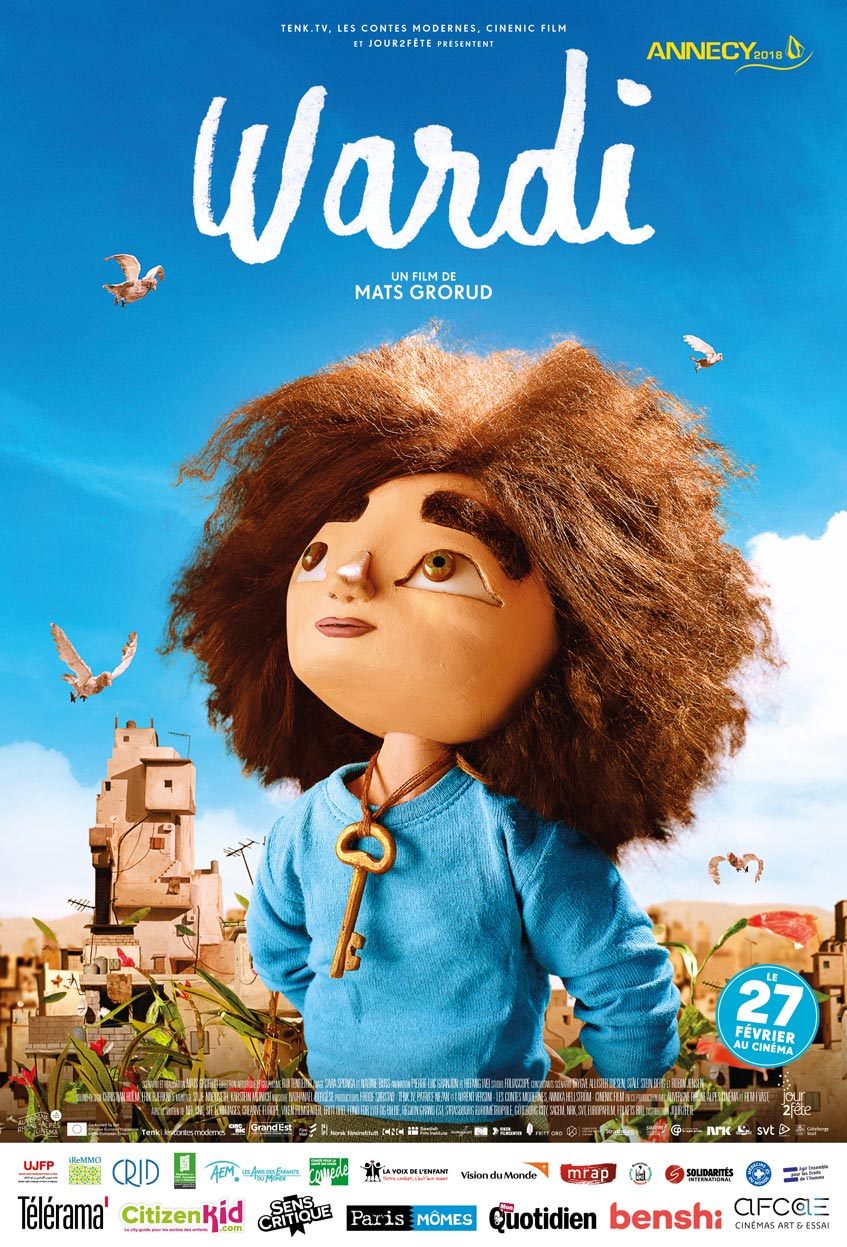

The Tower

Synopsis

Beirut, Lebanon, modern day. Wardi, an eleven-year-old Palestinian girl, lives with her whole family in the refugee camp where she was born. Her beloved great-grandfather Sidi was one of the first people to settle in the camp after being chased from his home back in 1948. The day Sidi gives her the key to his old house back in Galilee, she fears he may have lost hope of someday going home. As she searches for Sidi’s lost hope around the camp, she will collect her family’s testimonies, from one generation to the next.

Director: Mats Grorud

Scriptwriters: Mats Grorud, Trygve Allister Diesen and Ståle Stein Berg

Producers: Frode Søbstad (Tenk.tv), Patrice Nezan and Laurent Versini (Les Contes Modernes), and Annika Hellström (Cinenic Film)

Art Director: Rui Tenreiro

Animation Supervisor (Stop motion): Pierre-Luc Granjon

Animation Supervisor (2D): Hefang Wei

Animation Studio: Foliascope

Music Composer: Nathanaël Bergèse

The Tower is an animated film with both stop-motion and 2D animation scenes, which tells a story of the hope of Palestinian refugees. The events of the film were based on real interviews with Palestinian refugees in Beirut, Lebanon. A passion project from the director, this film portrays with great sensitivity the horrific reality the refugees have faced in their 70-year history, whilst always carrying their hope.

We interviewed Mats Grorud, the director and the scriptwriter, Rui Tenreiro, the art director, and Hefang Wei, 2D animation supervisor, at Annecy International animated film festival 2018.

Interview with Mats Grorud, Rui Tenreiro and Hefang Wei

Animationweek (AW): Where did the initial idea of the film come from, and how and why did you start the project?

Mats Grorud: When I was small, my mother was a nurse and she used to work in Lebanon during the wars in the 1980s, so I was always listening to her stories and seeing pictures from the camps of Lebanon. When I become old enough, I myself spent one year doing animation workshops in different camps and teaching English in the camp of Bourj el-Barajneh, in Beirut. It was a natural wish and choice for me to animate what I saw and experienced in camps, and the stories I’ve heard. This project started in 2001, and from 2011, after we had a production company, we started working on developing a script and characters, and financing.

AW: Could you please let us know a little bit about the making of the film? How did you develop the story, characters, and visuals?

Mats Grorud: The story is a hybrid between fiction and a documentary, so the development of the story took a long time to find the right balance between them to make the real stuff work in the dramatized film. It’s a written script based on my experiences and interviews, but the film itself is fiction, based on documentary sources.

In terms of the visuals, I worked closely with the art director, Rui Tenreiro. He is a Mozambican living in Stockholm, Sweden, and I really like his artwork, so we found our way. One challenge in the film was to combine two animation techniques, stop-motion and 2D animation. We needed to find a common visual style for the two techniques because we would make it into one film. We worked with a French studio, Foliascope, with Pierre-Luc Granjon for the stop-motion part and Hefang Wei for the 2D part. So, it’s a close collaboration with the three artists and me.

AW: How do you take people’s real experiences and translate that into film?

Mats Grorud: The two main animation techniques in this film, 2D and stop-motion, had a slightly different approach in each. I had a much closer relation with the stop-motion part, because it’s really about my experiences living in the camp and what was happening around me. And, with the dialogues, it was much easier to know what I wanted to show.

The difficulty of dramatizing it was finding the balance between how much should be documentary, and how much to make it into a movie that is engaging and draws people in, and letting the journey of Wardi be real and something that people cared about.

It was my first feature script, so it was quite a challenging task, but I had good help from the editor, the scriptwriters and the storyboard artists, who were really important to how I found the way.

The way of making the flashbacks in the film was a little bit different, because I didn’t experience them myself and I didn’t have much writing material for the scenes. So, I based it on interviews done in person or from historical sources. I tried to find the essence of a certain thing that I wanted to show, and fictionalize it with fragments of real things. I showed it by straying from the documentary part into the fiction part. Shedding some light into what is the truth in the story helps when you fictionalize it.

AW: How did you make the characters and events in the film emotionally convincing?

Mats Grorud: The only way I could make sure that we made something that worked was by letting the team bring their experiences. I realized early on that, if we want this film to be great, it’s not about my ego as a director, it’s about creating a space where the team feel confident and that the film is also theirs.

Although we had the storyboard, I was quite open to input throughout the process, working with Pierre-Luc Granjon and Hefang Wei, to see if our plan works.

I was open to both of the animators, and I found to come with their input if they felt there are ways that we can make it better. It was, until the end, quite a lot of work-in-progress. Even towards the end, we would change things, and Hefang would snap me out of it because we needed to make a picture we didn’t yet have!

AW: 2D Animation was used when the relatives describe their past. What was your reason of using 2D for those scenes?

Mats Grorud: I’ve used this technique before in my films, where I combined drawings for some scenes and stop-motion for others, so for me it was a natural choice. It is also a practical choice, such as in recreating the camp in the historical space of Beirut in the 50’s and 60’s, at different stages in time.

We felt the 2D drawings gave us this tool to be connected to what was real. We could easily draw details based on references and how things looked. It gave us this chance to be close to reality, which is what we wanted for the film.

Since I was collaborating with Wei, it was from early on that her style had the visual language I wanted and it was important for the film, so I brought her onto the project and see if we could do something unique for our film, based on her quite graphic style, and to have the peers’ input on the stop-motion and 2D world.

We wanted the flashbacks to not just feel like a history lesson, we wanted to try and explore the psyche of what happens to people in war situations, and we felt that the drawings made it much easier to visually base from. We have the visual freedom in the drawings to go to where we want. With the puppets, due to their physical nature, you are more stuck.

So, for a number of reasons, we felt that the drawings were a good direction to take.

AW: We would like to ask three of you about your personal impressions about the completed film.

Mats Grorud: It’s a bit hard, because you worked so long on it. Of course, I’m happy with it, we had three screenings here in the festival, and people are really moved, but it’s not about my impression, it’s their impression. I’m happy it works in many ways, because I wanted two things: I wanted to move people, and I want to help somehow explain people’s lives, and I think now people understand and feel a little bit more.

I think overall we managed to reach our artistic goals for the film, and the film in the end became more than I hoped for, because the process was quite open as I said, I wanted input from the team. I was not afraid to open up my vision, which was very personal to me, because I felt the whole time that we kept the soul of the film. it was always there, so it was just having different ways to show it, and the team really helped me find those ways.

So for sure, the final film, as it is, is really a team effort. When I see it now, I’m touched by different kinds of scenes, and I’m a little bit surprised sometimes by what touches me. It is up for others to see it.

Hefang Wei: When you walk out of the film, it’s difficult to distance from it in a short time. When we watch the film, we remember so many details, and there are some problems that we wanted to solve, but we didn’t have time or there’s some other limitation. We know that every film we made had some limitations.

I guess you showed me three times on a small monitor when you were still editing, and it is different when the picture is on the big screen and the sound is around me. We were working on the film piece-by-piece, and now it becomes whole. We watched the completed film a few days ago with another animator from the team, and we felt so much emotion from it.

I’ve never been to Palestine and Beirut in Lebanon, but personally, I feel a bit like I travelled in the past, it’s like a story that you told about all those people in four generations in the film. It’s been almost a year after we worked on it, and we were talking about the acting, the feeling of the people. Now when the film finished, it all becomes true and real for me. I almost feel like I met them in the film before, so I would say that’s the power of this film project.

Mats Grorud: I had to tell the part of the team that haven’t travelled to Beirut how it looks, and what the stories are of people, to try to make them understand as much as possible. It’s not so easy, but we managed. I’m happy for that.

AW: Generally, this animation is dealing with a really difficult issue that’s still ongoing, and of course, much of the audience still hasn’t seen the reality, so it’s like a really big conversation from you to the audience.

I just wanted to know the difference between typical animation for entertainment, and an animation that has a really strong message, including the attempt to portray the world that we share, and giving an opportunity to think about that issue.

Hefang Wei: I personally feel that Matz has a strong message in this film. It’s not like some other films that seek out a new way of showing pictures. It’s not about the clothes the people are wearing, but the people themselves. It’s more direct, but sincere.

It’s funny that we make a film that has a message Mats want to pass, but somehow Mats put himself into the film.

Mats Grorud: When you want to tell something, strongly, you have to find this balance where you’re not overtelling or showing too much or showing it all the time. It’s our first feature, so we were trying to find exactly this balance: what works, what is too much and what is too little. It is finding the balance where it is subtle, but at the same time, you should not be afraid to show things. I hope we’ve achieved that with the dialogue and the script, and the way we made the scenes and graphics.

Since what we wanted to tell was so much and so strong, maybe some things come out very strong, maybe some things come out slightly less, but perhaps that’s okay. I mean, you can tell a lot, but within an hour? We’re trying to tell a story, which spans over 70 years, with 40,000 people living in the camp, that’s four generations of people! It’s a lot to talk about.

At least, some of the most important things, which is about showing people as people, comes through in the film.

AW: What do you think is the power of animation for telling a factual story?

Mats Grorud: This is a specific story about a specific situation with specific people: the Palestinians being refugees. But I think that, by animating it, you hopefully draw the audience to place themselves into the story.

I think when you choose a medium that people can relate to, they don’t think that it’s just people they don’t know from far away, but instead see somebody that they can relate to in a different way. I think choosing animation can make something universal, and hopefully make people become empathetic to the story in a different way. That way, it is not about them, it becomes a story about us, because the characters and the puppets could be me and they could be you.

Apart from that, animation allows for a different kind of dialogue, and it allows more freedom, which gives you many chances to make people react in telling your story. I think when people see a live action, they have strong ideas on what it should be, since it’s so real. If the dialogue is a little bit strange, they will immediately be put off, they will not relate to it, and they will come out of the story. With animation, the language of the film gives a much wider range of what you can say and how to say it.

Hefang Wei: In animation, you can choose what you want to show, but in live action, you have to use actors. There are some little details you cannot have 100% control over, whilst in animation you can choose some details you can show, and omit the ones you do not want. The language is more selective.

Mats Grorud: Right, but I don’t think people have this filter in animation that they would have in live action, because live action is old; they know it.

AW: So, if people watch live action, they feel that it’s a story of a totally different person. If they watch animation, they can dive into the world and immerse themselves into the atmosphere of the people in the story.

Mats Grorud: I think so.

The stories were based on a lot of interviews I did with my friends, and we spoke in English. The English was broken, but I sometimes felt that it become very poetic how people would talk, because Arabic is a very rich language: When they talk in English, and they translate from their mother language, Arabic, in their brain, many times it was beautiful.

There were sentences said that were fantastic. I wanted to bring some of that into the film, and I felt that you couldn’t say it with live action, but it works with puppets, because you don’t have this filter on whether something feels unnatural.

AW: Let us know the design process of the characters in the film.

Mats Grorud: We had Rui’s design for the 2D parts from a very early stage, but then he was working on his graphic novel, so at the time we were developing the puppet part in Poland.

Then there were these beautiful puppets that we made in Poland, but there wasn’t yet the link between the 2D and the puppets. So, in the development stage, not that we were unable, but maybe we were not conscious enough of how we were going to combine the two worlds, so they turned out quite different.

After Rui finished his graphic novel, Lanterns of Nedzu (which is a beautiful book!), we were able to sit down and figure out what should we combine in the 2D and puppet part for the character design, and we found some rules: We needed some strong visual links that you immediately understand. For example, having something just be the 2D version of the puppet world. We found, and I call it Rui’s “beautiful ugliness”, that I’m really fascinated by these beautiful drawings that are a little bit ugly, and I think the eyes, the shapes of the eyes, the mouths, and the nose, were very characteristic.

We wanted something that was unique to this film, and we didn’t want something that was too polished. I find that a lot of animated films based off illustrations just come out of the machine of animation companies. It becomes slightly boring, because it’s too polished, it looks too nice, and too beautiful, and you’ve seen it before. It takes away the uniqueness of what you had in the illustrations.

To transform the 2D elements to the puppets, we drew some lines instead of seams, and the characters have quite outlined eyes. We wanted to keep the beauty and physicality of the puppet world with the textures and the details of what’s real, so we had to find a step in-between, with some things being two dimensional in the puppet world, but not too much.

Hefang Wei: For the 2D part, Rui’s personal style is really flat, the line’s really smooth, and he uses flat colours, then he puts textures, which makes the 2D a powerful contrast against the realism in the puppet, which makes it feel quite close to reality for me.

Rui Tenreiro: I think there’s several things that you want to say in the film because, as you say, you have a lot to say. But I think one of the things that you wanted to do was to humanize refugees, not just make a political film about something far away. Mats worked with a subject that was very close to him, which was people that he knows, directly, and he sees those people.

When we talk about refugees, or people that we don’t know, it tends to be this abstract, distant thing, and one of the tasks of working on the visuals was to provide a human face to the refugees. Not just to present it as something that is suffering and that is far away, but something that is close to you and that is human, and that consists of real people Mats knew and lived with for one year.

Mats Grorud: Still now! It’s not just the past, I mean all these people are still in the camp. Some left, like one of my friends, who’s now in Sweden. These people are still there. It’s about people, that’s the main thing.

In interviews, I’ve heard things I’ve felt were really strong and powerful, and one of the things an interviewee told me was: “You know, in the end, Jerusalem was just a city. Let these children play.” It’s not that Jerusalem is not important, but his message felt very strong. Come on! We are 40,000 people living here, and this doesn’t work, it’s not fair. People should be allowed to live. That’s it. Let people live a dignified life, and this is what we wanted to show in the film. What’s the dignity that people do have? It’s just how you portray people.

Rui Tenreiro: Speaking about portrayal, when we were developing the animated characters, one of the things that Mats kept on telling me was: “You know, these people have nothing. They have some things, but they have very little, and they take what they can get to have their daily life”, but there is another aspect, which is that they carry themselves with dignity, and they have a sense of belonging to a place that is dear to them. Their origins that has been kept alive through spoken history.

One of my tasks was to carry that through the image of the characters. Not just throw some clothes on, but to present the design of the characters in a way that would be beautified, to beautify Palestinians. Maybe someone has a sense for style, and some guy likes to wear flip-flops. People have different choices, just like the people in the camp.

To represent the people of the camp, we also worked hard to not represent stereotypical Arabs. The Palestinians have come from this land that throughout history had people come from all over the world to what was called Palestine. There are Palestinians who have green eyes and who have brown eyes, including different shades of brown. Some have reddish hair. You find that it’s not just this mass of people that all look the same, it’s really diverse. I hope we managed to show that.

It’s also the image of the refugee, like with torn pants, etc. People don’t have that. It was a difficult task to show people living in a difficult condition, and at the same time, showing that they wear very nice clothes. But then, when people see the film, they feel that there is no problem in the economy, since they look so nice. It’s the same with then camp; people hate the camp, in some ways, and at the same time, they love the camp, it’s their home. But they’re stuck in this really, really bad situation in exile, forever as refugees through generations. Still, it’s their camp, their home. They have this other home that they were forced out of, which is so important to their identity. These were all the things that we wanted to show in the film.

AW: So, what I thought after listening to your story of making the visuals was that people tend to have visual stereotypes of everything, but when people watch the film, the audience would not see those stereotypes with the characters in the film and instead relate to them. For that, you took care a lot not only the storyline but also the visuals, right?

Mats Grorud: Sure, but also, for example, we did the same with the music to find a balance. I love Arabic music, but if we had a soundtrack that was very Arabic-sounding, it could, or we thought it could, make people think “Oh, it’s a film from the middle-east. It’s not something that it’s about us.” So, we wanted to find a soundtrack that made people relate to the characters. So, it does have oriental scales, but it’s also European music or a classical approach.

Hefang Wei: Because those two kinds of music have different functions. You have Arabian music for the Palestinians. That kind of music can make you feel that you’re there, but that is not enough to let the director or filmmaker show the context of the scene, so you can put another group of music that highlights your feelings or allow the audience to understand.

Rui Tenreiro: It’s true. I worked more visual, and you guys worked more in a directorial capacity, and you’ve worked together to make the characters have emotions so that you know to make the characters have a response, an emotional response on the screen. So, you guys more-or-less collaborated in directing the drawing, if you could say the drawn actor, to have an emotional response, which is separate from what I was doing. Connected in some ways, but not totally. It was more directorial decisions. It was just interesting to see.