Synopsis

Revolving around a ten-year-old boy nicknamed Courgette, who is taken to live in an orphanage following his mother’s death, the movie tells the story of how he will overcome the obstacles and fit into this new environment, surrounded by a small group of children who, just like him, have been scarred by life.

Film credit

Director: Claude Barras

Scriptwriters: Céline Sciamma, Germano Zullo, Claude Barras, and Morgan Navarro

Producers: Pauline Gygax and Max Karli (Rita Productions, Switzerland), and Armelle Glorennec (Blue Spirit Productions, France), and Marc Bonny (Gebeka Films, France)

Music: Sophie Hunger

Technique: Stop-motion

Running time: 65′

Why can My Life as a Courgette grab the hearts of an amazing amount of people?

My Life as a Courgette is the animated film in which I sympathized with the characters and I was touched by the most in 2016. I believe that you would be pleasantly surprised by how much you can understand and share the emotions of the children in the film.

I think that the first reason for this is that this film is spoken from the point of view of orphans themselves, not from adults or a third person, which enable us to feel exactly what the children are feeling. It successfully depicts the various emotions of children: innocence, pure-heartedness, naïvety, generosity, and justice. We can immerse ourselves into the world of a story by being deeply connected with the characters.

Secondly, the visual is an essential aspect which contributes to captivating the audience. At first, you may find its visuals to be a bit offbeat but, in the end, you will be feeling a deep love towards every character, including their appearances. Every aspect of this film is carefully designed and well matched to the story.

I talked to the director, Claude Barras, and Elie Chapuis, one of the animators.

Interview with Claude Barras and Elie Chapuis

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Could you please share with us about your journey in the animation industry? How did you start with stop-motion animation?

Claude Barras: I started as an illustrator. Then, I met very determined people. First is Georges Schwizgebel, who has been making films by animated painting and it gave me the idea to go from illustration to moving images. Then I met Cedric Louis, with whom I co-directed 5 short films. And then there were the brothers Frédéric Guillaume and Samuel Guillaume, who were doing stop-motion animation in Switzerland. I was hired by them to do the modeling of the characters of their feature film Max & Co.

Elie Chapuis: That’s where I met Claude. I was an animator in Max & Co, and then we were together until My Life as a Courgette.

HN: What part of stop-motion animation attracted you the most to use that to officially tell those stories?

Claude Barras: I think that, compared to other animation techniques, stop-motion animation is something that is more science-fiction. It is a mix between animation and live-action film, because we really have a relationship to the real world. You have a direct grasp of reality through real objects like the puppets and the sets.

Stop-motion animating has 2 meanings, moving the real objects frame-by-frame, and giving them life. And you have a nearly magical relationship with them.

Elie Chapuis: That magical relationship is the reason why I’m a puppet animator.

Claude Barras: My role is a mediator between staff and puppets to have them meet and have magical relationships. We manufacture everything. There is the fabrication as the main step of the making, which is very important and tactile. Then there is the framing that you do with the camera, you choose your frame like you do in live-action and lighting. And there is all the animation processes, which you do per hands. It is a real process. If we want, we can develop animations as animators.

HN: How did you encounter the original story of My Life as a Courgette? How and why did you decide to make a featured film with that story?

Claude Barras: All my previous short films deal with childhood and all scenarios of them were written by Cédric Louis. He introduced me to a book titled Autobiography of a Courgette, its a slightly different title from my film, and the book deals with the same theme of childhood and everything. And I decided to make a featured film based on the book.

HN: I could feel deep empathy with each character in My Life as a Courgette because all the children in the film feels very real with really characteristic personalities. What kind of research did you do to make their conversations and actions real and emotional?

Claude Barras: I think that in the book, all the characters and the personalities of the children are already very strong. And in the process of making the puppets of them, I first did design sketches of each character with his style for the film so that each kid has a unique appearance with a very big head and very simple shapes like round shapes, triangle shapes, square shapes… That was the beginning of the process.

In the voice work, I was paying very much attention to the relationships between every character and how they interact together. I managed as a group rather than separate personalities. And after the animation process, the animators worked a lot on the recorded voice acting by being inspired by them, because we have very good voices thanks to great actors. This was the step in how every animator had well developed a personal relationship to the character and it helped us to push all the emotions of the characters forward. It’s even more of the existing intention of all characters I had.

Elie Chapuis: If you want, we can add some details about the work on the animation.

HN: Yes, please.

Elie Chapuis: We had a great animation supervisor Kim Keukeleire, and she really helped to translate Claude’s intentions into animation. Thanks to her, we, animators, had really close contact with Claude during the whole process. I think that she managed to find, in the very early stage, what goes well with each character’s personality, in terms of movement, position, emotion, and Claude’s intention of direction, so that she always helped us and reminded us what goes well with the characters.

As an animator for an animated feature film, you work so many times with the same puppet, with the same character. So, through the months of the shooting, you really tend to develop something personal with the character. I mean, at the beginning, you don’t know him or her, but at the end of the shoot, you know everything of the puppet. And there might be a character you really love especially as an animator rather than other characters. You really develop a quite special and emotional relationship with the character, the puppet. You can touch the puppet, the skeleton and body by heart. The puppet starts to act more and more what you really want for the animation.

HN: OK, that is one of the reasons why the characters in the film touch us so much. The animators could understand the characters deeply and connect with them with heart through the shooting.

Elie Chapuis: Absolutely. And Claude was always giving us very precious psychological and very sensitive information about the scene that we were working on. And he always told us, “He/She is more like this or like that”, and that would give us the information on what we do, something that goes with the character.

Claude Barras: I had all the film in my head all the time because I worked many years on it before we shot it. And I had every specific moment in my head very clearly because I did the whole storyboard at first. So I transmitted all the information of that to Kim Keukeleire, the chief animator. For example, I could tell Kim, “Yes, the character is sad in this scene, but don’t forget that in two or three scenes later, there is a nice moment for everything” so I could always define not only a very precise moment in the character’s life, but also in the whole film at the same time.

Elie Chapuis: Claude would rather define mood and feelings of characters than specific details, poses, and more precise things, which Kim worked for. And Kim would translate what he told into very specific technical and more defined things for everyone.

HN: How did you develop all the appearances of each character and the universe of the film?

Claude Barras: Making a stop-motion animation is really a collective work, and I’m a little guardian of the project, but after I relied heavily on the heads of post, the chief designer, the chief painter, the chief operator and the animator, who relies on everyone on the team, I think that the universe emerges from each person little by little. So I didn’t impose everything on everyone, but wanted to have a big room for everyone, from the head to all crew in each department, to express themselves for the universe of the film. So I talked them about my ideas of visuals, feelings, and emotions of the film as the vision of a path to bring their creations through. Then, all the staff worked to the direction with having their responsibility for their specialties.

HN: After understanding Claude’s intention of direction, all staff could add their new ideas by using their expertise and Claude made the best use of them to build the universe of the film, isn’t it?

Elie Chapuis: Yes, they discussed with Claude about all their idea to fit his vision. Claude was very open to any ideas that would fit his vision.

Claude Barras: Before the construction of everything, you already have the storyboard, which gives you a very strong frame of the whole project.

HN: I felt that not only in My Life as a Courgette but also in Sainte-Barbe, your short film, I could share each character’s emotion with their eyes, expressions and acting. What do you think is the reason why your puppet animation can directly touch the audience’s heart?

Claude Barras: Puppets for my film have big heads and big eyes, always, and it is really important for me because head and eyes are like doors to the characters’ emotions. If there are big doors, the audience could see their emotions very well. That allows me, as a director, to film the characters at the closest to their own emotions. I think Elie can explain more.

Elie Chapuis: I think that once again, Kim, the head of the animation, gave us a lot of advice on how to use their eyes and the blinks and the eyebrows and so on. Everything was very well planned ahead. Claude had a lot of ideas that was already tested in the pilot of the film in 2009. It was a one minute short film in which we presented the characters of Courgette and gave us the opportunity to get funding to develop the film. Claude tried to test all his ideas for puppet animation back in 2009 to develop it much further for the feature film. All facial parts on their head are magnetic and it makes it very easy for us to animate their eyes. I think usually in stop-motion, puppet’s eyes are small because in our face, eyes are small so that pupils and their eyes are very difficult to animate and it takes a lot of time because they are very small and difficult to handle. From the very beginning of the film project, Claude and Kim discussed that creating expressions for the pupils need to be easy and shouldn’t be a pain. I think that worked because we, animators, could animate the puppets more directly and create the characters easily.

Claude Barras: I think it also facilitates the meeting with the puppet.

Elie Chapuis: Yes, that is true, we were talking about how the animators meet the puppet and how we get to know the puppet more and more. Of course, a puppet with a big head and big eyes is very easy to use for me. It was much easier and much faster to animate the puppet.

Claude Barras: It also helped the relationship between the puppet and the animator.

Elie Chapuis: Yes, this is a nice relationship, that’s true. Sometimes you are, as an animator, angry at the puppet just because it was not well designed and it is hard to use. And you know you are angry at the puppet. But it was not the case with My Life as a Courgette, it was always a pleasure to animate, because it was easy and it was very handful.

HN: We would like to hear more about the film on the technical aspects. How did you make the puppets and what kind of material did you use?

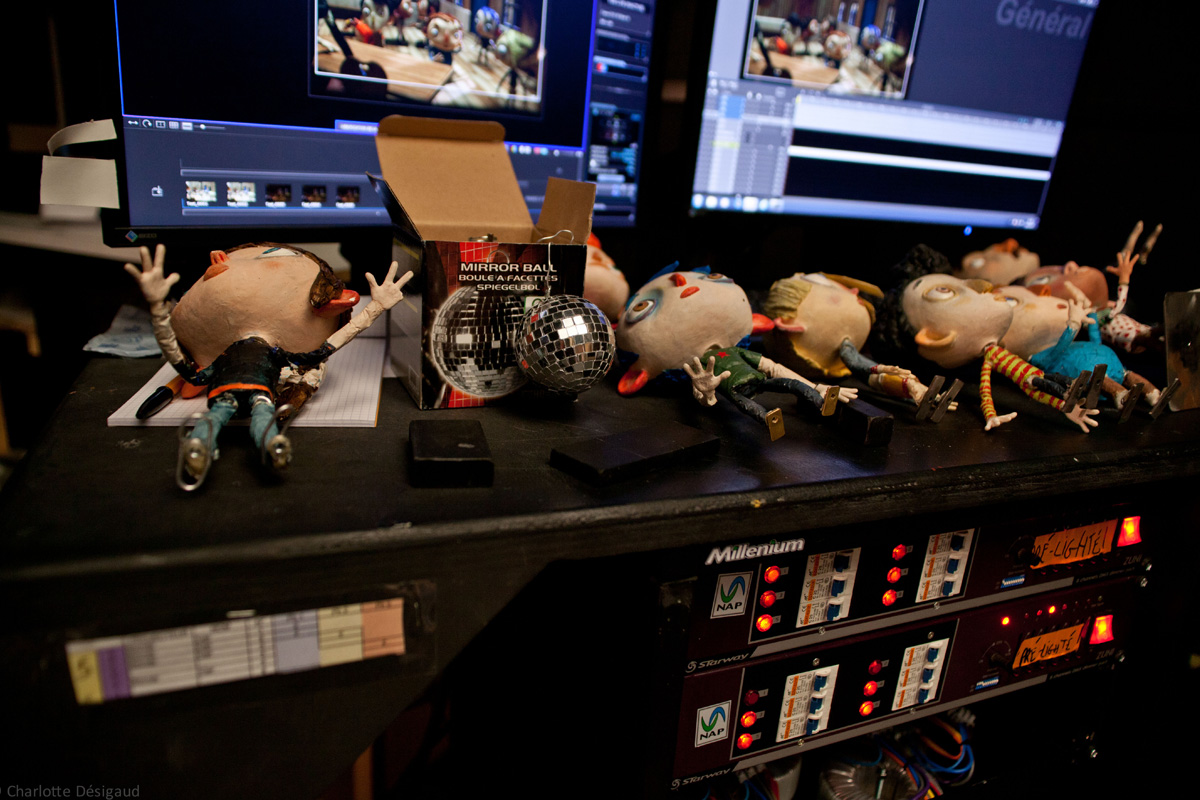

Claude Barras: I think that the puppets of the children are about 20-22cm, and the puppets of the adult characters are around 40cm. One of the difficulties in making them was the weight of the heads. To solve the issue, we started to make the sculptures of their heads and did a 3D scan of them. Then we printed them with a 3D printer by using very light resin. So, the heads are very light and we put magnetic parts inside the heads: the eyebrows zone, the eye contour zone, and the mouth zone. We can make every expression with the eyebrows, eyelids, and the mouth by replacing each facial part and changing its position on the magnetic zone.

And another important thing for puppets is that the design is a bit simple and a little classic. For that, we did a lot of research on materials, what can be used for the clothes and all the skin elements, the arms, the head (which is not the same material as the skin for the arm) and the hair. We chose different materials for each of them and it helped us a lot in giving a quite realistic look to the puppets, even though the design of them is not at all realistic because of their big heads.

Elie Chapuis: The skeleton is made of different types of metal. Then there is foam latex, a material which gives the very rough shape of the different parts of the body. And then, there are all the clothes. All the costumes were made of different types of fabrics. There was a lot of research for the clothes. The arms were made with animation wire inside, a very bendable wire that never breaks, and it was covered with very soft and matte silicon, which is very good skin imitation. The heads with the 3D resin were painted thickly to give the style of what Claude wanted. The hair was made separately with dyed latex foam. It was not painted. It was dyed.

HN: What kind of things did you take care of in putting the puppet in action in front of the camera?

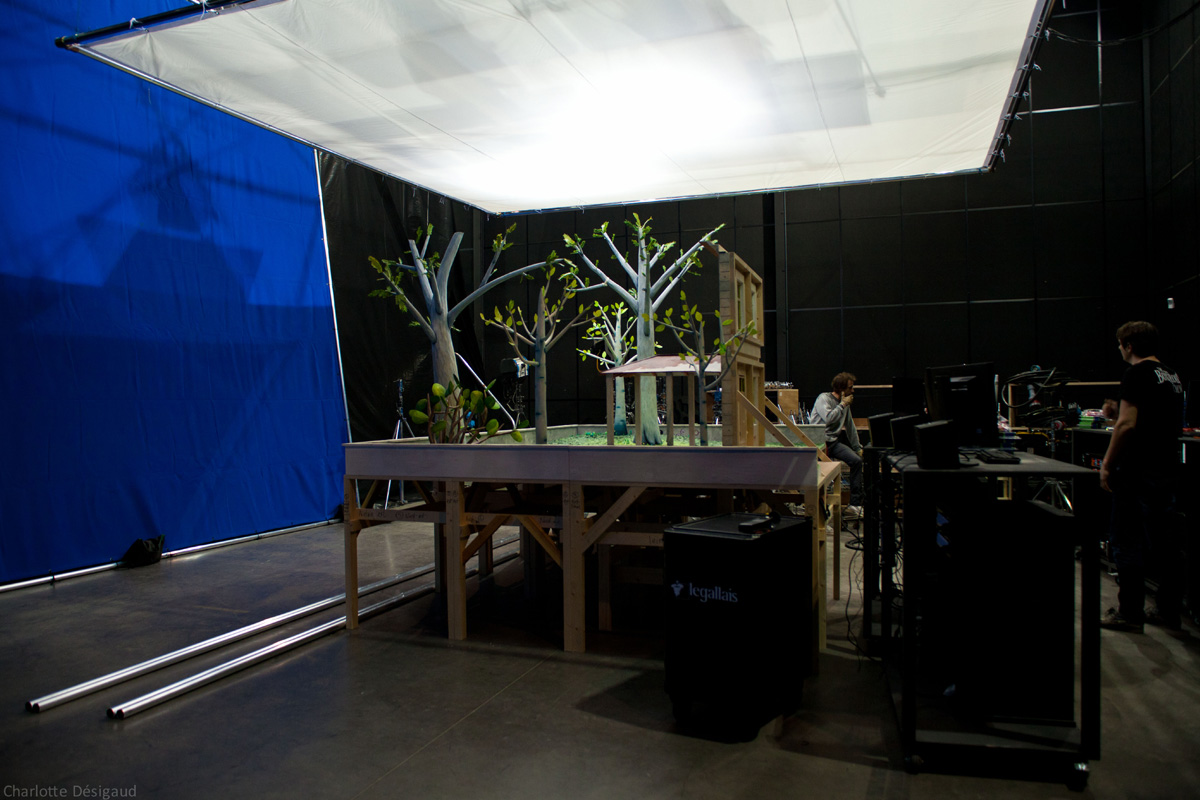

Elie Chapuis: These are two different things. Of course, we all work together, but all the camera work, and the acting with the puppet, are separate moments in the shooting.

The first step is, the lighting is prepared and installed by the camera crew, and they decide to place the camera according to the storyboard. Then Claude comes and checks them. I remember there were quite a lot of discussions in having the lighting to his liking and getting the camera angle he wants. Once everything is ready, everything is glued to the ground so that it doesn’t move and the animators come and prepare the puppets. And we, animators, discuss a lot with Claude and the chief animator. When everything is very clear about what the animator needs to do, the animator is left alone and animates the puppet. After the shooting, Claude, the chief animator and the director in photography, come back and check the finished shot.

These are the different steps in making one shot. So I concentrated on character animation and I think Claude took a lot of care in framing because he is very sensitive about that aspect.

HN: What sort of difficulties did you meet in the production process?

Claude Barras: The hardest thing was to share the time. Time goes very, very fast on a shooting. As Elie explained, there were different steps in preparing a shot and all the steps took a lot of time. You don’t need to rush all the steps, but the time for shooting is limited. You have to shoot a whole scene for the film in a certain amount of months. So you need to share the time among all the crews. Stop-motion is a very expensive technique, but we had a pretty low budget and didn’t have a lot of time for development, so we had to find a good balance in sharing the limited development time. For example, if you squeezed the camera crew to be ready sooner, but not by too much, but the animator cannot start the shot if the light is not really ready. It makes you have to start all over again. So I think the hardest thing in general was time sharing among the whole staff to find a balance of their tasks.

HN: You mean, you couldn’t have many retakes, right?

Claude Barras: No, we couldn’t. We do very quick rehearsals and iterations in shooting stop-motion animation, and we call them “blocking”. These are generally done in very short time, it only takes a few hours for a whole shot, even if it is very a long shot. But the specificity of my direction is that I like to take time for that. If it is 30 seconds of dialogue, I use 5 to 10 days to shoot the 30 or 40 second sequence easily. So, a re-shoot of one shot takes 10 days. A re-shoot brings catastrophe for the production because it makes a 2 weeks delay, and for one shooting it needs a lot of preparation.

HN: Did you do something special for the film, which you haven’t done before?

Claude Barras: I think maybe we didn’t try or learn anything new or completely different from all the other stop-motion films. I think the fundamental technique of stop-motion is the same, but every film has its style of visual, so that every film has a different way of using stop-motion. Even if we know stop-motion very well, I think we discover it again on every film. So my answer is not about making stop-motion new, but it is about how we adapted stop-motion to our film My Life as a Courgette. I think that it is the big thing.

HN: How did you work with the composer to have the best music for your film?

Claude Barras: Sophia Hunger is the composer of the whole film. In terms of the music for the film, I firstly decided the music of the end credits, which starts after a kite is removed. I chose one of her songs for that, which she composed years ago because I thought that the lyrics and the mood of the song work very well with that specific moment of the film. Then our producer suggested me to contact her to know whether she would agree to compose the rest of the music for the film.

When we contacted Sophia, we were at the middle of the shooting of the film, so we sent her a rough edit of the film, which included a bit of the storyboard, half of it being definitive images and shooting images, and the actual images for the film. She said okay immediately and sent us rough music that she had composed. I directly put them in the rough edit of the film as we were still shooting it. After the shooting was over, I spent 3 weeks in Berlin to work on the music with her. She finished the composition of the music for the film and we recorded the music with musicians in Berlin. It was very quick.

HN: What is your favorite part of the story and visuals of the film?

Claude Barras: I think it’s the time in the boys’ room, in the dormitory. The moment when Courgette and Simon say more-or-less “goodbye”, and when Simon passes from a feeling of violence against Courgette. For me, it’s really the key moment in the film where Simon becomes the real hero. There is a transformation in Simon and that is a turning point. I always had a really special relationship with the character of Simon.

HN: Do you have any films, animations or other forms which influenced you?

Claude Barras: Yes, the first, a French film Les Quatre Cents Coups, by François Truffaut, with Jean-Pierre Léaud as a young actor. Then Creature Comforts, the short film series by Nick Park, which plays with the difference between the image and the realism of the sound recording, inspired My Life as a Courgette. Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, the fact that the stop-motion is used really for everything in the film. And in terms of the design of the puppets, Jiří Trnka’s films influenced me a lot. And then two French directors, Catherine Buffat and Jean-Luc Gréco. They have a very original visual style and narrative universe that influenced me a lot.