Traces

Traces

Directors: Sophie Tavert Macian and Hugo Frassetto

Writers: Hugo Frassetto and Sophie Tavert Macian

Producer: Arnaud Demuynck

Animation: Hugo Frassetto, Hannah Letaif, Nicolas Liguori and Clementine Robach

Music: Fabrice Faltraue

Synopsis

Thirty six thousand years ago, in the Ardèche river gorge, when an animal was painted, it was hunted. When it is again time to go Hunting and Painting, Gwel is appointed head of the group of hunters while Karou the Painter and his apprentice Lani set off to paint the walls of the great cavern. But they hadn’t counted on meeting a cave lion.

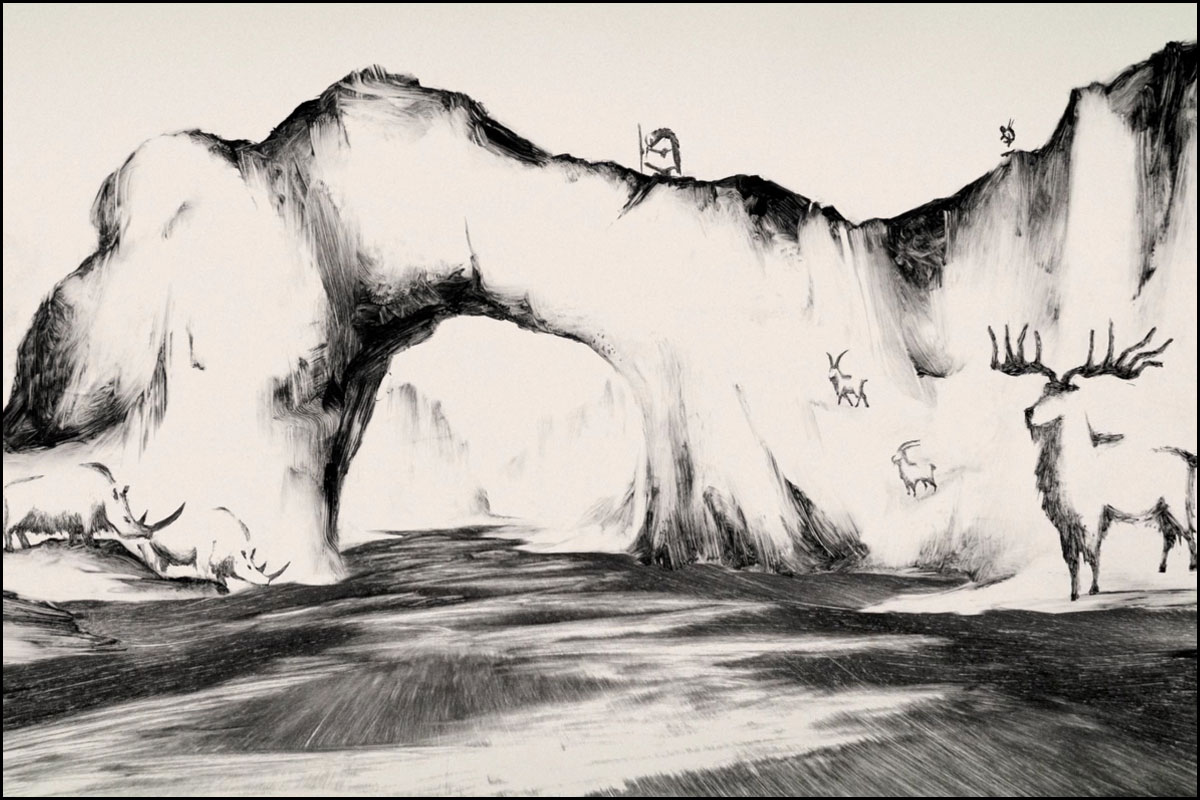

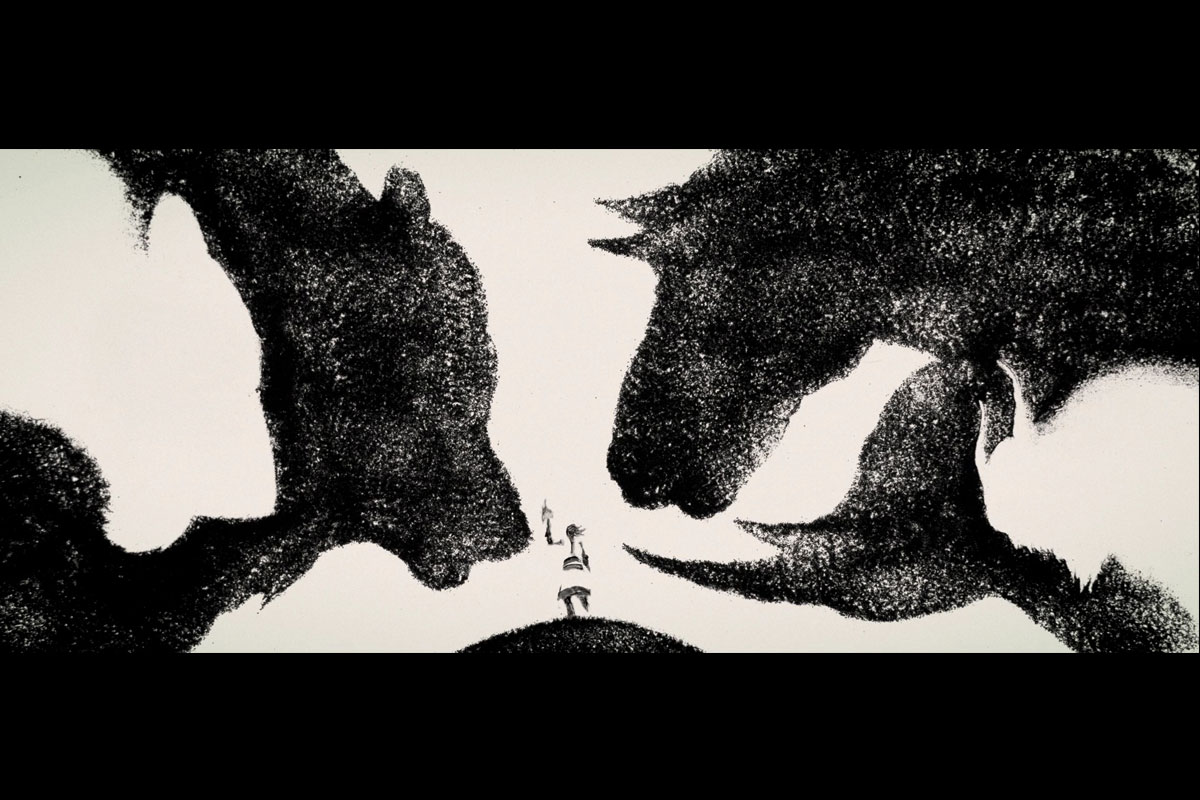

We came across the film Traces at OnlineFestival.itfs.de (ITFS 2020), which was nominated for the “International Competition” category at the festival. It is a very impressive film with impactful visuals made with a sand-animation technique.

We felt that the visuals of the film works very well to show the mysterious experience in the cave and depict the dynamic scenes with many wild animals. We think the visual storytelling, even without dialogue, guides the audience to understanding the mental conflict of the protagonist.

Animationweek had the opportunity to hear insightful words about the film from Sophie Tavert Macian, one of the directors of the film.

Interview with Sophie Tavert Macian

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): What do you want to deliver to the audience the most through this film?

Sophie Tavert Macian: The power of art and the power of picture. It has the ability to cross time and space, like a form of magic, since the dawn of time. It is a power that can be ambivalent too, terrifying and magnificent, which connects us deeply to nature, but perhaps also what has extracted us from it.

HN: Where did the initial idea of the story and the film project come from?

Sophie Tavert Macian: First of all, there’s a 36,000-year-old drawing: a fresco in the Chauvet Cave depicting a pack of lions chasing a buffalo. When I first discovered this drawing, I had the feeling that the 36,000 years that separated me from it, from its author, had completely disappeared. I was in the cave, with him or her, painting these animals by torchlight. This intense feeling, this very powerful magic of art, is what made me want to tell the story of a prehistoric artist painting magical animals in a dark cave.

Then, when I began to collaborate with Hugo, we became interested in a very broad theme: domination. It is our questioning on this theme that has built the story of this artist. Hunting and predation are survival techniques based on the domination of one species over another. The human species has partially built itself on this relationship to the world, especially during the prehistoric age, where survival was impossible without hunting. Even today, and in fact more than ever, each human being must face this question of domination. Do I have to dominate in order to survive? In order to find my place and be myself? Who must I dominate? How? Why? Whether it’s another species or another human.

In addition, just as survival is impossible without hunting, so is parietal art! The link between hunting and art, what we call the “trace” which gives the film its title, was obvious to us. The film’s symbolic world follows from this theme of domination. With its “white” component, which helps us eat, create and survive, and its “black” component which – through excess or insufficiency – wounds, destroys, and kills.

HN: Could you please let us know, in terms of story development, what you took care in the most and what was the most difficult?

Sophie Tavert Macian: In terms of the script, the writing was rather complex. The audience has to quickly understand which universe they enter, what are the rules and prohibitions, who are the characters and how they position themselves in relation to this universe. Making something meaningful, stirring up an emotion, and above all, with an unknown language.

It was a real dramaturgical challenge, since we knew from the start that we would have a big time constraint. Indeed, today in France, animation short films can hardly exceed 12-13 minutes. As they get longer, they become much too difficult to finance. So, everything was difficult!

The most important thing for us was that even if viewers didn’t understand all the issues, they were still carried away by the film. We made sure that the film was as understandable as possible, both dramaturgically and graphically. And at the same time, we gave it the maximum amount of energy.

HN: We would like to hear the story behind the visual direction. How did you design the characters and the environment of the story’s universe?

Sophie Tavert Macian: We started out of the sand first. I saw Braise, a short animated sand film directed by Hugo. I didn’t know him yet but I told myself that this technique fits well with my idea of a prehistoric artist and I contacted him. He was quickly up for the project, but he didn’t want to just exploit his favorite technique; he wanted to go further, to be even more coherent with the prehistoric context.

So we decided to take our inspiration directly from what we were going to talk about in the film: cave art. We opted for animating the painting frame by frame, because it allows us to make the “traces” visible, the finger and tool marks, as in parietal art. We chose to reduce the color palette to black, white and ocher.

For the character design, we have associated an animal to each of our characters to give them their look, by small visual touches: the bear for the Master, the lion for the Apprentice, and the wolf for the Hunter. We wanted these characters to have hybridity and fluidity, to feel how much the human being was connected to nature and animals at that time.

For the sets, I absolutely wanted to make the audience feel the austere, harsh, mineral side of this prehistoric environment. Here, we were inspired by Asian ink paintings, which play with the full and the empty, and which are somewhat very close to the characteristics of cave art.

HN: Why did you decide to use the sand animation technique to depict the story, and what part of the visual expression created by the sand animation in the film do you want the audience to enjoy particularly?

Sophie Tavert Macian: With the sand, we were looking for its mineral texture, but we also gave it a symbolic meaning in the film. Sand is the world of the cave, of the “trace”, a powerful dimension impacting reality. We wanted the film to circulate in different dimensions, and the choice of two techniques allowed us to signify it visually: the reality by painting and the supernatural by sand.

And with the sand animated by Hugo, it goes further: he is the master of sand! With this technique, which is considered difficult, he creates with astounding energy and beauty. I’m a great admirer of my co-author’s talent and I want to believe the sand part is a gift for the viewers eyes!

HN: Could you please let us know the story behind the language the characters speak and its usage in the film?

Sophie Tavert Macian: It was very important to us that the characters talk. We wanted the viewers to feel that they were in a complex, refined world of civilization. In fact, the feeling of civilization comes through art, ritualisation, learning, and also, to a great extent, through language. Indeed, we were afraid of falling into the clichés about prehistory that sometimes makes it a backwards form of humanity.

But it would have made absolutely no sense to make them speak in French! So, we decided to invent a language. I was inspired by Indo-European roots, Tagalog, Finnish, and I created a summary syntax. The challenge was to make the audience feel how rich this language could be, while at the same time giving them a few points of reference. I loved doing that, like a prehistoric dialogist!