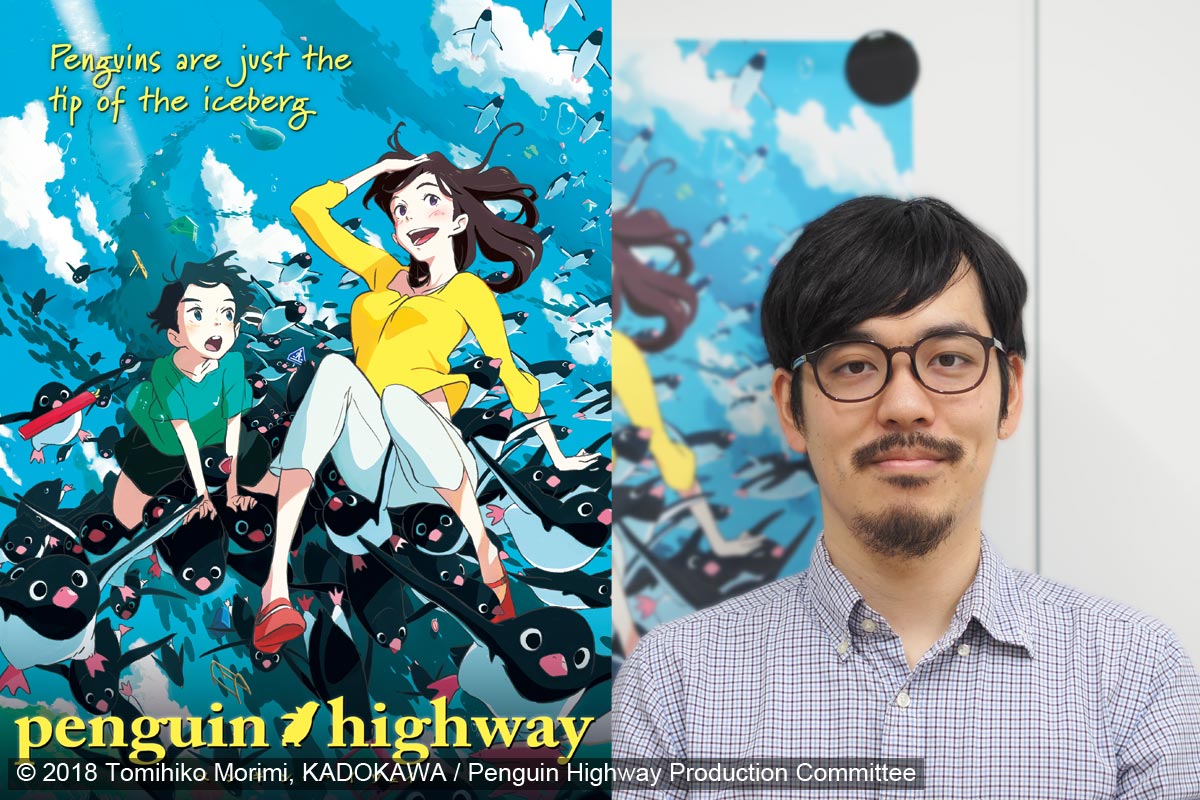

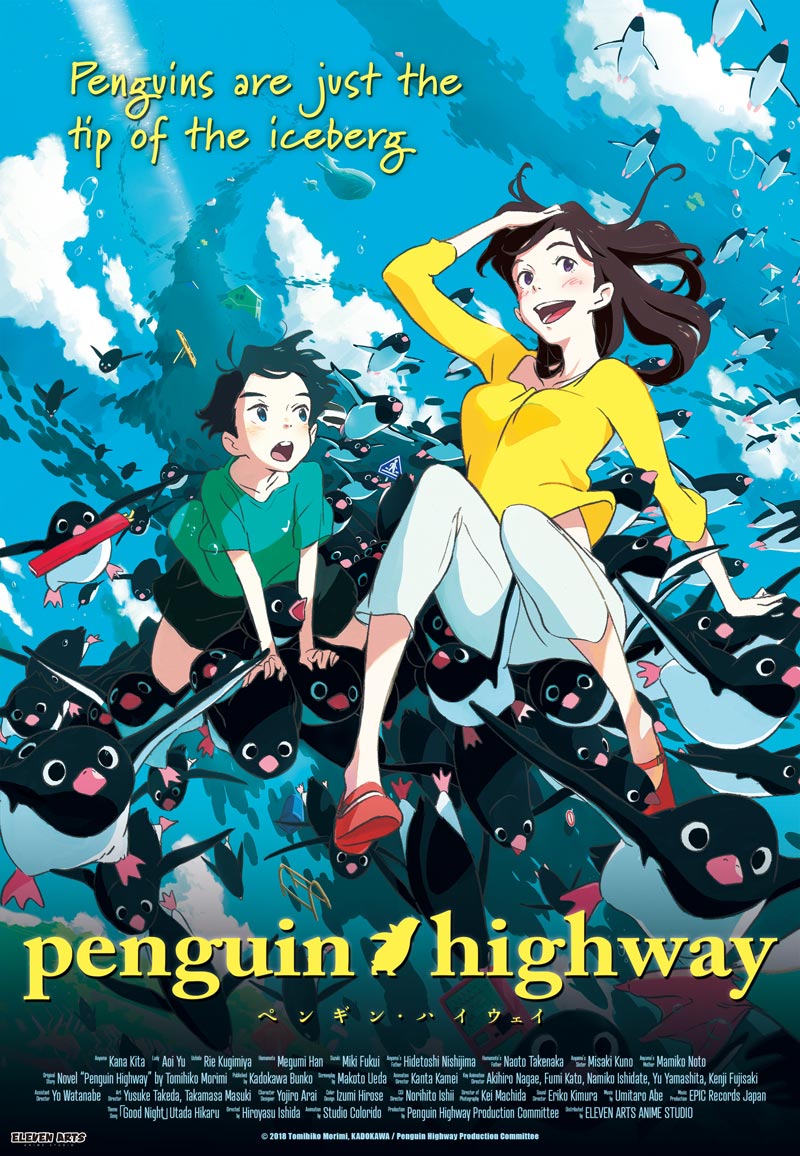

Penguin Highway

Penguin Highway

Director: Hiroyasu Ishida

Scriptwriters: Makoto Ueda; Adapted from Penguin Highway by Tomihiko Morimi

Character Designer: Yojiro Arai

Artistic Director: Yusuke Takeda (Bamboo) and Takamasa Masuki (Bamboo)

Music Composer: Umitaro Abe

Animation Production: Studio Colorido

Format: 118 minutes

Technique: 2D digital

Synopsis

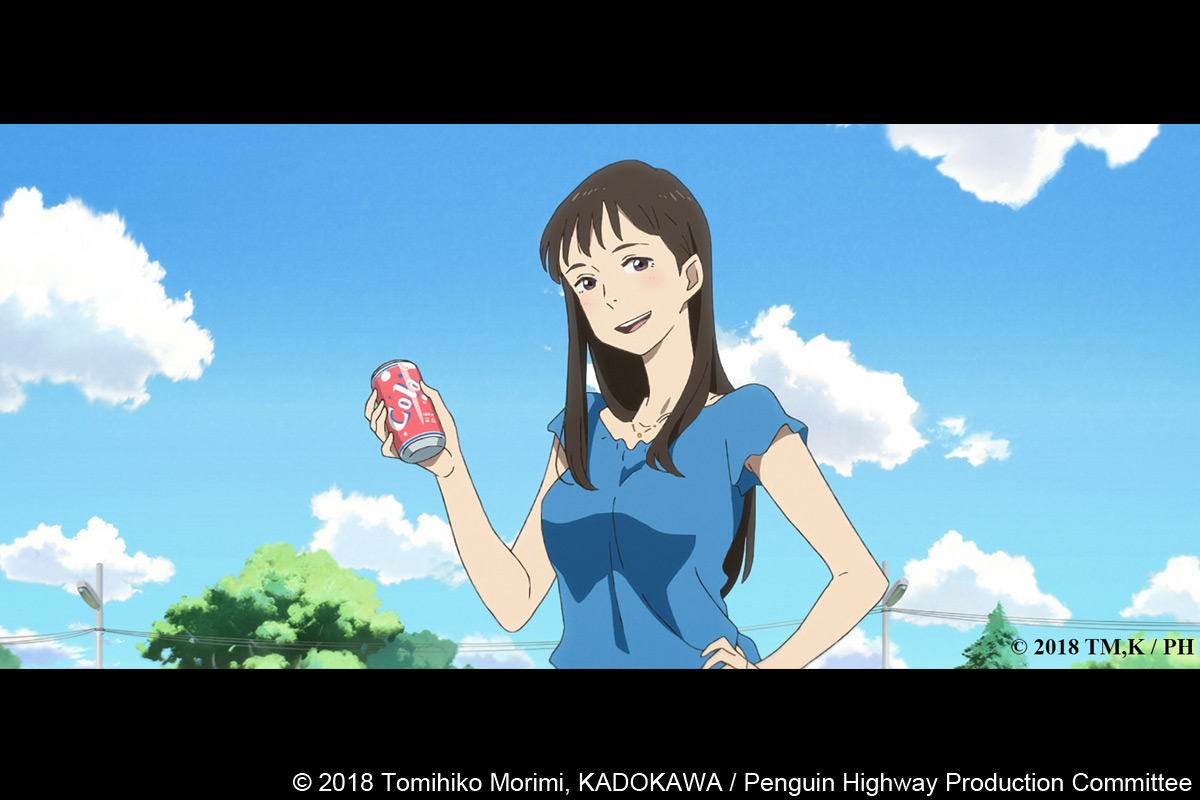

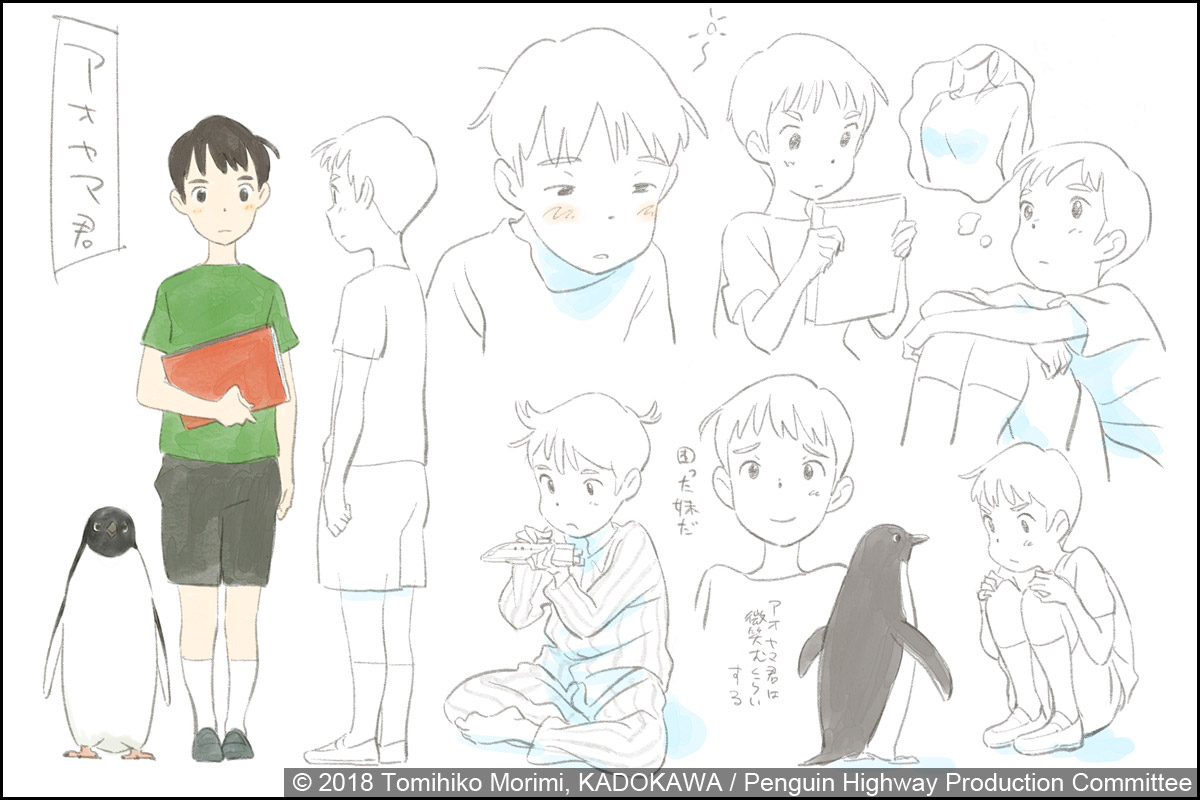

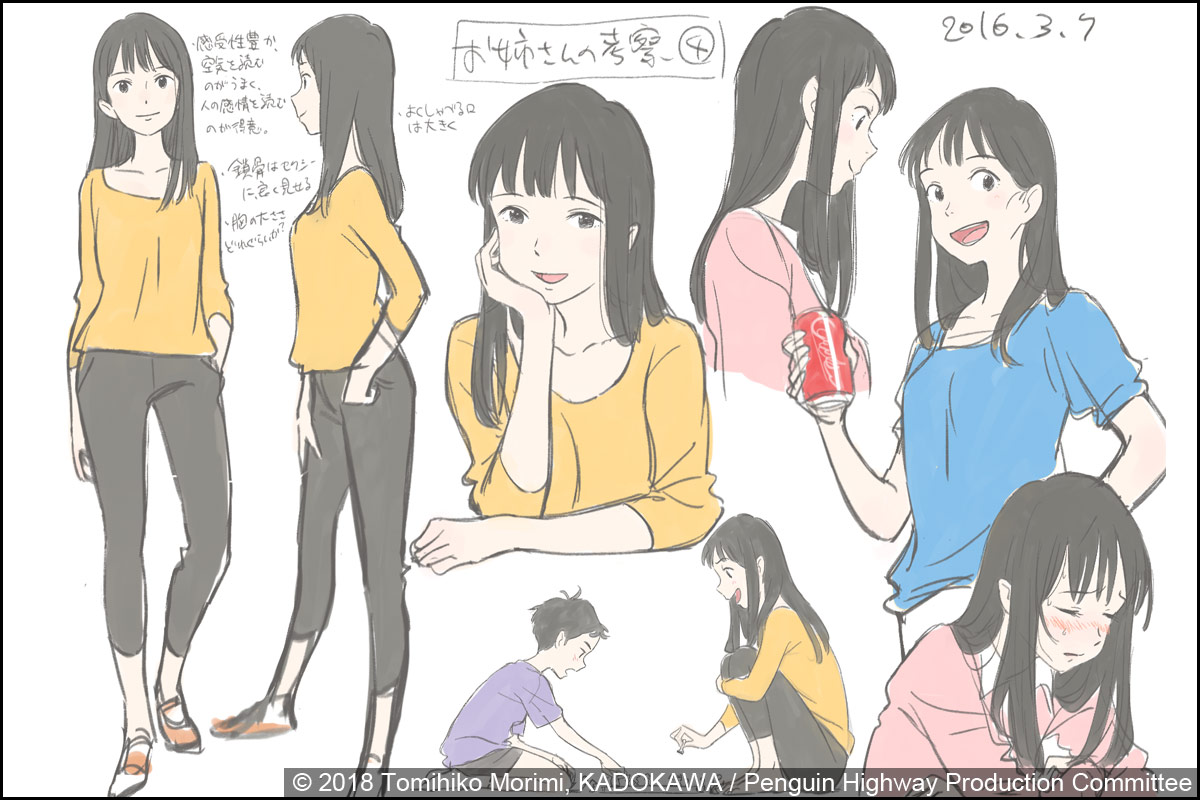

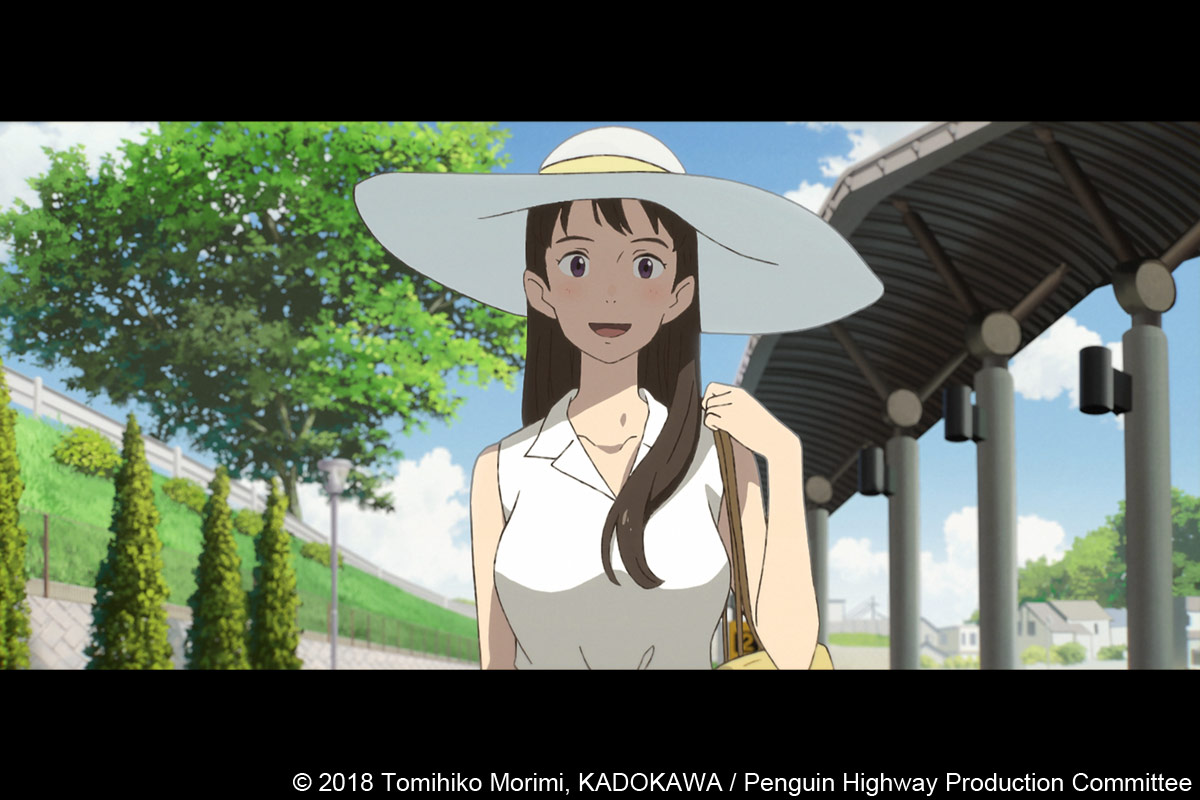

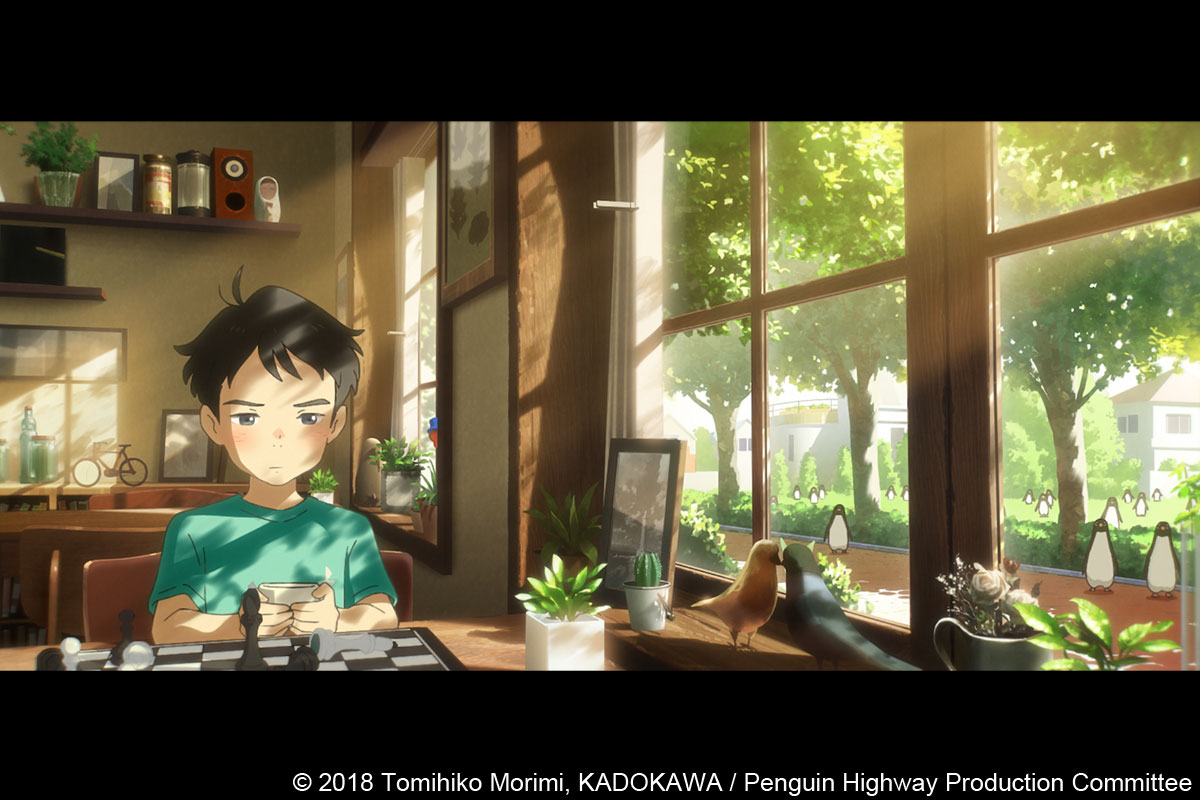

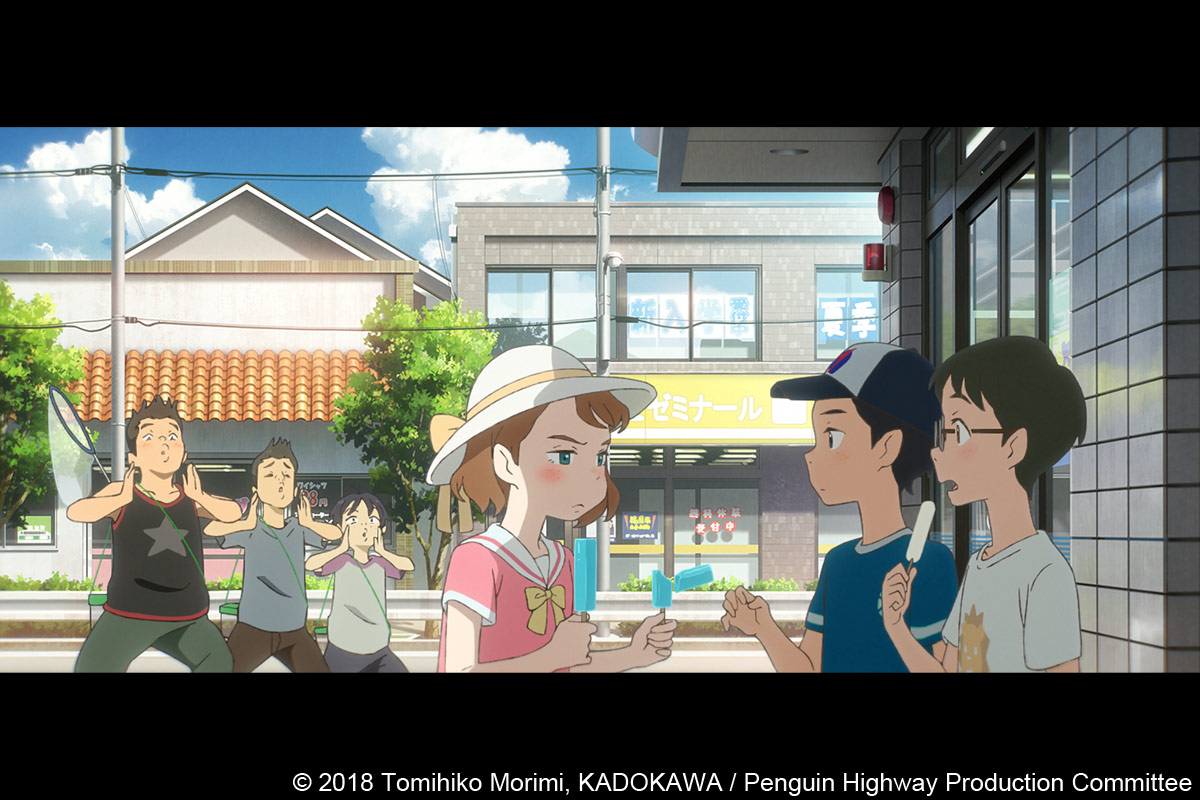

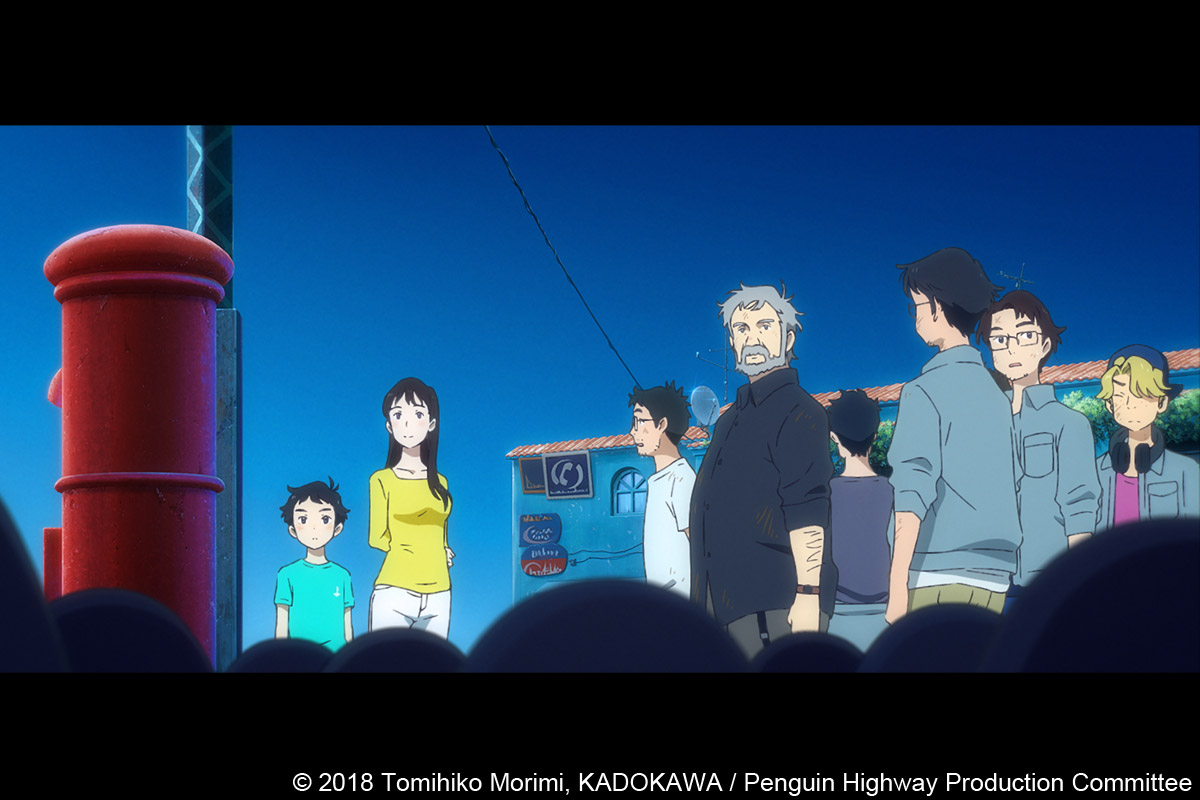

A boy in his fourth year of elementary school, named Aoyama, is learning more and more each day about the world around him, and taking notes of them. He is smart and studies every day, putting his effort, so that he thinks he will be a great man in the future. The most interesting thing for Aoyama at the moment is a young woman that he calls “Onee-san”*1, who works for a dental clinic that he goes to regularly. For him, she is a freewheeling adult who is very friendly, but mysterious in some ways. So, he is researching seriously about her as well.

One day, about a month before the summer holidays, suddenly many penguins appeared in a suburb he lives, which is a residential area far from the sea. While the people in town had been in panic, the penguins disappeared. Where on Earth did they come from, and where could they have gone? The boy, Aoyama, started to research about the “Penguin Highway” to solve the mystery, and then he saw that the can of cola “Onee-san” threw abruptly was transformed into a penguin. She declared with a smile to Aoyama, who was staring at her blankly, “Why don’t you solve this mystery? Can you do that?”

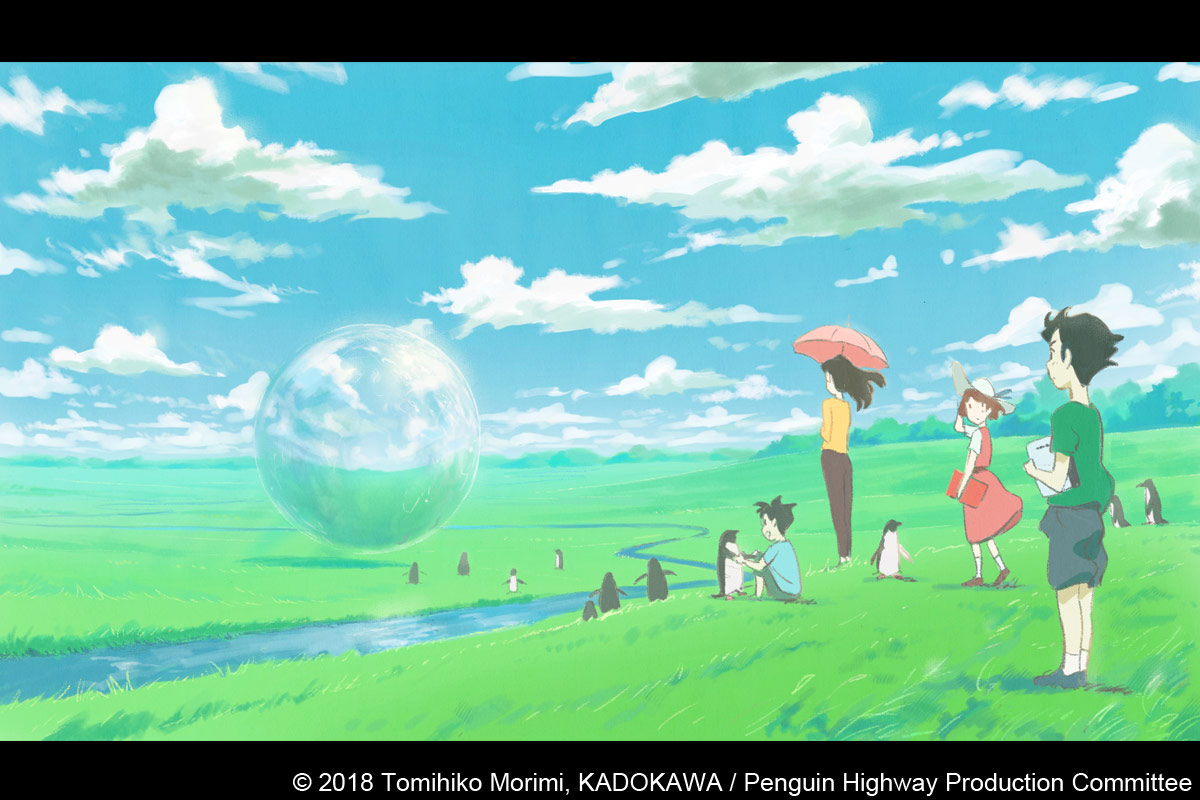

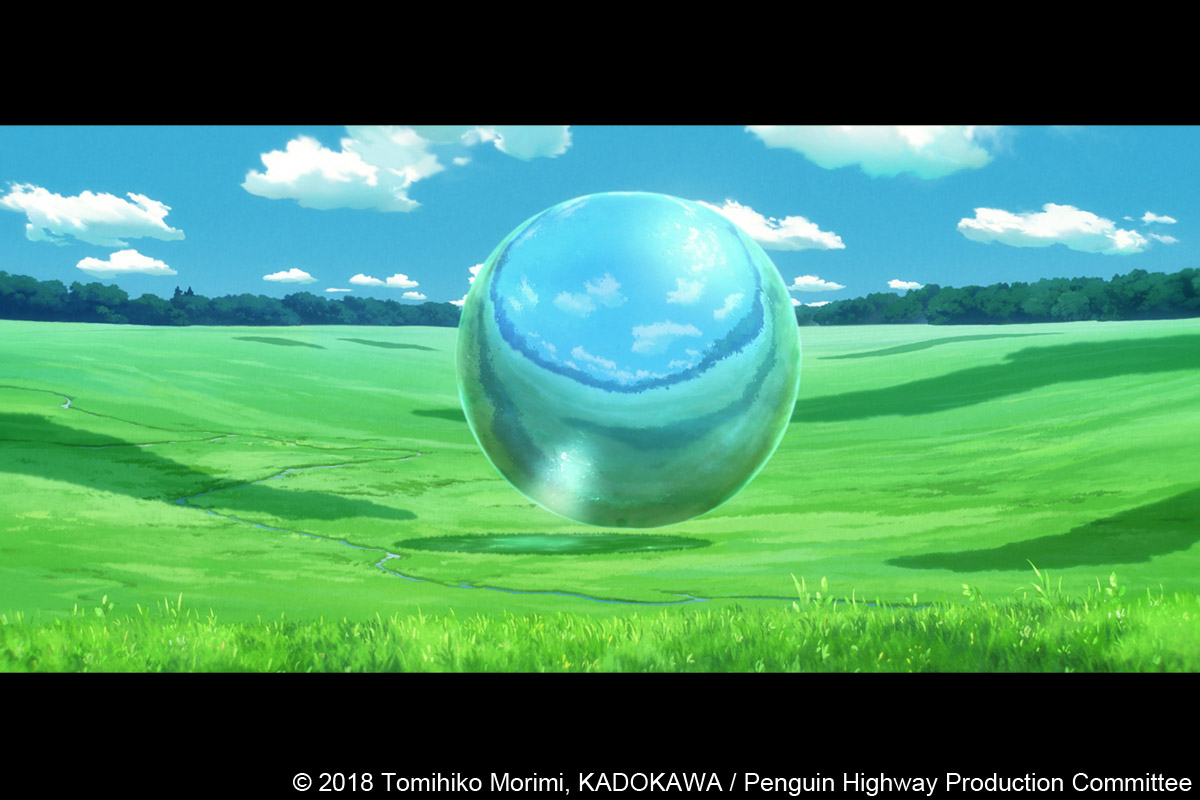

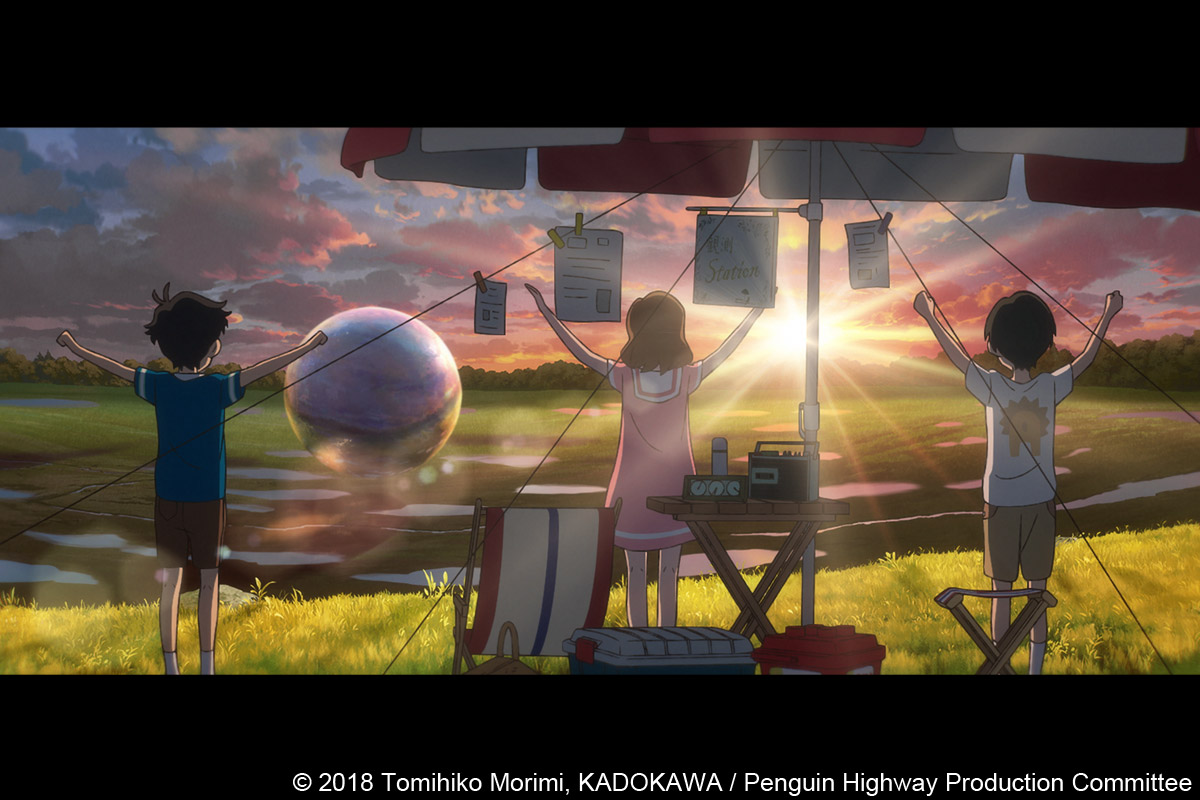

On the other hand, Aoyama and Uchida (a boy who is doing some research in the town with Aoyama as part of their extracurricular activities) are told from their classmate Hamamoto that there is a big, floating, transparent sphere in a grass field deep in a forest. Aoyama, Uchida and Hamamoto proceed with their research about the floating sphere, which they call “The Sea”, as well as their research on the mystery of the penguins, despite having their research disturbed by Suzuki, the boss of the kids of their class, and his followers. Then, before long, Aoyama starts to think that there might be some connection among “The Sea”, the penguins, and “Onee-san”.

Will he be able to solve the mysteries of “Onee-san”, the penguins, and “The Sea”?

*1: Japanese children frequently refer to a woman who is older than them as “Onee-san”, instead of calling her by her name. In the film, the name of the woman who works for the dental clinic is not uncovered and Aoyama calls her “Onee-san” throughout the film.

Penguin Highway is a Japanese animated feature film targeting an age range from children to adults, and is based on a novel of the same name written by Tomihiko Morimi, a popular novelist in Japan. The film was theatrically released in Japan on 17th August 2018. The film is planned for its North American theatrical release on 12th April 2019. Preparations for bringing the film to European cinemas are underway.

Some of Mr. Morimi’s novels have been adapted into animation*2, and among them Penguin Highway became the third title of his to receive an adaptation. The director of the film is Hiroyasu Ishida, an up-and-coming young director from Studio Colorido who was spotlighted in Japan for the first time when he made Fumiko’s Confession (2009) as his graduation work. Since then, he has been making animated shorts such as Sonny Boy & Dewdrop Girl (2013).

Studio Colorido, who developed the animation, is a rising young Japanese animation studio that is quickly gaining momentum.

This film project was presented at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival 2018 as one of the animation projects for the “Work in progress” sessions by Mr. Ishida, the director, and Yojiro Arai, the character designer and animation director. Ishida told us that he read more than 10 novels that interested him when he decided to make an animated feature based on an original story, and he selected Penguin Highway among them because he was attracted to the fact that it is a good sci-fi/fantasy story, and yet the story carefully describes the daily experiences and troubles in the ordinary daily life of the protagonist, a boy in his fourth year of elementary school. The author, Mr. Morimi, won the 31st Japan SF Grand Prize with the novel, Penguin Highway.

We could have a precious opportunity to hear from the director Hiroyasu Ishida about a variety of things on the film, in detail. We are happy to deliver his words to you.

*2: The other animated adaptations of Mr. Morimi’s works are The Tatami Galaxy, an animated TV series, and Night Is Short, Walk On Girl, which became an animated feature, and both animated titles were directed by Masaaki Yuasa. Night Is Short, Walk On Girl won the Best Animated Feature at the 41st Ottawa International Animation Festival.

Interview with Hiroyasu Ishida

Start of the Project

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Could you please let us know how you took part in the film project?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Mr. Koji Yamamoto*3, the chief producer of an animation programming block titled “Noitamina” at Fuji Television Network, Inc. (Fuji TV), gave Studio Colorido an opportunity to make a short animation titled Paulette’s Chair for a broadcast slot in 2014 on kind-of a trial basis, and I directed the short film.

Then, we were able to produce our mid-length film Taifu no Noruda through Mr. Yamamoto as well in 2015. Yojiro Arai directed the film and I did the character design and animation direction for the film. Mr. Arai also works for Studio Colorido and he was responsible for the character design and animation direction of Penguin Highway.

After we completed the film Taifu no Noruda, Fuji TV gave me a broad suggestion: “Let’s do something together. If possible, could you please plan a full-length feature film?” That was the beginning of the Penguin Highway project.

I was very happy and honored when they kindly suggested a project plan for making an animated feature with me. On the other hand, I wondered if I could really manage directing a full-length feature film. Actually, I had thought about an alternative plan for a mid-length animation project, but when I encountered Penguin Highway, the original novel, I thought that it was a very good, attractive story, so I could prepare myself in assuming the role of director for a feature film, if I could make a film based on that story.

*3: Mr. Yamamoto established TWIN ENGINE Inc., an animation production company, in 2014 after leaving Fuji Television Network, Inc. Studio Colorido is one of the subsidiaries of TWIN ENGINE and he serves as chief executive of Studio Colorido as well.

HN: What kind of process was there, from just after you decided in your mind to make a featured film based on Penguin Highway, to the film project getting off the ground?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Actually, it took quite a long time to get the permission from the author, Mr. Morimi, to make a film of the original novel.

At first, I was in deep thought with the original story and considered whether I would honestly be able to bring this original story properly into an animated feature film format.

After that, I prepared a proposal. I drew the visuals of the characters and the universe of the story, and storyboards which followed the story structure of the original novel. Then I showed the proposal to Mr. Morimi, but I couldn’t get the permission from him at that time.

Mr. Morimi was apprehensive about my design of Aoyama, the main character, in my proposal. I think Mr. Morimi probably couldn’t see how the dark or mysterious parts of the story would be depicted from this proposal, because many of my past works were positive and cheerful animations, and Penguin Highway is a story of both light and shadow. He was also worried about my age because I was quite young as a director for a feature film in the Japanese animation industry.

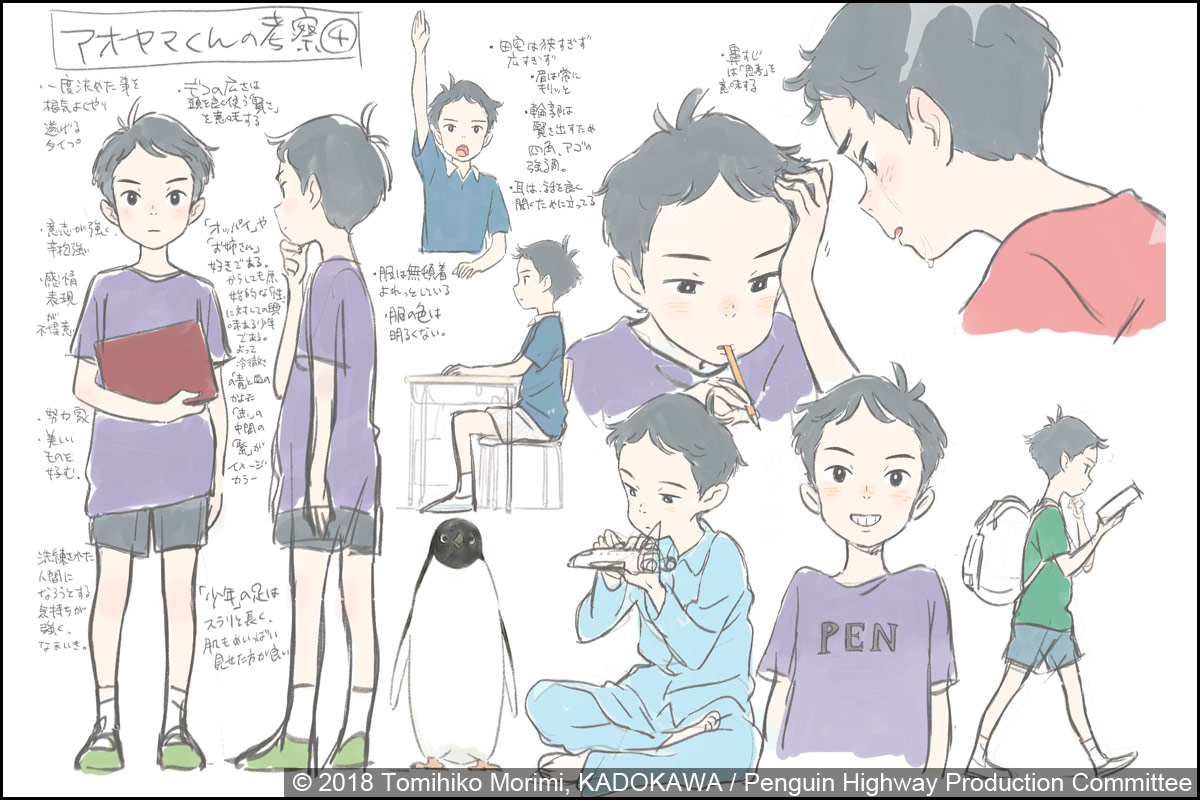

Aoyama was designed as a boy character who looked very gentle in my first proposal. Characters in my past works seemed to affect the design of Aoyama. So, I read up on the original novel again much more carefully and fully reconsidered Aoyama’s design. After that, I gave his design the atmosphere of a rigid child. I showed the second version of the proposal to Mr. Morimi, and he approved the proposal for film adaptation.

HN: What kind of changes did you make to the design of Aoyama back then, specifically?

Hiroyasu Ishida: With Aoyama, I dug into the image of a clever boy and I shifted focus on behaviors, expressions and designs of a boy genius. Among all the changes I did to his design, I think the easiest to notice for you was the sharp eyes I gave him, which was within an inch of “Jitome”*4. Regarding the look of the main character for an animation project that I planned just before Penguin Highway has a gentle atmosphere and an image of a careless and boisterous child. My first version of Aoyama was similar in that design direction. I felt that the image of Aoyama changed to a more judicious boy in my second version of the proposal. I think Mr. Morimi understood the difference because the changes I made to Aoyama were quite clear.

*4: “Jitome” is a Japanese animation industry term for the shape of eyes that looks like it is always staring or glaring at something or someone. It is one of the major designs of eyes in Japanese animation, which is generally for characters who are mysterious, listless, and apathetic or looking down on other people.

The Attractiveness of the Original Story

HN: What attracted you about the original novel? And how did you try to express those attractive points in animation?

Hiroyasu Ishida: It is difficult to pick one thing and say “this caught my heart”, because the original novel has many points of attractiveness. A variety of elements frame the story, such as the main boy character, boyhood, “Onee-san” (the adult woman), encounters with the unknown, and so on. I feel that they make the story as an enigmatic phenomenon, which is a mixture of many different story genres.

When I checked the audiences’ comments about our film, I found that some of the audience had a certain impression of the film that is similar to my impression of the original novel, which was: “I love this film overall, but it is difficult to put into words the reason why this film is good”.

I can simply say, “The main boy character or Onee-san entrances you”, to explain the reason why the original story is fascinating. Actually, that’s how I answered in some interviews. However, now that after quite some time has passed from the theatrical release of the film and seeing the audiences’ reaction to the film to some extent, my analysis is that the indescribable sensibilities of childhood that you experience in your juvenile years, which I also experienced during my childhood but couldn’t put into words because I was a child, were expressed indirectly by a unique way of blending a variety of pieces, which constitutes the film’s story. That is the attractiveness of the original story.

So, when I was developing the structure of the film’s story, I couldn’t omit any elements in the original story easily. It was quite difficult to make the film with a simple story line. Actually, I think I can say that the real goal of this film was not making a simple story.

There are many pieces in the film that center around people’s childhood, and no one’s childhood could be called the definitive childhood experience, so I think that each of the audience can easily find something they can relate to in their own life.

By the way, I’ve heard from a producer that Hidetoshi Nishijima, who was the voice actor of Aoyama’s father, had said, “It is a film where people can find something that they can relate to, something they’ve experienced in their childhood”, after he watched the final film.

If I picked a different novel as an original story for the film project, which enabled me to say the theme of the story simply, like “friendship” or “love”, this interview might’ve proceeded more smoothly (laughs).

Collaboration with Author and Scriptwriter

HN: Did you talk or discuss with the author of the original novel, Mr. Morimi, anything about the content of the film throughout the development process?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Mr. Morimi’s stance on the film was basically leaving everything about the film to me. So, I talked with him a few times about the content of the film, up until the film’s completion.

I met him once when we got the permission to cinematize the novel from him by showing our second proposal. At that time, there was almost no opinion and advice from him to me, but he only gave me his opinion about the vision of Aoyama as a boy genius. On the other hand, I asked him some questions but his replies seemed to be about trying to remember things from the original novel, like “What was that about in my novel?” He is a novelist who releases new titles one after another. For example, when the TV animation series Yojouhan Shinwa Taikei was on the air, he released Penguin Highway. So, I think he is the kind of person who lives in the moment, focusing on the work he is currently writing at that time.

After the meeting, Mr. Morimi gave me no particular requests for the film. I asked him only one question about the story, which is about the part of solving mysteries in the story. His answer to the question was a bit of advice without any clear instruction, “My original story was a bit complicated in that regard, so please feel free to simplify them in the film”, and left it to me.

Mr. Morimi is a man of a few words, so I thought what he gave his opinions on were particularly important points in the story. I took time to find the direction on the vision of Aoyama being a boy genius and how to solve the mysteries in the film’s story. The mystery-solving part relates concomitantly to the journey of the story from the beginning. So, I struggled to think thoroughly about that, and then found a unique answer for the animated feature.

HN: What was it like working with the scriptwriter, Mr. Makoto Ueda?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Mr. Ueda knows well about Mr. Morimi because he did the series composition*5 and scriptwriting for a TV animation series titled Yojouhan Shinwa Taikei (English title: The Tatami Galaxy) based on the novel of the same name written by Mr. Morimi, and he wrote the script for the animated feature Yoru wa Mijikashi Aruke yo Otome (English title: Night Is Short, Walk On Girl), which is also based on a novel by Mr. Morimi.

Here’s a story I’ve heard from Noriko Ozaki, a producer from Fuji TV: Mr. Ueda personally deigned to praise my short film titled rain town and he kindly sent a message to Mr. Morimi: “He is the director of rain town, so he is totally fine”.

Like a matchmaker, he kindly supported building a good relationship between Mr. Morimi and me.

Additionally, Mr. Ueda gave me a lot of helpful and useful advice, like “I think Mr. Morimi surely wants to do this kind of thing here”, even though Penguin Highway is a different type of novel compare to Yojouhan Shinwa Taikei and Yoru wa Mijikashi Aruke yo Otome. After our first meeting in person for Penguin Highway, I had Mr. Ueda come to Tokyo from Kyoto every few weeks for meetings. Outside of those meetings, he also sends me his plots via email many times and I reply to him all my thoughts about his plots, like “I would like to have your idea in this part/scene. On the other hand, in terms of your idea about that part/scene, I’m thinking to direct in this way”.

I had the impression that Mr. Ueda likes to think of ideas of short stories and materials for the side and back stories. He has been trying to suggest me new ideas for the story from his unique distant point-of-view from the original novel while I was developing the structure of the film’s story based on Mr. Morimi’s original story. I felt that he indeed gave a variety of wonderful ideas to me, as much as possible. So, there are quite a few great ideas by him, which I sadly could not use to make the running time of the film within 2 hours.

To cite some of Mr. Ueda’s original ideas, there is a scene where Aoyama’s father turns a bag inside-out in front of Aoyama. That part is a new addition for the film that the original novel doesn’t have, based on an idea Mr. Ueda thought of. Turning that bag inside-out expresses well in the film an abstract concept from the original novel, that the world is being folded and turned inside-out.

When Aoyama takes a note, he organizes information into what looks like a scrapbook by using an index and tags to classify them, which was also Mr. Ueda’s idea. ‘Onee-san’ doing research by herself was another idea he came up with, but we couldn’t use it in the film.

Mr. Ueda not only put many of his original ideas into each of his plots, but also gathered his ideas into collections of ideas that he couldn’t use and felt that it would be good to have for the film as well.

Each plot he sends me, he would kindly attach a collection of ideas at the end. His ideas ended up amassing into a huge amount of information, so I can’t remember them all now (laughs).

*5: It is a role for TV series development in the Japanese animation industry for controlling the structure of the story throughout a series. Generally, an experienced veteran scriptwriter takes charge of this position and designates scriptwriters for a series and manages them by working closely together with the director and producer(s).

HN: You and Mr. Ueda developed the whole script for the film gradually by sharing each other’s ideas and exchanging each other’s opinions every time the script reached a certain volume, I suppose?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Yes. I shared with Mr. Ueda my impressions and opinions about the script he wrote and original ideas he suggested. I would also ask for his opinion when I gave him my new ideas, then he would reflect them into the script. We repeated this workflow over and over.

It was very comfortable to work with Mr. Ueda because he kindly answers to all my questions and requests, whatever they were.

Target Audience

HN: The protagonist of the story is a boy in his fourth year of elementary school, but he is a very intellectual boy who can scientifically deduce as well as adults. Thus, I felt that this is a sci-fi/fantasy story that not only children but adults can enjoy. Did you pay attention to particular age groups such as primary school students or high school students as the target audiences while you were developing the film?

Hiroyasu Ishida: I think I intended to have the perspective from the adults who worked for this project from the beginning. Actually, I thought once that this film would be for young adults, because this is a difficult story.

However, I totally forgot about those things when film production started, and I just cared whether the film will be what genuinely makes me feel comfortable by watching it. I developed the film by imagining as if I was the first audience and asked myself over and over questions like, “Is this what I really wanted to do? Am I truly enjoying this creation? Does it make me laugh? And does this story touch my heart?” Then, I had additionally received opinions from the staff. So in the end, I didn’t consider about the age of the target audience whilst developing the film.

If I may digress from the main topic a bit: When I attended a business meeting to discuss the main theme song for this film, which was written, composed and sung by Hikaru Utada, I was asked by one of the producers at the meeting whether I had a particular age group in mind as the main target audience for the film. I answered, “I am making the film feverishly without any thought on target ages”, and then an experienced producer, who has been working with Ms. Utada for long time, said to me, “I think that is good. That is a better way. Utada’s creative activity is the same. I think it is better for creators to have that kind of creative stance.” His words impressed me.

HN: The film happened to attract both children and adults, despite not having target age groups in your consideration, as you said previously. Could you analyze what choices have you made in directing this film that could have led to such an outcome?

Hiroyasu Ishida: I think this film has both aspects of light and shadow. The animation Studio Colorido created before Penguin Highway are generally stories focusing on the bright side of human society, which is easy for children to understand. And I think that the market expects us to create that kind of animation. But what I thought from the beginning of the Penguin Highway film project is that I want to describe not only light, but shadow. I want to draw a strange, eerie, or scary feeling in this film.

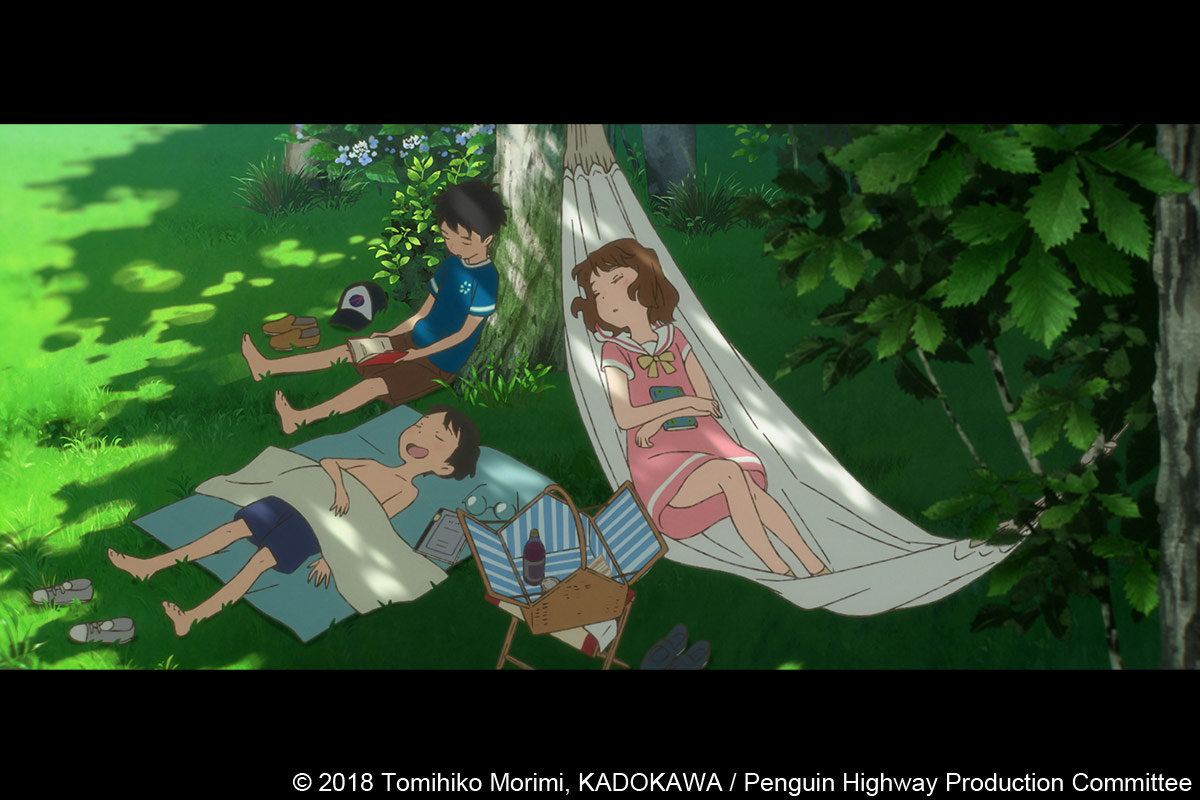

When I remember my childhood, what left the biggest impression on me are experiences that are the combination of two completely opposite emotions, such as things that were fun and not fun, and things that were scary but also made me happy. Actually, one of the reasons why I was attracted to the original story of Penguin Highway is that the story portrays a dark part of childhood. So, I paid attention to the staging of the two extremes in the film, fun things and scary/sad things, for Aoyama.

When I make animation, I always thought that animation is what I need to uncover my true thoughts on something. This time, I naturally thought that I would like to depict both light and shadow in the film, which are the “fun things” and “scary/sad things”. I think it might’ve resulted in making this film have such a large audience.

For example, I think that probably children simply have fun with Aoyama and his classmates’ lively scenes, and adults maybe enjoy the science-fiction part of the story, such as the mysterious creature, “Jabberwock”, or an unknown world, which we call “The Sea”, as the “scary/sad things”. So, that is to say, I was not so conscious about the target audience while we were developing the film.

Designing the Universe

HN: There are some places with fantasy elements in this film, such as a forest, a grass field and a seaside town. The background art of the scenes in those places are really stunning and I felt like the main character and I were experiencing the same emotions, as he has new adventures in new world. I would like to hear the story behind the art direction in designing film’s universe.

Hiroyasu Ishida: Regarding the background art for the scenes of daily life, I intended to describe the feeling of reality as much as possible. For the scenes with fantasy elements at the seaside town, which is called “The World’s End” in the story, the grass field, and “The Sea”, I designed the sceneries and the universe by becoming more imaginative, because those are imaginary places.

Actually, there is no big difference between the final visual design of the grass field and my first design sketch for the grass field in my first project proposal. I designed it before I drew the storyboards. I carried out my original intentions for the universe.

Regarding the design of the forest in the film, it includes some my original creations. I drew some trees that look like white birch, which do not grow in the main island of Japan*6. When I took a trip to the Shiretoko Peninsula in Hokkaido*7, I saw the green there and thought: “That’s nice!”

So, I brought the vegetation from the Shiretoko Peninsula into the forest in this film when I designed the scenery. I also recalled the cold dry wind that blows through the extensive Kushiro Marshland*8 in Hokkaido when I designed the grass field for the film.

*6: The setting of the story is in a town in the Nara Prefecture in the main island of Japan.

*7: The northern prefecture at the second largest island of Japan.

*8: A national park and the biggest marshland in Japan.

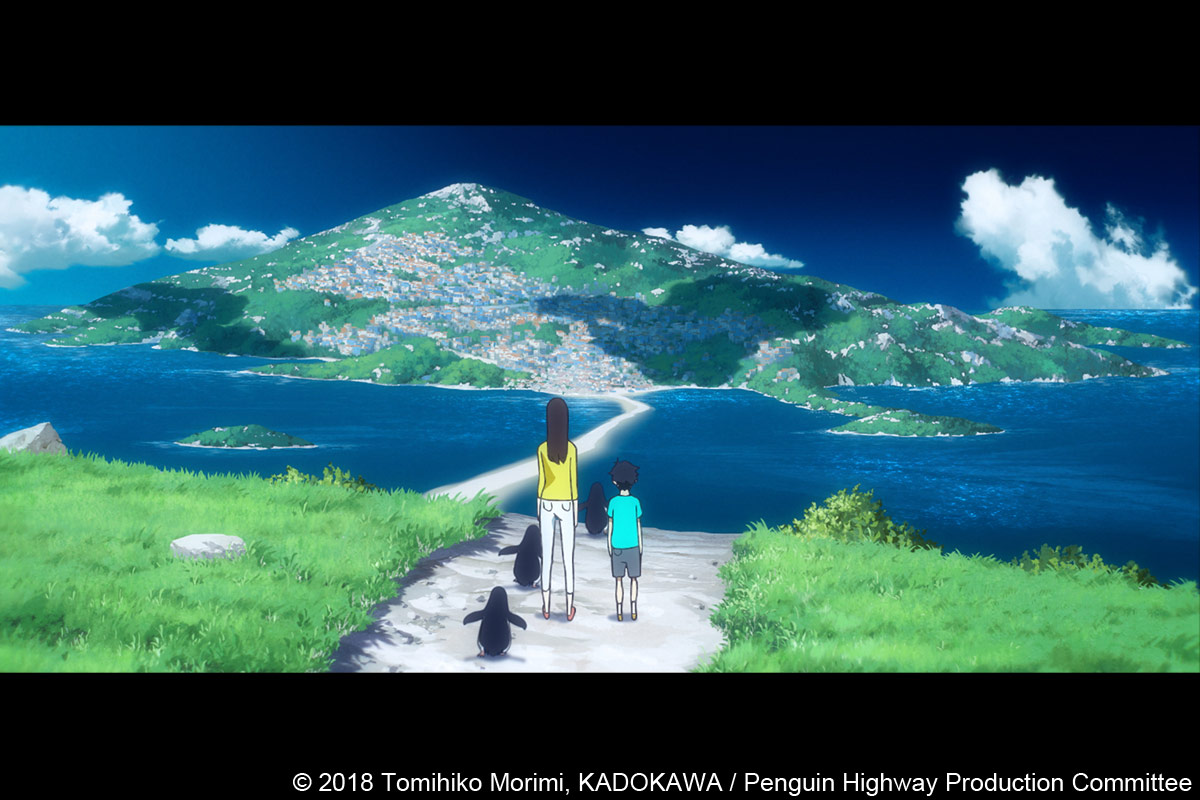

Hiroyasu Ishida: I also put many of my own ideas into the design of the seaside town because I wanted to express a part of the story’s universe that would properly make the audience have feelings of strangeness or fear. It ended up creating a jump in the town’s description in Mr. Ueda’s script from Mr. Morimi’s original story.

What I wanted to express in the scene at the seaside town was that it is like a different world made by someone with a will that is not human, beyond human territory, and we feel the ring-like structure of the world, like the Ouroboros*9. It is kind-of an abstract concept.

I drew the scenery with the feeling that it is a world consisting of different rules compared to our real, human-inhabited world, and the world is barely recognizable as three-dimensional from the vantage point of our real world. Still, you can find several things in the seaside town that are from the town in the real world, where Aoyama lives. I thought a lot about the rules and balance of embedding those ideas into the seaside town when I designed the scenery.

However, if I overdo those complex ideas for the design of the seaside town, the look of the town would be in disorder and chaos. The only source of visual information on the seaside town I could get from the original story was: “It is a foreign townscape”. Hence, I visualized the seaside town based on a view of a particular town, in a particular country, actually, but I intentionally didn’t reveal the name of the town.

*9: An ancient symbol depicting a snake eating its own tail.

Hiroyasu Ishida: I would like to say one more thing about the design of the seaside town: In the film, Aoyama goes through the town, along a river. I designed the river in the seaside town, which flows to a postbox at the center of the public square, to have a connection with the map Aoyama and Uchida made as a part of “Project Amazon” by researching about a river in the suburb they live in.

Music

HN: Could I hear your intentions with the music in the film? If possible, could you please let me know some of your experiences with the creation of the music, such as your collaboration with the composer Umitaro Abe?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Music is one of the very big reasons why I’m making animation. I really love the effects of the expressive style of animation which can be made from the combination of moving images and music. Therefore, I’m very particular about what music I insert into which scene.

I prepared a music list when I asked Mr. Abe to compose music for this film. In the list, I numbered all the pieces of music like M1 and M2, and specified where in the film I want to have that music, such as “Please compose M1 for this scene”, and “Please give me M2 here.” I wrote a subject for each scene where I want music, which simply described what of the story I wanted to express in each scene. I also wrote a lot of concrete information about my requests for each piece of music, such as “The story builds up tension from this shot in this scene and then slows down from this shot”, and “The atmosphere of this shot is similar to the feel of that part of the melody in one of your past tunes.”

He sent me each piece of demo music via email when they were composed. Every time I received them, I stopped drawing to focus on listening to the music thoroughly and considered the balance between the music and the scene in the film. Then, I wrote my honest impressions and opinions about them, such as the good points of the music, and parts of the music that would have better synergy with the animation if he were to arrange them differently.

To share my vision of the music for the film and my intentions to arrange some pieces of demo music with Mr. Ueda via text was more difficult for me compared to explaining my requests to animators about the visual aspects. I carefully chose polite words by making the best possible use of my entire vocabulary when writing texts with my opinions to Mr. Ueda, to avoid any misunderstandings.

Actually, it was the first time for Mr. Ueda to take charge of the soundtrack for a feature film, but still, he composed 46 really fantastic tunes for the film by very kindly accommodating my requests more than I expected. I’m really appreciative for that.

Highlights of the Film

HN: Could you please let us know what you think are the highlights of this film?

Hiroyasu Ishida: It is always on my mind how I would feel if I could watch this film when I was a child, because I think the impression my childhood-self receives from this film is surely the attractive power of this film.

I think if I watched this film as a kid, the lively scenes of the child characters should be the easy-to-understand and fun parts of the film. Also, I would definitely enjoy the scene that I am calling the “Penguin Parade” later on in the film where we’ve animated running penguins, because it will directly connect to a sensibility that is common to children: The more it moves, the much more fun it is.

On the other hand, I think that the light-and-shadow concept of the film, which I’ve talked about before, is another highlight. When I was a child, I watched a cutout animation, which was eerie for children, in a program titled Minna no Uta (English title: Songs for Everyone) on NHK’s*10 education channel. When I was a kid and watching the TV animation series Manga Nippon Mukashi Banashi*11, which was popular among children, sometimes I came across episodes with a scary story. My feeling at that time was not fun, but I still desired to watch them because the forbidden fruit is the sweetest. I remember that it was a feeling of fascination with the unknown.

I think the shadow part of this film is in a similar sense to those animation I watched in my childhood, because I made that part by using all my feelings at that time which I could still remember. So, I think they became scenes that catches children’s eyes, the same way as those scary animation. Hence, this film has the two attractive points that have both extremes, I think.

*10: NHK is Japan’s national public broadcasting organization.

*11: A Japanese animation series (1975 – 1994). It tells about 1,500 old tales from every region of Japan.

HN: Did you hear from Mr. Morimi about the impression he had of this film?

Hiroyasu Ishida: He told me, “You showed me everything what I myself as a child wanted to see through the film.” At the same time, he also said that if he actually watched this film in his childhood, his subsequent life might be different. (laughs)

In terms of the toy vessel Aoyama used for searching “The Sea” that appears at the end of the film, he gave me his comment: “I’m okay with the animated version of Penguin Highway having that ending scene.” I was drawing the storyboards with the pure intention of cheering up Aoyama as much as possible, so it was natural for me to think of adding that shot in the ending scene, and I storyboarded them. So, I was relieved to hear that the scene was okay for Mr. Morimi.

Differences between Directing Short Films and Feature Films

HN: This is your first feature length animated film. In regard to telling a story by animation, what differences do you feel are between short films and feature films?

Hiroyasu Ishida: What I realized after quite a while from the day of its theatrical release in Japan was that what the majority of audience wants to enjoy the most, when they watch an animated feature film, is its story.

Regarding the movement of the animation and the quality of the drawings in this film, there was room for improvement because it was my first time directing a feature length film, and I couldn’t manage them perfectly. But I felt that the ratio of the audience for this film who’ve noticed those kinds of shots in the film and mentioned that “this part of the film is poorly done” was very little. As a whole, I had an impression that there were a much greater portion of the audience who expressed their emotions, like “It was fun or sad or funny”, that they got from their overall impression of the film, including the story, drawings, movement of the characters and music.

Come to think of it, it is obvious that much of the audience for short films tends to watch each film in their own preferred way, unique to them. They check the visual expressions of short films in detail. Of course, the narrative of each short film is also an indispensable checkpoint for them, I understand that.

Anyway, that is the difference I felt between a feature length film and a short film, after I made this film.

HN: You mean that there is a tendency of much of the audience for short films paying more attention to the quality of drawings or visual expressions than the audiences of feature films, and you, as a director, tend to focus more on visual elements when you make a short film, right?

Hiroyasu Ishida: Compared to feature films, I think so. I feel that the differences in the production environment between feature films and short films are affecting the creative stances of each. When I make a short film, I can stick to animating powerful pictures throughout the film with a small creative team. And as its playtime is short, the audience can wholly enjoy the short film’s elaborate visual expressions, which is crammed with information.

However, if I make all shots in a feature film on the same level of elaboration as I do for a short film, the total amount of information the audience receives from the film during its long playtime would become excessive. It ends up making the audience swamped with information from the film.

To start with, I can’t receive enough budget and human resources for a feature film project that would enable me to create each shot on the same level as a short film project. That is to say, when we make a feature film, we should intend to make a film that lets the audience judge by its overall quality, and for that we need to thin out the information in the film by managing the amount of information in each scene well.

To recap, I learned that feature films and short films are not equal on the situations of creators and audiences, and there is a special balance in viewpoint between the creative side and the audience side for feature film production.