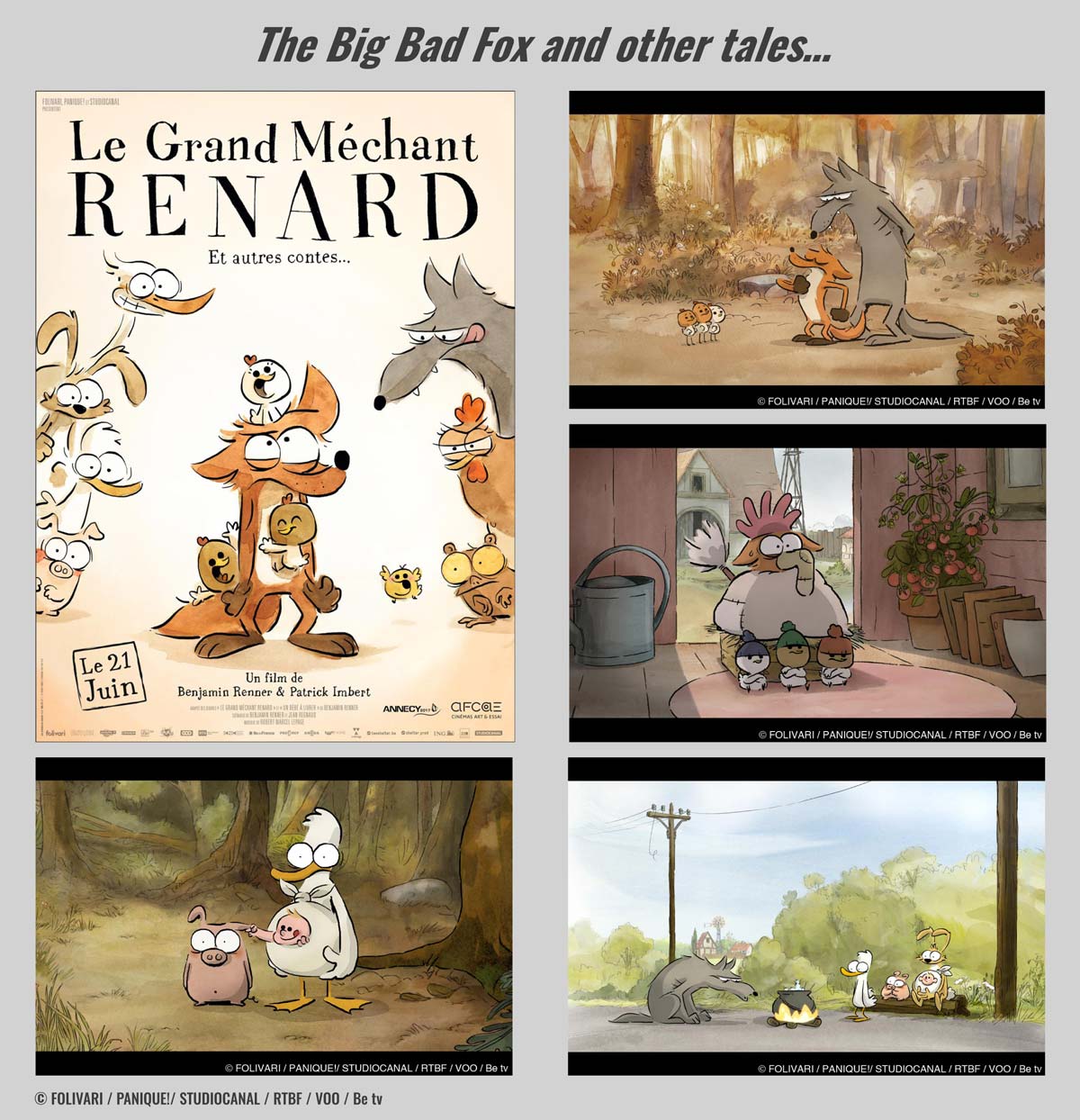

Didier Brunner is the founder of the Folivari animation studio, and a successful producer, who cultivated and led the French animation industry for decades by producing many masterpieces. His latest production is The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales... He told us that every animation project starts with love and passion for the story and creator. This special interview article covers the story behind his great works. Benjamin Renner will also be joining us to talk about his creative journey with Ernest and Celestine and The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales… as a director.

1. Interview with Didier Brunner

Didier Brunner

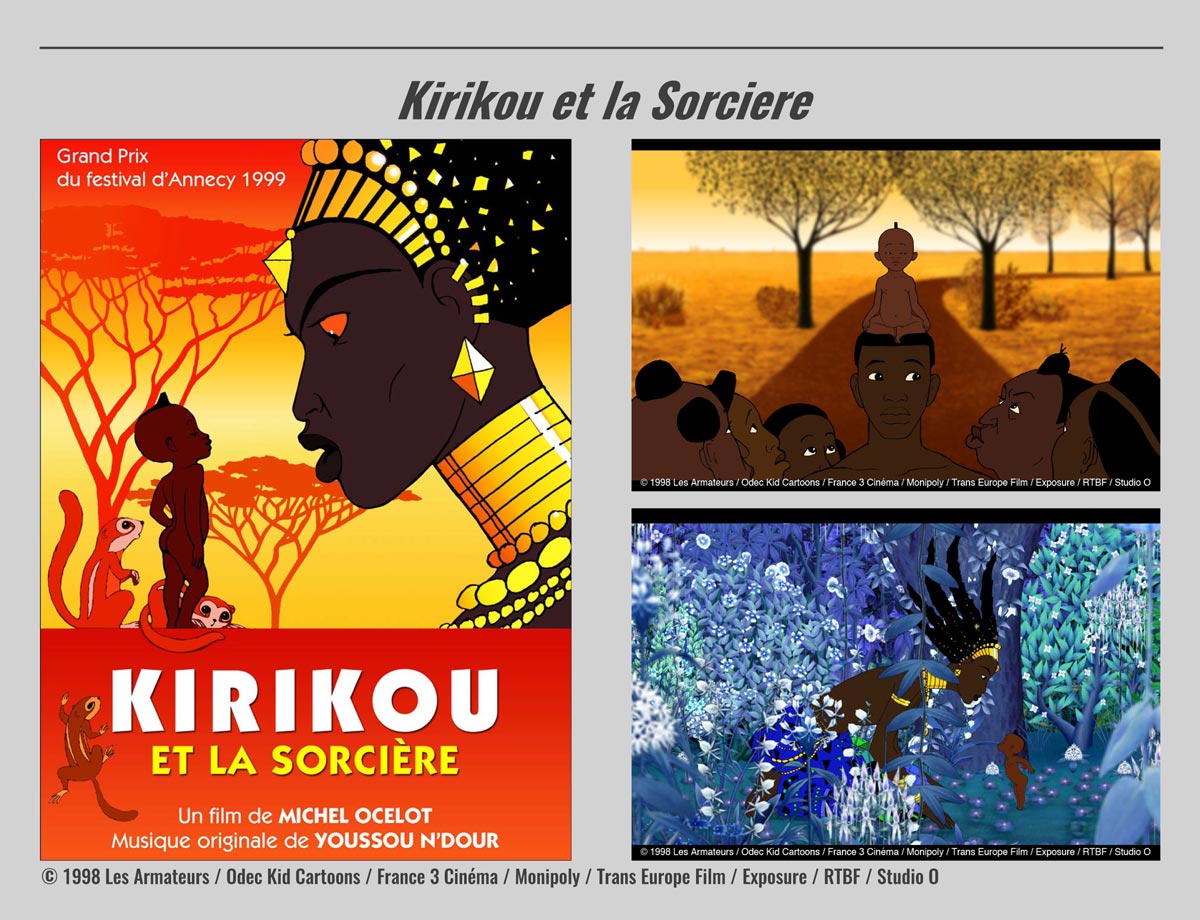

From 1987 to 2013, Brunner introduced and produced a number of major animated features such as Kirikou et la Sorcière, The Triplets of Belleville and Ernest and Celestine, while developing animated series for television. In 2014, Didier Brunner sold his former animation studio Les Armateurs and created his family company, Folivari.

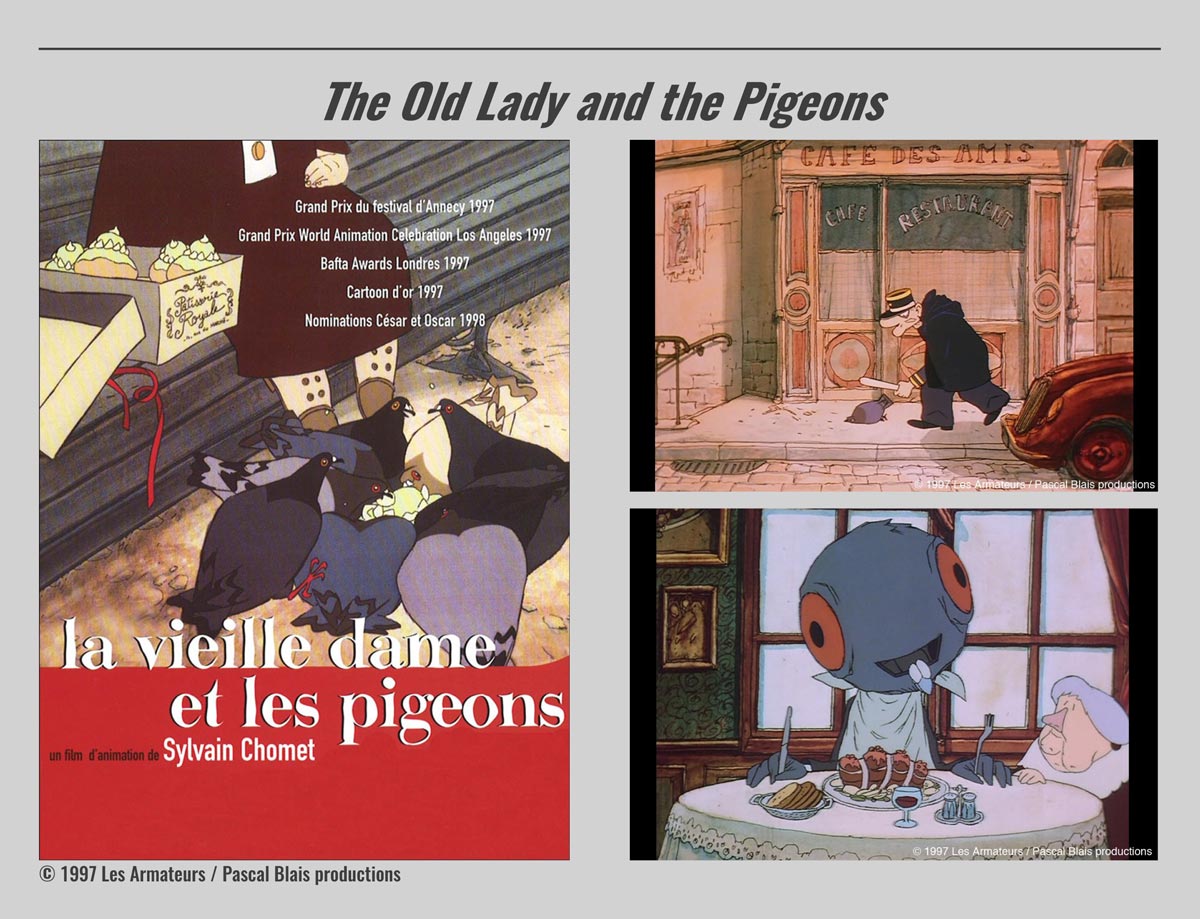

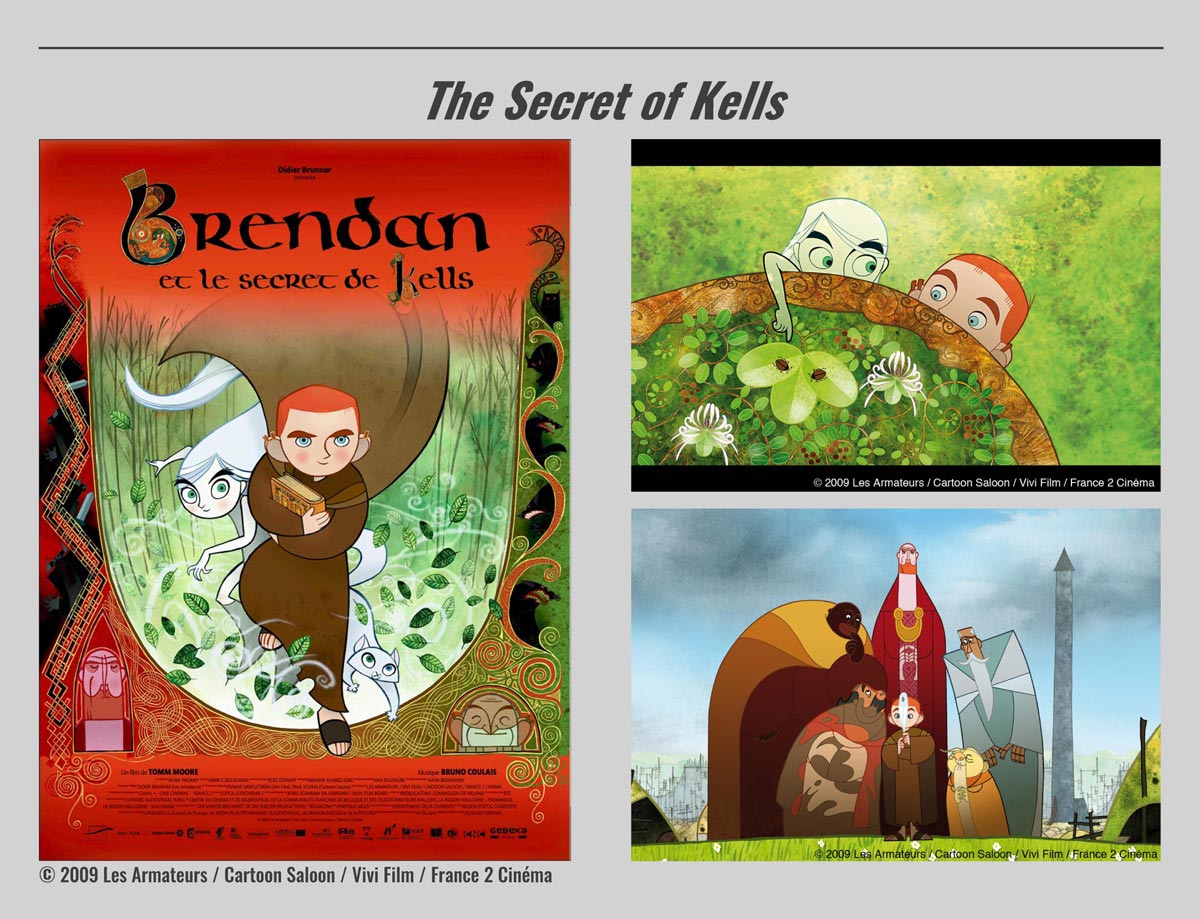

Didier Brunner is a four-time Oscar nominee, for four different films: The Old Lady and the Pigeons, The Triplets of Belleville, The Secret of Kells, and Ernest and Celestine. He has won prestigious awards on several occasions. He received the César Award for Ernest and Celestine and won the award for best European producer at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival. He also received the Winsor McCay Award at the American Annie Awards, for his lifetime achievement.

Starting a career in animation

Brunner recalls the beginning of his career in animation as “an accident of life”. He says, “Before I came to the animation world, I was an Assistant Director and Director of commentaries and live-action educational films.” His first animation project starts from his adoration of the sketchbook on cats from Théophile Steinlen, the famous French artist. It was two-minutes x 26 episodes for La Sept, which became a TV network, ARTE, later. Brunner says, “I asked talented animators and an animation director to make their interpretation of each sketch.”

Encounters with Michel Ocelot and Sylvain Chomet

Brunner got an opportunity to attend the Annecy International Animated Film Festival with his first animation project, where he meets Michel Ocelot and Sylvain Chomet. “I discovered the Ciné si short silhouette animations show, including Le Manteau de la Vieille Dame and Princes et Princesses.

Brunner remarks, “All those old and very charming silhouette animation films from Michel suddenly gave me the crazy idea to propose to Michel in producing a new silhouette animation project, which has three tales in the TV special format of 26 minutes. We could finance it with Canal+ and Channel 4 with a great British producer, Clare Kitson. We made a beautiful TV special named Les Contes de la Nuit (English title: Tales of the Night).”

Soon after, Brunner discovered that Michel Ocelot’s approach is too artistic for a TV series. At that time, the kind of animation French TV channels want are series of action and adventure, inspired by Japanese Manga. So, Brunner decided to change his path and told Michel Ocelot, “I think for TV, it’s over. We would never succeed in financing your project with the funding from TV companies. Perhaps we could try to make a movie, for cinema.”

The birth of Kirikou et la Sorcière

This became a turning point for Brunner. After suggesting the idea to Ocelot of changing the format to films, Brunner received a script from him, which becomes Kirikou et la Sorcière (English title: Kirikou and the Sorceress), one of the historical masterpieces of French animation.

Brunner still remembers the feeling that he had after receiving the script and illustrations: “It was amazing, incredible, beautiful, and with very expressive design. I immediately felt that I had in hand a great film project. Michel and I decided to try to find the funding to make this film. At that time, animation for cinema in France was complex and non-existing.”

According to Brunner, it has been a great difficulty with this project to find distributors or investors in France, due to its strong artistic challenge at that time. One of them is in the opening scene: It is the nativity of a little African baby, who is the main character of the film, that Ocelot wanted to keep. Another one is having the women and children in the film be completely nude, which could be perceived as provocative. Brunner said that Michel told him, “I want the film like that. I don’t want to dress the women and children because my film takes place in Africa in the 19th century, an old time.” As a producer, Brunner tries to create the film while keeping in line with Ocelot’s artistic direction.

Brunner recalls, “Canal+ was a channel that wanted a film to highlight its differences compared to the other channels. It was at the very beginning of Canal+ and they came on board for this project. We also got the funding of the selective commission subsidies named ‘Avance sur recettes’ from the French national film centre*1.

*1 the official name is “The National Center for Cinematography and Moving Image (CNC)”.

Brunner also found a Belgium and a Luxembourg producer, and the budget for the film project reached €3 million. With that, they all decided to start making the film. However, during production, they found themselves going over budget. It is their first animated film, so they were close to failing the project. However, Brunner found a good distributor who places a minimum guarantee for international rights and helped them finance for the rest of the project. Brunner says, “Canal+ had put more funding than at the beginning of the project, so we could have enough money to finish the film.”

The unexpected success of the film

When the film Kirikou et la Sorcière was completed, Brunner had to find a French distributor to release in theatres. He met Marc Bonny from Gébéka Films, and Marc took the risk of investing in this challenging film project by deciding to distribute, advertise and market the film. The number of opening theatres in France was less than 60, which was a very small release according to Brunner.

In spite of its small release, the public’s response to the film was much better than expected, and ended with more than 1.5 million ticket sales in France. Brunner remembers: “The people were very enthusiastic and the theatres became full. Then other cinema owners wanted to have the film in their theatres. It was a surprising success.”

Encounter with Sylvain Chomet

During the time when Brunner was producing Kirikou et la Sorcière, he met Sylvain Chomet. “He came with a crazy project of a short film titled the Old Lady and the Pigeons. The designs, the drawings, were absolutely fascinating, amazing, and the story was totally crazy. I fell in love with the project. I very suddenly had the strong desire to help Chomet make this short film.”

A problem lies ahead: the funding. Generally speaking, it is difficult to find the funding for a short film, and the project was very ambitious, budget-wise. “The budget for this short film of 23 minutes was about €700,000. In France it was about 4.5 million francs. And of course, we couldn’t fund that much money in France, so we got subsidies from the French National Film Centre to make the film, but we didn’t have enough money to produce the entire short film. I proposed to Sylvain Chomet about making something like a trailer, instead of making the film. I used the money, which was given to make the film, just to make a trailer in order to promote the film, and then find the money to make the short film. It worked, because the little trailer was very, very, very funny, beautiful, and very strong. I could find money in France with France Télévisions. I could also secure financing with Colin Rose, who was responsible for the BBC animation unit at that time and with Telefilming Canada.”

Funding from Canadian and British partners, and from France Télévisions, they succeeded in securing an abundant amount of budget for the short film. The film The Old Lady and the Pigeon came to life and ended with great success, winning the grand prize at Annecy.

Producing an Oscar-nominated title

Brunner and Chomet moved on to the production of an animated feature, because Chomet came back with an idea of a new project, The Triplets of Belleville, which gave them a new challenge. Brunner first had to convince everyone that there is a market for animated films aiming for an adult and adolescent audience, as The Triplets of Belleville is not a film for children. He succeeded in securing funding to produce the film like Kirikou et la Sorcière, with the support of the French National Film Centre and funding from Telefilm Canada. They also had Belgium funding, which made up 15% of the final budget, which was secured by a Belgian producer, who was Viviane Vanfleteren.

The film was a huge success, being selected in the Cannes Film Festival for out-of-competition official selection, and was nominated an Oscar. This contributed to huge financial success in France and America.

A new wave in French cinema

Brunner explains that this success became a milestone in changing the landscape of the French animation film market. “All of a sudden, French producers and creators of animation discovered that there was really a market for an animated feature coming from Europe, and coming from French creators.”

Not only did the creators change, but also the audience changed their perception toward animated features. Brunner believes that Kirikou et la Sorcière‘s success marked the beginning of a new era, and became the start of a new wave where the French audience discovers that animated films is not only made up of Disney, but there are lot of other kinds of animated films. Around this time after the release of Kirikou et la Sorcière, for example, 20th Century Fox’s Anastasia, and DreamWorks Pictures’ The Prince of Egypt, were released. From Japan, My Neighbor Totoro, which was one of the first animated features from Hayao Miyazaki, which came to French theatres, and Porco Rosso followed.

“What happened during these 20 years when I was still a producer in my company, Les Armateurs (that I now left), a lot of French producers and European producers began to initiate animated feature projects. La Prophétie des grenouilles (English title: Raining Cats and Frogs) by Jacques-Rémy Girerd, Zarafa, produced by Valérie Schermann and directed by Rémi Bezançon and Jean-Christophe Lie, and a lot of other films from when Kirikou et la Sorcière was released in theatres. In France, more than 100 animated features have been produced.”

French animated features continue to flourish. “I think that at the very beginning of this revolution was the little African Kirikou, who gave the signal to initiate the conquest of the French and European audience by word-of-mouth. The French animation industry produces between 3 and 6 animated features a year now”, says Brunner.

Working with passion and love

We asked Brunner how he could keep producing these wonderful titles. “I cannot say. When you are a producer, you fall in love with a project.” He continues, “I’m not an omnipotent producer. I’m not making business with cinema, I’m making a film and each film is a prototype. Each film is a risk, each film is different for us. We are more artisans, and each film is a love affair.”

He placed importance on love to the project, and had a strong desire to make the film because it is difficult to find the funding to make an animated feature, even today. Also, it is important to have hope that you will succeed; it is not impossible to make a film.

The story behind Ernest and Célestine

Brunner says that each project has its own story on how it was made. “Ernest and Célestine is another story, like the story how Kirikou et la Sorcière was made. The Triplets of Belleville had a story, and Brendan et le Secret de Kells (English title: The Secret of Kells) had a story with Tomm Moore.”

The story behind Ernest and Célestine was unfolded. Brunner used to read the book series to his little girl when he was a young father. As he read it every night before she goes to bed, he fell in love with the drawings, the universe, and the ambience of those books. At that time, he was already a producer for an animated feature, so he had the idea of adapting this book to the film.

He tried many times to get in touch with Gabrielle Vincent, who is the original author of the series. She said to him that the series will not be adapted while she is alive.

Time goes by, and while he was forgetting about it, he got a call from his friend that the adaptation rights became available by the publisher Castleman, and asked whether he is still interested in the adaptation. He immediately called the publisher and found out that the niece and the nephew of Gabrielle Vincent decided to put the rights of the book on the market after her death. He met the nephew and purchased the rights for an adaptation.

Meeting with Daniel Pennac

After obtaining the adaptation rights, it was time to find the right scriptwriter and director. For the scriptwriter, he had a book from Daniel Pennac, named L’Œil du loup (English title: Eye of the Wolf) and Cabot-Caboche in his library, and decided to try to contact this famous French novelist and best-selling author. When Brunner called him, Daniel Pennac asked why Brunner asked him to work on the script of the adaptation of Ernest and Célestine. It was revealed that Daniel Pennac knew Gabrielle Vincent very well, and they had 10 years of correspondence with letters, although they have never met. Brunner had no idea that they had this correspondence, and for him it was like a sign from the heavens.

Brunner and Pennac had a meeting, and Pennac began to work on the script. Brunner says, “We had a real convergence. We had the same desire to make a script at the same time so close to Gabrielle Vincent, but also close to the universe of Daniel Pennac.” Because the original story is not long enough for a feature film, Pennac developed a feature-length story. With that, they were able to find a French investor like Studio Canal and a co-producer in Luxembourg.

Finding the right director and building a great creative team

The next step is to find a director. Brunner phoned Annick Teninge, who is a director of La Poudrière*2, Valence, France.

*2 you can find our article about the school here.

“La Poudrière is a great school, and the only school that teaches directing animation. She told me that you must see the film La Queue de la Souris (English title: A Mouse’s Tale) from Benjamin Renner, and she sent me this little short film. I was immediately impressed by the work of Benjamin, who I did not know at that time.”

Brunner met Benjamin Renner and explained to him about the project, and showed him the Ernest and Célestine books. Some weeks later Renner came back with little sketches. They are not exactly, but very close, to the designs of Gabrielle Vincent.

Brunner recalls, “The little sketches were very, very funny, and of course, for me, it was evident that he must work on the film, but he was very young. He was just coming out of the school, so my first proposal was for him to be an art director and animation director on the film, then we agreed.”

They had to create a small trailer to sell the film, but did not have a director for the film yet. Brunner decided to ask Grégoire Sivan, who has been nominated a César Award for Best Short Film, to direct the little trailer with Benjamin. Grégoire Sivan came on board and completed the trailer.

After finishing the trailer, Grégoire Sivan came to Brunner and said, “I’m not a director for this film, you must ask Benjamin.” Brunner asked Renner and the answer was “No.”

Renner was reluctant to take the job as he felt that he did not yet have enough experience to take in charge of such a big boat. Brunner insisted, and Renner came back later with an idea of working on a film with a co-director.

Brunner had a discussion with Vincent Tavier, just after he had became a co-producer of the film. Tavier suggested Stéphane Aubier and Vincent Patar, who directed Panique au village (English title: A Town Called Panic).

Brunner met Patar and Aubier to suggest making the film with Renner. After a month of consideration with Patar and Aubier, they all agreed to get on board to support Renner. This is how the incredibly talented creative team for Ernest and Célestine came to life. Patar and Aubier, who had experience directing a popular series of stop-motion short films, worked in complement with Renner, and Renner worked as lead director.

Brunner says, “It’s what I told you at the beginning, each film is a special adventure, a specific story between the producer and the creative team or director or author. This film is the result of teamwork, which was very impressive because they were all listening to each other. Although there were some moments of conflict, the film has been done with real harmony among all these creators: Renner, Patar, Aubier, and Pennac.”

2. Interview with Benjamin Renner

Developing the right visuals while keeping the original vision

The visuals of Ernest and Célestine resemble watercolor-style paintings with a lot of texture. Renner says, “We have to find the right balance and the right mix. So, we tried to keep the spontaneity of the drawings as something that felt rough, but also not so rough that it’s shaking everywhere. We get the family of Gabrielle Vincent to sometimes check if it was looking okay.”

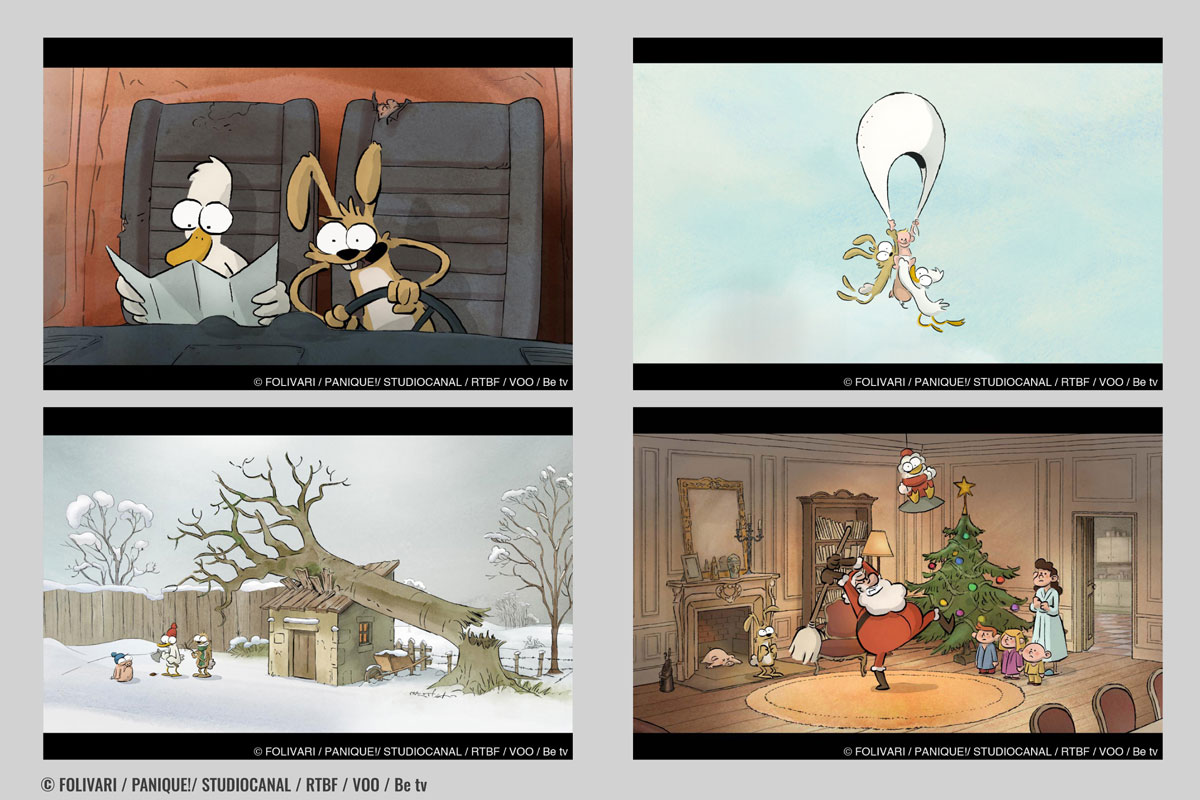

The Big Bad Fox and other tales…

After having success with Ernest and Célestine, Brunner had a chance to read a comic that Renner was drawing.

Brunner recalls his first impression when he started reading it, “It was so funny and a huge pleasure to read the book that I immediately thought that we must make something with these books for theatre or television. I proposed to Benjamin to make an adaptation of this book, but a self-adaptation, as it was a nonsense to propose to another director about adapting the book”. The project started to take shape.

The origin of the animal characters

One of the attractive points of The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales… is having lovely and enjoyable animal characters.

Renner explains that his fascination with the animal characters comes from his young age. “In France, we have a very famous author, like in 16th century, I’m not sure, but she was always telling tales about animals, like the crow, the fox, and the story of a rat and a lion, and I really loved the stories. I always loved those little stories because they told a lot of things about humans, but with animals, so I think when you use animals to tell something about humans, it always feels true because it’s animals, it’s like a tale and feel like it’s connecting with the others. And when I directed Ernest and Célestine, I already had the idea of The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales…, but it helped me a lot to make connections between Ernest and Célestine and The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales…, even if it is not obvious. I know I wouldn’t have made the same graphic novel had I not made Ernest and Célestine.”

The initial idea of the story goes back to the time when Renner was very young, like around 6 years old. One day, he visited a farm and there were eggs ready to hatch. He wanted to see the eggs hatch, but his father told him not to stay there because the little baby chickens will think Renner is the mother when they see him first. Renner thought that he’s not yet ready to be mother.

This little story stayed in his mind and kept wondering: “How is that possible? What would happen if I had to raise those chicks? Would I have to teach them to be a chicken or would they learn how to be like me?”

After Ernest and Célestine, he thought it may be the right time to finally create the story, and started drawing a graphic novel. He says that animating the story was in his mind, but he wanted to make a story quickly rather than taking five years to develop.

Ideas coming from real life

There are a lot of funny stories in The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales…. Renner describes that coming up with these ideas was a very abstract process. “I was inspired by my three nephews who are much like the chicks, in the way they act, how they are very grumpy, and everything about them, so I thought out in the book how to express what I felt with them. As I do that, I just drew sketches and I drew a lot, lot, lot, until I have an idea that makes me laugh, then I try it that way, I find out it’s not very funny, so I try another way, until I have an idea that’s funny. It’s almost like acting, improvising in theatres, except it’s in drawing. Making lots of scenes and sketches is the key.”

Feedback

“I always wait until I have a completed first draft to show people, so they can have the complete experience when they discover the story”, Renner says. By doing that, he gathered a lot of feedback for The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales…. He thinks about it, and keeps it or redraws it when necessary.

His drawing style of this work came to him naturally, as it was the style that he had for years. What was difficult for him was explaining how to animate to his team. He gives an example: “When you draw a fox for the animation, it is obvious in my head how he would look from a certain angle, but it is not for others. I have to find a way to express that to the team, so that they can draw it right.”

Animators are just like actors

The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales… is full of fun action and movement. Each animator is key in bringing the animation to this level. Renner explains that an animator is just like an actor who is good at sensitive scenes or action scenes. “It is almost like a casting actor for each sequence. You’re not going to ask Woody Allen to play in an action film. For animation, each animator is working on the same characters. You have to ask them to do the right things.”

“For example, the little chicken in The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales… is only done by one. He was really good in making that. We don’t know why.”

Music and voices matching the story

Music for The Big Bad Fox and Other Tales… is produced by a Canadian producer. Renner says, “I can’t play instruments and I don’t listen to much music, so I don’t have knowledge of music, so I completely trust him.” He composed music based on the storyboard and animation that Renner sent. He tried to propose a lot of compositions and they discussed to find the right music. For example, Renner says, “During the whole process of production, we discussed things like: ‘Here, I think it should be more intense’, or ‘I think there is too much music here. You should put more like this’. I like to let people express themselves, and I don’t want to be the kind-of composer.”

Another major part of animation is finding the right voice. Voice decides the funniness of the scene in addition to the animation. Renner says, “You have to be sure it’s going to be funny, even when you just listen with no pictures. If you’re laughing, half of the job is done.”

When Renner starts working on the drawing, the first thing he does is to think of the voice. He draws a lot of poses just to explain exactly what he wants. “For example, if on a sentence at some point in the story I’m already convinced that I want the character to look like he’s saying something like ‘yeah I’m not sure about that’, I’m drawing this pose so that the animators knows that he has to do that. I don’t want to just have animators connect the dots, I really want them to be able to express themselves, so we try to find the right animators and try to give them the exact kind of scene that they are good at making.”

They developed some guidelines, and after that, Renner explains to the chief animator, Patrick, every detail he wants to have, and Patrick tries to achieve everything possible. They discuss the capability and practicality of it and found a common ground.

3. Working for animation

When you work for animation, there are fun times, but also difficult times. Brunner and Renner say that the big fun of working for animation is the result and the creative process.

Brunner says that the challenging part is that you must have patience, as animation is a long process.

“There are always issues. We are always moving slowly. We are always impatient in seeing the outcome of the works of the artists, all the time, from the beginning to completion of the script writing, the storyboarding, the creative design, and the background design. But, actually, until we see the moving image for the first time, we need to wait a long, long time.”

For Renner, the challenging part is finding the right balance emotionally.

“When you start a project, you always have big dreams and you think it will be the best thing you will ever do. But you never know if you will be able to complete that, especially because of money. It’s like aiming high, but not too high, so you are going to make a film that doesn’t match your expectations. I’ve been very lucky so far in that sense. I think we have a really good budget and wonderful work from the whole production team to make things. A big part of it is when you make a film, you make sure that everyone is feeling okay and everything. So far, we have been really lucky about that.”

The joy of working for animation

Brunner finds that each project is special, and it is very exciting for a producer to meet new talents coming up with new ideas, projects and creativity. “We’re never doing the same thing. It’s always a new process, a new relation, and a new excitement. Each day is a new day for me. This is what I like in this job, and sometimes we have a good relationship with the creator, with the author. Sometimes it’s more difficult, but it is always exciting.”