Synopsis

Set at the dawn of time, when prehistoric creatures roamed the earth, Early Man tells the story of courageous caveman hero Dug (Eddie Redmayne) and his best friend Hognob as they unite his tribe against an mighty enemy Lord Nooth (Tom Hiddleston) and his Bronze Age City to save their home.

Early Man, Aardman’s latest film, is a prehistoric adventure of a small Stone-age tribe uniting and fighting against an intimidating Bronze-age city to save their home. The film was released in the United Kingdom in January, 2018.

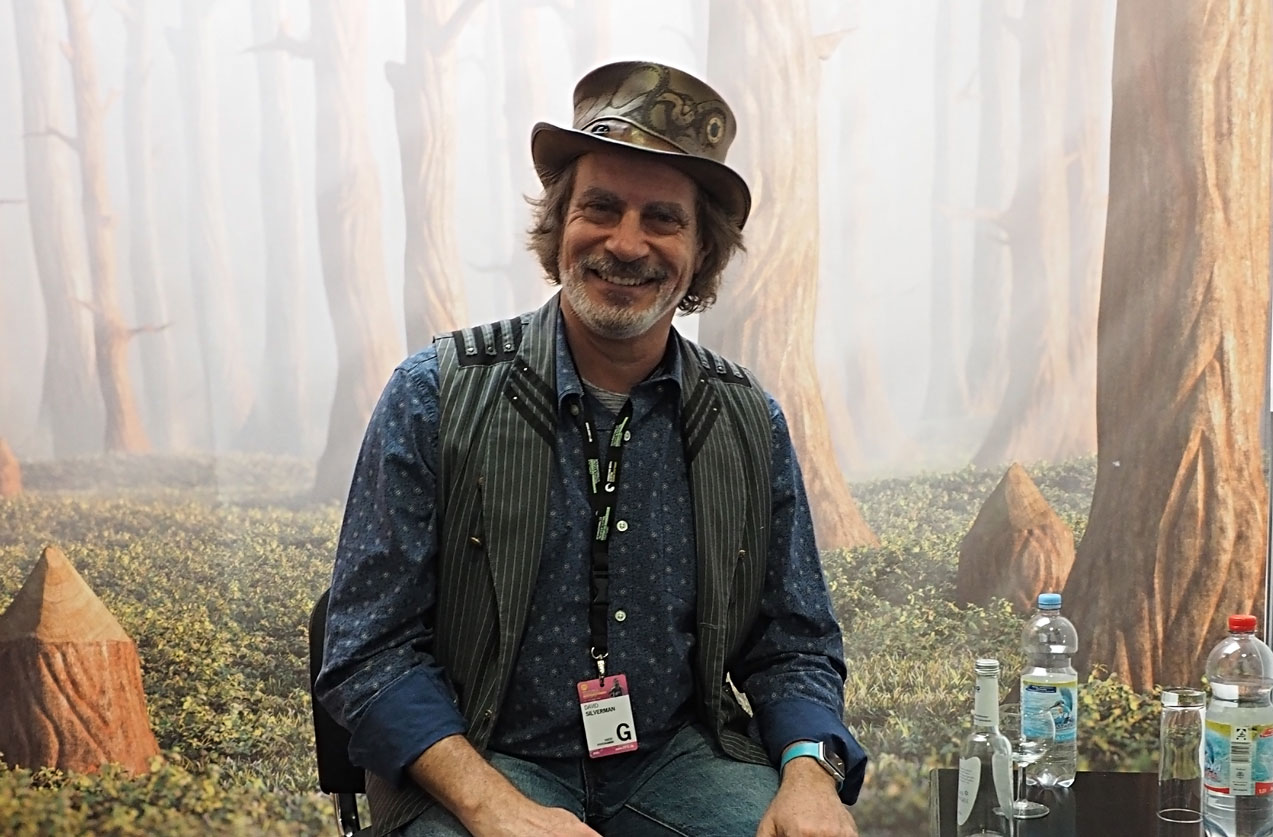

During our visit to FMX 2018 in Stuttgart, Germany, we were excited to interview one of the producers of the film, David Sproxton, who is one of the co-founders of Aardman, having produced films such as Chicken Run and Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. He is also a member of the Advisory Board of FMX 2018. We are happy to share Sproxton’s words with you on his time as a producer of Early Man.

Interview with David Sproxton

Trayton Scott: How did the Early Man film project start?

David Sproxton: Early Man has been the idea of the origin of football, which has been in Nick’s head for many years, and it goes back a long time, probably 7 or 8 years ago. He came up with this idea with cavemen… Cavemen that used to club each other to death, and that’s how they sorted out their conflicts and disputes. So, how did football come about?

We had this crazy idea of the meteor and stuff like that, which is in the prologue that you will see in the film, that encapsulates that early idea, and I think these things start in where you’re in a pub, having a drink, watching something on TV. Nick’s not a football fan at all, he doesn’t watch football much, I don’t watch football much, so it was surprising that he came up with that idea. It’s a fun idea, I think it was the contrast between the very primitive cavemen and this grunting culture that they had, and the idea that somehow along the way, somebody came up with the idea of basically sports, being used for conflict resolution, and it’s actually a better way of being more collaborative than beating each other over the head with clubs.

Trayton Scott: What do you think are the most attractive selling points of the film?

David Sproxton: Well, it’s a comedy, it’s a sort of underdog movie, which is a typical British movie in many ways. It looks very different to a lot of the other stuff that’s out there, that’s for sure, it’s got Nick’s sensibility all over it, and it’s really a story about a clash of cultures: cavemen, our tribe, and the bronze age, which is much more sophisticated. Fundamentally, it’s a slapstick comedy, really. It’s got a really lovely secondary character, Hognob, his hog, who is very appealing, and a little bit like Gromit, sorts out certain problems from his master Dug. It’s just a different genre, a different setting, and although we had films like DreamWorks’ The Croods, it just has a very, very different feel to it. Stop-frame animation obviously has a different feel and sensibility to it as well. Fundamentally, it’s a funny film, for all the family!

Trayton Scott: What is the message or experience that you want to deliver through this film?

David Sproxton: I suppose if you talk about the big messages: People get misunderstood, nations get misunderstood, don’t make assumptions about things. That’s really the big message here. Here’s this bronze age culture, they’re superior to everybody else, and actually it’s about teamwork, it’s about putting together, because what you really got is a tribe who are pretty rubbish. They can’t even hunt rabbits effectively, that’s all they live on, its rabbits, because they’re small, timid animals that they can just capture. So, it’s really a film about teamwork, working hard, putting together, to achieve something greater than the sum of its parts. Theoretically the big takeout in the film is collective thinking, I suppose.

Trayton Scott: From your view as producer, what makes Nick Park and Mark Burton such great storytellers?

David Sproxton: They both got a great comic sensibility. Mark comes from a comedy-writing background. Radio, TV, satire, in particular, he worked on Splitting Image, way, way back. Nick’s got this quite surreal approach to the ideas he comes up with, and strong characters. They get on pretty well.

Mark’s very good, over the years he worked on a number of feature film ideas, and he’s very good on the bigger story arc, and keeping you on track with that. And that’s something we needed on Chicken Run, and we got that with American writer Karey Kirkpatrick. His task was “guardian of the story”, as we called it, because you know, you tend to “Oh, do a gag here, do a gag there”. And as you’re writing, which takes years, and the whole process of feature films is about five years, you can go offtrack if you’re not careful, and Karey’s job is “No no! We’re doing this, because this is the story we’re telling, so we gotta get to there, we can’t go over here”, and Mark’s pretty good about it as well.

So you want somebody that’s what we call a structural writer. A lot of animators are very good on shorter form, or comedy, and character, and little sub-pieces, but you often need to bring somebody who’s a much more structured writer, that brings a 3-act structure, with what needs to happen at these various points, and keeping on track. They both respect each others’ point of view, and they’re aiming to get the film the best they can out of their work.

Trayton Scott: In recent years, stop-motion films are facing a renaissance in the global animation industry, with films such as My Life as a Courgette, Kubo and the Two Strings, and Isle of Dogs, and they are becoming popular topics of conversation. What do you think is the strength of stop-motion animation for storytelling?

David Sproxton: When you’re writing a script and you’re delivering it in a stop-motion way, there’s a tangibility to what you see on the screen. Everything’s is physical, that the audience responds to, and it’s not computer generated. And CGI is fantastic, we can do fantastic stuff with it, but for most people, for example, if I sat at home with a laptop and made a CGI film, firstly, I couldn’t do it, and secondly, It would take me literally decades to do it. Whereas with stop-frame, you could sit at home with a camera and make a film, and I think the audience subconsciously probably recognizes that, that they could do that. What you’ve also got, is quite individual visions. I mean Isle of Dogs had Wes Anderson’s look, that’s his schtick, that’s what he does, everything is very personal. The bigger CG films, the studio films, tends to be more of a committee driving those, and they look a bit more generic. Characters tend to look the same because the little kids want characters with big wide eyes, so they’re tending to come out of the machine, looking the same.

There are a few standout CG ones, but, with the stop-frame stuff, there’s a very individual look to them, although it is like a studio, whether it is Wes Anderson, whether it is us, and My Life as a Courgette, which I thought was a very moving film, beautifully made film, very simply made. It is quite low budget, should’ve done a lot better than it did, because it is an adult film, and a very very moving story, and I thought that is something where the images on the poster look quite naive, but actually the story is very sophisticated and really deeply moving. And that you can do, and it was surprising you can do that without limiting to shorts and everything. But I think it’s that individual vision, that individual look, that you get with stop-frame. Obviously you can do it with CG, but once you get these big films coming out with a hundred million dollars plus being spent on them, they become a little bit of a factory output, becoming a little bit more generic, I think.

Trayton Scott: What were the most challenging aspects of Early Man?

David Sproxton: Well, it’s got this football match at the end, and that’s going to be big, and actually, things like football and ballet are things you really don’t want to do in stop-frame, just because of the physical nature of the models, the speed of action, and all that kind of stuff, and in CG or 2D, you can stretch or squash, you can distort the models to carry the eye for fast action. It’s much harder to do that with stop-frame models.

So one of the big challenges was how are we going to shoot this, and what’s the scale. There is the arena with thirty thousand people in it, and we thought “how on Earth are we going to do that?” So it’s a lot of CG enhancements. That was the practical side. There’s always the challenges that we really have, because we know we can conquer them when they come, the practical production issues, we done enough of them to know the way of doing this. And the big issues on the way tend to be story-related issues, such as “How is this character working? What is this character? What sort of relationship? Is the protagonist strong enough? Is it funny enough?” Those are the harder questions to answer, because we got to dig quite deep and work hard to get those stories to really work. And when Nick came up with it, we thought he was crazy for coming up with a story with football in it, which is not normally done in stop-frame… But we done it, and it works really well.

Trayton Scott: Could you please let us know your favorite part of the movie?

David Sproxton: The hot tub sequence is just hilarious. That little sequence, where Hognob is massaging Nooth’s back, and the absurdity of seeing Hognob play the harp. It’s a classic bit of Nick. When you look at it, it is completely absurd. The way you get to it, is totally rational, but actually what the gag is, is just ridiculous and very funny. That’s a favorite sequence. Very nicely executed, very well timed. Very contained, it’s not a big action sequence, it’s a very contained, simple small-scale scene, that’s actually very very funny.