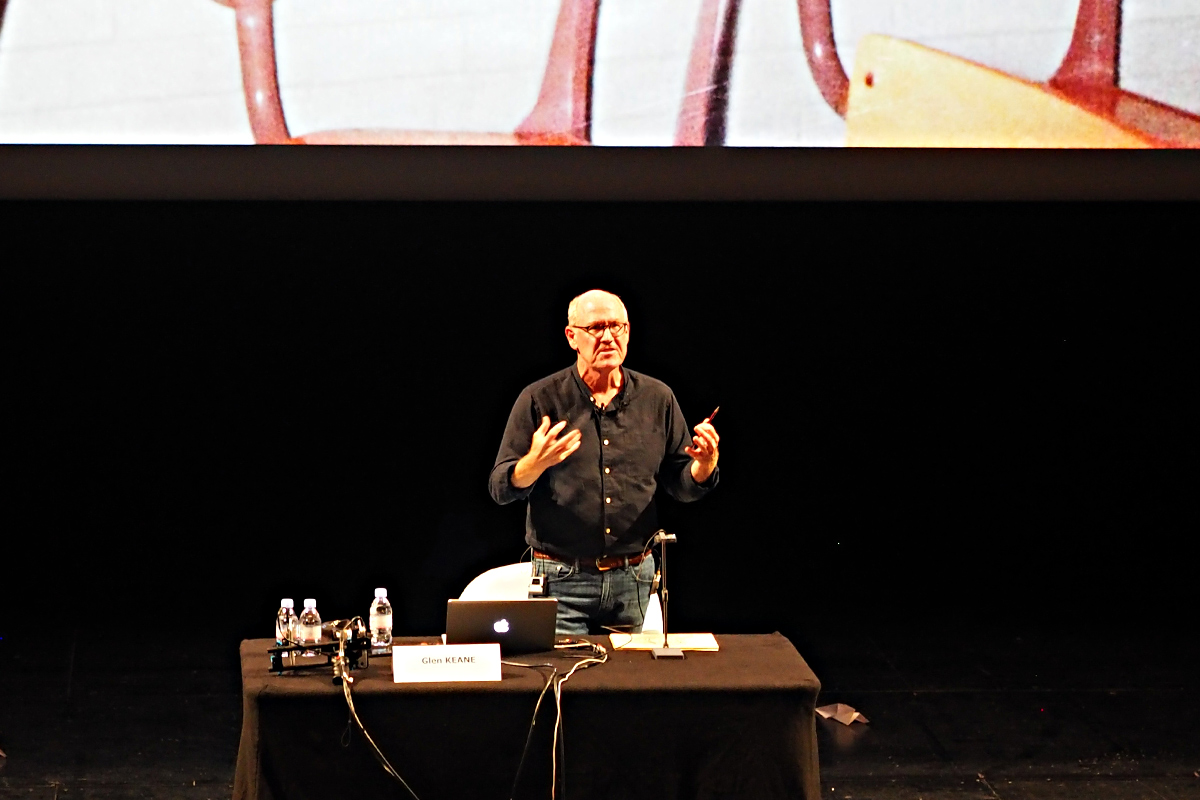

One of the highlights of Annecy International Animated Film Festival was a Keynote speech by legendary animator Glen Keane. The world renowned Disney legend, who gave life to many historical popular Disney characters, such as Ariel from The Little Mermaid (1989), Beast from Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin from Aladdin (1992), Pocahontas from Pocahontas (1995), Tarzan from Tarzan (1999), and Rapunzel from Tangled (2010), shared his precious knowledge and learnings from his career, experience and stories behind his many masterpieces.

1. Keynote Speech in Annecy

Creativity

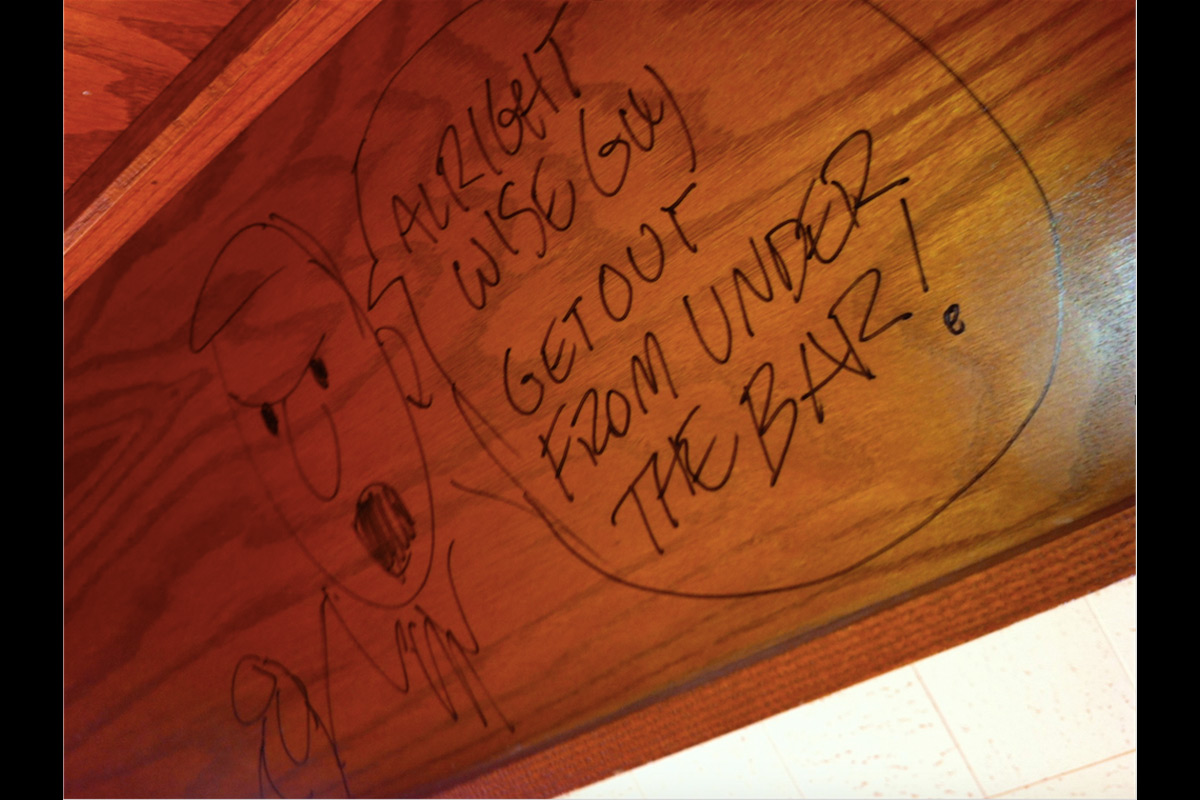

In the Keynote, Keane shares his insight and philosophy of creativity from his professional career. He defines creativity as: “doing something different from all”. His father was a huge influence to his creativity, who was a cartoonist and used to make funny drawings all around the house, such as an illustration underneath of a bar, with a comment, “get out from under the bar!”, for young Glen and his siblings to find when they were playing under the bar. Of course, his father had to be thinking like a child to be able to come up with that! Looking back at his father, Keane naturally learns to be a big kid and thinking like a child, which becomes the root of his creativity. Young Glen’s mentor in Disney was Ollie Johnston, one of the of Disney’s Nine Old Men. Glen shows us a photo of Ollie riding a mini real steam train behind the studio. “He was like a child. Animators hang on to their childhood spirit.”

What is drawing?

Keane talks what drawing is for him. He sees drawing as a way of stepping into another world, as he draws not to make a drawing, but draws to make the paper go away. He recalls one beautiful moment he had as a child where young Keane drew a nativity scene, and how he felt like his pencil is reaching as near as the hay, or as far as the stars. Drawing is a very immersive experience for him. He believes that “Drawing is the seismograph of the soul”, and “The pencil is the most direct line to the heart”. During the Keynote, Glenn gives a wonderful drawing demonstration of Beast. He remarks during the demonstration that drawing is for him like sculpting, looking beside the line, rather than at the line, focusing mainly on form. Keane shows a clip of Pablo Picasso drawing, noting that art-making is almost like a conversation with the piece.

Designing great characters

How did Keane design Beast for Beauty and the Beast (1991)? He uncovers an important tip, “Let’s play make-believe!” Believe you are experiencing the things you are drawing. Believe you are the beast. Keane had tantrums when he was a child and recalled that when animating the beast. “The characters are real in my mind, like when drawing Ariel, when she is off-screen, she is still there.” “I love characters that believe the impossible is possible.”

Openness to new mediums

Keane quotes Picasso’s words, “I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it”. After he accomplished to be one of the legendary animators in the traditional hand-drawn 2D animation world with his many great works, he challenged it willingly and worked in new digital mediums. He shows that one scene from Tarzan, which used 3D CG for background art (Deep Canvas), and it enabled dynamic compositions and camera works. Then he shares with us a story about Tangled. He worked for the full 3D CG animation film project as a 2D animation artist, and created a pencil test of Rapunzel enjoying touching, bringing up, and kicking her very long hair in 2D animation to explain his idea to the 3D animation team at Disney. At the beginning, they were hesitant in managing the movement of the hair as in the pencil test by Keane, but they finally succeeded in having the hair from Keane’s pencil test faithfully recreated in 3D digital animation.

Keane keeps challenging new digital ways of expressions and shows us some of his VR work. One of them was a video in which he drew illustrations with a VR headset (HTC Vive) and by using Google’s Tilt Brush. He explains that VR drawing is dimensional drawing. He can draw characters life-size by drawing in 3D space. He also shows us his short VR animation Duet, a story about a boy and a girl, which is being told simultaneously, and the main character of the story depends on where the viewer looks. He also had an experience with the game industry, being asked to flesh out the personality of a character. The result is a short animation of a character named Lux from the big American video game developer Riot Games’ popular title League of Legends, giving an in-depth portrait of the personality of one of the characters.

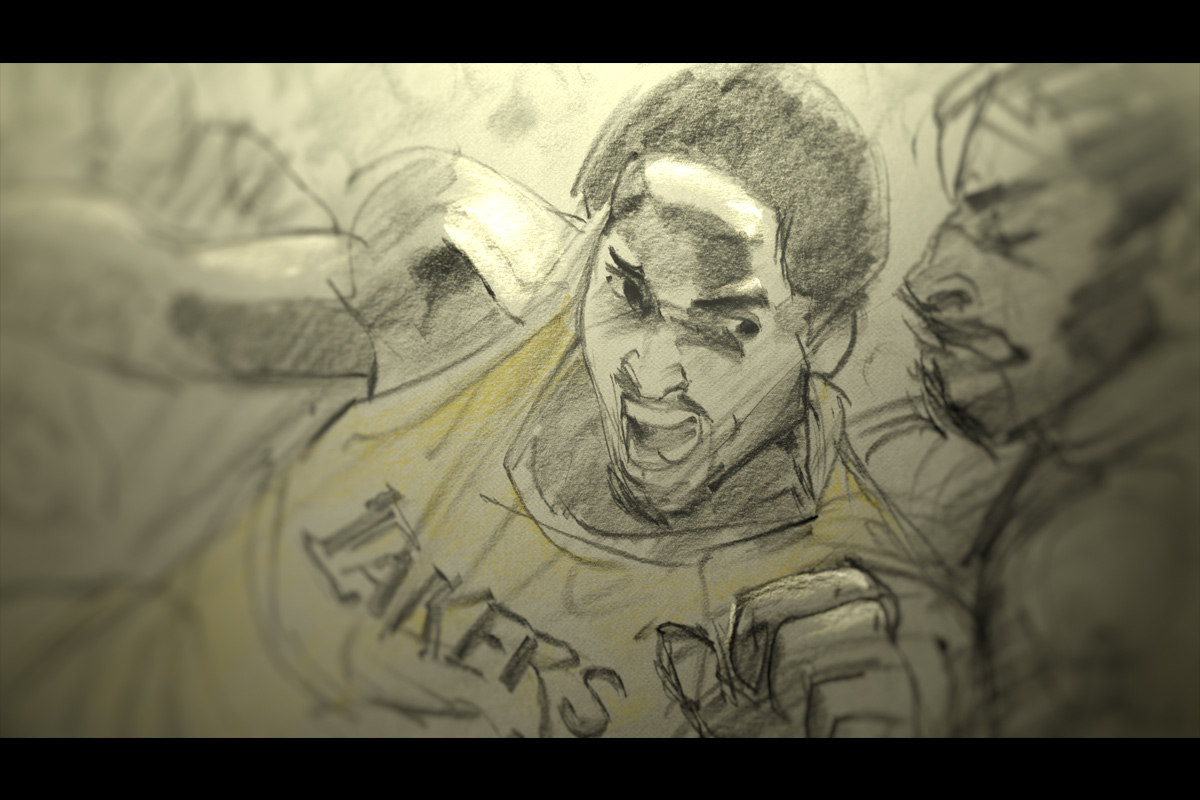

Dear Basketball

At the end of the Keynote speech, his latest short animated film Dear Basketball was played. Its story and visuals are very beautiful and leave the audience with warm feelings. We had the privilege to hear from him about his latest short animated film Dear Basketball on the next day of his Keynote Speech. We are happy to share his words with you.

2. Interview with Glen Keane

Animationweek (AW): How did the project Dear Basketball start and where did the initial idea of the project come from?

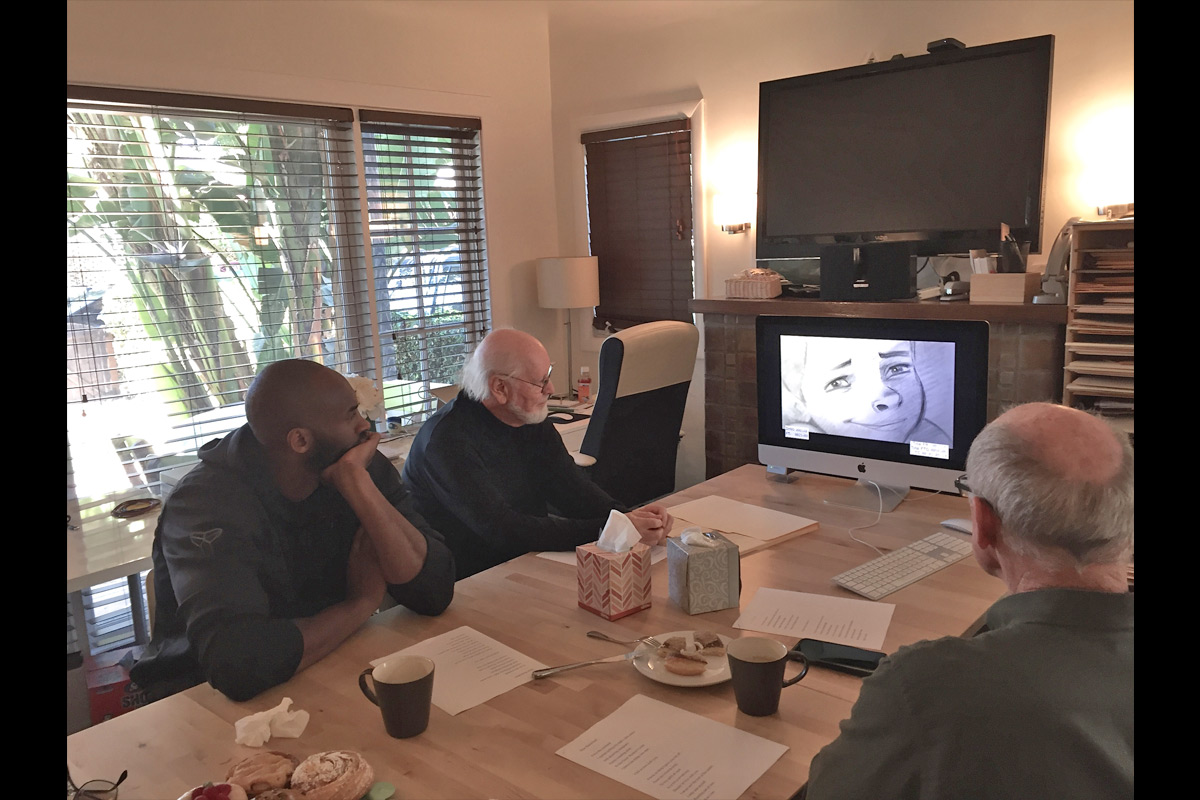

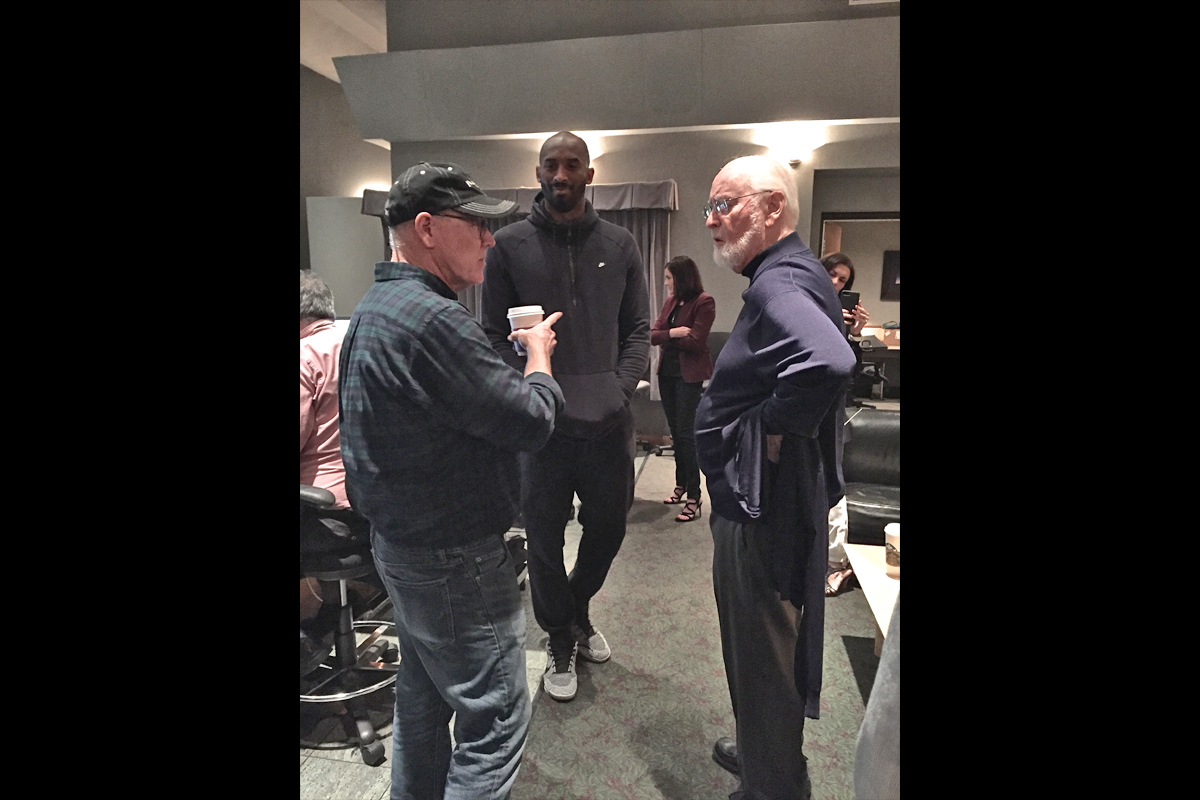

Glen Keane (GK): When Kobe was about to retire from basketball, he knew he wanted to write a letter thanking basketball from his 6-year-old boy perspective, the game for giving him his childhood dream, and he loves animation, a fan of animation, and storytelling. As he was moving out of basketball, he was thinking of his new career, which was going to be animation, storytelling, and film making, and to start a little studio. So, he was visiting all the animation companies he went to Pixar, Disney, Dreamworks, and various studios, and he had seen Duet, and so he called the Executive Producer of Duet, Karen Dufilho-Rosen at Google, and said that he would like to meet me, so he came to my studio, a very tiny studio in Hollywood. It’s just a little house we rent where our story room is in the dining room, our animation offices are bedrooms in the back. Kobe steps out of the car with his wife and two daughters, and they are coming up to our very humble house, a little studio, and I’m thinking: ‘Kobe is going to be very disappointed’.

So he comes in, and it’s the first time I’ve met Kobe. Big guy, and he’s nearly bumping his head on our ceiling, and he looks around, and all of our drawings are on the wall there and storyboards, and he just says: “This is perfect… This is perfect!” And afterwards, I said “What did you mean?’ And he said: ‘It was so real, it was like, you had drawings on the wall, and I knew that everything I wanted this film to be was hand-crafted. It has to be real. I want this film to push hand drawn animation in a new way, and it needs to have something that’s very, very intimate and personal, and that’s what your place is.’

He and I sat down and we talked for about four hours, and my wife was there, my son… It was a family. But Kobe and I really connected – not on basketball, because I told Kobe you’ve got the worst basketball player on earth animating it! But, it was on music, Beethoven, that when I animate, I animate often to Beethoven, in my mind or listening to it. These transformations were all to Beethoven’s Ninth. Kobe said, when he was playing and won one of the championships to Beethoven’s Fifth, it was playing in his head and he was orchestrating the structure of the game according to the music of Beethoven’s Fifth, so we really moved forward with music being a big part of it, knowing John Williams was going to score his film as a friend of Kobe, who had agreed to do that. He had never done a short film or animation, so that is how our relationship launched.

AW: How was the story of the film developed?

GK: Kobe wrote this letter, ‘Dear Basketball’, it was very vulnerable… He really put himself in a position where he could be easily criticized by people saying, ‘Oh, Kobe is showing off, writing a letter to basketball, that is going to be about him and asking John Williams, it’s an animation with music’, but when you really listen to what he is saying, it’s not about the praise of Kobe, it’s really about revealing the impossible dream of the child that actually is realized, and for me, and all the characters I have animated. I love the characters that believe the impossible is possible, and that it is truly that, here is this six year old with this impossible dream of becoming a Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan. That’s crazy, but he believed it and worked so hard. At one point, Kobe said, ‘I work, put in all the hours and sacrificed, more than anybody, but therefore I win’ and I said ‘yeah, but it is not just that, it is that you believed it enough to put in those hours’.

AW: What kind of things did you want to express through the animation?

GK: Also there was, what you asked in previous question, about the story. What I did first, was I wrote down the letter in every line on about three pages, and drew little thumbnail sketches of what would be happening visually with it. My son, Max, was doing his version at the same time and we would compare notes and Max immediately picked up on the folding, how do you roll his father’s tube socks into a basketball? And, I kind of overlooked that and went for bigger, more grand themes and he was zeroing in on the details and I realized how good that was to Kobe as we talked, the details were incredibly important, the posters on the wall that we drew had to be the exact posters that Kobe had on the wall when he was a kid, the positioning of the chairs, where he was positioning them on the court, Kobe drew exactly the way he put them on there and wanted to see that the way exactly Kobe would release the ball, the injuries that he made, there is a moment where you see a freeze frame and it moves slowly and there’s these places on his body, like an x-ray, where they light up, those are injuries and I picked out about six out of about 25 injuries that he had, particularly the Achilles tendon, that really ended his career.

Those details, it was my son that really showed me, that’s important, don’t skip over that. So, in all my boarding, I really zeroed in on these key moments, knowing that ultimately to me, the theme was: who you are as an adult, is the seeds that are in you as a child. As I’m talking to both of you, I see little 6-year-old versions of you, that are still there with you!

Until animating that last moment with Kobe on the court, having little 6-year-old Kobe with adult Kobe, together moving in unison as a dance… There are some moments that are a gift, and that idea that it should be, that was just an inspired creative gift. This is right, it just feels right. Sometimes you cannot take credit for something, which is given to you.

AW: I felt the lighting in the movie had a very strong role in the movie, how did the lighting effects in Dear Basketball play its role in the storytelling?

GK: That was my son, Max. He is our production designer, was for Duet as well as on everything we’ve been doing, and we will always have a direction of the lighting. We were animating a stadium in perspective, that the camera is moving, so it is not just the stadium that is still; the stadium is turning, and you were seeing crowds of thousands of people, but you can’t draw thousands of people, so you can draw the people by way of letting it go into the dark and flashes of cameras coming on in the back, people taking pictures… That’s telling you that there are people back there, clicking their iPhones and taking pictures. We would do that also with sweat on his face, picking up where the light was hitting, which was very important, and accomplished two things: it gave you a sense of dimension to his face, but also allowed me to animate the exertion, which was creating heat in his body, because there’s sweat on his face, he’s working hard, and the only way you can draw sweat is to have little droplets running down his face, but this is animation! This is crazy! And I’m thinking, I cannot believe I am drawing Kobe’s sweat going down the side of his face! And how do you do it?

I found that if I could animate with graphite, on top of the drawing, and then on my iPhone, if you click it three times, it reverses the image, and so all that black graphite goes to white and looks like glimmering sweat, and if you take your eraser and erase down the middle of a field of that white, it looks like a little rivulet of sweat is revealing the skin underneath, a little dot of sweat that is picking up the highlight. That was so, so cool, it was by far the hardest thing that I’ve ever animated in my life.

AW: How did you work with Kobe Bryant, what was it like working with him?

GK: There was one moment I had in the film where I wanted to show the love of his team and everyone coming around hugging him, I think it was where he had an eighty point game. But Kobe didn’t want that, he wanted instead to focus on his injuries, the pain. The way Kobe wrote the whole letter was this wonderful cinematic structure that it builds to this point where he’s standing there in the aggregation of the crowd, he’s at his pinnacle, but then his body can’t keep going and that’s when we show this x-ray of all of his injuries, and he’s stumbling and he just can’t do it any longer. This is a wonderful climax that drops down and builds into a bigger climax at the end, I found Kobe can be a very cinematically smart person, really aware of storytelling, the dramatics of film making, so wherever he was making comments and suggestions, they were always for heightening the dramatic tension, particularly in the end sequence, he had some wonderful suggestions that really helped.

AW: In the Keynote, you were so open to trying new forms of animation, so what do you feel is the most important thing adapting a new workflow?

GK: I wouldn’t say workflow, I would say a medium, a new medium of animation, like drawing in virtual reality; it’s a new tool. I think I’ve explained about a pencil is the ultimate simple tool, in that simplicity is the ultimate sophistication, and you become intimidated by new technology, by a medium that you don’t know understand, like up at Google, or working in virtual reality, and you think you don’t have the knowledge to do it, but you really do, because that new medium, what’s going to make it work, is going back to the foundations that you stand on, like for virtual reality it’s your child-like imagination, it’s about believing that your characters are real and if you hang on to that, you’ve got the tools to step into that world and believe in it and to actually draw in that dimension, I really had to reach into that part, not the really smart scientist, that I am not! I wish I were, the mathematician I am not and wished I were, but instead, it was me saying as a kid, ‘I want to play make believe’. I think that is really important to go back to those foundational, creative impulses you had as a kid.