STUDIO 4°C is a leading Japanese animation studio that continually creates animation titles that acquires a high international reputation. Eiko Tanaka, the president and the chief producer of STUDIO 4°C, established the studio after supporting the production of My Neighbor Totoro (1988) and Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), both directed by Hayao Miyazaki, as the line producer. Since then, she’s been leading the studio on-site in the front lines, producing many masterpieces such as Mind Game (2004) and Tekkonkinkreet (2006). Their latest film, Mutafukaz (2017), is nominated for the Annie Award 2019 and Children of the Sea (2019) is currently awaiting its global theatrical release.

Ms. Tanaka remarks, “STUDIO 4°C is not an animation studio, but a team of creators”. And there are many projects, including some brilliant anthology film projects, such as MEMORIES, Genius Party and Genius Party Beyond, which had set the stage for young talented creators. It cannot be overstated how much STUDIO 4°C has contributed and what she has done for the Japanese animation industry by finding and training new creators.

It is also the excellence of STUDIO 4°C, under Ms. Tanaka’s guidance, that has marked young talents for the role of director in some featured films by pushing themselves forward by their insatiable passion for making great works, and they haven’t been afraid of business risks and difficulties due to these challenges.

Lu Over the Wall and In This Corner of the World, directed by Masaaki Yuasa and Sunao Katabuchi respectively, gathered international interest after winning awards at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival 2017 and have been winning more awards globally. Ms. Tanaka is the person who noted the two talented artists early on, and gave them the initial opportunity to direct a featured film, so they could jumpstart their career as a film director, which resulted in the birth of two great films: Mr. Yuasa’s Mind Game and Mr. Katabuchi’s Princess Arete (2001).

Business offers from around the world have been coming to STUDIO 4°C, producing masterpieces one after another, and some of them paid off as high quality international co-production projects, such as The Animatrix (2003). Hence, it could be said that Ms. Tanaka is performing a crucial role in bringing together talented Japanese creators that represent the Japanese animation industry, and the global animation industry.

Animationweek had a special opportunity to meet Ms. Tanaka at the office of STUDIO 4°C in Tokyo, Japan, and hear valuable things such as the story of the production of each of their animated features, and her passion for each title and the talented artists she has worked with. We really appreciate them for this opportunity to share her precious words, giving us insights on why she is a great animation producer.

Interview with Eiko Tanaka

1. Starting a career in the Japanese animation industry

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Could you please let us know your story on how you started your career in the Japanese animation industry and your journey in establishing STUDIO 4°C?

Eiko Tanaka: I started work for an advertisement agency soon after I graduated university, and then my boss and I at the agency moved together to NIPPON ANIMATION Co., Ltd. It was the springboard for me to work for animation. I began my journey in the animation industry as an assistant producer, and the first title I worked for is The New Adventures of Maya the Honey Bee (1982), a TV series co-produced with Apollo Film, a European company based in Germany.

Soon after I started to work as a producer, I noticed that the tasks of an animation producer, who is responsible for the entirety of an animation project, including budgeting and scheduling, can’t be handled without good management of the production process, such as keeping track of its progress on-site, and I strongly felt that I should understand much more about the field of animation production. Therefore, I worked as a producer and production assistant at the same time to learn animation production comprehensively after I asked the company to do the role by myself. I was eventually promoted to a production manager, so I’m a practical animation producer who has been trained from the start.

2.The Studio Ghibli days

Eiko Tanaka: I took part in many TV animated series projects such as Alice in Wonderland (1983), Manga Aesop’s Fable (1983) and Around the World with Willy Fog (1987), whilst working for NIPPON ANIMATION. After that, I joined a Studio Ghibli featured film project. When Studio Ghibli started developing Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), they also had a roughly 15-minute short film project titled My Neighbor Totoro directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Generally, the structure of Studio Ghibli is set up to focus only on one film at a time, and they build a new team for each new film, which dissolves when the film completes. So, Studio Ghibli at the time built Mr. Takahata’s team to develop Grave of the Fireflies. However, the story of Mr. Miyazaki’s short film project was expanding, and they thought that it will become a feature film, not a short film, so they needed to build one more development team for that. Then, they called me for my help.

There are two types of producers in a film project at Studio Ghibli: One is a producer who plans a project and prepares the budget. The other type of producer builds a production team by gathering all the people needed to develop the film and controls the whole development process, from allocating all staff to managing the whole production budget and schedule in order to complete and deliver the film. I was the latter type of producer in the film project My Neighbor Totoro (1988). It is similar to a line producer in the West.

It was around the time that Mr. Miyazaki’s new animation title was decided to become a feature film and the amount of its whole budget was set when I took part in the project. However, at that time, the number of staff there could be counted on one hand, with three core members: the director, Hayao Miyazaki, the animation director, Yoshiharu Sato, and the art director, Kazuo Oga. So, there was no desk and chair in the studio for the project. It was almost empty. I remember that I had lost hair every night during the project because I was under a lot of pressure and stress managing the completion of a feature film in only one year, including having to build the development team for the project from scratch.

After the film project My Neighbor Totoro, I undertook the same job for Studio Ghibli’s next feature film Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989). A film production company named “Fuudo Sha” proposed the film project to Studio Ghibli which would’ve been directed by Sunao Katabuchi. After Hayao Miyazaki completed My Neighbor Totoro, he took a vacation and travelled abroad to recover and freshen himself up for work. He was back to the studio from that when Kiki’s Delivery Service was near the end of its pre-production stage, with the scenario and character design completed. Mr. Miyazaki said: “Oh, this is a very interesting project”. Hence, the film eventually ended up being directed by Hayao Miyazaki, and Sunao Katabuchi as the assistant director. Working for Kiki’s Delivery Service was so hard for me as a line producer, that I actually developed gastric ulcers again and again during the project.

3. Establishing STUDIO 4°C

HN: What was the story of establishing STUDIO 4°C after finishing Kiki’s Delivery Service?

Eiko Tanaka: Around the time we made My Neighbor Totoro, there were very talented freelance creators who were called Eiga-Gyokai Free*1 in the Japanese animation industry. And they were always gathered for making a film every time a new animated feature project started.

There was only one animated feature film project every one or two years in Japan at that time. If the Eiga-Gyokai Free take part in an animated TV series project after they completed a film project, they cannot go back to freelancing until the TV series project completes. So, there is a risk that they cannot take part in a new film project when it commences if they are currently working for a TV series. Therefore, there is going to be a long period of unemployment between the end of one film project and a start of another new film project.

The Eiga-Gyokai Free were turned adrift for a while after the My Neighbor Totoro project finished. So, some creators from the production team of My Neighbor Totoro made a group called “Studio NEKONOTE” within Studio Ghibli. A feature film, AKIRA (1988), directed by Katsuhiro Otomo, was in development at that time, so creators from Studio NEKONOTE helped out in that film. Then, when the film project Kiki’s Delivery Service started, the chief development staff of AKIRA joined the development team of Kiki’s Delivery Service, which consisted of the re-grouped chief development staff of My Neighbor Totoro. So fortunately, we could have really great talents for Kiki’s Delivery Service.

Actually, Hayao Miyazaki says “I can’t create any more. I retire from making films” every time he finished a film project (laughs), and he said he will retire when he completed Kiki’s Delivery Service as well. At that time, I established STUDIO 4°C to reply to the request from some of the Eiga-Gyokai Free who worked for Kiki’s Delivery Service. The founding member of STUDIO 4°C consisted of three people: Koji Morimoto (the assistant animation director of AKIRA), Yoshiharu Sato (the animation director of My Neighbor Totoro), and myself. It was more like a group of around ten creators than a general animation studio.

*1: Eiga-Gyokai: A Japanese term meaning “the film industry”.

HN: Could we hear about the history of STUDIO 4°C so far, in brief?

Eiko Tanaka: Around the time we established STUDIO 4°C, Katsuhiro Otomo was thinking, “Even though there are a lot of great young creators, there are few opportunities for them to use and show their talents. So, I would like to give them the chance.” Then an anthology film project was planned, titled MEMORIES (1995), which consists of three short films from young artists, with Mr. Otomo as the general director. At first, it was decided that Koji Morimoto would direct one of them, titled Magnetic Rose, and STUDIO 4°C would make it. But, eventually, STUDIO 4°C developed all three short films for a number of reasons. So, it was the first big project for STUDIO 4°C.

The film project, MEMORIES, was a severely difficult task to accomplish, which was on the same level of difficulty as My Neighbor Totoro and Kiki’s Delivery Service, so I was losing my health overworking many times during the project. Katsuhiro Otomo saw my hardship and said to me, “MEMORIES was a very difficult film project, so I will plan a little simpler and easier-to-manage project for you, Ms. Tanaka”, and planned the film project Steamboy (2004). However, developing the scenario of Steamboy took a long time because it was an original story, not based on anything else.

Then, we started discussing on making a new animated feature titled Spriggan (1998) with the staff of Steamboy, welcoming Hirotsugu Kawasaki as the director*2. We eventually completed the film whilst the Steamboy project was still in the planning stage (laughs).

BANDAI VISUAL CO., LTD. took over the production of Steamboy from us and SUNRISE Inc. (one of the leading animation studios in Japan, now and at that time) completed the animation. So, STUDIO 4°C animated only the initial part of the film.

The film STUDIO 4°C made after Spriggan is Princess Arete (2001), directed by Sunao Katabuchi. I started developing the film project together with Mr. Katabuchi when STUDIO 4°C was working on the two film projects, Steamboy and Spriggan simultaneously, so I went through successive hardships indeed at that time.

*2: Mr. Kawasaki was the animation director of Stink Bomb, one of the short films in MEMORIES, and he was also in the team of Steamboy then.

4. The first films as a director for Masaaki Yuasa and Sunao Katabuchi

HN: Some projects were ongoing at the same time during a short term, and all of them were featured film projects, weren’t they?

Eiko Tanaka: Yes, that’s right. The original story of the film Princess Arete was written by a teacher of a primary school in the UK who advocated feminism. I, as a woman, started the project to make an animation for women only by women at first. But after that, I faced the question, “Would embodying the true meaning of feminism in this project entail ostracizing men from the team?” While thinking through this question, Sunao Katabuchi, who is male, took part in the project, and I chose him to be the director, overcoming my own question. I discussed with him over and over, and then we decided to propose a new vision of the princess different from Disney princesses such as in Cinderella (1950) and Sleeping Beauty (1959). In these films, only their beauty is drawn as their status. But it would be good to have an animation of a princess story that doesn’t focus on the beauty of the princess. We should have a vision of a vigorous princess who carves her own path with her own will, like Princess Arete. So, we suggested this idea of a princess from the viewpoints of women through this film.

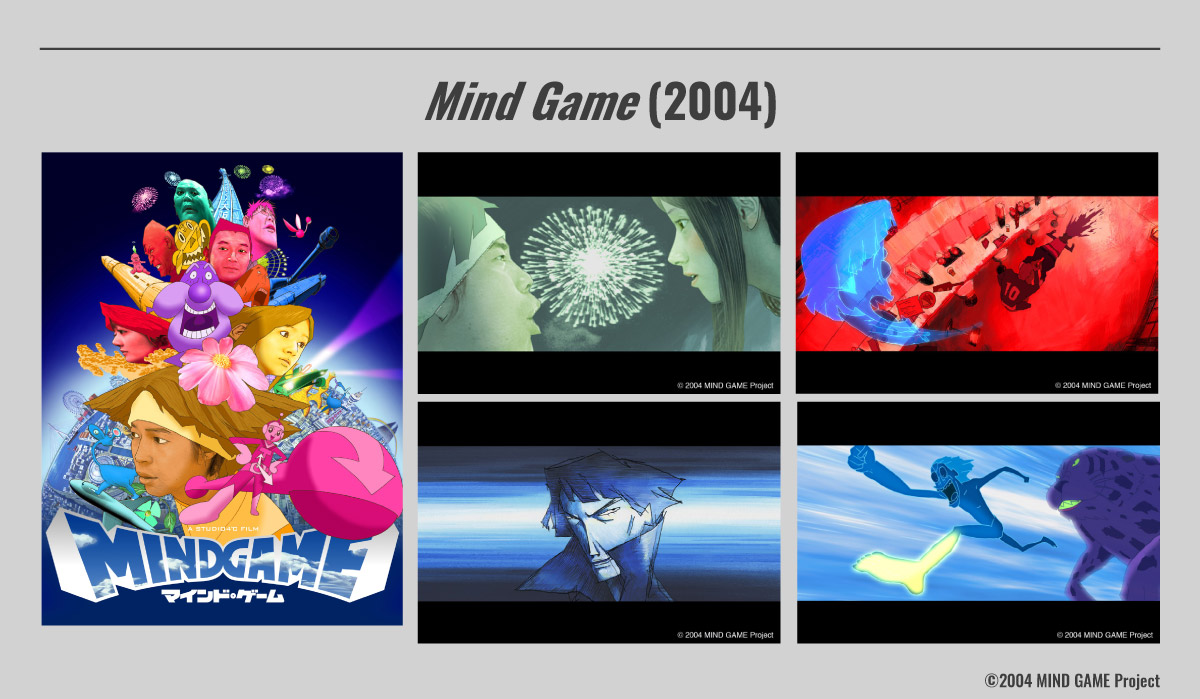

HN: STUDIO 4°C developed Mind Game (2004) after Princess Arete. How did the film project take place?

Eiko Tanaka: I came across the original Manga and loved it, and I thought it was very interesting and attractive! So, I tried to meet the author Robin Nishi personally. However, it was a really tough journey to get his contact address and meet him in person, because the magazine titled COMIC ARE! (MAGAZINE HOUSE, Ltd.), which the Manga was serialized in, was no longer being published at that time.

After I met Mr. Nishi and got the permission from him to make a film based on the story somehow, I thought: “Who will I ask to direct the film?”

I was firm with my decision: There is no one except Masaaki Yuasa for the director of this film, and I asked him: “Please feel free to make this film as what you want it to be.”

Eiko Tanaka: Mr. Katabuchi was a director of an animated feature for the first time when we made Princess Arete, and Mind Game is the first featured film for Mr. Yuasa as a director. It is a coincidence that STUDIO 4°C was the studio for both Mr. Katabuchi and Mr. Yuasa’s first featured films as directors. It was really difficult planning these two films and gathering the budget of them, because I selected young talents who haven’t had experience to direct a feature film. So, when we were able to complete the two films, through overcoming all the difficulties, I had a profound feeling: “Finally, we can give this film to the public!”

I am happy that Mr. Katabuchi and Mr. Yuasa have become big names as animation directors, which led to the two films we developed could have opportunities to be highly praised and acclaimed anew as their first featured films.

HN: Did you have any criteria in finding and determining people such as Mr. Katabuchi and Mr. Yuasa to promote to directors of featured films, at that time?

Eiko Tanaka: That kind of young talent tends to glitter in the Japanese animation industry. That is the case with Mr. Katabuchi and Mr. Yuasa. And young talent is becoming a topic of conversation during the people in the industry like, “That part in that title is Mr. Yuasa’s work. That is so good!” So, I extended my antenna to catch those kinds of comments.

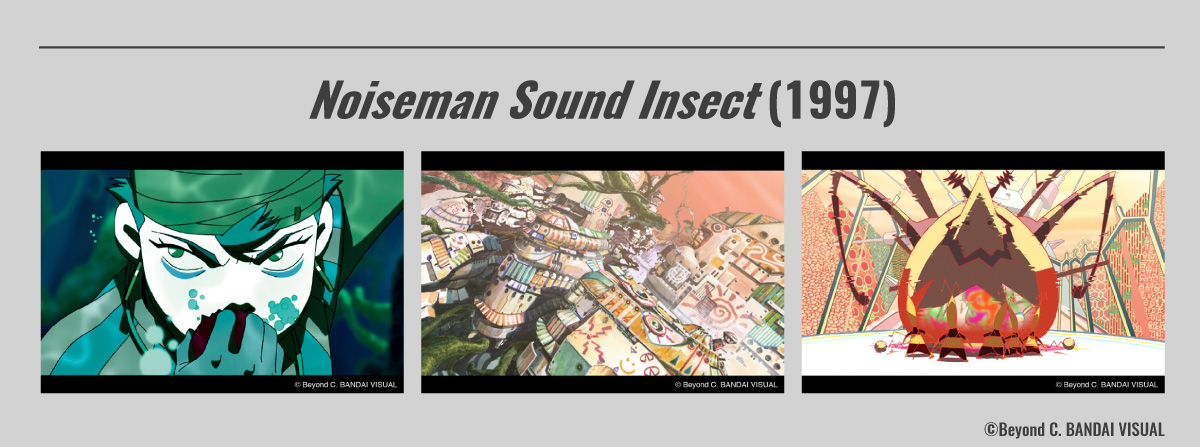

Regarding to Mr. Yuasa, he worked with STUDIO 4°C for Noiseman Sound Insect (1997), a short film directed by Koji Morimoto before the Mind Game project. Among the main characters of the short film, we asked Mr. Yuasa to direct the character Noiseman, and the other boys were directed by Mr. Morimoto. We tried a unique development approach: Mr. Yuasa drew the storyboards of all the scenes in the film which Noiseman appears, and Mr. Morimoto drew the storyboards of all other characters in the film. It was just around the time computer-generated visuals were introduced in the Japanese animation industry, and we were also trying to do many new challenges with the new development team of the short. Through those challenges, I could learn more about him, such as: “Oh, Mr. Yuasa has this great talent and comes up with such interesting or attractive or fun things!” Those things about him lead me to think of asking him to direct his first animated feature.

Eiko Tanaka: STUDIO 4°C wants to continually bring up potential young talents, one after the other, and hope that they graduate this studio as mature directors in the end. So, we have been trying to make excellent young creators gain experience by, for example, asking them to direct the CGI, and after that, make them draw storyboards of about 20 minutes for a TV series, then we prepare an opportunity for them to take on the challenge of staging for a feature film as an assistant director. Animation could be made only through teamwork, so it is important to learn how to develop a team and work together with the team for making the animation they want, in order to set up their careers. It is not what we intended to do from the beginning, but I noticed that STUDIO 4°C has made many animated shorts, and young creators could experience the whole development process of animation, including the use of sound, by directing shorts. I think that making short films helps us for training new talents.

5. The keys in making international co-production projects successful

HN: Could I hear the story of STUDIO 4°C after the completion of the Mind Game project?

Eiko Tanaka: The story goes back to one year before Mind Game. We released The Animatrix (2003). Thanks to the fame of Katsuhiro Otomo’s AKIRA throughout the world, the film MEMORIES, which we developed, also got attention from people all over the world. The producer of The Matrix (1999), Joel Silver, and the directors, Lana Wachowski and Lilly Wachowski, watched MEMORIES and thought, “We want to know the company that made such great images of the film!” Then, they visited Japan to tour STUDIO 4°C and that lead to the conversation to make The Animatrix together.

Fortunately, STUDIO 4°C has been able to work together with many talented creators to develop all the titles the studio has ever created. So, we have aimed to prepare the best environment we can to enable them to fulfill their greatest potential, and it ends up developing into good animation. After we completed a title, it could catch many people’s attention and that connects to the opportunity of our new project. Our work markets itself, which happens over and over, and it has made STUDIO 4°C what we are today.

Specifically, after The Animatrix sets off its journey to the global audience, we could receive various business offers from people around the world who watched it. Thanks to those offers, we could make an anthology film, Batman Gotham Knight (2008), and a DTV titled Green Lantern: Emerald Knights (2011), and ThunderCats (2011), a TV series, together with an American company Warner Bros. Animation. We also had good outcomes from them, such as an animated feature, First Squad The Moment Of Truth (2009), which we developed with Molot Entertainment from Russia, and an anthology film titled Halo Legends (2010), which is based on Microsoft’s very famous video game franchise.

We sent a director or an animation director to all those projects, and we did our best to develop high-quality animation that exhibits our unique visual style. The number of people outside of Japan who are looking forward to watching our new titles is now not so few, so when I go abroad and hear their kind and warm voices for our works, that supports STUDIO 4°C and me a lot.

HN: Are there any difference in business conversations you have as a producer between a Japanese domestic project and an international co-production project?

Eiko Tanaka: Regarding to First Squad The Moment Of Truth, an international co-production project with Russia, I produced it with two Russian producers, Misha Shprits and Aljosha Klimov, and their bargaining ability was surprising.

For example, I carefully explained all of my idea, point-by-point, for about three hours, and they reply: “We understand what you said”. But then they continue on to: “However we think…”, and share their opinions for nearly three hours. After that, I reply to their opinions for almost three hours. The negotiation I did with them consisted of repeating this kind of conversation over and over. So, thoroughly negotiating with them seems like discussing with them during a long and cold winter in Russia. They said “Ms. Tanaka, you are insistent”, but for me, I thought, “Russian is more persistent than me!” (laughs)

I think the most important thing for business negotiations is the same as everywhere else in the world, generally. It is that a producer falls in love with the project, and passionately conveys to the potential business partner things such as how fantastic the story is, what about the title that is so interesting and attractive, and how great the creators will develop it.

HN: The number of co-production animation projects among different countries and cultures is high nowadays, so your successful experiences can be very useful references for those kinds of international projects.

Eiko Tanaka: When you make animation via international co-production, you would face a problem of you and your co-production partner not understanding each other during the beginning of the project, which arises from cultural differences. If you develop the animation without understanding those things, the story could not possibly have good structure, and it would become an animation where the audience can’t make out what the animation conveys.

For instance, if we run an international co-production animation project with an American company, and the American team makes a request for us, such as: “This should be a funny scene, but the animation as it stands now cannot make the audience laugh, because the timing is off. So, please correct it”. It would be impossible for us to correct the animation accurately if a certain timing for a scene is not funny for the Japanese, whilst Americans roar with laughter at it, and Japanese creators can’t understand why. If the Japanese team replies, “We can’t understand the reason why that timing is funny to you, but we will fix this scene according to your instructions to comply with your request”, it would mean that the creators will draw something they don’t know and understand. It won’t be a good product.

If creators on the Japanese side can understand sufficiently about the reason why that timing is funny for an American audience, they could propose their own idea for a revision, by utilizing the Japanese’s perspective on American humor. For example, a Japanese creator could reply: “I see. That point is funny for Americans. Then, I will modify the scene like this”. Hence, when STUDIO 4°C faces a situation where we can’t comprehend the American co-production partner’s intentions due to cultural differences, we only start drawing after we understand each other over discussing it completely.

If an American team demands the Japanese team to make the scene the same as their instructions without any attempt of discussion, the Japanese team would think: “Then why would you want to co-produce with Japanese creators at this Japanese animation studio?”

So, when STUDIO 4°C does an international co-production, we state clearly in our first contract that we draw only what our Japanese creators can understand before starting the project, and we use the Japanese to develop the animation. We prepare everything in Japanese, which Japanese creators would use as the reference in drawing the animation, such as the scenario and storyboard.

6. Tekkonkinkreet

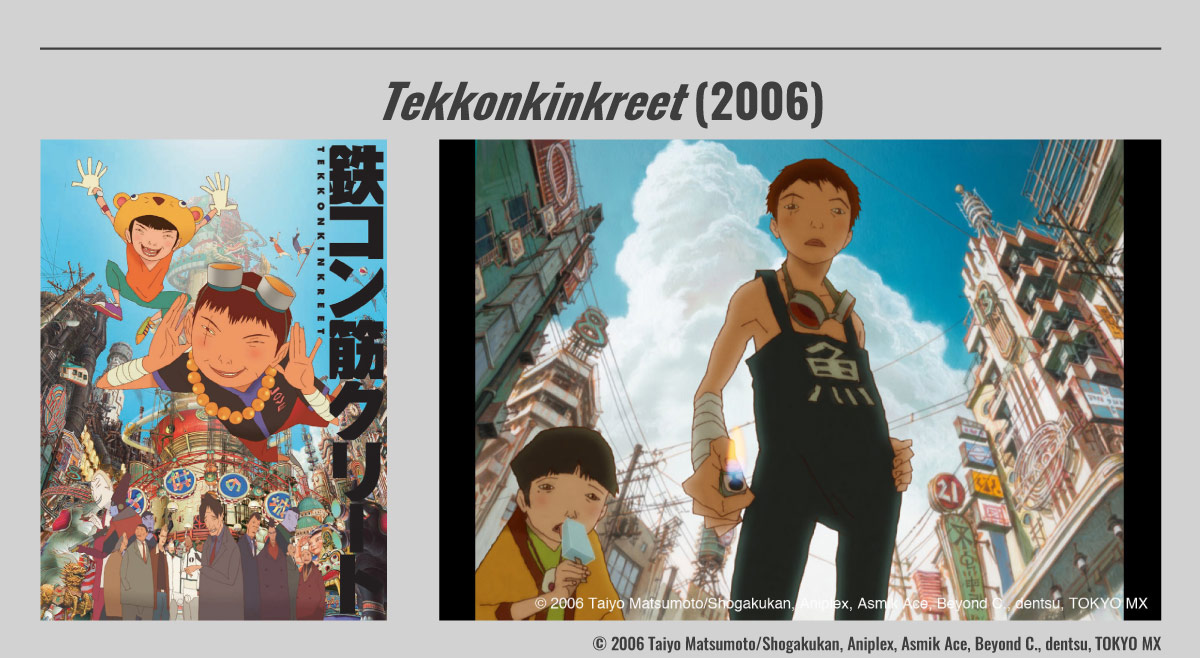

Eiko Tanaka: Let’s return to the story of our project after Mind Game, Tekkonkinkreet (2006). Just around the time we were starting the production of MEMORIES, I read the first episode of the original Manga series of Tekkonkinkreet written and drawn by Taiyo Matsumoto on a weekly Manga magazine, Big Comic Spirits (Shogakukan Inc.), and intuition had told me: “If this Manga story will be animated, the animation studio that will develop it should be us, STUDIO 4°C”.

Eiko Tanaka: When STUDIO 4°C was about to commit moving the film project Tekkonkinkreet forward, Michael Arias, one of the producers of The Animatrix, showed a strong passion in making an animated feature based on the Manga, so I asked him: “Would you like to direct this film?”

At that time, he had no experience directing animation, but I decided to take the challenge in making a development team with Michael as the director. We focused on gathering the type of creators who can show their ability well by teaming up with Michael, and we ended up developing a really good creative team for the film. Everyone did great work, including Hiroaki Ando, the co-director, Shojiro Nishimi, the supervising animation director and the character designer, and Shinji Kimura, the background art director. When Michael hits a wall and says, “I can’t understand this well”, everyone supports him like say “Ok, ok, don’t worry. We will be able to manage that”. With that, we completed the film.

7. The difficulty of gathering budget

HN: I would like to hear a story on the business side. It costs a lot to make animation. If possible, could you please let us know how STUDIO 4°C gathers the budget for each animation project?

Eiko Tanaka: I gather the budget by convincing potential business partners one-by-one, steadily, and every time it is a very hard job for me. STUDIO 4°C is a creator-driven group, which is specialized in preparing opportunities for the creators to show their ability, and making only animation which would make all the creators think, “Yes, this is a worthy and meaningful thing to animate and put it into the world”.

As a result, we tend to make an animation of our original story, or an animation based on an unknown masterpiece, not a famous and popular title. It is very difficult to gather investors for such a project because it is not an animation directed by a big name and follows the market trend. STUDIO 4°C is not a studio which develops TV series on a regular basis, so we are not rich in budget for animation production. Regarding to the procurement of funds for each title’s production, we always walk on a tightrope and just barely manage to succeed.

For example, we needed more than three years to complete a short pilot film and image boards of the Mind Game after we started the film project by gathering money steadily and developing the visuals, little by little. Then, I went back to business gathering the budget for the film with those visuals. I hand-picked people who fell in love the work through years of tireless work.

There is a scene in the original Manga of Tekkonkinkreet where an elderly person is being hit by a character with a metallic pipe. When I was looking for investors, some of people who know the original Manga said, “We can’t invest in a film based on a Manga which has a scene like that”. At that time, I explained to them carefully about the message we wanted to deliver to the audience through the film to avoid them judging from only that one scene.

8. Genius Party and Genius Party Beyond, filled with the creators’ originality

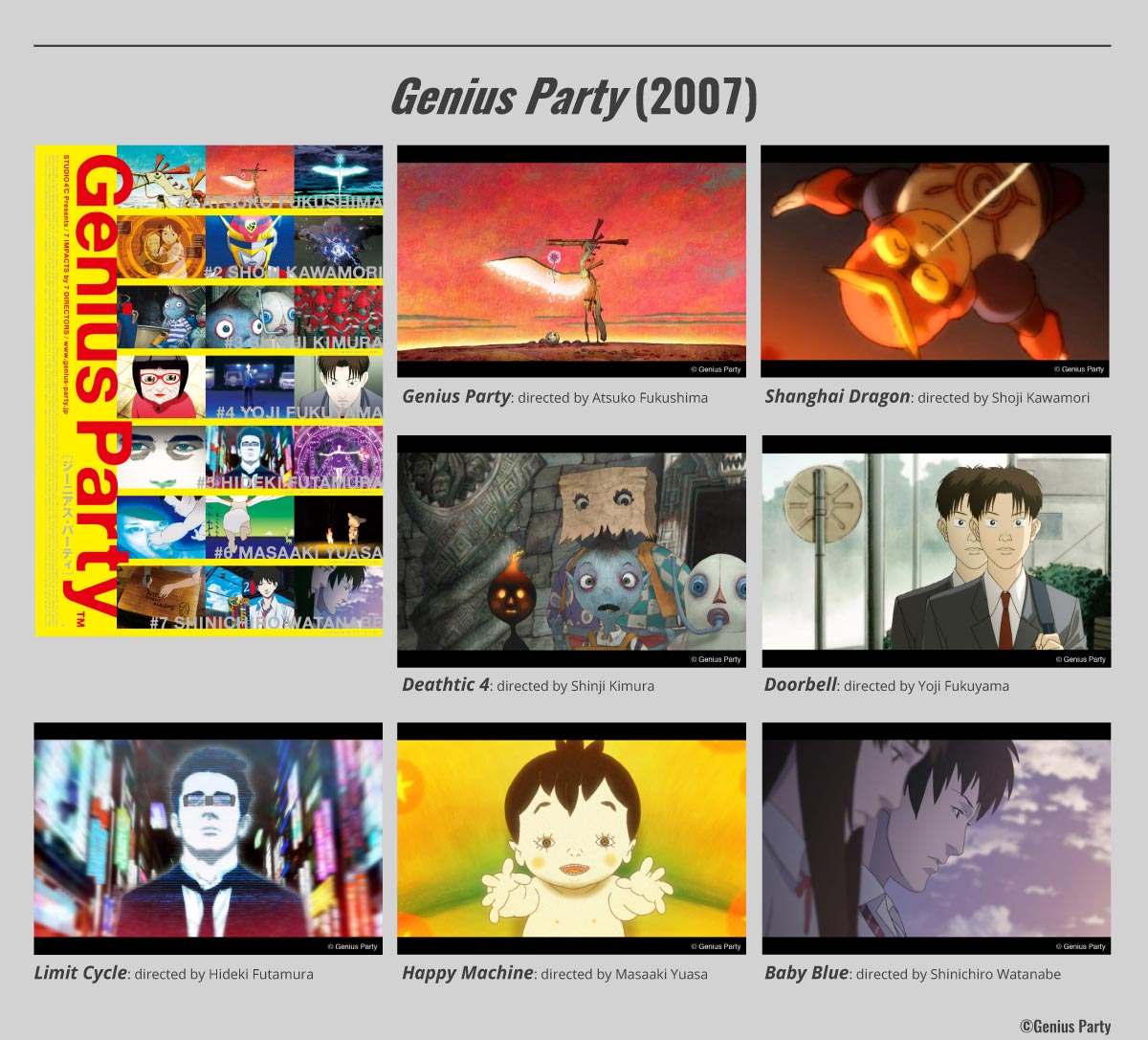

Eiko Tanaka: After Tekkonkinkreet, Genius Party (2007) and Genius Party Beyond (2008) were released.

I think it is very hard and difficult for creators to show their unique universe in animation, so if they can do that, it would give them a high reputation, like Hayao Miyazaki, who is highly appreciated globally with the originality of his works. However, it is quite rare for creators to get a chance to show their originality in animation. I have hoped that talented creators can make what they truly want to create by showing their originality as artists. That was why we planned two anthology film projects, Genius Party and Genius Party Beyond. I suggested to a variety of talented creators of taking part in those projects, and we had them direct their original short films.

Personally, I thought it was important to spotlight directors in the project, so we especially asked a professional photographer to shoot proper photos of them for the booklet of the two films, which were sold at theaters. We do not do that kind of thing normally. Among all the directors of the two anthology films, only the photo of Kazuto Nakazawa, who became famous with the animation part of Kill Bill, is not there because he was too embarrassed to show his photo (laughs).

HN: After Genius Party and Genius Party Beyond, STUDIO 4°C developed First Squad The Moment Of Truth, which you mentioned a little bit before, right?

Eiko Tanaka: Yes, and the trilogy titled Berserk Golden Age Arc (2012 – 2013). We intended to express a deep and heavy theme in the original Manga series, so they became ponderous films in the end. The sequel project of the trilogy films was delegated to another studio. It became an appealing entertainment hero story TV series.

When STUDIO 4°C was developing the trilogy, we were also making a 26-episode TV series titled ThunderCats, which aired in the USA, simultaneously. It was an international co-production with America, and each scenario of the TV series we received from the American team are sometimes shorter or longer than the actual total time of the episode. In that case, we needed to edit the scenario to fit the actual time for the program by discussing it with the American team. So, it was a really busy time for STUDIO 4°C. On the other hand, we could hear everywhere that Samuel Register, the president as well as one of the producers of Warner Bros. Animation, appreciated our work for the series. I think that’s how business connects to the future.

Eiko Tanaka: Then we made Harmony (2015), one of the three animated film projects that are all based on novels written by Project Itoh. Michael Arias and Takashi Nakamura co-directed the film.

Here’s an inside story of the project: Little before we received the offer of the film project from Fuji Television Network, Inc., by chance Yusuke Hirota, who works for STUDIO 4°C, suggested a project plan to animate Project Itoh’s Harmony, the same novel, at our internal planning meeting. Because of that, we asked him to be an assistant director for the first time in his career when STUDIO 4°C decided to make the film.

9. The pioneering introduction of Computer Graphics

HN: The characters in Berserk Golden Age Arc and Harmony were created with toon-shaded 3D CGI. Could you please let us know the history of introducing computer graphics into the animation production at STUDIO 4°C, in brief?

Eiko Tanaka: At first, we rendered a rose flower in Magnetic Rose*3 as 3DCGI by using Apple’s Macintosh Quadra, which we now call “the ancestor”. The software we used was Strata Studio Pro.

We could have the ability move the camera freely without using a physical camera stand by utilizing computer graphic technology from the production of Noiseman Sound Insect (1997). In addition, we have used toon-shaded 3DCGI rendered by a software named 3ds Max to animate tiny or complicated things such as mobs*4.

Berserk Golden Age Arc is the first film where STUDIO 4°C drew the main characters using 3DCGI. 3DCGI was the only way for us to draw and animate all the details of a lot of soldiers with complicated armor in the film, with precision. We didn’t have enough 3D animators in the production team in the beginning of the film project, so we started from bringing up 3D animators by internal training. We introduced a software named Maya from Berserk Golden Age Arc. We are still using 3ds Max, but we are gradually shifting to 2D-like animation using Maya.

*3: A short film directed by Koji Morimoto, which is one of the short films in MEMORIES (1995).

*4: Mob: A specific word in Japanese animation industry, meaning background or extra characters in animation.

HN: How do you think will STUDIO 4°C use both traditional hand-drawn 2D animation and toon-shaded 3DCGI?

Eiko Tanaka: 3DCGI is one of the ways of expressing characters in animation, so we would like to use it as one of the tools. Hand-drawn 2D animation and 3DCGI are both still character animation.

There is a unique method to make 2D-like animation by using 3DCGI in Japan. STUDIO 4°C is striving to create a sharp and comfortable 3D animation style, which is different from the way of expressing movement in foreign animation, by expanding the unique method that Japan has.

On the other hand, I feel that 3DCGI has a new power of visual expression, which traditional 2D animation doesn’t have. So, I think we have to make use of them for developing new ways of visual expressions as we use 3DCGI.

What we are pursuing is the visual quality of completed animation, so there is no problem whether we make it by traditional 2D animation production or by using 3DCGI production, as long as we obtain a satisfactory final moving image. I’m personally anticipating that 3DCGI will further contribute to our animation production in the future because 3DCGI technology and its creators are progressing significantly and quickly.

HN: Disney has a story on when they developed Tangled (2010), 3DCGI creators learned the expressive properties of traditional 2D animation from Glen Keane, and they took a long time inventing a technology and method to reproduce those methods by 3DCGI. As same as Disney at that time, there are many really talented 2D animators in STUDIO 4°C, right?

Eiko Tanaka: 3DCGI in STUDIO 4°C is developing 3DCGI production together with 2D animators as well. We started from experienced 2D animators teaching 3DCGI animators about keyframe animation, which is the mainstream method in Japan at the moment, by using rough keyframes and animatics they made. Then, the 3DCGI animators grew rapidly and were able to express Japanese limited animation-style movement by themselves after a while. Thus, we built the know-how of 3DCGI production through Berserk Golden Age Arc and made good use of them when we made Harmony.

10. The message of each title

HN: How does STUDIO 4°C decide the animation titles to develop, and what criteria does the studio have for the selection of titles?

Eiko Tanaka: In terms of finding stories to animate, either I find it myself by keeping open to new information, or I’m told good stories from staff at internal planning meetings. Thinking back, it seems like I have picked up stories with characters living with a positive mindset.

We only start each project if STUDIO 4°C can find a theme with a strong message in the story, that can be conveyed clearly through animation, and only then do we start the project officially. So, sometimes we give up a project if we cannot find any important message in the story at the beginning of the project.

If there are staff and creators who are seriously motivated to create the animation, and we think the original story has the power to provoke the desire to animate the story and bring it out, we will then commit to making a skilled team for the project, and they will complete it without any resignation and compromise. That’s the STUDIO 4°C way.

HN: Regarding to the core message of each title you mentioned, is it shared among all the team members at the beginning of the project?

Eiko Tanaka: The core message of each title is generally vague at the beginning of the project. There is definitely a big important message in the story, but we will find many different messages in a story or parts of the main important message are scattered around the story. So we, the core members in the team of the project, keep discussing about those messages, as in: “That is a message, this is also a message, it is also important”, and spin them into a larger message, which will be the core of the animation. After that, we share the message among all the staff of the project by explaining that “It is this kind of story, so these things are important”, in order to raise the quality of the visual expression in every corner of the animation.

HN: I see, you have made certain the core of the story in all your projects, and that is why STUDIO 4°C’s titles have a clear story, even though they contain a lot of information.

Eiko Tanaka: There are some cases, such as uncovering a core of a story through brainstorming at every meeting after building the production team, or just the director and I think of the core of the story over and over, and make it clear. If the project is based on an original story and the story has an well-structured and good plot, which fascinates its audiences, and can’t be compromised when we animate, our direction would be based on that story.

I’ll give you a concrete example of that. In the beginning of the film project Tekkonkinkreet, Michael Arias had a vision of the film: “The Japanese Yakuza are cool, and characters like Mr. Suzuki, a Yakuza in the original Manga story, will be globally accepted.” On the other hand, I was thinking that a characteristic of the film could be the message that societies must not abandon the weak, and it should be liberal and tolerant of the weak. I also wanted to make the film enjoyable for young couples, to make many more people go to the cinemas to watch it.

There are two main characters, Shiro and Kuro, in the original story of Tekkonkinkreet, and Kuro abandoned Shiro because he became uncertain about how to take care of Shiro through his coming-of-age, because Shiro is slow-minded and became an encumbrance to him. Abandoning Shiro, a pure-at-heart person, removed Kuro’s inhibition to his violent part of him, and makes him a dangerous person and becomes mentally ill by hurting his mind. I thought that there is a message here in that part of the story: “It is not until there is a society, which is liberal in and tolerant of the weak, that humans can enrich their heart and get spiritual happiness.” So, I shared that opinion with all the staff, and got their agreement. Then I completed the proposal of the film project.

When we made Mutafukaz (2017) with Ankama Animation, a French studio, I thought that even though the original story has many intense violent scenes, it was not the theme of the story. I found a strong message in a part of the story where a character named Vinz remains best friends with the main character Angelino, despite knowing that Angelino is an alien. So, I persuaded Guillaume Renard, the author of the original comic series and the co-director of the film, to make the film as a buddy story: “Once you are friends with someone, you cannot abandon the friendship. You can survive through anything that happens, if we stay friends”. He was happy to agree with my idea, so we re-wrote the scenario as that direction, and started the production.

Regarding to a girl character named Luna in Mutafukaz, the Japanese co-director Shojiro Nishimi thought, “I want to show through Luna that a girl can be someone who can raise a boy’s motivation”, so we expressed the inside of her emotions, which showed the relationship between her and Angelino, which were not depicted in the original comics. The story and direction of the film are a bit different from the original comics.

I think that finding that kind of core message in a story is the first hard task for a producer in a project, and sharing that message with all the members of the team is crucial in making a good animation.