In Japanese animation, background art is essential in constructing the foundations of the world of animation and to depict the feelings of characters at certain times. We talked with Yusuke Takeda, who contributed to the art of various projects, starting from Patlabor: The Movie (1989), BLOOD THE LAST VAMPIRE (2000), and Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (2002), to recent work which includes Eden of the East (2009), Sword Art Online (2012), and The Eccentric Family (2013), with his excellent skills in drawing and expression. He shares, behind the scenes, the background art, the current situation of digital production, and the attractiveness of his work.

The Foundation of Bamboo Studio

Could you please tell us how did you decide to become a professional background animation artist?

I loved drawing since my childhood. At that time, the only one Manga title that we have at home was Cyborg 009 in my father’s shelf. This is the first Manga that I took in my hand. Since reading it, I started collecting Manga by myself. It made me start thinking vaguely: “I want to have a job in drawing the visuals!” The only choice as a profession was animation. At first, I wanted to be an animator, not a background artist, and thus I went to school related to animation. But, I had a strong feeling that I wanted to draw using a brush, with color, rather than a line, so then I aspired to background art in animation.

I started my career at a studio called “Mechaman” in Kokubunji, Tokyo. There, I learned how to draw on paper with paints, starting from the basics. Mechaman was the background art studio, which took part in projects such as Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). After a while, I became a freelance background artist. About a year after I became a freelancer, I had the privilege to work for Patlabor: The Movie (1989), directed by Mamoru Oshii. I think it was about when I was 19 years old. Through the project of Patlabor: The Movie, I got along with two very talented background artists, Norihiro Hiraki and Tatsuya Kushida, who are close in the same generation as me. We naturally said things to each other like: “Let’s work together for the next project”, and “If we work together, then shall we establish our own studio?”, then we decided to found a background art studio named “Bihou”.

I think it was around the year of 1998, which is about 5 years since the foundation of Bihou, when I experienced the transition from analog production to digital production in Japanese animation. After that, I left Bihou and started my own personal studio called “Bamboo”. We had a really big project, which was Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex – Solid State Society (2006) at that time, and decided to take that project with some colleagues from my time at Bihou. Then, we could say, “It seems like we can continue as a business” and “Let’s make it work as a studio”. Then, we incorporated it as Bamboo Inc.

The Transition to Digital Production

Did you aim to specialize in the digital production of background art when you established the studio, Bamboo Inc.?

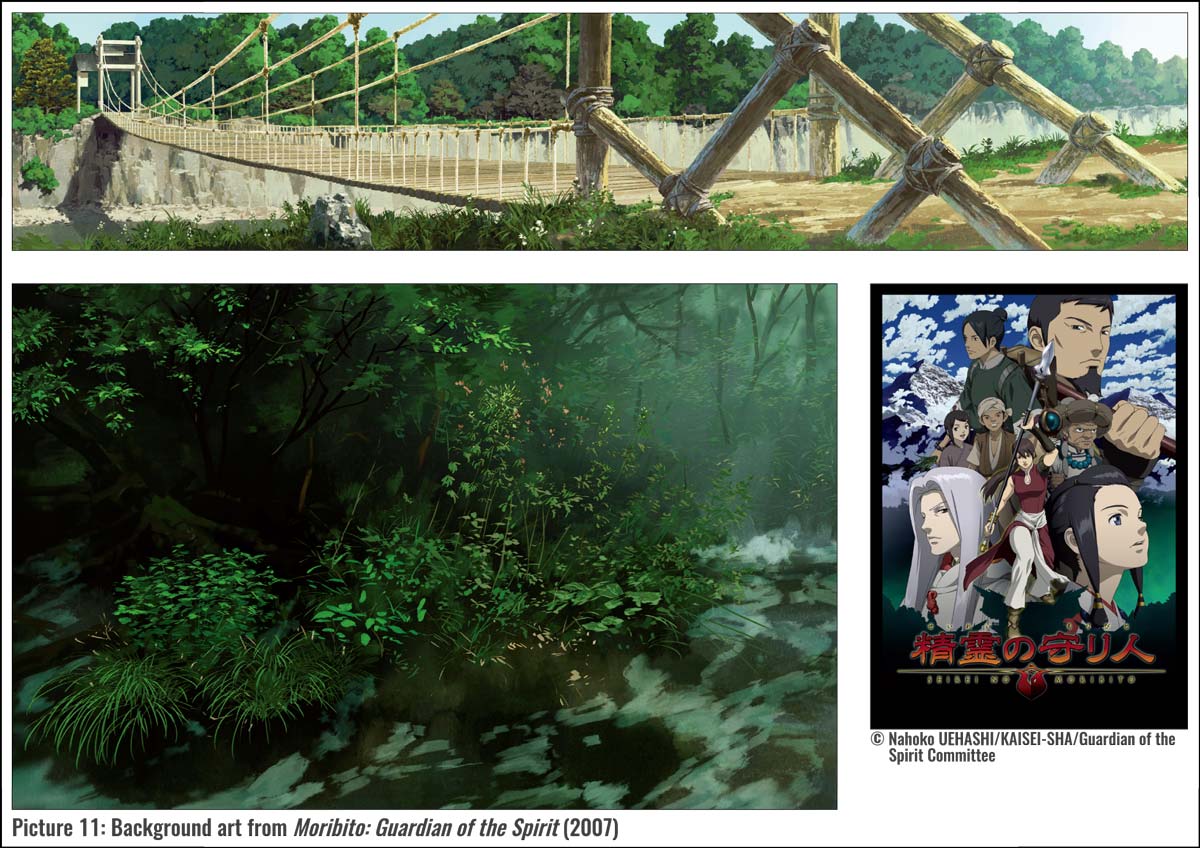

There was no aim to focus on digital production, but more of an animation project to work on as a precondition to establish our studio. While getting involved in each project, we were gradually introduced to digital production. We fully moved to digital production from 2006 when we worked on Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit (2007). The production process during the transition time was a hybrid. We first drew background art with watercolor on paper, next we scan them in to create digital data, and then we processed them with Photoshop.

Could you please tell us the projects that you have special personal attachments in, among the many projects that you took part in?

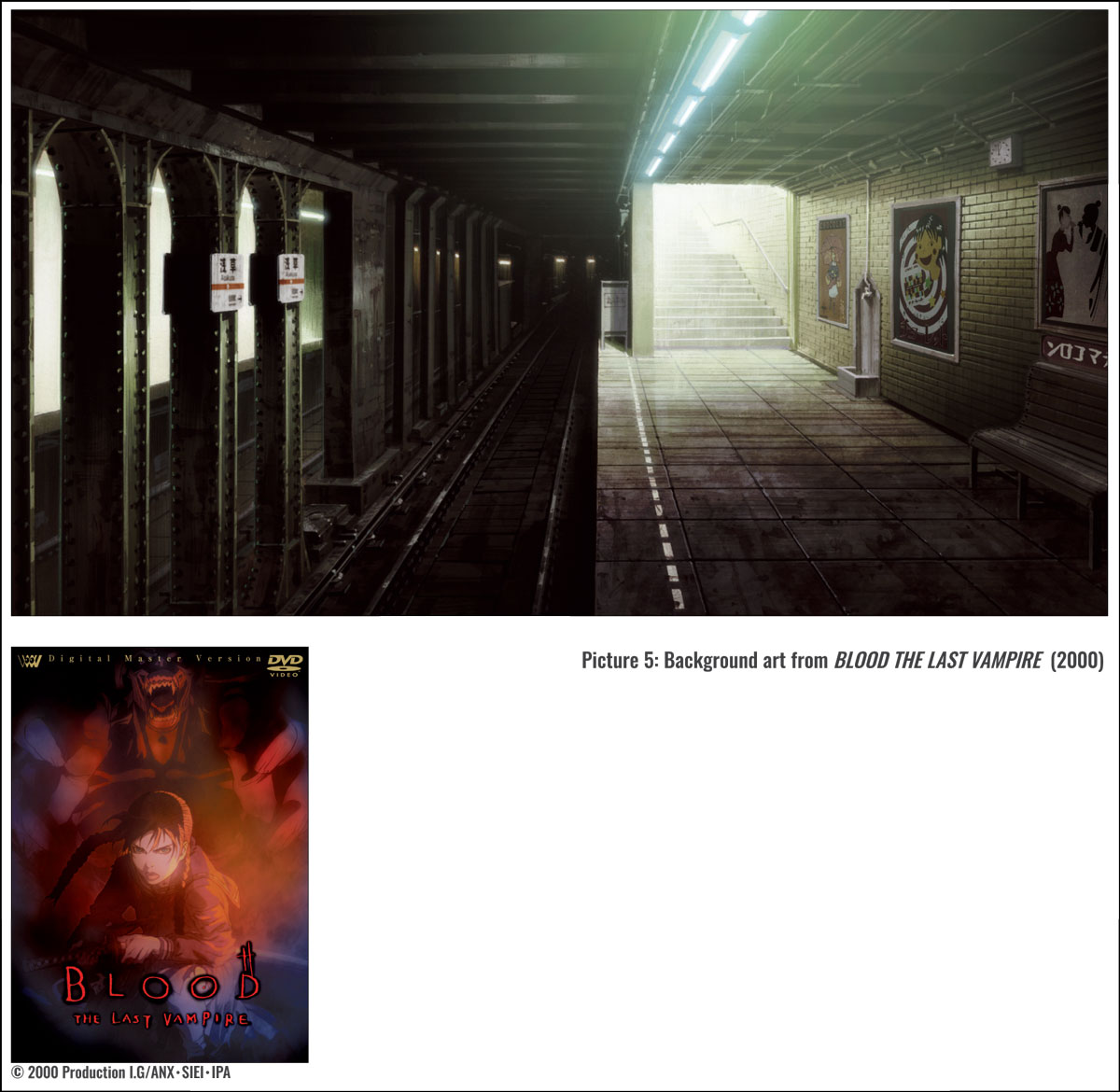

Each project has a lot of memories with me, but I would say BLOOD THE LAST VAMPIRE (2000). It is a 60 mins film directed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo. I think this is the first animated feature film for theatrical release that we challenged in full digital production. It was a very valuable and impressive experience.

It was still the time when we did not have any know-how on digital production. For example, when we scanned background art, we could not display them on monitors with the color accuracy that we wanted, so we had to adjust the color cut one-by-one. It was so much during the predawn of digital production that we had a variety of issues such as finding the correct settings of scanners and monitors needed. Still, in such a time, we didn’t know what kinds of technical problems and troubles could occur when we started the project, which we had the courage to produce one feature film. I was lucky to be able to work for the project.

There were some staff who had great experience in advanced digital production for visuals, so that we could have a thorough trial-and-error experience by learning a variety of things from them. The digital production skills I gained from that experience consists of the basics of my digital production of background art. I can say that thanks to the know-how, which I gained from that one project, I can still do my business. It is already something like 18 years ago.

Digital Production

Do you draw the background art digitally for every project that you take part in and are the character animation (layouts, key frames and in-betweens) for the projects drawn on paper?

Animation is often still drawn on paper in Japan. In-betweens drawn on paper are scanned and made into digital cels, then it is common to superimpose with digitally drawn background art via After Effects. Before then, there were several software to support animation production. I think that the first software is a British one called “Animo” (a software by Cambridge Animation Systems). In the beginning, when After Effects was introduced, we used After Effects only for special cuts and use simple compositing tools for all other cuts. But I think almost everything is done by After Effects nowadays.

What kind of difficulties and challenges did your studio have through the transition from analog production to digital production?

In the early days when we introduced digital production, it was difficult to recreate natural objects. So we used to keep the ratio of analog drawing and digital drawing to be something like 6:4.

For example, one of the difficult expressions to be drawn in digital is subtle blurring, which we used to express by using a brush technique and paint bleed in analog, for drawing things such as clouds, to allow them to have softness and emotion.

It was difficult to replicate this analog blurring effect by adjusting the settings of brushes with Photoshop at that time.

When we participated in the TV animation series Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit, we noticed that we can make a similar expression by the combination of some tools of the latest version of Photoshop and Corel Painter at that time. So, we said, “Let’s try the whole project this way”, and this became the opportunity to move completely to digital production. This means that overcoming the difficulty of drawing natural objects as intended was the biggest obstacle in moving to digital production 100%.

On the other hand, we could draw solid things well and emotionally with Photoshop from the beginning of our challenge in drawing digitally. It actually requires a lot of skill to draw gradation evenly with poster color and brush on paper. So, for objects, which have a smooth surface, it is easier to draw with Photoshop than paper.

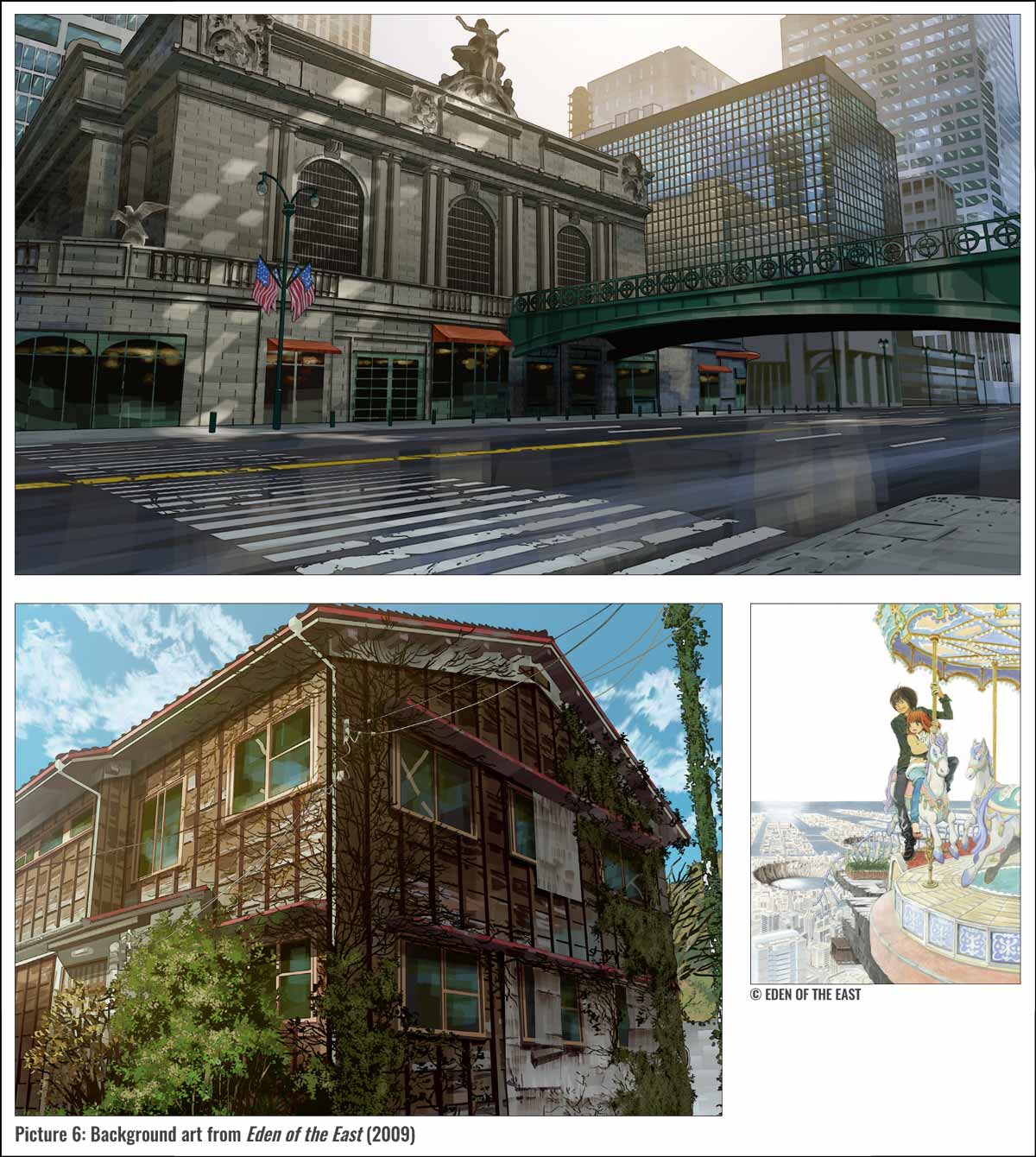

The background art of Eden of the East (2009) gave me a strong impression and a new feeling, which is different from analog drawing, because they had the sharpness thanks to digital drawing and were integrated with a texture using a wide brush and well-balanced noise. How did you establish that unique style of drawing with what kind of intention and process?

In fact, there is an animation series that became a basis of the drawing style of background art for Eden of the East. It is a TV animation series with 13 episodes titled 009-1 (2006). It had a concept of an American comic-like feel, and we were able to gain our know-how, which leads to the style in Eden of the East.

I talked with the director Kenji Kamiyama when Eden of the East came up, “What kind of drawings shall we have next?” as we had a so-called realistic style of drawing for the TV animation series Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex and Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit.

It was decided that Chika Umino, a comic artist, would be the character designer of Eden of the East. We wondered, “What kind of drawings would match the characters drawn by her?” Everyone could come up with a so-called “watercolor style” background art, which is used for animations based on girls’ comics in the Japanese animation industry. So we talked to try the totally opposite direction.

There is an illustrator whose name is Eizin Suzuki who are known by everyone in our generation in Japan. Around the time when I was a student in Junior High School, he was drawing a cover image every week for an information magazine about FM radio programs titled “FM STATION”. I personally liked those illustrations very much.

His work has very bright colors, but surprisingly realistic. He quite often drew sceneries of California in his works. He is the person who has drawn the American landscapes that we liked when we were students. And the opening scene of Eden of the East was in Washington. Then, I suggested Director Kamiyama about my idea, “How about visuals like Eizin’s illustrations?”

It could be the opposite of the watercolor style if we draw backgrounds by using an Eizin-style color tone. We couldn’t use it as background animation art for practical purposes and needed to arrange it to make it fit with the animation. But we have know-how from the American-comic style illustration used for 009-1, so we decided to give it a try with that concept.

Another reason is that there were a lot of TV animation series at the time so that we wanted to have the look of illustrations that stay in the audience’s mind to instantly understand “Oh, this is from Eden of the East!” when they changed channels on TV.

With those in my mind, the artistic style of Eden of the East came to be.

Actually, I had once tried to draw Eizin-style illustrations when I was still drawing background art with paper and paints in my 20s. It took a lot of effort to paint evenly and beautifully as well as creating outlines thinly and smoothly in black with a brush to make them looks like Eizin’s style. Then, when we were discussing about the visuals of Eden of the East, I thought that this way of expression works better with digital drawing and now is the time to realize it. So, it was the first work that can be benefited most from digital drawing, not paints.

After that, we had some work, which uses the same technique as Eden of the East. Basically the process is like being requested by a director who saw Eden of the East, “I want it like Eden of the East” or “How do we want to do it this time based on the feel of Eden of the East?”

Background Art in the Japanese Animation Industry

Could you let me know the characteristics of background art in Japanese animation and how it established?

I think one of the characteristics is the graphical realism that is different from live-action. If we look at this from the global perspective, animation can possibly be categorized into either animation for family and children, or very artistic animation. But I think Japanese animation did not fall into either category and developed in its own way.

What I am going to talk about is what I personally feel from seeing many works for a long time rather than something I studied. In the early age of Japanese animation, background art was drawn with a so-called watercolor technique. At a certain time, it was probably creators who introduced a way to create scenes and layouts from the perspective through a camera lens, which is used in live action films. This means that Japanese animation started to become more conscious about the ideas of lens, angle of view, and exposure when they create the visuals. In my personal view, since then, the visuals in Japanese animation started to have its own unique reality.

What I mean is that Japanese animation creators started to consciously layout each scenes as in, for example, this cut will be shot with a wider lens and the next cut will telephotographed. Of course, they then started caring about exposure as a next step. Although the background art of animation were painted with local color, which was called “normal” in the Japanese animation industry until that point, they started expressing the change in light and darkness depending on the environment, unlike painting everything with local color. In summary, it is essentially the concept of exposure in shooting with a camera.

I am personally thinking that the proactive challenge in making new visual expressions have been contributing to the shape of the realistic visuals of Japanese animation. Having said that, it has been 30 years since such visuals were made, so I suppose these techniques are taken for granted for a certain generation as this kind of technique is used in game and movies, not only animations.

So would it be in the 1980s, if it is more than 30 years ago?

The first time that I saw a telephotographed shot is the first scene of The Castle of Cagliostro (1979).

I see. So drawing layouts being conscious with camera lens started with animation movies and then introduced into TV series. Does this mean that this became the common feature in Japanese animation works?

Yes, I think so.

The Process of Making Background Art

What kind of things do you care about the most when you draw background art for animation? What kind of meetings would you hold with a director and layout/animation director, in terms of staging?

Background art is, first of all, based on storyboards. We discuss with the director and layout/animation director on how each scene going to be. It’s not that background art is leading something, it’s more of building it up through meetings.

For example, in the animation titled Kimi ni Todoke (2009), based on a girls comics, there was a scene in the classroom after school and we think about things such as “What kind of lights would it be, after school in the classroom?”, “The lights would probably be turned off”, “What kind of natural light would it be when the sun is close to setting?”, then we decide the basic scene setting as “The sun will set in about two hours”.

In the middle of the scene, there is one where a main character reveals her true feelings toward her loved one. So, we think about what kind of background art we would draw for that scene that expresses that well. It could be like, “Let’s change the color to meet the change in feelings, not following the natural course of daytime”, or the director may order a background with his vision and it becomes a matter of our skill on how to respond to it as a professional background artist. For some directors, they might ask, “Just a normal background”, as an order. I think that it really depends on the animation title.

The animation production workflow is not necessarily the same between Japan and the West. Could you please let us know the production process of background art in the case of Bamboo studio, briefly?

This is a bit of a negative story, but Japanese animation has very limited production budget and time. Within this very limited time, we tried our best to create high quality animation. As a result, routine work for animation production in Japan were divided into smaller pieces to enable each section to work concurrently. And it is quite often that the productions of Japanese animation depend on the professional experience of each staff.

Because production time is very limited, there is no way to have additional takes, and discussions among creators have to be the shortest time possible. In the case of producing animation weekly, most of the time, you really have to get only one final take at the next step after just one meeting. To be able to make a decent visual expression that is needed for it to be a product, it is often worked out like “It would be fine like this”, based on the experience of each staff had on a tacit understanding.

I think that our experiences in responding to this limitation in budget and time leads to the Japanese’s own expression in animation and all the creators share its unspoken rules. This would have led to the Japanese animation’s own stylistic beauty.

In which stage of the project does Bamboo Inc. start taking part, as an example?

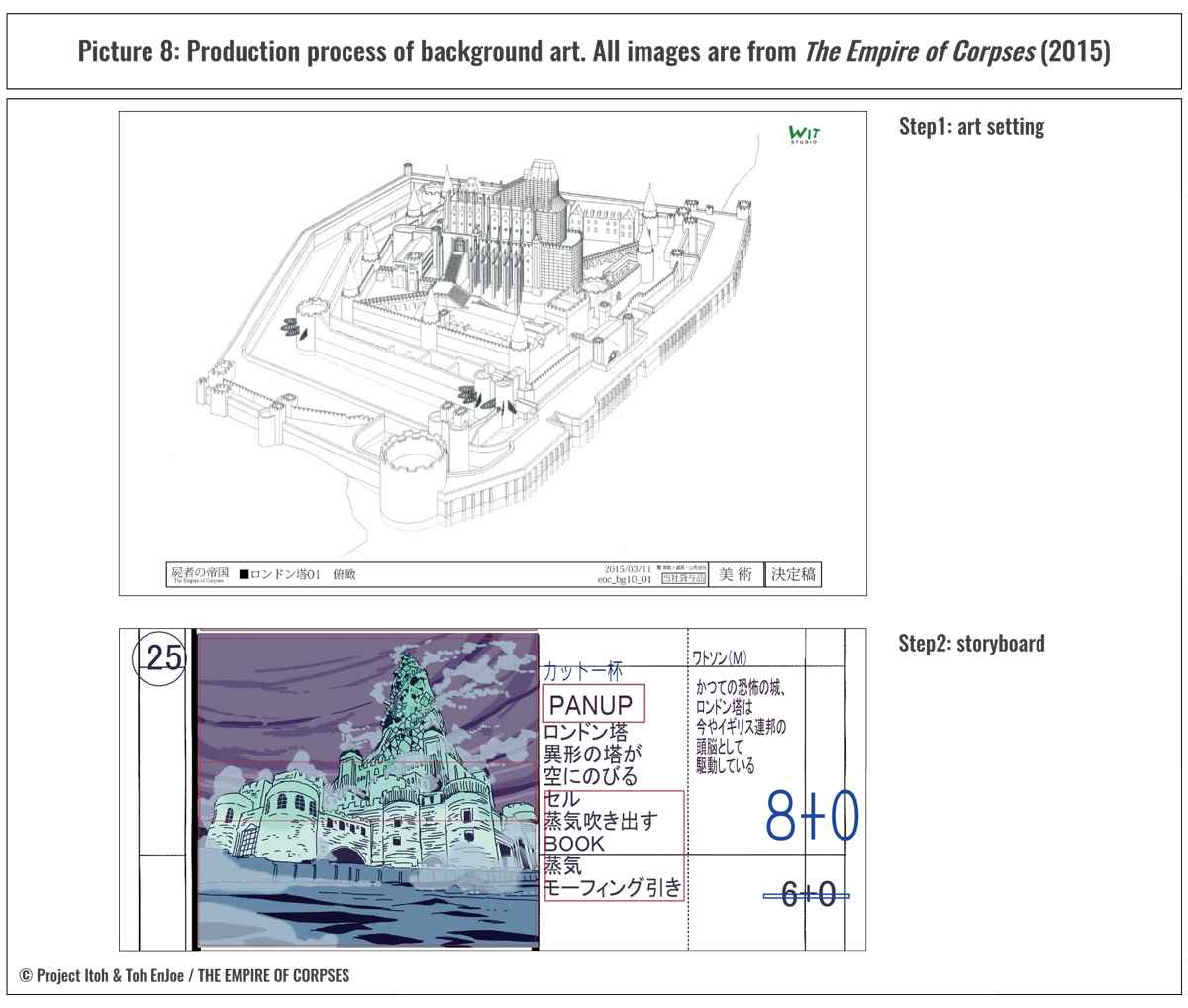

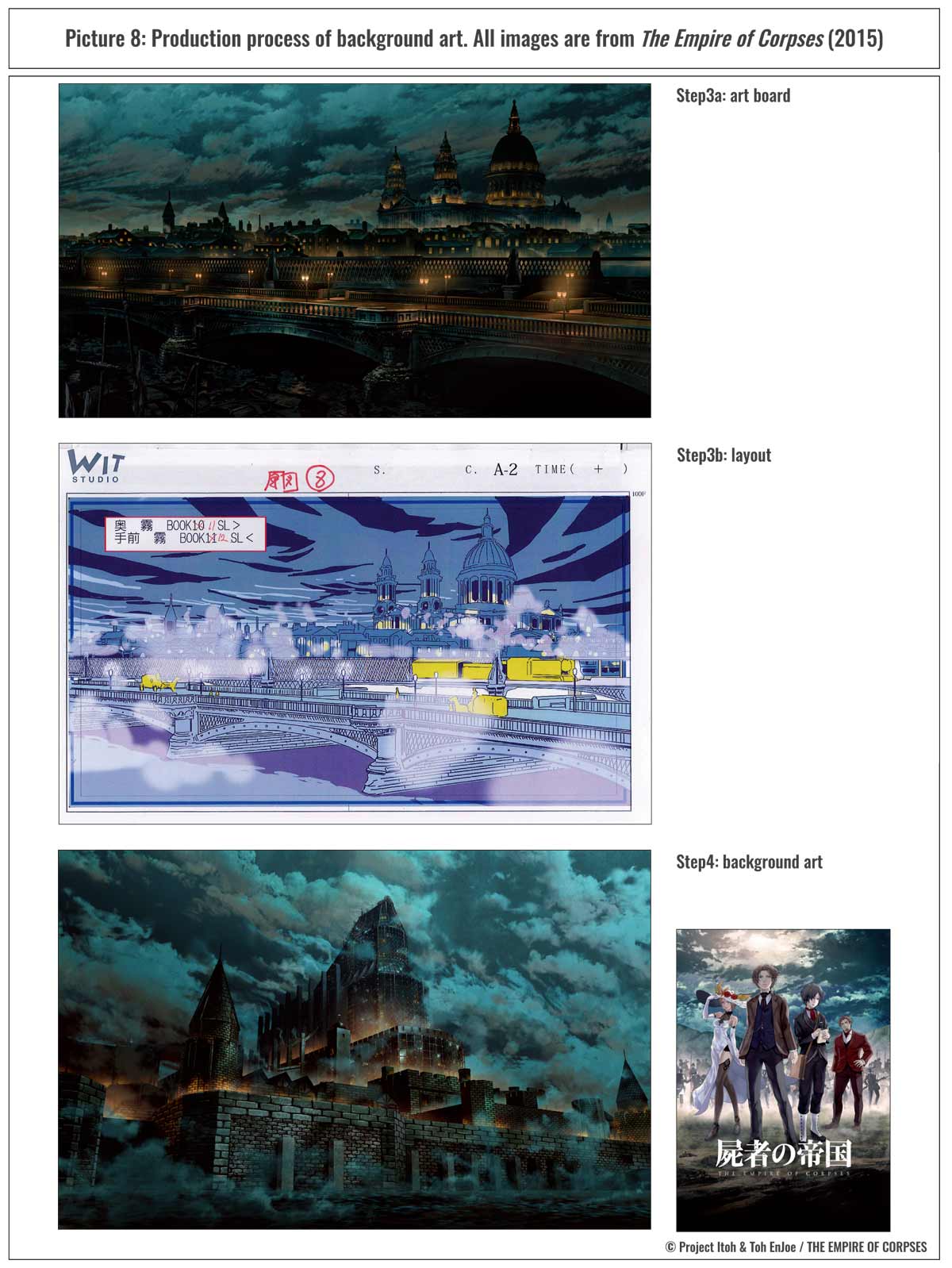

In a step before us, there is a section called “art setting”, where designs are completed with line drawings. They often take part in the project from the scenario writing phase.

Next, when the art setting and scenario become mostly ready, a director starts working on the storyboard. This is when we start participating with our work on an “art board”, such as deciding the color for each scene or drawing an atmosphere not depicted in line drawings.

In parallel with the process of art board, animators start to draw layouts based on the storyboards. To be precise, the process of layout starts a little bit before the process of art boards.

When both layouts and art boards are ready, we begin to draw background art for each cut. At the same time as we are drawing background art, keyframes and in-betweens are drawn based on layouts and then colors are painted onto them. When everything gets together, the next step is compositing, as in compositing cels and background arts (Picture 8).

The Creation of a Fantasy Universe

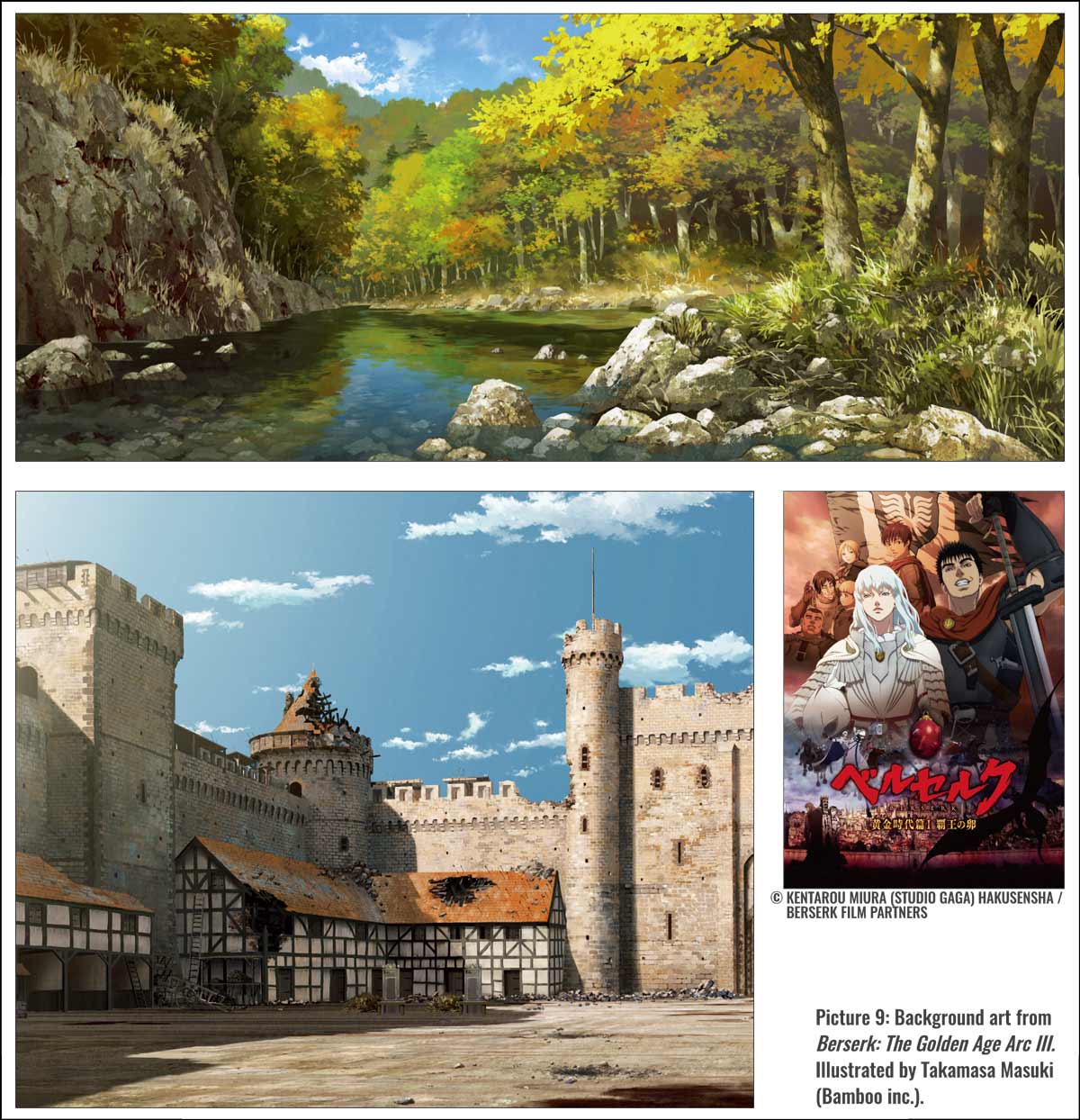

You depicted the fantasy world in the feature film Berserk: The Golden Age Arc III and the TV animation series Sword Art Online, which has many fans in the USA and Europe. How did you create them?

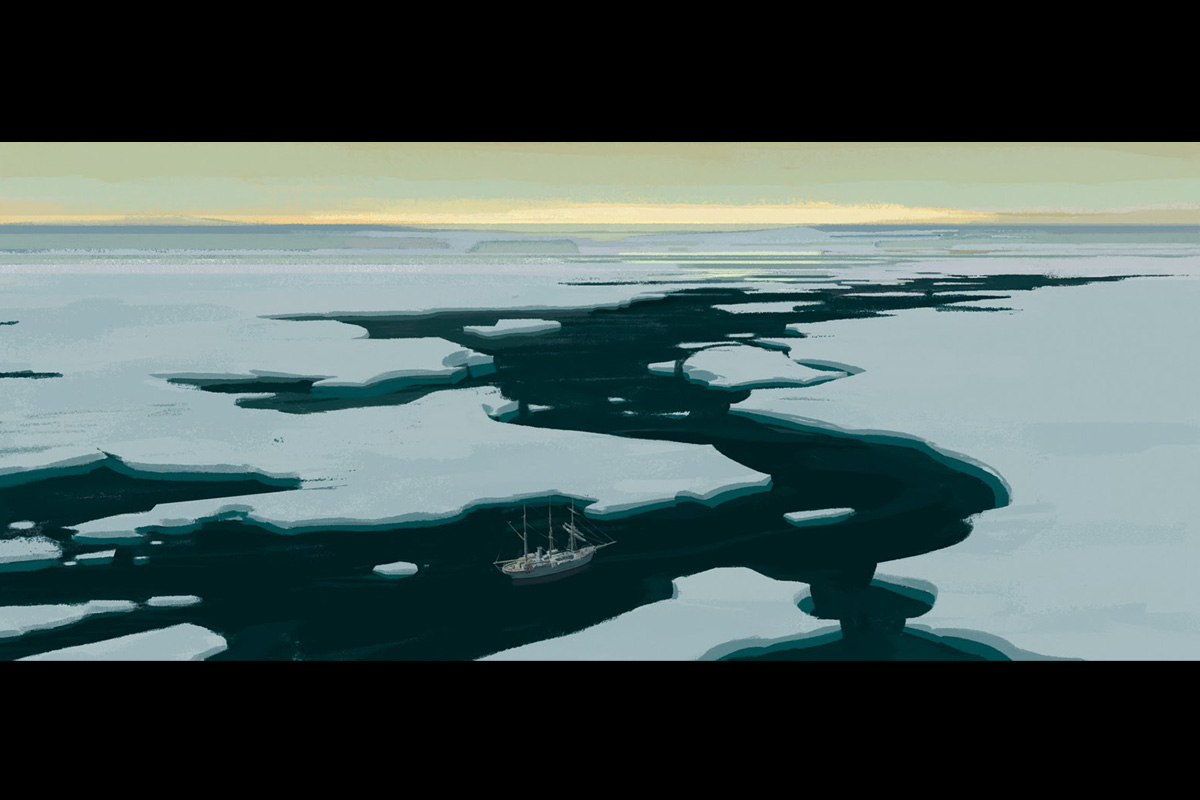

As Berserk sets in a fictional Anglo-French war between 13th and 15th Centuries, we organized a trip for a viewing location to research topics such as how siege warfare of a castle was waged and structures of a castle for the protection in that time. Then we drew background art that would reflect them as much as possible. In that sense, a trip for a viewing location is a prerequisite for this work.

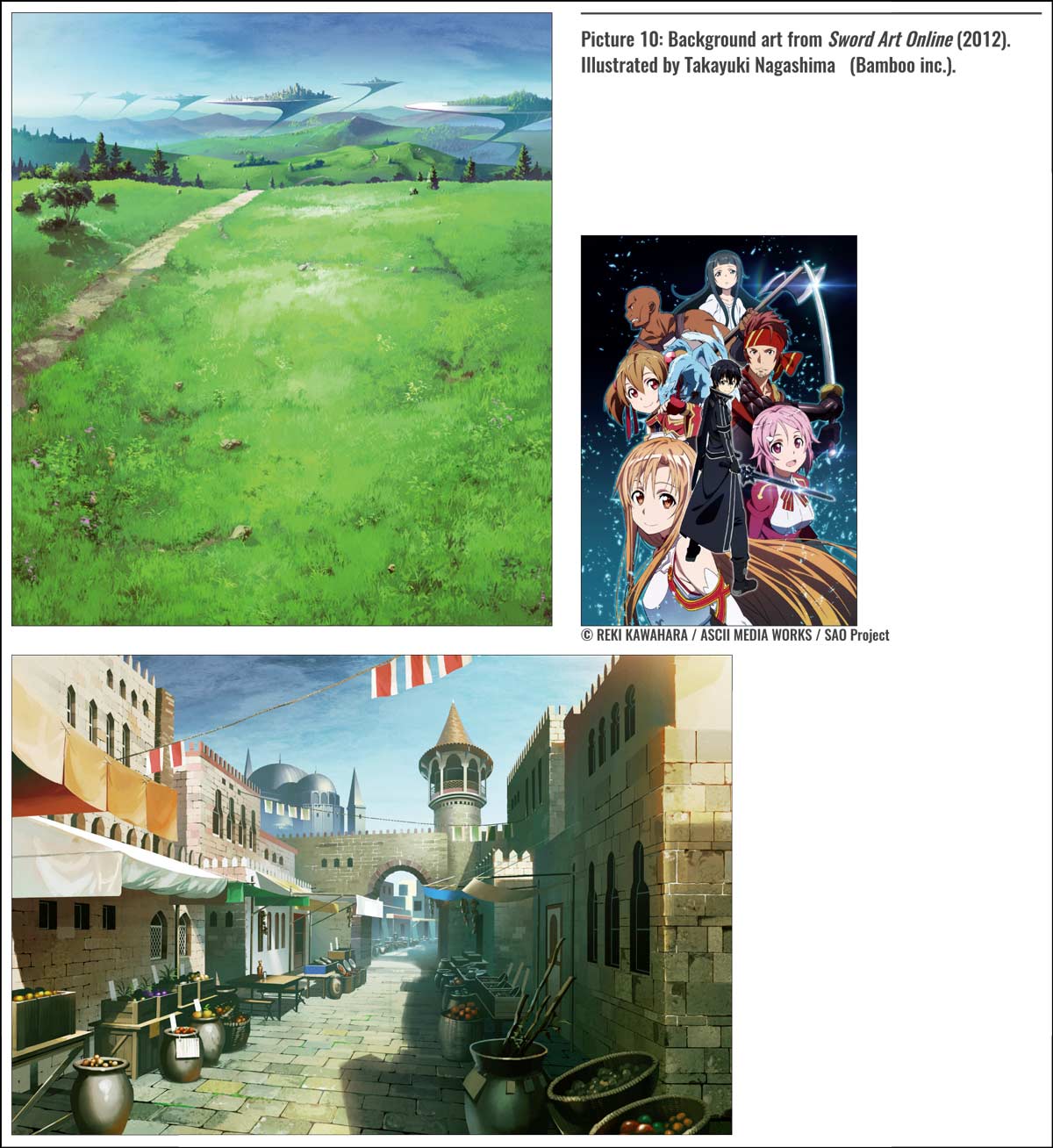

On the other hand, Sword Art Online sets in a stage inside of a fantasy video game. I think that every motif for this world can be found in the universe of European fantasy works, which we used to read when we were small, like classics The Never Ending Story and The Lord of the Rings.

So it is impossible to organize a trip to view locations for Sword Art Online. Yet, we would like to have reality in the world of fantasy, which does not exist for real. To do that, we drew by reflecting our knowledge and information from our daily lives. We also tried to draw items designed, which do not exist in the real world, to reflect changes in light and color naturally. Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit is also a story in a fantasy world, but the scenery and atmosphere of the universe is totally different, because we tried to draw an Asian fantasy world.

Were the visuals for the universe of Sword Art Online decided during the layout stage? Or was it created at the stage when Bamboo Studio draws background art?

In a case of the project for Sword Art Online, first of all, concept art were drawn by Sotaro Hori, who usually works on video game projects. Besides that, Yorinori Shiozawa, a freelance art designer, designs the universe and then most of the designs are decided. Then, at the step where we drew an art board, Takayuki Nagashima from our studio takes part in the project and the drawings start taking shape.

Regarding layouts, it is almost impossible to manage all scenes to follow the same designs of the universe, because so many animators get involved in the TV series and the production schedule is very tight, as I previously mentioned.

For one TV animation series, 20-30 animators got involved, so 20-30 different kinds and styles of layouts were produced. Among various layouts, there are layouts boards that make us want to follow it, although it is different from the baseline designs of the universe or storyboards, and layouts that we need to correct. We, art directors, control the design of all these different layouts as a whole.

Sometimes, I adapt our drawings closer to a unique layout design, re-draw it, or tell those visuals to background art staff to share the new designs. We complete our drawings by doing those kinds of arrangements flexibly in real time on-site. There is a position called animation director who controls the design and quality of layouts at a certain level, but at the end, the art director ensures consistency of visuals one last time.

Challenges with 3D Stereoscopic Vision

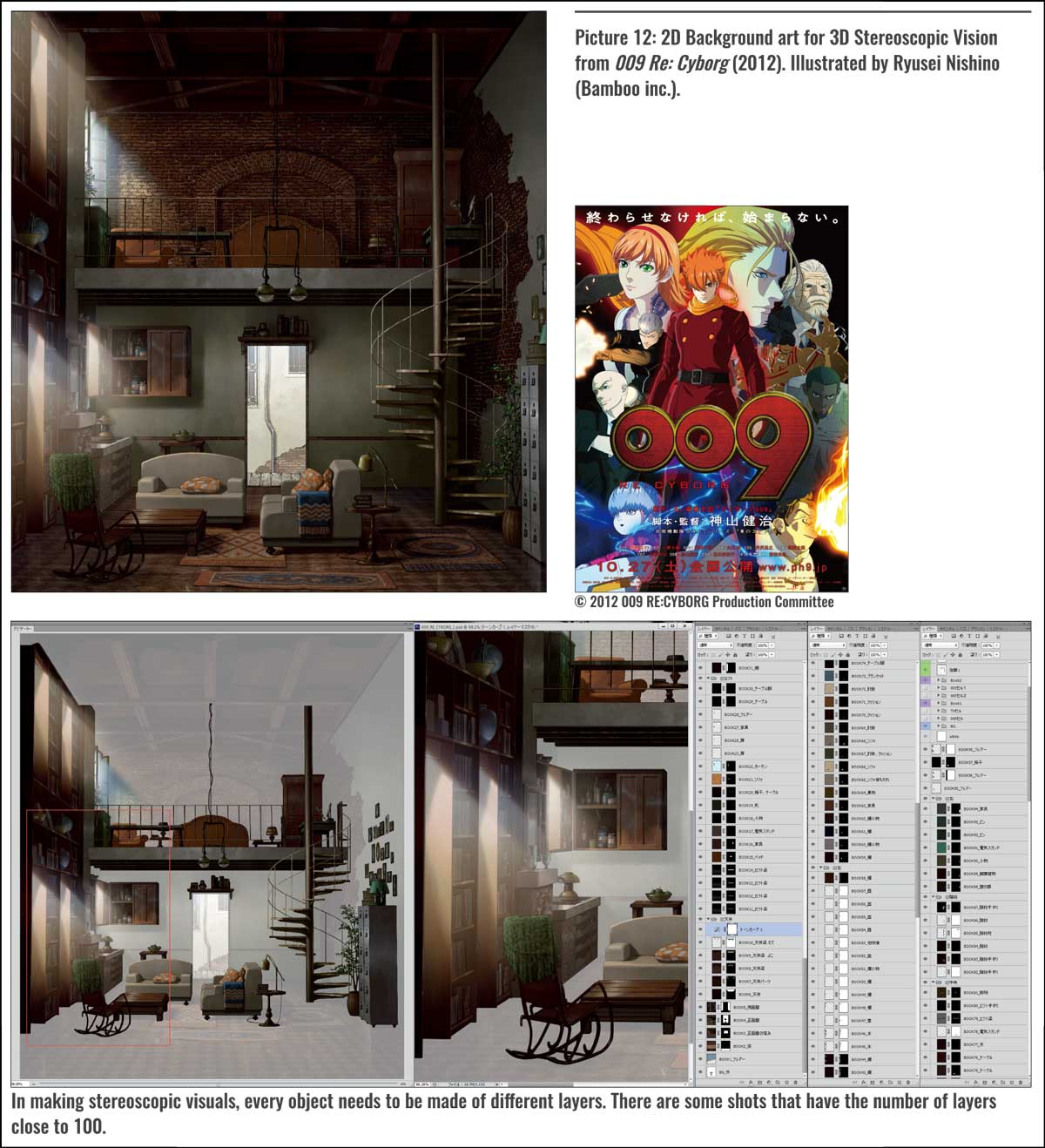

Bamboo studio basically draws 2D background art, however, 009 Re: Cyborg (2012) is a stereoscopic animation. How did you produce the background art with 2D drawings?

As you say, we draw background art in 2D, but we made it to visuals that can be stereoscopic at the compositing stage. In other words, we made the visuals with the perception of depth that can be recognized when you watch them with 3D glasses.

To be used in stereoscopic visuals, we draw objects in more separate parts on different layers, based on the perspective and distance from the audience’s eye, when we draw 2D background art.

To make stereoscopic visuals, it is filmed with two cameras placed in both left and right, for the left and right eye respectively. Then, due to the slightly different angles of the left and right cameras, viewers feel that the visuals pop out or the elements of the visuals have different depths.

We used to call visuals that were filmed by two cameras, “L channel” and “R channel”. Because of disparity, for example, it could be that one object cannot be seen in L channel because it is hidden by another object in the view of L channel, but it can be seen in R channel in the same scene.

In other words, we need to draw objects that would normally be hidden by another object in a conventional 2D animation filmed by one camera. So, we drew many more objects than usual for each scene. As I don’t know the technical details of filming and composition, this is only in theory.

So, you drew objects in each scene, which were hidden by some objects from a certain view, on each different layer by separating the structure of one background art into a number of parts.

Yes. That’s why the number of layers for each background art data increased significantly. Even though the number of layers for background art of regular animation is about from 2 to 4, some of the scenes for 009 Re: Cyborg had the number of layers close to 100.

We drew in 2D as its appearance; we did not use any new techniques. SANZIGEN Inc., who has the production technique and know-how for stereoscopic view, participated in this project. So the 2D becomes a stereoscopic view from the production step where SANZIGEN studio works on.

The Projects to Take Part In

You have participated in various projects, which were highly regarded domestically and internationally. How did you decide which projects to take part in?

We don’t select projects which we take part in from us. Basically, we take part in the projects if the schedule allows when we receive some offers. Even when our schedule is full, we would say “we cannot take any projects during this time, but this time would be fine” and then the schedule could be adjusted and we can participate. If the scheduling does not go well, sometimes we have times when we don’t have any works.

How do new projects start and receive offers in the Japanese animation industry?

Some people may think that creators or studios would raise hands to projects that they would like to take part in at the stage of ideation. But that kind of case is very rare.

Because, by the time the general public know about a project, the project team is already formed. In most cases, at the stage where the project team starts contacting a background art studio that they wish to work with, we, Bamboo studio, learn about the project and accommodate ourselves whether we can accept that project or not.

How does a project team get in touch with you? For example, would it happen in casual talk such as when you have small talk with a director at a pub, and casually brings up: “actually we have this kind of project”? Or, does the project team contact your studio by an official business email?

We have both cases. It’s case by case. In case of when a director or producer appoints us directly, as you have just said, while drinking together at a pub, we have a conversation like, “We are going to have this kind of project next year. What do you think?” and we answer, “It sounds fun!”, then our participation could be decided.

It has been long since our studio started working with Director Kamiyama, who directed 009 Re: Cyborg. I still remember well how we started our first work with Director Kamiyama on the TV series Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex (SAC) (2002).

One day, while I was reading some magazine at a convenient store nearby my home, Director Kamiyama came in and asked me “Are you available, after the title you are currently working on, Mr. Takeda?”, then I answered, “Nothing is scheduled after that at the moment” and he continued, “We have this kind of project”. So I said, “Please let me know the details!” Next week, I received a call from a producer and we could take part in the project.

I assumed that there were several candidates of background art studios, surely, but having a talk with the director at the convenient store by the pond in Shakujii park at midnight coincidentally led us to our participation in SAC.

Various opportunities lead to works.

Yes. It is not that every project is decided at the official places. There are cases that our participations in the projects are decided like while we are having some food with someone who are introduced by another person, then we talk like, “Well then, let’s do something together next year”.

Participation in Overseas Projects

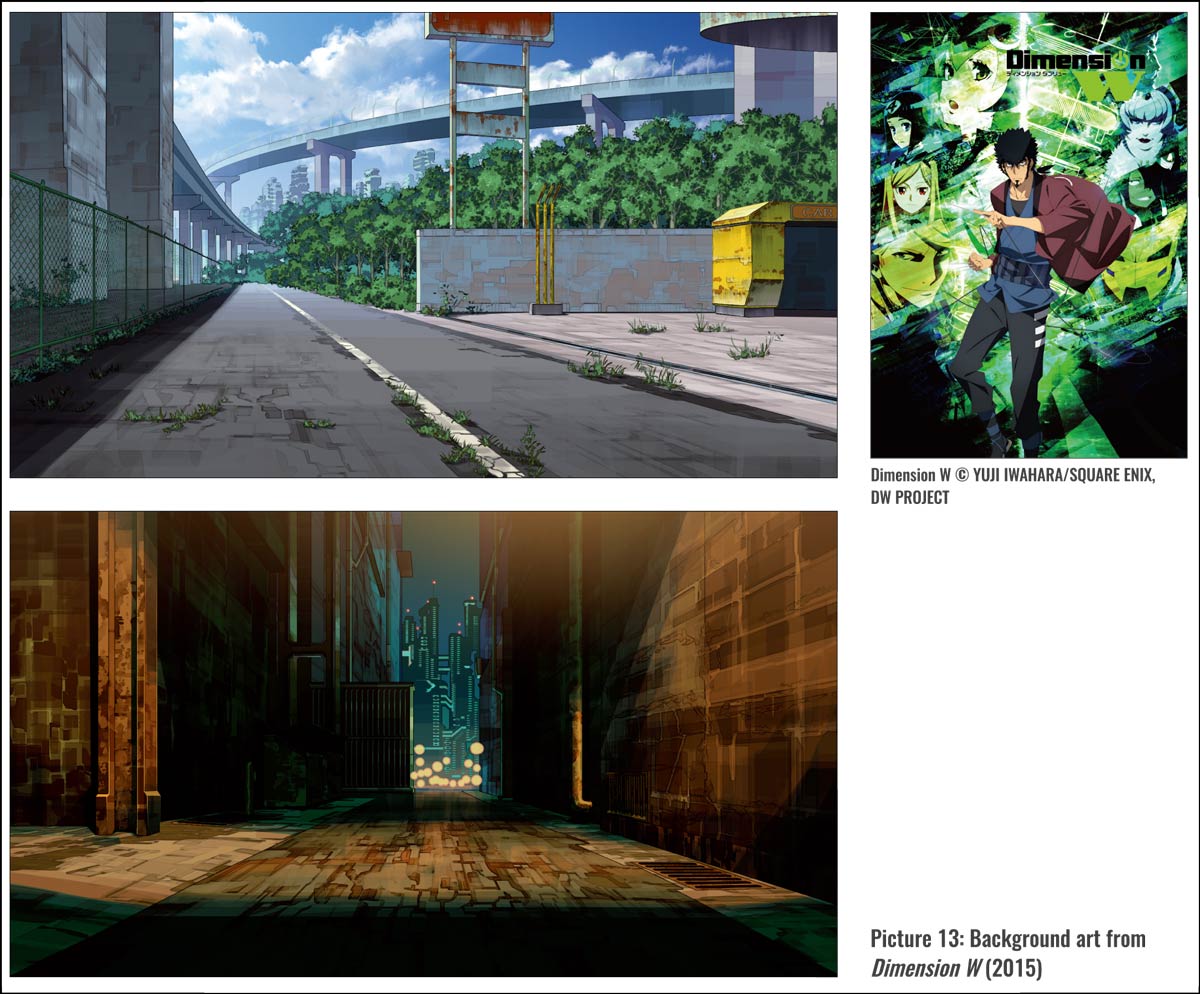

Lately, some of the works that Bamboo studio participated in were international projects such as the TV series Dimension W (2015), which Funimation, based in North America, took part in and created the promotional video for Genreidowa from China. How did you become involved in those kinds of international projects?

Neither of them I approached proactively. It happened to be that oversea companies participated. Production of Dimension W is all done in Japan and I learned that Funimation would stream it in North America later on. In terms of Genreidowa, the funder and a person who is like a general director are in China, but the animation is produced mostly by Japanese staff. Its production process was like, a Chinese person who has been working in Japan for a long time played a role of a production producer and a contact point to gather resources in Japan. And completed all the visuals were brought back to China from Japan for the client’s check.

Do you think that the number of international project is increasing?

I think it is increasing. We produced PV for another client, which was produced by a Japanese production company, but has an overseas company as one the project members in the same way.

Future Vision of the Studio

I would like to ask you about the future of your studio. What kind of animation projects would you like to get involved in and how would you like to manage the studio?

Regarding the future vision of the studio, my answer is rather vague but it is important for us to show what kind of drawings we can draw to respond to what producers and directors of the day want to create. So, I would like to keep focusing on that.

Working in Background Art

Would you have any advice to who would like to work for the animation industry in the future?

I think that the most common reason why people, who work in the animation industry, want to work for animation is that they like watching animation, presumably.

However, the work of animation background art is not necessarily a job for those who like animation.

For example, it is not rare that a student who learns drawing at an art university may find that there is a job for animation background art for the first time when they search for a job in drawing, although they may not like animation much.

As you know, there are not so many career choices that your acquired skill at art university can be used in, actually.

For instance, if you could get a position as a designer at a game company, it is attractive financially, but the opportunity is limited. Opportunities to get positions such as in advertising and interior design are not so many, either. So there are not much jobs that you can use your skill of drawing, which would lead to income. In a sense that drawing can be your work, quite a number of graduates of art universities select animation background art as work.

As you have been working for animation background art for a long time, where do you feel satisfaction, achievement and enjoyment in your job?

To be honest with you, during the time, when we are drawing background art, is just laboring for us. We draw as a job and have to complete drawings by the deadlines so that it is a dilemma to our own desire to draw one piece as much as we want. Having said that, I can say I am happy at the moment when I finished drawing.

When I feel achievement most is a time when my finished background art is completed as a scene of animation and I can feel that my aimed psychological description is expressed well.

As we drew paintings with an aim to complete the final visuals of animation as background art, not completing drawings as a hobby, I get goosebumps if, in one scene, when the sound of footsteps that a protagonist walk on the cold alley matches to the sound that I imagine from my drawn stone pavement. I am pleased if a sound, darkness of alley, humidity and so on that I imagined during drawing match the lighting, color of characters, effect sound and direction etc. of the final visuals perfectly.

For example, there is a scene that a sound of footsteps changes from walking on a road where snow is cleared to stepping into fresh new snow. That is how a sound director differentiates sounds by looking at finished visuals. For me, the process where many different people complement different parts one after another to complete visuals of animation after our drawings of background art is fun.

I forgot to mention a very important thing. I think it can be said that background art is the section of animation production in which your drawings most directly contributes to the film. The impressive feeling, which you have when your drawings appear on screen, stays the same.

Also, responses from viewers motivate us more than ever thanks to internet streaming services and social media. We never imagined the time when we can see the reaction of viewers saying like “That background art is good” on the night when that episode broadcasted would come.

Do many people in the animation industry check comments written by viewers on Social Media such as Twitter?

Yes, there are quite number of people who check that. There is a person who really worry about it and another director does not want to see any of them at all by saying things like “I want to go to the world where no internet exists after releasing a film” (laughs). It can’t be helped to look at reputations by viewers in this internet age.

(Originally interviewed in Japanese)