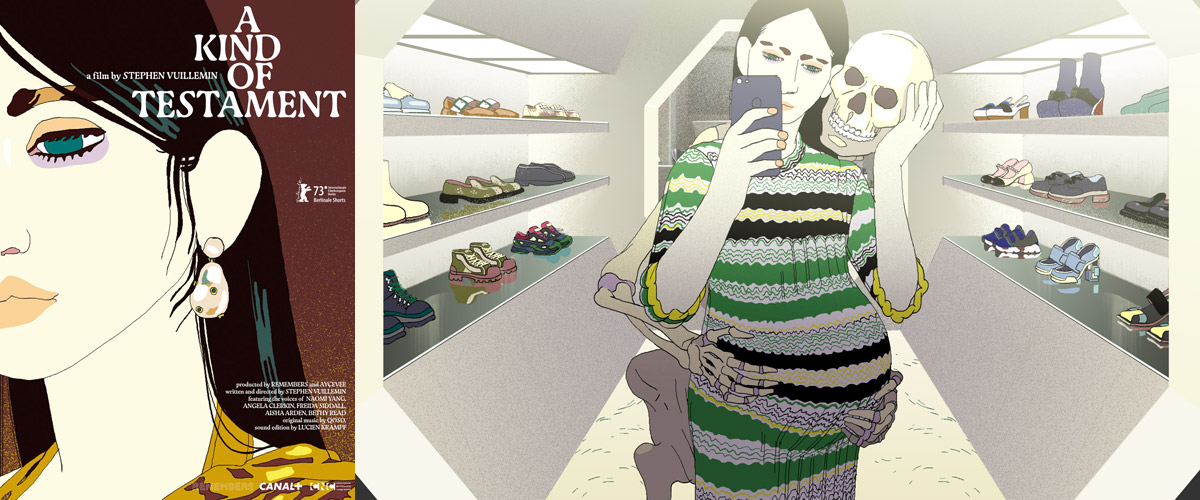

Synopsis

A young woman comes across animations on the Internet that have clearly been created from her private selfies. A stranger with the same name confesses to identity theft. But death is quicker than the answer to the question: “Why?”

Film Credits

Director: Stephen Vuillemin

Production: Remembers

Screenplay: Stephen Vuillemin

Music: Qoso, Jack Willie

Animation: Stephen Vuillemin

Running Time: 16 minutes

A Kind of Testament is a film that depicts both conscious and unconscious intentions behind an anonymous person’s desire to transform, using the power of animation as a visual storytelling medium in a novel way.

By using the issue of privacy in social media as a stepping stone to the film’s philosophical narrative, A Kind of Testament gradually immerses us to a fake, animated world where we are unleashed from the persona perceived by society and experience the inside of one person, told with limitless visual expression.

The film has been getting numerous nominations/awards internationally, including the Zlatko Grgić award at Animafest Zagreb 2023, the Best Short Film (Gold) of the Axis (Satoshi Kon Award) at Fantasia Film Festival 2023, and the nomination for Berlinale Shorts at the Berlin International Film Festival 2023.

We interviewed Stephen Vuillemin, the director of A Kind of Testament.

Interview with Stephen Vuillemin

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): What was your main aim in developing this film?

Stephen Vuillemin: I wanted to make the best film I possibly could. I was working in London at studios mainly dedicated to advertising and special effects, and I wished to create something more personal, outside of that somewhat stifling environment. So, I started making the film all by myself, in my free time, without thinking about how much time it would take; the goal was truly to do the best possible job. At that point in my life, I did everything to advance the film – I took on as little freelance work as possible to have more time, and I left London to move to Taiwan, where I could really focus on the film. After 4 and a half years, when I had returned to France, I received the support of Remembers Studio, an incredible studio run by artists, which helped me finish the film with a team and some fundings. In the end, it took 6 years for a 16-minute film, but I’m 100% satisfied with it.

HN: Where did the initial idea of the film come from?

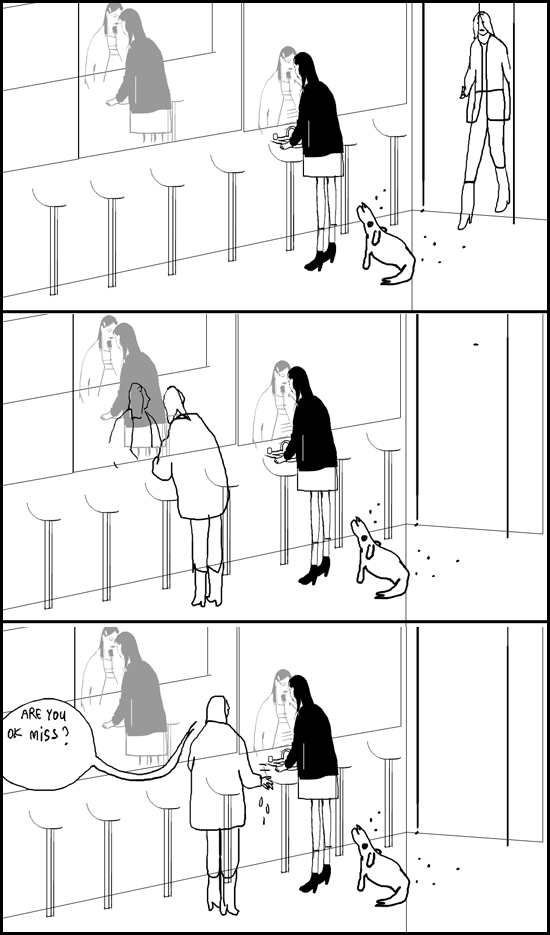

Stephen Vuillemin: My initial ideas didn’t concern the story, but rather the medium (I’m a big fan of the motto “the medium is the message”). I wanted to work with a voice-over. I also wanted to create a very rich film, from all perspectives. I had the concept of “found-footage” in mind, thinking that the voice-over could add a different layer of meaning to the visuals.

When I was doing freelance illustration in London, I received a commission from a big American startup. They wanted to give some of their staff a special gift: personalized animated GIFs in their liking, that I would draw and animate. It was meant to be a surprise, so I couldn’t tell them about it, but I still had to draw their portraits. So, I used these peoples’ Facebook profile pictures as a reference. I drew them, and then added moving elements, that weren’t in the original photo, just as in my film (except that the animations I drew weren’t as weird). I wondered what their reaction was when they received the portraits. I hope they were pleased, but I also think they might have been a bit taken aback by the idea that a stranger had spent hours looking at their profile pictures in order to draw portraits of them, without their knowledge. I found this situation quite amusing. It probably influenced the initial idea of the film.

HN: How did you develop the film’s entire story from the initial idea, and what did you take care in the most?

Stephen Vuillemin: Once I had the spark, creating the storyboard happened very quickly. I initially made a first version with a more serious tone, as I was taking this project very seriously! I showed it to Qoso, who did the music of the film (all but the saxophone parts that were created by Jack Willie), and he suggested adding a touch of humor, which was a great idea. So, I incorporated the story of the sandwich and the shoes. The story remained unchanged after that.

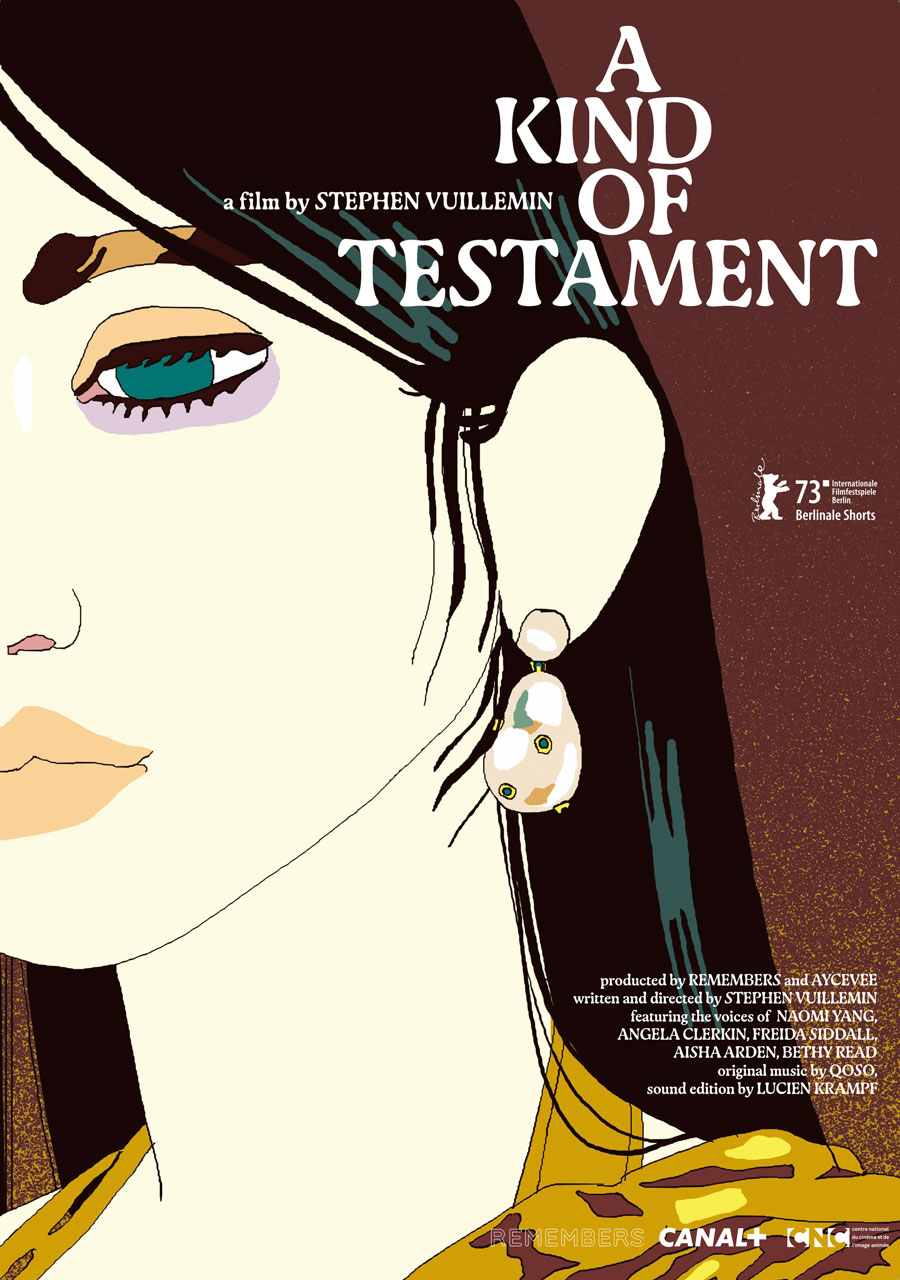

HN: Its surreal visual style with bright colour palettes and electric sounds made it feel like to me a dystopian sci-fi horror film set in our modern age. How did you develop the visual design and the colour palettes, and what were your intentions behind that?

Stephen Vuillemin: Thank you for this insight! The visual style and palettes align with the style I’ve been developing since I graduated from Gobelins in 2008. It results from my working approach (I don’t use colour overlays or blending modes), the hierarchy of my interests (I’m more interested in costumes than in lighting, so I try to showcase the colours in the characters’ clothing without a filter), and a taste for opulence (I aim to coexist with as many different colours as possible within a single image). Since I use a lot of colours, including very bold ones, it’s a lot of fun trying to create harmonies and contrasts in such conditions; it’s more challenging than with more restricted colour palettes.

HN: Could you please let us know the story behind the music of the film?

Stephen Vuillemin: I’ve wanted to work with Qoso from the very beginning. I did a music video for him years ago, and we share a lot of references, so it was easy to collaborate with him. When I was editing the animatic for the film, I used a cello sample from the rap song Still Tippin by Mike Jones wherever I wanted a musical emphasis. It was a kind of nod to Qoso, because I knew he loved that song as much as I did. I asked him to find a way to accentuate what was happening on screen whenever he heard that sample. But my producer Félix de Givry suggested keeping the sample in the final version, which was a brilliant idea. It’s a powerful sample, and it imparts a unique identity to the film – an identity close to mine, as I’ve been listening to Still Tippin regularly for nearly 20 years.

There are also parts with saxophone, when the main character gives birth, and at the end, when we discover her daughter. These parts were created by Jack Wyllie from the instrumental band Portico Quartet, who is also the co-founder of 19 Sound, the studio where we recorded the film’s voices in London with Will Ward. I was thrilled to have him in. I asked him to play his saxophone to match the character’s breathing during childbirth and to improvise during the “release” – and he came up with these beautiful loops.

Regarding sound design, it was coordinated by Lucien Krampf, also a musician, and they worked closely with Qoso to blur the line between sound effects and music.

HN: What creative challenges did you face during your journey to develop this film, and how did you achieve them or conquer those difficulties?

Stephen Vuillemin: Since it was produced in two phases, first by myself and then with Remembers, I encountered two very distinct sets of challenges.

When I was working alone, the main challenge was to stay focused and motivated. However, I enjoyed making this film so much that it was never really an issue for me! I never took vacations; whenever I had time, I was working on the film. Then, when it came to finishing the film within a production framework with Remembers, the primary difficulty was meeting the deadline and working within the budget. Fortunately, I was surrounded by great support! I had an amazing team. This studio is quite special because everyone is incredibly talented and there’s a strong culture of mutual assistance.

HN: I felt that the characteristics of the animation, which allows you to create the characters and the world with more freedom in visual design and style, is a perfect match for the story. What part of animation attracts you the most as a visual storytelling medium?

Stephen Vuillemin: When I began this film, I really liked the idea of having complete control and creating moving images from A to Z. That’s partially why I started by myself – studio work is very fragmented. Delegating means losing a part of that control.

However, after spending six years making this film, I feel like I’ve fulfilled my need for control (for a while), and in the future, I’d like to work more collaboratively so that I can put out more projects within a shorter timeframe.