Synopsis

Funny and gentle Mr. Link, the very last of his species, yearns for companionship and a place where he belongs. To help find his rumored cousins in the fabled Valley of Shangri-La, he recruits Lionel Frost, the “world’s greatest” sleuth of myths and monsters. Together with courageous adventurer Adelina Fortnight, they embark on a hilarious globe-trotting journey to find Link’s far-flung family.

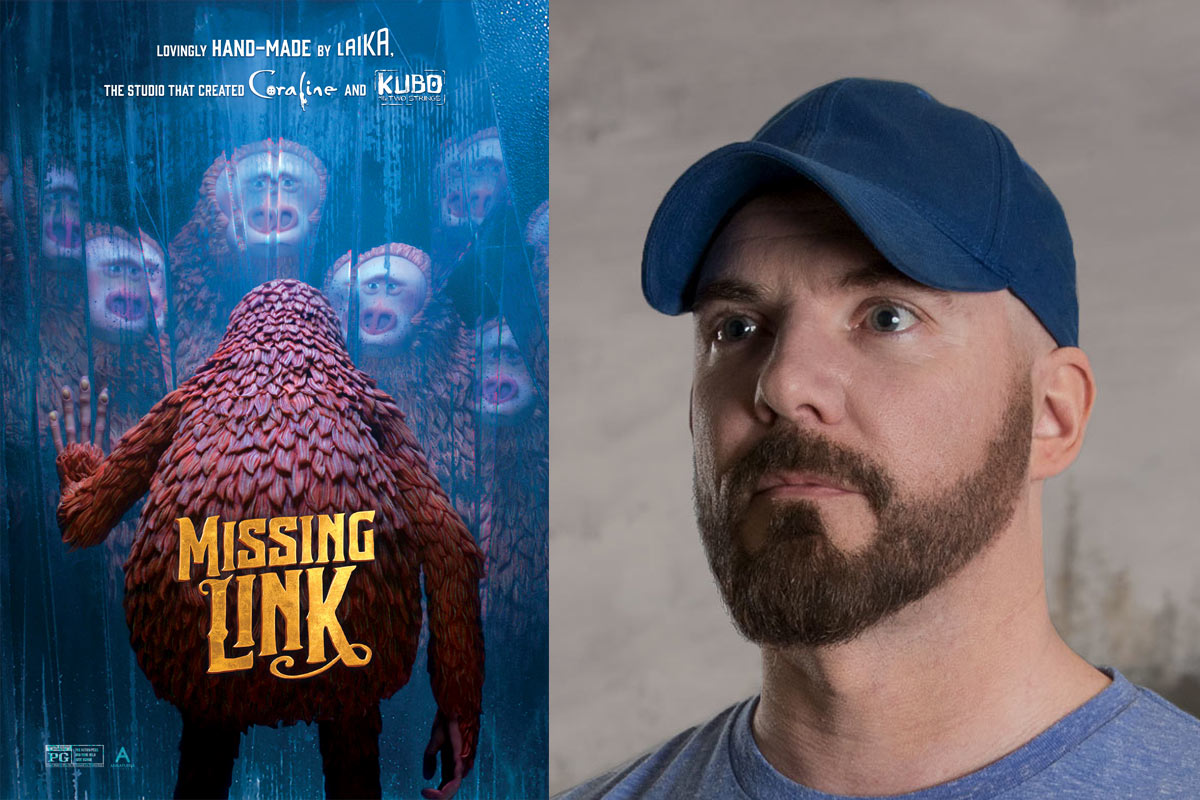

Missing Link is the latest featured film from LAIKA, a multi-award-winning Animation studio recognized as one of leading stop motion animation studios in the world. The film is expected to win many prestigious awards, including Annie Awards, Golden Globe Awards and more, not unlike LAIKA’s previous films.

Missing Link tells the adventurous and funny journey with a band of misfits: Sir Lionel Frost, an explorer and investigator on mythical creatures, Susan Link, a creature discovered by Lionel known to be the missing link, and Adelina, the widow of Lionel’s past partner with a no-nonsense attitude, with rich visuals only made possible by LAIKA’s stop motion technique.

We had an interview with Chris Butler, the director/writer of Missing Link, during his stay in London for the retrospective screening event of LAIKA’s film library, and heard the story behind of the creation of Missing Link in-depth. We are happy to be able to share his insightful words with you.

Interview with Chris Butler

Animationweek (AW): How was the initial idea of the story for Missing Link developed?

Chris Butler: I feel like I get asked that a lot, and I feel like I change it subtly every time! Because the truth is, I started writing it more than 15 years ago and I’m not exactly sure when it first popped into existence, but I’ve got a few notebooks that I’ve had over the years, and there’s probably about 10 ideas in there. That’s all I’ve ever had! 10 ideas and I just keep going back to them, they evolve over time and sometimes I lose interest in one and go on to another and one of them was Missing Link.

The kernel of the idea was I always wanted to do kind of an animated Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981); so, it was like an Indiana Jones and I’ve always been a Sherlock Holmes nut, so I think the idea for this was Sherlock Holmes meets Indiana Jones meets Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987). Originally here was a story that I had about Sir Lionel Frost, who’s the world’s first cryptozoologist, but Link wasn’t in it. I think Sir Lionel was chasing unicorns, weirdly enough. And I had a different idea, which was about a lonely Bigfoot, trying to find his family and I kind of smooshed the ideas together and that was Missing Link.

AW: So, when it came to writing the script, what did you particularly take care of in doing that, and what was your favourite part of the story to work on?

Chris Butler: I knew it was going to be a big adventure story. That was a departure for me in that I’d never really written action before. I’m very much a dialogue writer; I love dialogue. And I think sometimes people are a little critical of that in animation, they feel like animation should be ‘more show, don’t tell’, but I strongly believe that animation is just a medium and you should be able to tell any story in it. If you ask anyone what their favourite movie is, they will probably name a movie that’s got lots of dialogue in it because dialogue is human interaction. Communication. I think that’s what’s most interesting to me.

In the Western world, animation ebbs and flows, but it’s still seen as a kids’ medium, and I think there is this feeling like if characters are too verbose, it’ll go over kids heads or, you know, it’s like we’ve gone five minutes without a fart gag, someone needs to fall over immediately! And even though there’s plenty of fart gags and falling over in this movie, what I find most interesting is the dynamics of human interaction. I was really interested in having a leading character who was pretty unpleasant, egocentric, borderline sociopathic, and that was very much influenced by Sherlock Holmes, who I think is a hugely compelling literary creation, because he is so flawed; he is so unpredictable and unpleasant. He lacks social skills, so if you put him in any situation, it becomes an interesting situation and I wanted that same feeling with Sir Lionel, but it’s a balancing act because you don’t want to turn the audience off. And yes, there are going to be a lot of children watching this, so I don’t want them to be turned off by the main character, but of course I’m helped in this particular story because Link is so genuine and lovable that he is the yin to Sir Lionel’s yang.

AW: Speaking of which, there’s a really lovely synergy between Lionel and Adelina and Link, but what difficulties did you face developing those three main characters and those relationships?

Chris Butler: Sir Lionel and Link developed pretty easily, I’ve got to say, because I think that was the core of the story…

AW: And Link as Susan – that was genius by the way…

Chris Butler: Thanks, that was important to me. Very important, because I talked about this being an action movie, but it was very important to always have something else to say, for family entertainment, to have a theme that has some kind of importance. I don’t want to be didactic and I don’t want to be preachy, but I do believe the best kids entertainment is the stuff that’s challenging and has got something to say. And for this, it was about identity and how your identity is chosen by you and not put upon you by other people. So that Susan joke, and even though it plays as a joke, that’s the meaning, that’s what I really wanted to get across.

I think the trickiest one out of all of them was Adelina because there’s a danger because it is really about these two guys, there’s a danger that if you bring a female character into that, that she might feel side-lined or she might feel like she’s just there to provide a feminine touch and I was loathe for that to happen. What I wanted was for Adelina to provide some hint of a backstory of Sir Lionel because they had a relationship and I thought that could potentially be a good dynamic, but it was also about all these characters going off on this adventure, but they’re looking in the wrong place. They’re all trying to fit into something that they don’t really need to fit into, and that was Adelina’s story too. Zoe Saldana was a great part of that.

We work with some pretty big names, some of them have done a lot of voice acting, some of them have never done it before, and it’s quite daunting, I think, because they’ve got the script, and a booth. That’s it, they don’t have props, they don’t have sets, they don’t have other actors most of the time to act against, so it’s just them on their own. And it’s a very pure form of acting. And I think once they get into it, they all enjoy it, and they’ll read lines in a way that I wasn’t expecting, and that’s when it becomes very exciting to me because it starts to take on a life of its own.

I’m often sitting there, rewriting lines.

AW: Moving onto the action and the camera work, especially during the scenes on the ship, is quite incredible. In terms of storyboarding and shooting stop motion, what was the toughest challenge in accomplishing those scenes? Am I taking you back to a dark place?

Chris Butler: The whole thing was tricky! I didn’t suffer as much as the animators did, let’s put it that way, because all that ship movement was done with the camera, rather than the set. We didn’t move any sets. So, when Sir Lionel was running on the wall or when any character is off balance, the animator is entirely creating that on a still set, which is mind blowing. They devised a template system so that they would know where the horizon was but even so, you’re frame-by-frame emulating imbalance on something that’s not moving, and I think they did a fantastic job. They created this really dynamic and rich, kind of like a camera movement script. And the way stop motion works, you will do a camera test for a shot first, and I’ll see that in the edit, and I’ll give notes long before you animate.

So, we constructed a rhythm of movement through the whole scene. We did storyboard it to death. Because for me, that’s where I’m most comfortable, coming from storyboarding and because you don’t get anything for free in animation, you have to know exactly what you’re doing. You don’t get coverage. You don’t get to move the camera mid shot because it’s not working. You storyboard exactly as you want it, so you’ll know exactly what you’re shooting. And you make the movie several times; the first time you make it, it’s all storyboards. A big action sequence like that was a big thing to take on. I was very influenced by early Steven Spielberg action sequences where there’s a real narrative to it. There’s a beginning, middle and end, and comedic beats and dramatic beats like Indiana Jones. You have to meticulously plan every beat of that.

AW: The environments were amazing as well, such as the Yeti’s temple in the Himalayas, can you talk a bit about the story behind the design of the film’s universe and especially the background art?

Chris Butler: I come from a background of design, so I had very specific ideas of what I wanted to create in this movie. I think a lot of that came off the back of finishing ParaNorman (2014) and wanting to do something that was just visually very different. What’s exciting to me about the studio (LAIKA) is that we don’t have a house style. Every movie is supposed to look different from the one that came before, so when you start one of these things, you can go anywhere.

At the very, very start, I put together a look book, where I’d pull images that I found interesting. And that’s what I would take to the production designer and have those initial first conversations. My look book was made up of National Geographic photos, it was drawings done for 101 Dalmatians, the Disney film, by Ken Anderson, drawings done by one of my favourite artists, Warwick Johnson Cadwell, and some of the art direction from The Thief and the Cobbler, and illustrations from the art director of The Thief and the Cobbler, Eric Le Cain. A big thing for me on this was symmetry and patterning. Symmetry, because ParaNorman was so asymmetric that I wanted to do the opposite, and patterning because I felt emboldened by what we’ve done before, and I wanted a lot of look. In the past, I tried to kind of go for something maybe a little more sparse, less cluttered, but I wanted to clutter, and I wanted pattern on pattern on pattern, I wanted dense patterning. The Victorians themselves went nuts about pattern; wallpapers, bricks, tiles. We have this tendency to think of Victorians as black and white, and you know this Jack the Ripper fog, but the truth is that they loved rich colour. They loved ostentation, and so I wanted to get into that as well.

Nelson Lowry, the production designer, and I would sit down and just really talk about those influences and then it’s his job to try and make sense of it all. And I think he leapt at the opportunity to do something that was radically different from what we’ve done at the studio before. And I think that is the colour aspect of it. Because even though all our movies are different, they tended to be darker. And I don’t mean necessarily tone, although that’s true, but just palette wise. ParaNorman takes place at night. Kubo and the Two Strings (2016) takes place a lot at night. The Boxtrolls (2014) takes place under the ground, you know, there’s a lot of dark and I wanted to step out the shadows and into the light and when I pitched this to the heads of department, I think I said I wanted it to be a kaleidoscopic travelogue; what we’re aiming for is if David Lean made Around the World in 80 Days, starring Laurel and Hardy.

AW: And just on that, I think LAIKA continues to raise the bar in the visual quality of stop motion. Were there any new technical challenges that went into making this film?

Chris Butler: I think probably the biggest challenge was just the scale of it. Definitely the most ambitious thing we’ve ever done. Just in terms of the story alone, we don’t really return to many locations in the plot, they’re travelling around the world. And all those locations have to be built from scratch, and I really went for it in the script, and nobody stopped me! As an example, at the start of the journey, the character dynamics, these characters are not getting along. They are butting heads. And so, I wanted the mise-en-scène to reflect that in that they are literally on shaky ground.

So, a lot of their conversations are on a ship that’s moving, or on a stagecoach that’s rattling. I’m very impressed with myself, I’m like, ‘oh, look at me and my mise-en-scène!’ And then someone’s actually got to build the thing. I wanted tassels on the interior of the coach, and they all had to move, and they did that. And then counter to that, when the characters start to come together as a group, I could have set that conversation in a room, but instead I wanted it to be the most beautiful backdrop for this conversation so I put them on the back of an elephant in the Indian jungle. And again, nobody stopped me!

I think it’s your responsibility as a director in this medium, I think you should, we should be able to tell any kind of story, but I still think it’s your responsibility if you work in animation to take advantage of the medium. And that means things should be larger than life. We did do a few things that we hadn’t done before, such as with the facial animation. Previously, we’ve used a kit system where you create, thousands of shapes, and they exist in a library. And when you’re piecing together a performance, you are using effects from here, followed by a face from there, and you piece it together like a little jigsaw puzzle, and that served us really well. But I wanted the acting on this movie to go up a notch. I wanted a kind of sophistication and nuance to the facial performances that we haven’t achieved yet. And that meant every single one of our shots was bespoke. We threw away the kit system. Every single shot in this movie is a unique piece of animation. So, every set of faces is unique to that shot, and it’s 107,000 faces in the end. Again, ridiculous!

Another thing that we did that we’ve never done before was we used miniature puppets. I mean, I know everything is miniature, but some of the wide shots in the ice bridge sequence we had RP engineered miniature replicas, completely animatable of the characters hanging from the rope. We’ve never been able to do that before because the technology has not allowed us to create such detailed characters. Before they wouldn’t hold up on the big screen, but this was the first time we were able to do it and I think they fit in seamlessly you wouldn’t be able to spot in the movie that we’ve gone from a 13 inch puppet to a two inch puppet, you know? So, there’s a lot of stuff like that.

AW: And what was it like to work with Carter Burwell, the composer?

Chris Butler: He is one of my favourite composers, and every time I get to do one of these things I go to my list of favourites because why not? It was interesting because he wasn’t necessarily a natural choice for this kind of movie. He’d done animation before, with Anomalisa (2015), but for an action adventure movie, he was probably not the first choice for most people. And that’s kind of why I wanted him to do it. Because I’m always trying to think if LAIKA is going to do a big, bold adventure score, how can we make it different? And you get someone like Carter Burwell, and even he said it was a challenge for him because that’s not a world that he lives in, but his version of that is so beautiful. It was a real thrill to witness him at work and in the recording studio at Abbey Road so what’s not to like?

AW: You’ve just been nominated for Best Motion Picture – Animated, at the 2020 Golden Globes, alongside the likes of Frozen 2 and How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World. What does that nomination mean to you?

Chris Butler: Oh, it’s brilliant. I am thrilled. I think when you first start on one of these projects, you know, it takes five years to make and you’re not thinking at all about award season for publicity or release even, you are just thinking about making the movie. It’s a real honour, I think, to be acknowledged by your peers, particularly because the movie did well critically, but not in terms of box office, and I think what this gives us is renewed attention. And I think it’s an acknowledgement that we did something special, so it means a lot and I’m absolutely honoured.