Behind the story of Pokémon :

Meeting the Challenge of 2D digital production with care, passion and a meticulous attention to detail

<Part 1>

[row][column size='1/4']

[/column]

[column size='3/4']

OLM is the animation studio that produces and animates every series and film of the world’s hugely popular franchise Pokémon and Yo-Kai-Watch. OLM began using Toon Boom Harmony in 2015 and took the lead in 2D digital animation in Japan. Since then, the OLM team responsible for facilitating 2D digital animation has worked hard in developing original manuals and accumulating know-how on methods of 2D digital production.

On the Japanese 2D animation production scene, the transition from the traditional production process with pen and paper to a 2D digital production is of growing interest. Moving to 2D digital production opens up the possibility of the Japanese 2D animation industry co-producing with studios overseas. The Animationweek Editorial Team sat down with the production team of Pokémon at OLM to hear about their efforts and challenges in transitioning from paper to digital, the merits of 2D digital production, and plans for future development. Throughout the interview, the three most notable things that stood out were: 1) a strong passion for the audience and working in animation, 2) professionalism and an aim for perfection such as getting a single digital line exactly right, and 3) close internal and external collaborative relationships.

[/column]

[/row]

A Challenging digital production with Toon Boom Harmony

Animationweek (AW): How has OLM decided to pioneer 2D digital animation production in Japan?

Hiroyuki Kato (HK): We had a regular internal meeting right after the New Year. At the first meeting in 2015, we announced that we would start digital production, so the usage of Toon Boom came down to us making a decision. There are different kinds of 2D animation software available, such as TVPaint, Clip Studio from Japan, and Toon Boom Harmony. We decided to use Toon Boom Harmony, including a pilot license, as our starting point.

I am in charge of Pokémon, but OLM has other titles such as Yo-Kai-Watch, among many others. It is up to each producer’s discretion on how to introduce digital production. Practically speaking, the first step my team took was trying out new equipment before thinking about the workflow or production pipeline. It was very confusing at the beginning as there were a lot of things that the creators, who normally work with paper, did not understand. With so much flux, I tried to find our own way of handling the concerns by discussing different approaches with Ogawa from the keyframe and layout team and Murooka from the drawing and in-between checking team. Within a month of introducing Toon Boom, it almost felt like we were facing a historical moment similar to the arrival of the black ships of Commodore Perry from America in 1853 for the opening of Japan, which had a closed-door policy then.

Establishing the workflow with Toon Boom Harmony

AW: You eventually established your workflow with Toon Boom Harmony. How was this achieved?

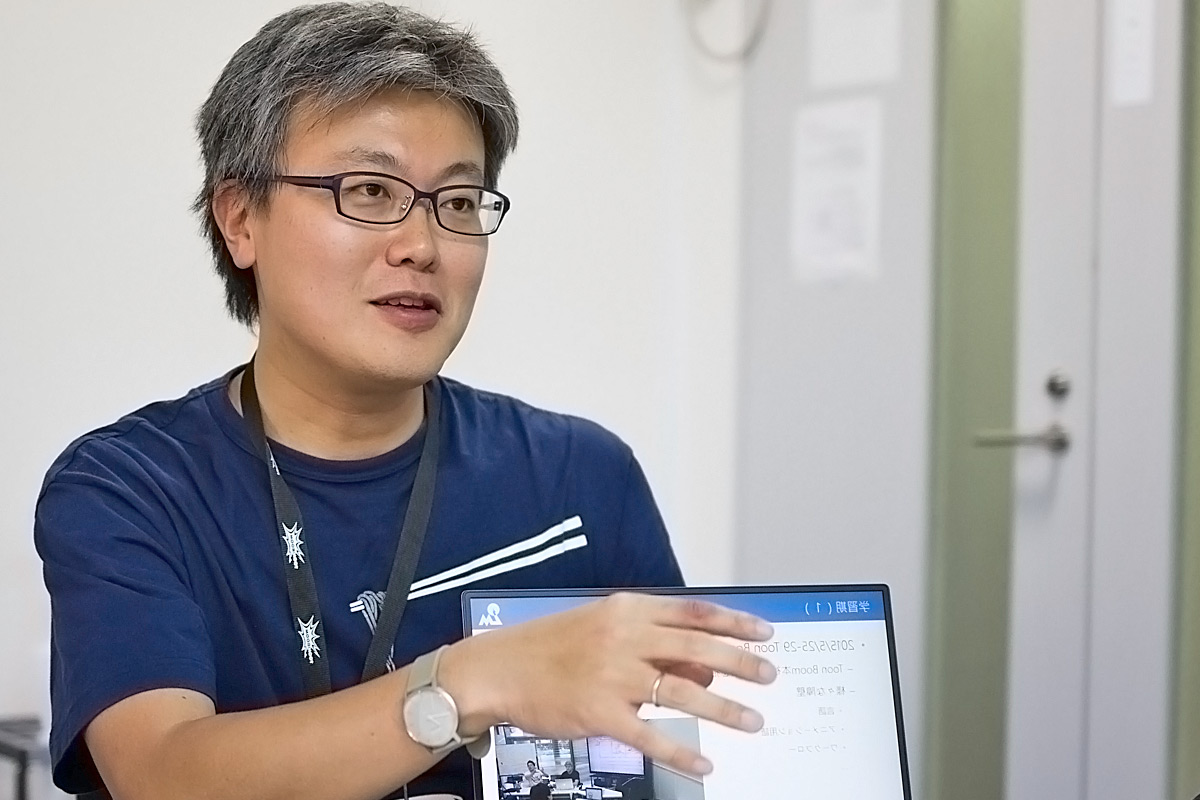

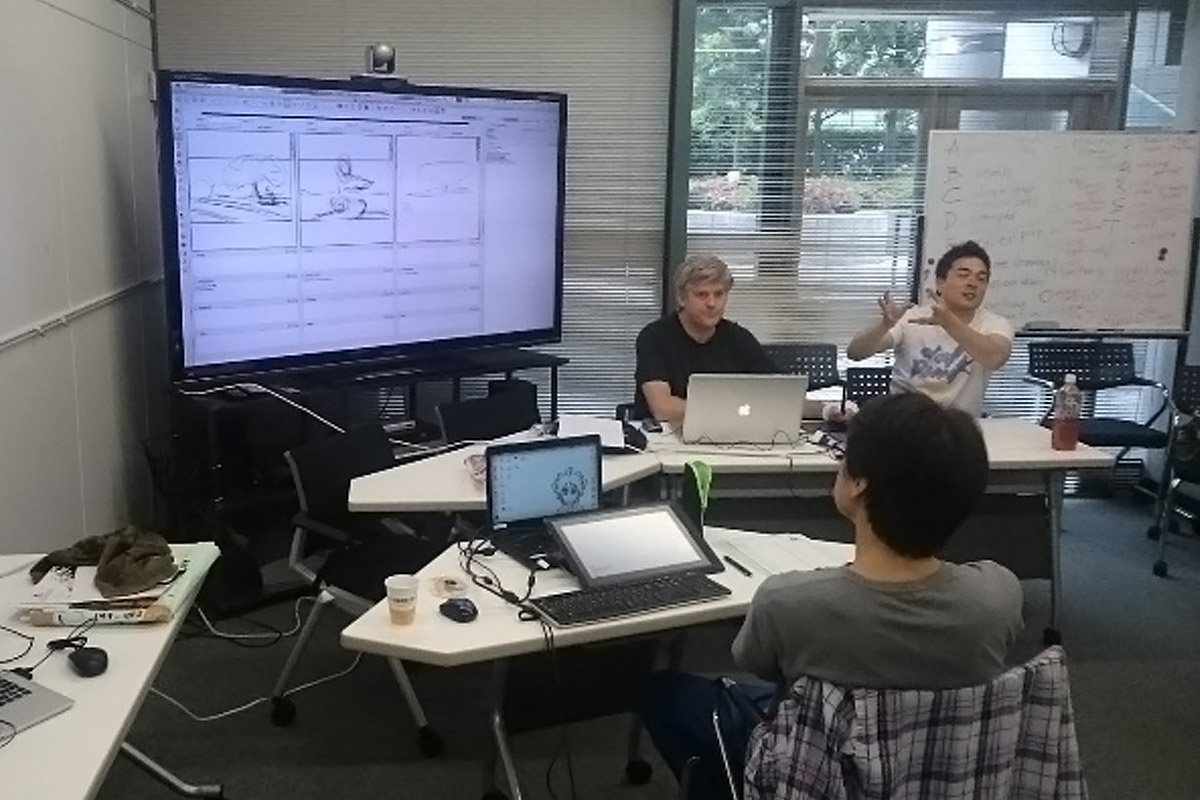

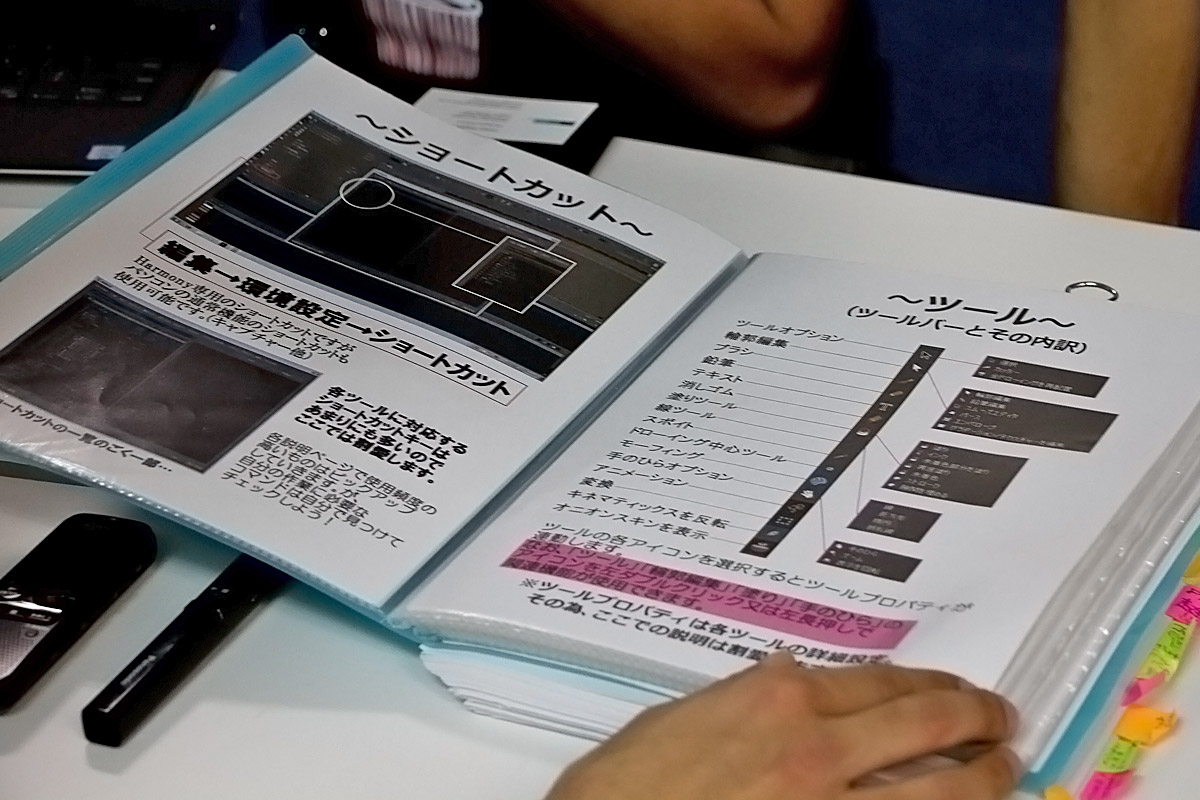

HK: In fact, we asked an expert staff member from Toon Boom to come to Japan in May 2015 as a lecturer. Our team was then able to ask him questions directly, however we were still confused as the principles that guide the basic production workflow in Japan are totally different than those for the West. This made communication with each other difficult, apart from the language differences between English and Japanese (picture 1).

Tatsuo Yotsukura (TY): Yes, we did not understand English animation terms at all. For example, how were we to translate the word ‘genga’, a Japanese word that is roughly equivalent to the English word ‘keyframe’? It was a challenging process.

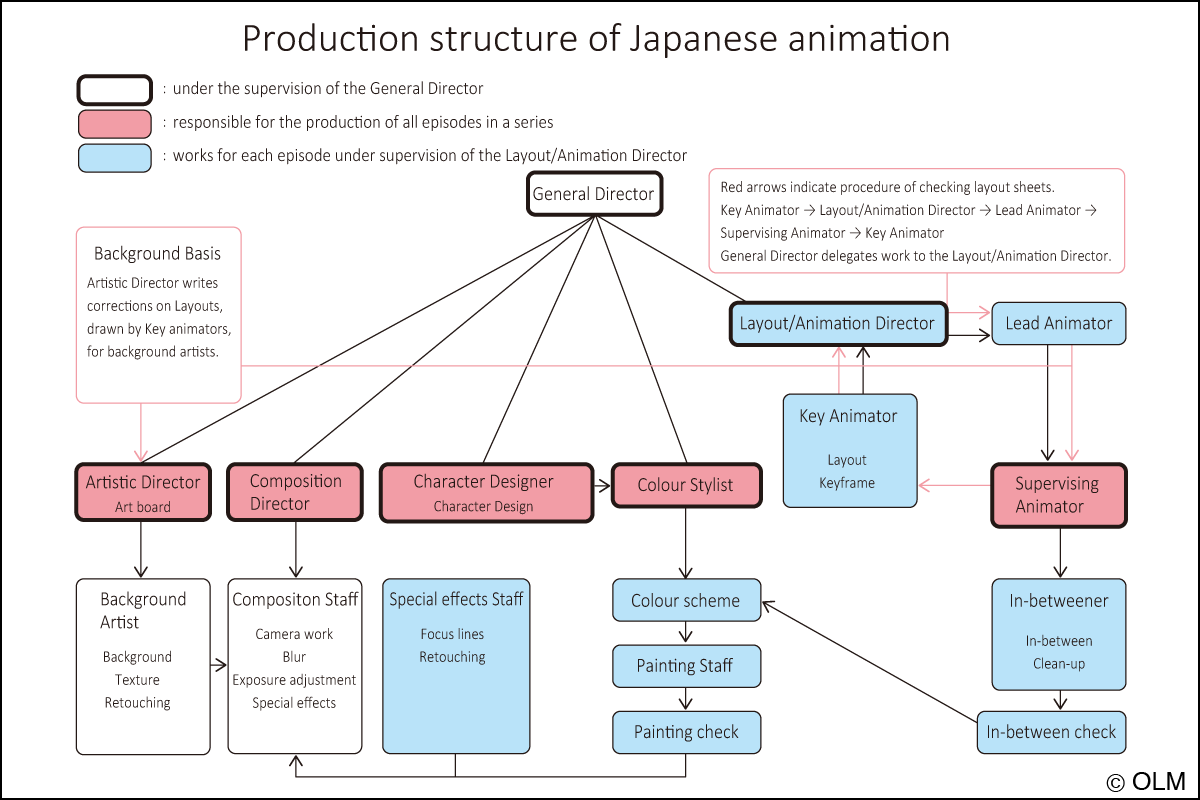

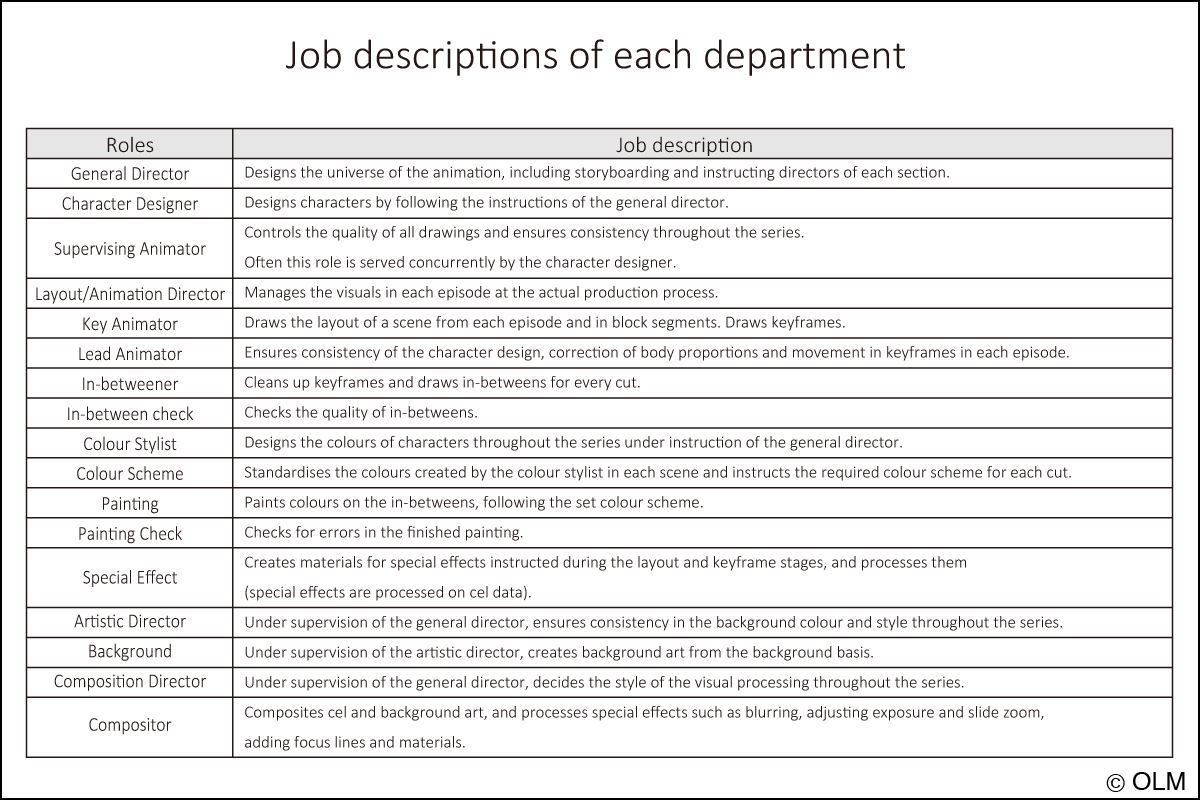

Shinichi Murooka(SM): The lecturer stayed in Japan for a week. We spent a full day finding a common ground for a production workflow between Japan and the West (figure 1 and 2).

TY: The R&D department in OLM Digital, to which I belong, is in charge of providing support for the PCs and licenses of Toon Boom Harmony that are used in digital production. I gave the Japanese version of the Harmony User Reference Guide to our creative team members, but they weren’t really able to use it intuitively as it is really meant to be a reference book providing extensive coverage of the software. We decided to develop our own manual.

HK: It is very hard to index with the original manual.

SM: It is also very time consuming for creators who are actually working to read this manual to do their task. We wanted it to be as simple as possible.

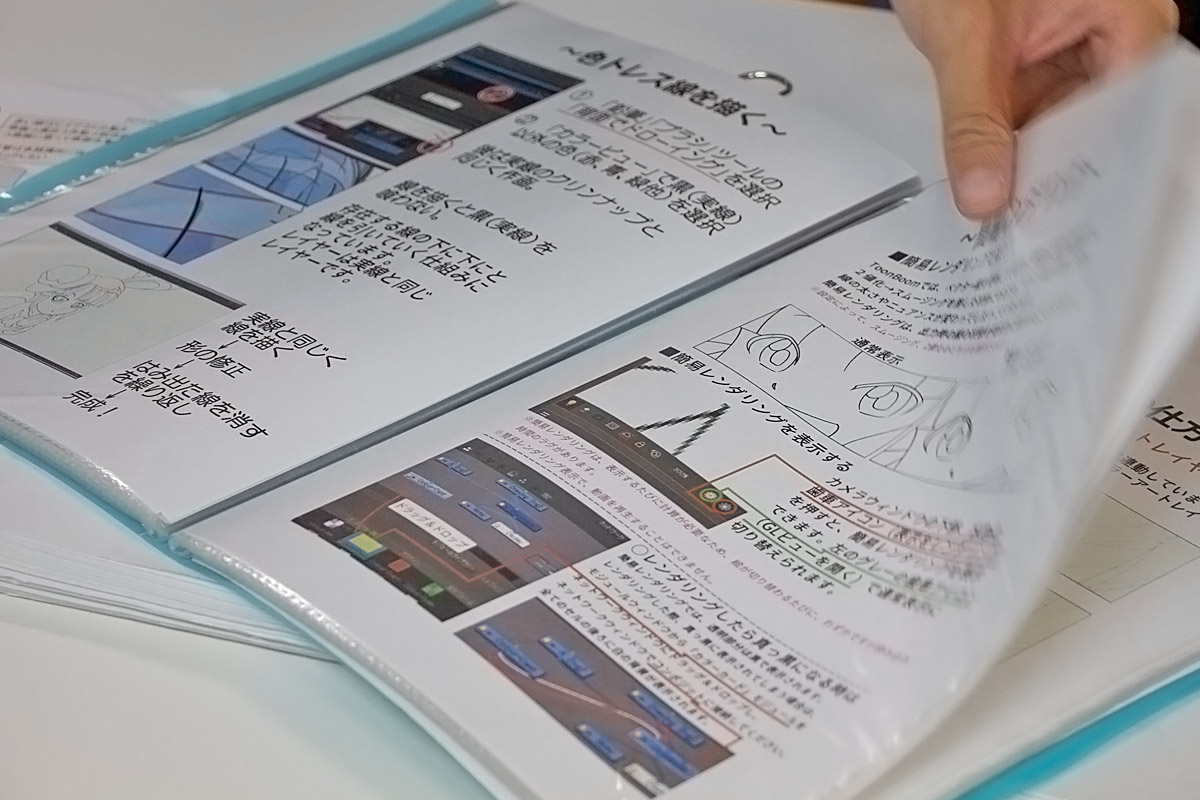

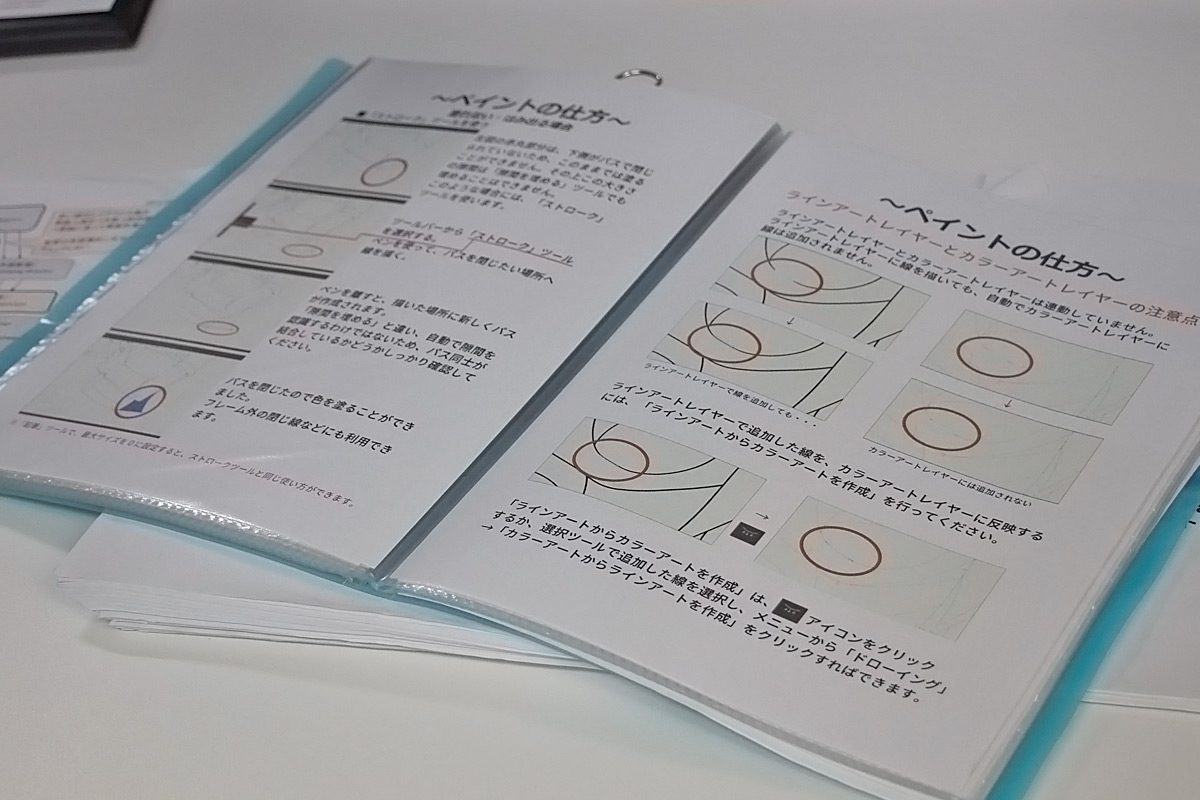

HK: Yes, it was quite difficult for us to understand the basics with the original reference guide as the method we use in Japan to produce animation is totally different from that in the West. So we wanted to create a manual that would work for us (Picture 2-4).

[row][column size='1/3']

[/column]

[column size='2/3']

AW: This manual that you made follows the workflow and timeline of your studio. A creator can find the exact item that is relevant to their working task in this manual easily and quickly. For example, they can look it up in the manual and say, “I am just in the process around here. And it looks easy to read with a lot of pictures”.

TY: We also keep adding new information to these manuals. For example, we now have information on shortcut keys. People can download this manual for free from the Daikin-Kogyo website here: (http://www.comtec.daikin.co.jp/DC/prd/toonboom/tutorial.html). Daikin-Kogyo is the retailer of Toon Boom in Japan.

[/column]

[/row]

AW: It must be really helpful for other Japanese studios when they want to introduce Toon Boom.

TY: Yes, we hope that our manuals will help others in Japan bring Toon Boom Harmony into their studios.

We are also going to release a manual on camera work in the coming weeks. The manuals you see here are on in-betweens and painting. When you produce animation, you draw layouts and keyframes. So it came to us as a question: “what are we going to do with camera work?”

HK: We feel that this will be like a how-to book – to show you how to draw layouts and keyframes in animation. Our process for creating the manual is now in the next stage, applying from the first step of the tutorial. And, the English version of our manual on camera work could be welcomed in the West, because it enables them to learn the unique camera work of Japanese animation.

[row][column size='1/2']

[caption id="attachment_5029" align="aligncenter" width="1200"] Picture 1: A workshop with an expert staff member from Toon Boom[/caption]

Picture 1: A workshop with an expert staff member from Toon Boom[/caption]

[/column]

[column size='1/2']

[caption id="attachment_5045" align="aligncenter" width="1200"] Picture 2: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

Picture 2: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

[/column]

[/row] [row]

[column size='1/2']

[caption id="attachment_5046" align="aligncenter" width="1200"] Picture 3: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

Picture 3: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

[/column]

[column size='1/2']

[caption id="attachment_5047" align="aligncenter" width="1200"] Picture 4: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

Picture 4: A manual created by OLM[/caption]

[/column]

[/row]

Application in a commercial animation production

TY: Little by little, our learning produced better and better results, and so we said: “Shall we try practicing it?”

HK: We started by animating one short. Through this experience, we were able to confirm that the current animation production workflow could be replaced with Toon Boom Harmony. We moved on to produce a film that would meet the standards needed to broadcast on TV. You see here the first project that we challenged ourselves with, which is a very short film. Video 1 is an animatic with just lines. Video 2 is the film with colours, and Video 3 is the final film with effects applied.

[row][column size='1/2']

Video 1

[/column]

[column size='1/2']

Video 2

[/column]

[/row] [row]

[column size='1/2']

Video 3

[/column]

[/row]

TY: We created every part of this film with Toon Boom Harmony, version 11. Now we are using version 12*. Version 12 has better additional features on compositing. We have sent requests to Toon Boom that we think will make it even easier to use Harmony on a Japanese production. I just would like to note that we used Adobe After Effects at the last part of video 3.

*The latest Toon Boom Harmony as of 23rd August 2016 is version 14.

HK: When we created this short film, we used After Effects to create the same quality as the Pokémon animations that we had made using the traditional method of drawing on paper, because we wanted our end users, children, to watch our animation and say: “Yes, it is Pokémon”. But now we can replicate almost the same quality visuals as the current Pokémon series and films using only Harmony version 12.

AW: It’s impressive that you have already reached to this stage, considering that the project only started in January 2015. You were fast at setting up the system.

SM: I started the project with only Ogawa in 2015. After 2-3 months, we got a new member. And then, three additional members joined us and we grew gradually, until the number of staff had doubled. When our team was small, we were worried and wondered: “What is going to happen?” But, the number of things we were able to do increased as the size of our team grew.

AW: Has the film, which you produced digitally, been on air?

SM: Certain scenes have been aired but we only digitally produced selected animations, the ones we thought would actually work. Rather than producing a full episode digitally, we underwent our transition to digital production with extra, very short animations for the TV program Pokémon, such as those we showed you now. As the main episode is produced with paper, we have begun a trial that we use paper to make layouts and keyframes and then move onto digital, starting from the in-betweening stage.

With great care for a line (A mark of strong passion as a creator)

AW: It is hard to identify the difference between an animation made with hand-drawn keyframes and the fully digital animated work I just watched. Did you have any difficulty reaching this level or do you have any tips that you learned throughout this journey in digital production?

SM: When you scan a hand-drawn line drawing (keyframe), there is a certain level of unevenness. That kind of unevenness may work fine and sometimes results in a good character for the final visual. On the other hand, the basic vector line of Toon Boom Harmony was sometimes too smooth, and seemed too clean for us. For the experienced hand-drawn animator in Japan, it felt too clean, like industrial engineering product design. So, we tested a scene a number of times, inserting an image drawn with Harmony into a traditionally hand-drawn scene in the TV series to see the level of difference between the two. Through these trials, we were able to reach a finished quality in Harmony that we could say: “this is acceptable”.

HK: We compared different patterns of line width and whether to use pressure sensitivity. We needed to create test material first, and then we used that same test material repeatedly, five and six times. In all, it took us about one month to find the optimal vector line settings in Harmony.

TY: Here you see an outline test (video 4). Can you see a difference in line widths in these 6 patterns? It took about a month of adjusting to achieve the perfect line.

[row][column size='1/2']

Video 4

[/column]

[/row]

SM: We first created one illustration, then we created several different variations from the illustration by changing the vector line settings in Harmony and seeing whether the lines were too thick or thin. We tried thickness values of 2, 3, and 4. With a value of 2, it is too clean and looks thin. If a value is more than 3, it is too bold. So we set it to a decimal point. When we did the test, we changed only the thickness of lines and turned off pressure sensitivity so the thickness of the line was what changed from the start and end of the stroke, in effect simulating pressure sensitivity, so that we were able to only compare the thickness of the lines.

After comparing line thickness, we turned on pressure sensitivity and repeated the same trial. Then we decided on the line settings: 2.5, with pressure sensitivity. The line for the nose looks a little too even without pressure sensitivity.

One additional thing I would like to mention is that you can reduce or emphasize the width of the beginning and end of a line, which reflects your pen stroke and pressure. At first, we thought it might be better to not set line width variation at the beginning and end of the stroke. But, we found that the finished line became just a line without this functionality, so we decided to use this feature.

AW: By looking at the eyelashes carefully, there is a certain difference between lines with stroke width variation, and without it. For me, it gives the impression of gentleness.

SM: It was necessary for us to increase the visual quality to a level that would enable the audience to discern the small details of the finished illustration. It was essential that we didn’t deteriorate the quality of the illustration that had been hand-drawn by a keyframe artist at the cleanup stage, after in-betweening.

Not letting audiences feel the ‘coldness’ of digital production

[row][column size='2/3']

HK: I think that it depends on the type of animation work. Our work is created with limited animation, which is common in Japanese animation and different from full animation. If you are doing full animation, you may not notice the loss of the natural quality of a digital cleanup drawing made from a traditional sketch. However, if you are producing limited animation with digital line drawings, it looks too clean and the movement of character animation looks stiff. We adjusted our digital cleanup drawings to have line width variation at the start and end of a line to replicate the look of a traditional drawing on paper as much as possible, and to give a hand-drawn feel.

[/column]

[column size='1/3']

[/column]

[/row]

To tell you the truth, a similar thing happened when we moved from colouring on cel (celluloid) to digital colouring. People at that time were seeking a way to re-create a cel-like digital image on the screen because, when they compared the cel image with an image that was painted on a computer, they felt that the cel image gave more warmth to the audience.

Then, they added a filter onto the final image to create visual noise, which we called “adding gauze on purpose”, which evoked the impression of a cel-like image rather than a digitally coloured image. The filter effect was subtle, and we reduced the amount of noise gradually, at a pace that our viewers could get used to the change without noticing the difference between a cel colouring and a digital colouring. Now, we do not use this kind of filter at all.

I think now is the time to transition from analog line drawings to 2D digital line drawings. We are conscious of the expectations of our end users during production, and are passionate about meeting them using these kind of tests on line drawing settings with Harmony, as well as using filters with After Effects. Some people may find it a lot of effort and the long way around. But, we have a strong passion in film production.

Edited by Animationweek and Toon Boom

Photos by Aya Tanaka