to interpret what the director wants in terms of the mood, and check every scene, including small details, whether it follows the director’s intentions before showing the director. The supervisor serves as the first wall between animators and the director.

Chayé says that Han contributed to the film more than that by describing him as “the guardian of the character”. Han had sensitivity and paid attention to every single detail to make sure that it is the right movement for the characters. Chayé explains, “Liane-Cho knows how the character will act, how they will move. It’s a very intuitive and very sensitive way of ‘is it him, is it not him?’ and ‘is it her, is it not her?’ For example, he animated the character adjusting her own hair. Is it too girly or not too girly? You will find the balance for the character. He knew her very well because he had access to the whole story. He knew from where she went and to where she was going. He was in charge of controlling every gesture, every acting of every character that will fit in the progression of the character, in the character itself.”

Han adds, “My role is actually to ensure homogeneity. Because of the budget, I have to find a way to make things economical. I have to communicate it to the team as well. In this movie, it was quite special because I was supervising the posing, the animation, and the animation drawings themselves. I could sometimes control the whole process, and sometimes I could anticipate the problem that would happen on the next stage, and try to make the right corrections on things. I sometimes had to correct the animation, but directly in the clean-up. This is because I had this overview of everything. I was also doing storyboards so I know that the mood and the expression have to be like that. For example, in moments Sacha has to communicate this emotion. After that I showed to Rémi for approval and Rémi gave some corrections and he communicates with the team. It was more or less functioning like that.”

Sharing Emotions

Both Chayé and Han say that it is all about the emotions in the storytelling, and that is what they cared about the most. They made sure that the characters communicated the right emotions to the audience. To achieve this, Han says that he talked with the team a lot. “I was listening to their ideas if they had suggestions, and we had briefings with Henri (producer), and try to find the ideas.” He continues, “We couldn’t fail in the emotions of the storytelling. It had to be the right storytelling, emotion, and rhythm, and that’s the most important. Some animation geeks care about the drawings, but the average audience are more focused on the emotions of storytelling and rhythm, rather than ‘her eyes are not exactly on model’ or whatever. We focused more on what’s important for the audience.”

Han recalls his conversation with Toshiyuki Inoue, one of the juries at the Tokyo Animation Award held in March 2016 and a well-respected animator in Japan, and Inoue’s comment shows what they tried to achieve was successful. Inoue asked Han, “How could you have so much consistency in the movie? There is no off moment or whatever”. Han says, “Firstly, there are off moments but it’s just that he didn’t see it (laughs). It is because he is in the movie. I think it’s because we tried so hard to make the emotion and rhythm right, that he forgets about the off moments… He was more into the flow of the movie.”

Han points out that simplified characters makes it harder to keep consistency. “Simple doesn’t mean easy to draw, actually. Being simplified means that it is also even harder because you have to make it very right. Toshiyuki Inoue was very impressed and said that he often had to correct. In my case, I worked hard on the acting and the performance, and people who are watching the movie could forget about the small technical issues. They were just into the movie and I think that is a very good and unique feature. I was very honoured by the comment by Toshiyuki Inoue and it was a great complement from him.”

Emotions vs. Actions

In Long Way North, the actions of the characters and background scenes matches the story. Han explains that it is because of the storytelling. “I think it’s really the storyboard that creates the action for us. The storyboard tells us things such as how you place the camera and how the character will appear on camera, all these kind of things. It was more about creating a dynamic, and not the animation itself.” Chayé agrees with Han that it was probably more about storytelling than impressive animation.

To deal with the difficulty in animating action scenes, they had a scale of one to four determining the level of difficulty in animating each scene. For them, emotional scenes were given higher points in terms of difficulty. Chayé explains, “We had different levels of difficulty for each scene and we were deciding with Han the level of each scene. For us, if it’s somebody running or somebody doing an action scene, it would be a one or two, the lowest level of difficulty. For example, at the end of the movie when Katch is looking at the horizon and sees that the boat is not here and everything. Suddenly he is panicked, and he looks at Sacha with full of fear and disappointment (Picture 9). This scene had the highest difficulty level, like four. We wanted the emotions to be exact and to be right. That was the way we deal with scenes of varying difficulties. Action versus emotion, and the rhythm of the movie was what we tried to make tense and to stretch it as much as possible. We wanted people to be inside the story.”

Chayé recalls his conversation with one of the animators on complex staging to make it better and he believes that input from the animator is indispensable. “Remember, some very good animators give a lot of good input for staging. For example, we had intricate scenes with a lot of characters. There is a wreckage in the icepack, and the whole crew of 12 people were there. I remember that Nicola, who worked with Liane-Cho on the whole sequence, had a lot of input because the storyboard was unclear. We had a lot of problems in editing it, there were dialogues that had to be redefined at the very last minute. The whole thing was a little bit fragile and the animator worked mainly on staging and it was a really, really nice input.”

Building a Talented Team, Bounded with a Great Story

A creative team is essential for a successful project. We asked how they could gather talent for the best team. Both Chayé and Han say that it is networking. They also work on different film projects, and this helps them build a network of talent. Chayé says, “In the beginning I knew several people, and after that, I knew mainly the others that people brought in. Liane-Cho brought in a lot of people he knew. I didn’t know them at first. For example, Liane-Cho advised me to go to him for the color artist, that sort of thing.”

Han adds, “The more people you hire, they also have connections and they can introduce some other talent, it’s really like that. I mean we all work in different studios, we meet together again and make friends. I was in Gobelins, so I know my classmates and I also know a class above or under me or so at the same time. We know each other. After work we would just have some drinks and get drunk together, and make friends. And then, we know ‘Okay, this is a friend. I know I can trust him and I should show him my project’.”

Chayé compares his creative team as to a crew on a boat. “Very often, I make a comparison with the sailors who go for like six months on a boat. They have to go through storms, bad weather and that sort of thing. They have to live together for a while. You need to have some people that you know will react well if there is a storm. It’s very important that they need to be dynamic and good. They need to know how to work in a team.”

Han says that it is very hard to have the right people, and they were lucky to have a great team for Long Way North. “We had the right people most of the time. People were really motivated, enjoyed the project, and liked to work on it. That’s why they gave a lot of themselves and got involved. The good thing with Long Way North is that they wanted to show off their talents. They worked for themselves. They knew that there was a financial issue but still agreed to do their best because they really enjoyed and committed to the project. They did not think about themselves. They thought about the movie. ‘We wanted to work on this great movie, and make it as great as possible’.”

Henri Magalon, one of the producers for Long Way North, describes his role to bring the right people on board. “It’s also a love for Rémi’s personality. I think that he’s quite generous with everybody. Among the producers, we had a good talk about what we needed to do. We were very open-minded. My personal involvement with the film started in the middle of the project. I spent three years with Rémi. My main goal in life, and in this movie in particular, was to have a great story. With the right story, everybody knows why we are here and what we have to say in the film. That really bonds people together. When the story is not perfect, that’s when the team goes wild and no-one knows why we do this and the character does that.”

Han agrees that sometimes a director could be distant from the rest of the team. For Long Way North, Chayé was close. “Most of the time, the whole team were having lunch all together with the director Rémi and talking. There was a huge connection between the team and the director. It helps so much in the relationship. When the team respects and loves the director, they all work together to help him and the movie.”

Magalon continues, “Rémi was not afraid to meet people and to talk. Some directors hide themselves in their office while they try to figure out what they are trying to do. Regarding this point, Rémi was really generous and willing to talk. He knew what he didn’t want and what he wanted. That was one of the great things we had. We had a limited budget, so we had to rent an open space. This actually turned out well. It was a good way of seeing that Rémi was there with the team and very accessible. People didn’t want to disturb him because he was talking to each one of them all the time, and it’s great chemistry for the team.”

Music

Music plays an important role in the animation. It communicates the right emotions through music. Chayé decided to work with Jonathan Morali, who is the singer and composer for a French pop music group named Syd Matters.

“Very often, for a one-and-a-half-hour movie, you generally have something like one-hour-and-ten-minute music. For us it’s 25 minutes of music only. It’s a very short amount of music in the movie. The music is given really musical sequences with a clip of running or travelling, that sort of thing. We have very little music because it’s a movie based in Russia during the 19th Century. I didn’t want to have something similar to 19th Century music, Russian music, that sort of thing. I wanted to have contemporary pop music to give a feeling of modernity in the movie.”

“Basically, it’s very simple to work with Jonathan. I gave him the animatic. Very often we already have music by Syd Matters in the animatic. It was a good tip for him. Sometimes he will do very simple music with his own instruments, and after that he will ask musicians to do the complementary music. It’s really, really easy to work with him, definitely. The song design was very important, too. We had a big element of song design. The song design team had a huge amount of work, and they had to recreate a lot more, the boats, the storm, and the icepack. It was a lot of ambience, and they did very nice work.”

Difficult and Fun Parts

We asked what was the most difficult and enjoyable part throughout the journey to Chayé and Han.

Chayé recalls, “For me, the most difficult part was building a story that would work. The worst moment for me was when I met Henri (laughs). Actually, it’s true because I was really down. The story was not working. We met Henri and he presented us some script doctors, discussing about the reasons why the story was not working. That was difficult for me, because I had spent already eight years on the story and the story was nearly collapsing at that point.”

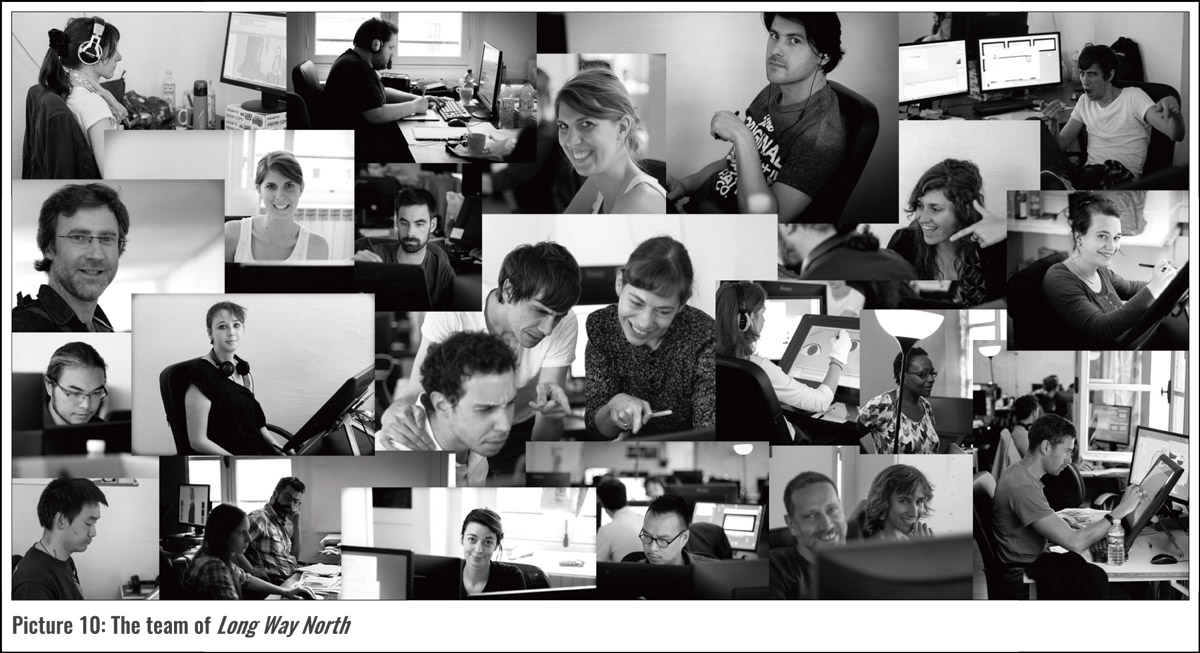

He moves on to the moment he enjoyed most by showing photographs of the team (Picture 10).

“The best moment was probably what you can see here, when it was in the studio. I have some very nice photographs here made by one of our animators. That was the team. Stefan, the graphics supervisor, the artists team, and animators. For me, that was the best moment, when everyone is working together. It was a really good ambience, very nice people, very focused and very dedicated to the work. Very easy to work with. I remember the summer. That summer was especially really nice. The doors were open, and we were having parties at the studio and had a really good time. That was really cool.”

Han says that his most enjoyable moment was also his worst moment at the same time.

“It’s funny, because I have to explain that it was so enjoyable to work with this project and all the people there. It was also so difficult because it caused us so much work, pressure, and things to do. This is why it’s funny because when I stopped work I said ‘Never again, it was too much!’ But right now I’m actually ready to work again on Rémi’s next project! It’s the funniest thing. I would say my whole production was the most enjoyable moment and also the most painful.”

For Han, the difficulty added up when he had to supervise three different teams, for three months, at the same time. The biggest team was under his supervision. There were animators, assistant animators (they call them ‘animation drawers’), and the Danish team under him. “It was crazy and difficult but at the same time it was less stressful when everything was flowing great”.

Trips for Screening the Film

USA

After the film completed, they had trips to screen their film in various places. At one point, they made it to the USA and visited Pixar, and LAIKA in Portland, Oregon. They were, first of all, amazed with the size of the studios. They say that their entire movie had about 180 people at the end credits and their studio is about 40 people which is much smaller compared to the size of studios with 2,000 to 4,000 people. They were also astonished and impressed with the environment that American studios had, such as pools, gym rooms and screening rooms.

Chayé describes his experience, “For me it was like ‘bah!’ It’s very strange because I’m used to the size of European animation studios. I’ve been working in it for 20 years, and I only know that sort of size of building, which is very friendly, and very easy. For me it was very, very strange to go there. Especially Pixar. The studio in Portland is more human-sized.”

Chayé was impressed with the stop motion facility at LAIKA. They had a chance to have a sneak peek of Kubo and the Two String and were amazed with the beautiful art and craft.

Han says, “I would say the same as Rémi when I saw the studios. I stayed two weeks so I could visit Disney, Dreamworks and Paramount. When I visited Dreamworks, it’s crazy, it’s almost like a resort. It’s like a city that you go to during your vacation or holidays. You see what I mean? You see all this food out for free, it’s just ‘wow’, it’s paradise. But at the same time, it’s too huge. When I see this kind of thing, it’s too much. Of course, I really like it when we stay, almost like a family team. There’s so many people, and when they work on a project, they’re just a little piece of it. Most of the time, they have been thrown out because sometimes, projects have to be cancelled. Sometimes they have to re-write or whatever. It was very attractive at the beginning, and I said ‘oh, I will spend three months there, for fun‘ but then of course, for me, I wouldn’t be happy, personally, to be in this studio.”

Han recalls his experience of screening Long Way North at Pixar, Dreamworks and LAIKA as amazing and very positive. They showed their film to Pete Docter and Ronnie del Carmen, the directors of Inside Out, and received very positive feedback. It was the same in Dreamworks, and they had a great opportunity to talk with the creators and famous animators there. At LAIKA, they had a chance to show the film to the director of The Boxtrolls. They talked with him as well, and his impression was very positive.

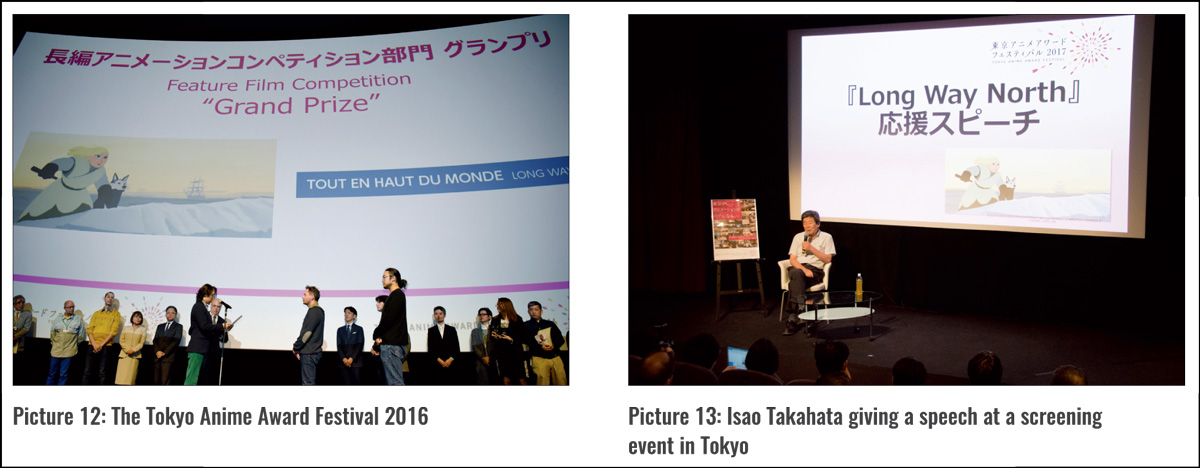

Japan

Han says that the impression they received for the film in Japan was similar to the ones in the USA, although the USA and Japan have a different culture. He had a chance to talk with Ryuichi Yagi, one of the juries at The Tokyo Anime Award Festival 2016 held in late March 2016 in Japan when they won the Competition Grand Prize. Han was very humbled and pleased with an impressive speech given by Yagi during the award ceremony and his impression of the film was very positive. He also enjoyed talking with Japanese animators and directors including Isao Takahata, the director of Grave of the Fireflies, and Toshiyuki Inoue who got him into the animation industry.

After the award ceremony, Han had a chance to visit Production I.G in Tokyo. He was stunned by a huge map of Tokyo, indicating different locations with a lot of pins. All the pins show addresses of all the freelance animators that they are working with. “It was crazy to see every address on the map, and in the main entrance of Production I.G, there is a cabinet with a pigeon hole, which has a door. A freelance animator doesn’t have to go inside the studio actually, just go to the entrance, open the door, take the scene, put something back, close, and go home. It’s just ‘wow!’ There are also all the notes from the animation director and things like that. It’s such a huge organisation, it was crazy”.

There was also a screening event of Long Way North as the award winning film at The Tokyo Anime Award Festival 2016 on 28th July in Tokyo. The director Isao Takahata appeared as a guest speaker and made a speech. He mentioned that he hopes that the Japanese animation industry will make more animations like Long Way North with a message that would mean more to your life than just entertainment, although he does not watch recent Japanese animations, so a lot of his words should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Impressions of the Film Around the World

Long Way North has been shown around the globe. Han thinks that the impressions of the film from professionals are all quite similar. “I think they all liked it. Even if they don’t like the story, they at least liked the graphics, the imagery. Even if they don’t like the graphics, the imagery, they liked the story. Basically, they all liked it”. He is also happy to see that a general audience enjoys their film. He saw a Vlog of two kids being interviewed for a magazine at TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival), and those kids had enjoyed seeing the film. “The film is quite universal, which is very nice and unique. It’s for all audiences to enjoy more, not only for kids but also for a lot of adults”.

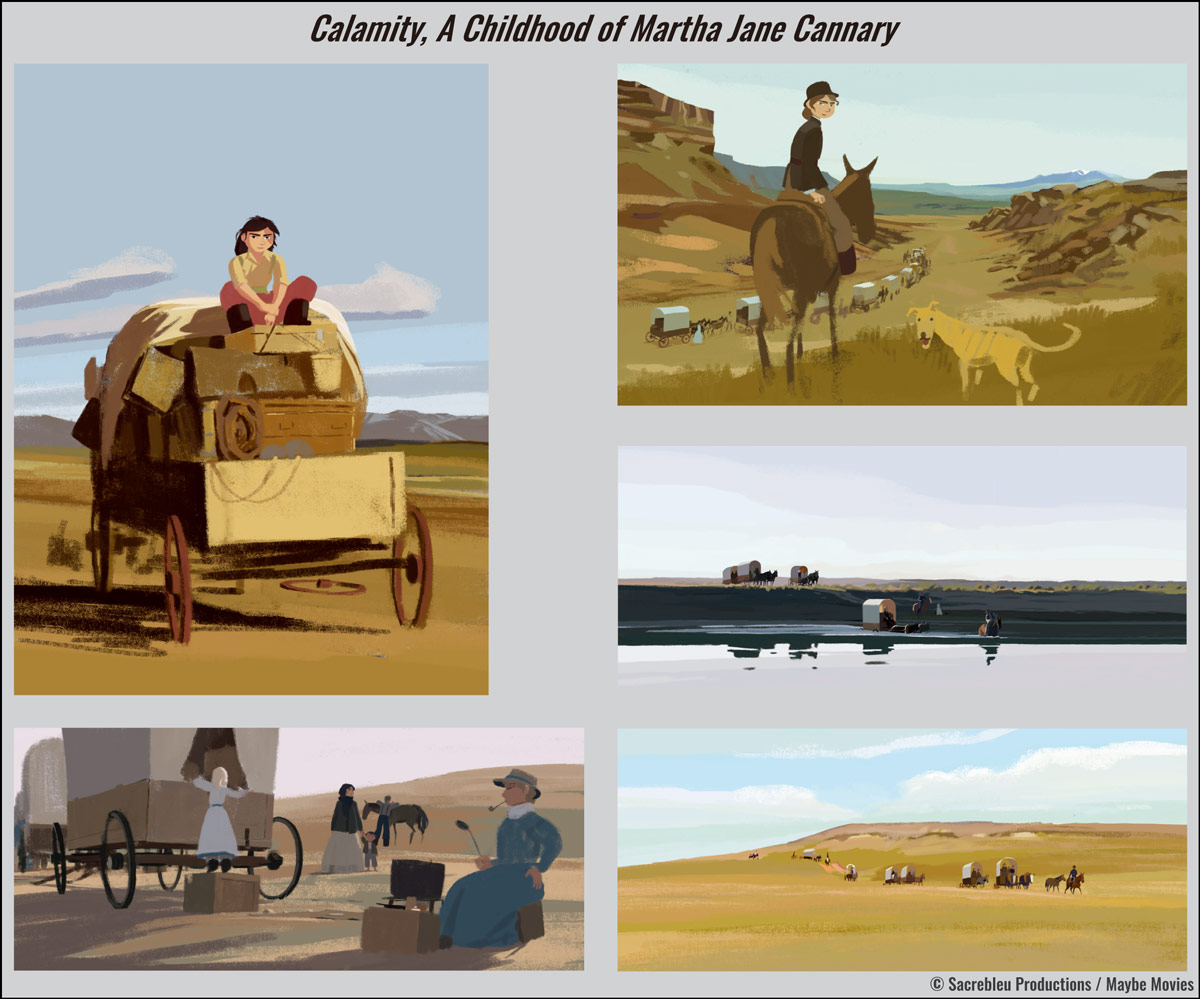

New Project: Calamity, A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary

Chayé and Han started working on a new project titled Calamity, A Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary. Chayé explains, “It’s a story about a girl that will grow up to be Calamity Jane. Calamity Jane is a very famous American character. She was dressed with men’s clothing, and went to saloons to drink with men, where it was forbidden for all women. She was a real cowboy, knew how to ride horses, and how to herd cattle. It’s very famous in France and in the USA. We’re going to do the childhood of her, when she was in a wagon trail. It’s with wheels and horses, and you have several wagons one after the other going to Oregon, to the west. She’s a pioneer. The idea is to show how she invents her own character. Based on that, she was just a normal girl like the others, but suddenly her father is injured. She had to ride and she had to take care of her siblings, that’s the idea. It’s a very nice story and character. We are actually writing the story now with the same scriptwriter from the Long Way North focus team Fabrice de Costil.”

Chayé develops the story further in a way described by the French term “dispositif” that is used by French philosopher Michel Foucault. “It’s nearly like a machinery for a scenery or device. It means that we need Martha Jane to be ashamed. It is not by just creating one or two sequences, but to build a system that will make her ashamed.”

Chayé also gets together with others to talk about devices, targets and objectives. “Like we need her to be in that state at that moment and we need to build something. I know that when I talk with Liane-Cho, he will have plenty of different ideas and invent plenty of different things to push. It’s all for Martha Jane Canary, we want to talk about her story in a way that she does. She is a girl, but would put on trousers and act like a boy. She would not be accepted for that. We want to question that problem, why a girl with trousers, why was she not accepted? Was she a girl, was she a boy? Why people are reacting so strongly to that? That’s the reason why we have some state to go through with her. We have to invent some situation, where it’s funny and when it’s sad. At one point she will cut her hair, because if she goes for a fight with a young boy, the boy can just grab her by the hair and pull her into the mud and win the fight. She goes back to her wagon to cut her hair very quickly, then she goes back to the fight and wins it. After that device, at one point we have an idea, and suddenly we can write dialogues and situations just appear quickly. After that we just throw it away. So it’s building, rebuilding, collapsing, rebuilding, collapsing, rebuilding, something like that.”

Regarding the team and structure for the project, Chayé and Han are clear that they want to keep the same structure as much as possible. “We are not rebuilding every time on a different pipeline and different graphic style. We’d like to build something with the same team. The idea is to make this movie with the same team and the same sort of conditions that Long Way North had, to be able to hire the same people as much as possible”, says Chayé.

Their plan is to use Flash, but improve and learn from their experience. Han says, “We try to correct all the mistakes from the past and make it better, but actually use the same base. It’s the story that makes all the movies so different. I think that’s the project we tried to do. We are very happy that we can start the project. At the beginning, Rémi wanted to be a nurse and stop animation after the movie. I hope it’s going to be a great adventure. We just hope that it won’t take 10 years to make it!” They also hope that their international success with Long Way North helps them with financing.

What it Takes to be Creative, and Messages to Emerging Artists

We asked Chayé and Han how they keep their creativity. For Chayé, it’s sketches, a lot of reading, and seeing movies.

For Han, it is a little bit of a different story. It is hard to motivate himself when he could tell that project would not be going in the right direction. He says, “For some time until Rémi starts his new movie, you have to eat, so you have to work on different other projects that are sometimes not as motivating. You still do the best you can, but it’s still very hard. The danger is when you get bitter of the business, because you know that no matter what I do, it’s going to be bad. It can kill your creativity. You become more automatic: ‘just do the recipe that I know, and that’s it’. That’s why it’s very hard to keep this motivation sometimes.”

Now, he is happy that Chayé starts his new project and thinks that refreshing yourself is important, like watching a lot of movies and living a good life. “I think Takahata said that ‘animation or cinema is how to express life, but how can you express life, if you don’t have a life yourself?’ That is why it’s very important to experience, and to live. The emotion you get from life becomes inspiration that you put into movies. That’s why it’s very important to observe and to feel.”

Their passion for drawing is the drive for them to continue animation. For Chayé, drawing is a way to interpret reality. “Simplify it to the core, and it’s the reason I like it. It’s so powerful.” Han adds, “You can cheat to communicate the emotion you want. Of course, it has to be good drawings, and also, we know how to do it. We basically started our career in 2D, and then why change to another technique? Something to learn again. But I think we also believe in the warmth of 2D animation”.

Chayé describes the attractive points of 2D animation as a direct interpretation. “It goes through your interpretation. When you deliver a drawing, and you deliver something that you have seen, and that you go only through the eyes of the character, and the impressions. It’s not the machine that creates it. I used to do 3D animation, but you can have the power of painting with 2D. You are able to put emotion into the sky, and you will feel the emotion through the way it’s painted. You have the tools of the painting and you have the tools of the cinema”.

Han uses examples from Long Way North to elaborate what they mean. “When you see the background or character, there’s such a simplicity in the shapes. So simple, but at the same time, it says a lot. I don’t know if it would be that easy to do that in 3D, for example, to have such a simple character, and a simple background. It would take so much time to put the warmth of 2D into a 3D process. With 2D, you just have to draw and paint, and that’s it. I guess it’s less complicated”.

Han also warns of the recent trend of people saying 2D animation is old-fashioned. He thinks it is more to do with the marketing. The general public are more exposed to 3D animation than 2D animation, due to the way 3D animation is marketed. This does not mean that people do not like 2D animation. It is a matter of communication.

Lastly, we asked them whether they could give some messages to young and emerging artists for their careers.

Chayé says, “Make your own movie, that’s an advice Jean-Christophe Villard gave to me. I was a technician at that moment, I was a layout artist on a TV special called The Poisoned Gift, and he was a background artist. He is such a nice animation artist. He came to me and said, ‘stop working for them, stop working for those movies. Do your own movie now!’”

Han leaves a message, “I would say that animation, like every artistic technique or craft, takes a lot of time. It takes a lot of time and a lot of work to do. Also, it’s not only about drawing, but it’s also how to feel and to observe. Some people are so focused on technique, which I can understand, but I think it’s very important to understand that the reason we are doing this job is for an audience. It’s very important that we have ideas. Always try to find ideas and the right way to create emotion. For students, I know that we want to impress our friends, and other students, to be the best animator, the best of all. At certain points, it’s very important not only to focus on that, but also how to communicate emotion to move the people. That’s something that students shouldn’t forget. If you’re too focused on technique, then that’s a colder artist and a cold technician. I think it’s very important, as Rémi said, to do your movies or tell stories, but also do your job in a way of creating emotion, which is laugh or cry or whatever. Just aim towards the audience. And finally, practice, a lot of practice”.