This is part of an interview series in collaboration with CEE Animation. We would like to introduce award-winning animated short films directed by upcoming young creators from the Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) region and the story behind the creation of each film. We give big thanks to Aneta Ozorek and Marta Jallageas for their great support in this series.

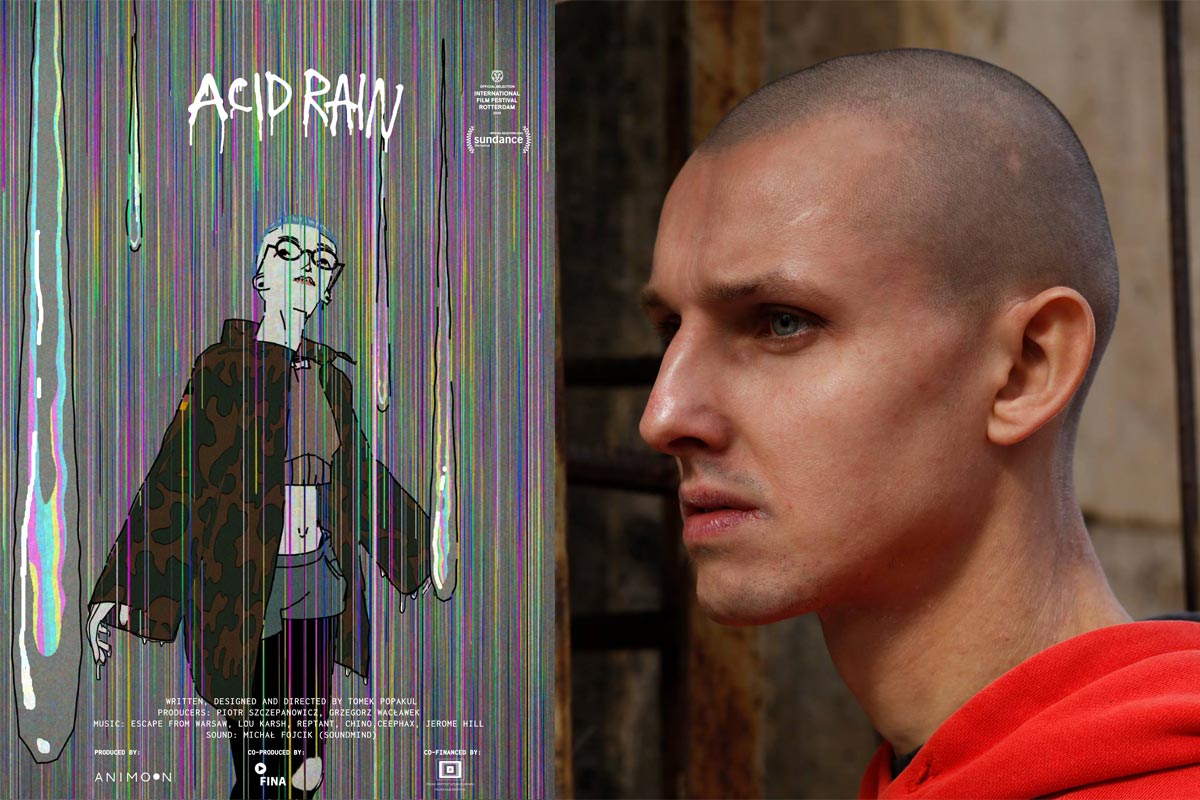

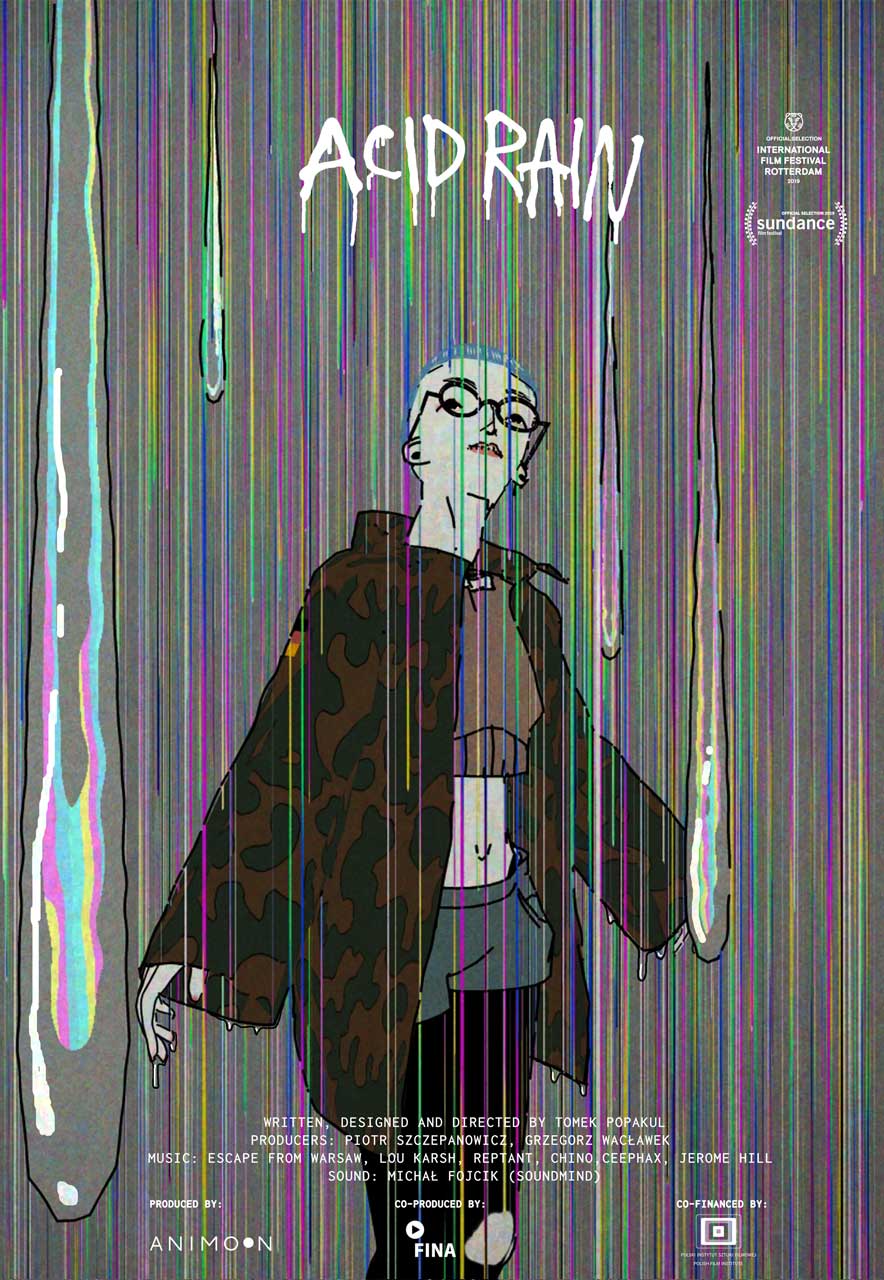

Acid Rain

Synopsis

Somewhere in Eastern Europe, a young woman runs away from her depressing hometown. Her early enthusiasm on the hitchhiking falls when she finds herself in the city outskirts in the middle of the night. At the bridge she meets a figure balancing unsafely on the guardrail. That’s how she meets Skinny – a kind of unstable weirdo. Skinny lives in a camping van, which he uses to run his not-so-legal job errands. Together with him, she sets on a journey with no destination. As the ride continues, a particular affection grows between the two of them.

Film Credits

Direction, Scriptwriting, Visual design, Editing: Tomek Popakul

Producer: Piotr Szczepanowicz, Grzegorz Wacławek (Animoon)

Music: Escape from Warsaw, Lou Karsh, Reptant, Chino, Ceephax and Jerome Hill

Sound: Michał Fojcik

This is a special interview with Tomek Popakul, a multi award-winning Polish animation director, on his latest film Acid Rain (2019). Tomek is a young animation creator with a bright future as a globally leading animation artist. He studied animation at Łódź Film School, a prestigious school in Poland, and has been developing well-received short films, such as the multi-award winning Ziegenort (2013).

Acid Rain is an animated short with edgy visuals and up-tempo electronic dance music, which describes a story of a young woman’s impulsive hitchhike trip with a man, who is a bad influence, and guides you to an eccentric universe of rave culture. The film won many prestigious awards globally, including Vimeo Awards at Sundance Film Festival 2019, Grand Prix at GLAS Animation Festival 2019, Grand Prix and Audience Award at Animafest Zagreb 2019, Best Script at Ottawa International Animation Festival 2019, Grand Prix of International Competition at Stuttgart International Festival of Animated Film 2020, and Grand Prix at 32nd Premiers Plans Film Festival, just to name a few.

Interview with Tomek Popakul

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): How did you arrive at the decision to develop a film that focuses on the rave scene in the 90s? Where did the initial idea of the story come from?

Tomek Popakul: Of course, I’m too young to experience 90s myself fully, but I had very blurry but vivid memories and flashbacks. I wasn’t on crazy rave parties as a kid, but I grew up on Love Parade*1 anthems and The Prodigy*2. In the 90s in post-communist Europe, the rave wave came at the same time with more freedom in general, it was like fresh air and colors and there was a lot of hope and enthusiasm.

At the beginning of this scene, everything was more local and wilder, social interactions were different, and there was no internet. There were no set rules like “what rave is”, there were people DJ-ing on raves from cassettes because vinyl records were not so affordable. Fashion was much more D.I.Y. and every piece of brand clothing from “the West” was much more celebrated, like Adidas worship.

Many people starting this scene were coming from the punk scene, applying this attitude to the current development of technology, like Karol Suka who I interviewed during the research and provided very old-school tracks to the main party scene in this film. I just like old-school rave sounds, and I hope it’s not just nostalgia, I think they are still crazy and fresh. It’s an endless pit to dig and find something new.

Many scenes in the movie are a reconstruction of my later party memories of me and my friends. Some people are messaging me “is this at that party in 2009?” after watching movie, and it appears that people are recognizing certain locations.

*1: Love Parade was a large, annual electronic dance music event in Berlin, Germany (1989 – 2010).

*2: The Prodigy are a British electronic dance music band.

HN: What kind of message or experience are you aiming to deliver to the audience through the film?

Tomek Popakul: Of course, first of all I would say movies shouldn’t be spoiled or explained in such a way in interviews. Also, I’m not sure if it’s possible to pinpoint only one certain message, and this fact I think would make a good movie. But, I wanted to depict mixed feeling on the dancefloor: When it is around 02:00, you feel like brothers and sisters, and towards the morning, people are starting to turn into reptiles. Good and bad experiences are part of the same life experience on a deeper, invisible level of the strange experience called life. It’s about keeping on going despite the hard experiences you had, still believing in people and moving forward with positive vibe.

HN: How did you come up with the two main characters with their characteristics and visuals?

Tomek Popakul: I usually combine together features of real people that I know personally or I know exist as real people. In this way I can gather the most vivid features of certain personalities and at the same time avoid any attempts of depicting a certain someone directly – I have no right to do that, I don’t want to be judgemental and harm anybody. Another persons’ mind is always mysterious, no matter how much you know them, and you can only guess what’s inside. Every human is unique, but some behavioral patterns are repeating, and life paths are shared.

I like to go to parties and observe personalities, the way people dance and what they wear. One of the motivations in making this movie was to have joy in designing fashion. I like subcultures and the imagery connected to them. But rave culture is much more vague and tricky than, for example, punk or hip-hop culture. Ravers are a very compound, wide and inclusive crowd, so the forms of expression are so varied. For example, at a very early stage of development, a guy named Skinny, one of the two main characters, was about to be more like a psytrance*3 hippie guy in dreadlocks, but finally I decided for him to be more of a sharp gabber*4 guy. So, I tried hard to figure out and pinpoint the “90s vibe”. I had fun digging through archival rave photos, and I was also asking my friends for photos from their past. Of course, in the 90s tattoos and ear tunnels were not so common, so it’s a little bit of a “modernized” 90s.

At some point I had big problem in deciding and balancing out who is the main character. Also, I think both represent two sides of me: one is gloomy and embittered, second one is naive and enthusiastic.

I wanted one character to be very “on the beginning” and second one “went through many troubles”. I imagined both characters being very lonely but in a very different way, yet they need each other. I think in life many strong relationships are happening through coincidence and every person you meet on your path is valuable, and many times in weird way.

*3 & *4: They are subgenres of Electronic Dance Music.

HN: Could you please tell us the story behind the development of the visual design of the unique universe and color palette?

Tomek Popakul: Managing and setting the color palette was very difficult and took quite some time. After making two mostly black and white films, I wanted to make a film as colorful as possible. However, it quickly became apparent that using all the colors of the rainbow is creating a huge, unreadable visual mess and is simply ugly. So, I carefully narrowed down the palette.

I was inspired by old and vintage printing techniques – ukiyo-e, risograph print, where the technical limitations in the amount of colors sparks more precision and creativity in artists. The final Acid Rain palette is a combination of two color groups: UV, fluorescent colors of the early rave scene, and the melancholic grayness of post-communist eastern Europe. I created some rigid rules (with some exceptions) like: “there is no red – all what is red is magenta”, “skin color is always snow-white like in Japanese woodcuts”, etc.

One of my main inspirations were also the organic shapes of Russian folk tale illustrator Ivan Bilibin (great depictions of forests) and the crooked expressive anatomy of Egon Schiele. There is a tiny bit of Seiichi Hayashi, although I’m still far from his elegance.

HN: This film uses motion capture. Could we hear about the production procedure of the animation in detail?

Tomek Popakul: That was originally intended to be quick and efficient, but ended up becoming quite a struggle, though we learned a lot. We were very enthusiastic about one Kickstarter-backed home-use motion capture system. As I’m still waiting for such technology to become available for mere mortals, so far it didn’t look like that. It created a lot of bugs and was very hard to find people for cleaning up the capture material later.

Some shots we then recreated in a professional a studio with great staff, which was expensive but worth of it. However we finally decided to leave some bugs and errors of the old capture material thinking: “hm – it actually looks trippy!” And then at festivals it appeared that the audience loved it, viewers come to me and say “Hey, I loved this idea of using broken motion capture! How did you come up with that?” So, it’s important to keep alert and notice the good things happening in the process, and not be so rigidly stuck to perfection. I don’t listen to jazz much, but they say the best things in jazz are the mistakes and I like this attitude.

The most fun day was recording the dance moves for the party scene. My friend and flat mate at the time is a choreographer, and we were sometimes going to parties together and she gathered a bunch of volunteer dancers for this motion capture session. There was a two hour DJ set played live by a DJ in the motion capture studio, and five people were sweating in motion capture suits going crazy. There was more girls than guys, but later when I was browsing output material I was nicely surprised by how unisex most of the movements are.

HN: Could you please let us know the reason or intention behind your decision to use motion capture?

Tomek Popakul: I love to work with actors, and I love the naturalism of movement from motion capture. I would allow actors to improvise and I love how they come up with gestures and expressions that I would never come up with by myself.

HN: Did you face any difficulties in developing the story? If so, how did you deal with and overcome that?

Tomek Popakul: Yes, many difficulties, and there was a lot of struggle with that. Although writing the first version of the script took a long time, and everything seemed to be fixed in place, at quite a late stage of production I realized that something was not working and I changed a third of the (already made!) scenes and threw out 90% of the dialogue. I guess it’s natural that over the years of production you are different person than the one you were at the beginning, and you changed views to many things so the story needed to be updated. I think it’s necessary to perceive the script as a “living creature” and despite that you must have some sort of “compass” to know where you are going, but it is good to leave some “holes” in the story for improvisation and putting unexpected ideas. It’s good to have one (not many!) trusted consultant for brainstorming when you are stuck.

HN: In terms of music, what did you take care in the most in finding the composer for the film? And how was the collaboration with them throughout the project?

Tomek Popakul: The first idea was to hire one musician to compose the whole original soundtrack. I started to talk with the guys I admire and it appeared that they do not work like that at all, they create under inner impulse and spontaneity, and they can’t create any commissioned work.

So, I ended up with a various-artists compilation, but I’m very satisfied with that. They are artists coming from different backgrounds, referring to the “old-school” sound in very various ways: there is the Warsaw rave pioneer Karol Suka (Escape From Warsaw), the legendary DJ and great producer Jerome Hill from the UK, my colleague synth-exploring Chino, and also the youngster Lou Karsh who created new tracks that sound like if they were dug from some old-school acid crate. I feel very honored to have had the opportunity to talk and work with those guys.

HN: If you have any animation creators that were a big influence for you, could you please let us know their name and what of their creations influenced you the most?

Tomek Popakul: They are not direct inspirations, but I have few of them. Gandahar by Rene Laloux had a great impact on me. I have no idea how my mother got the VHS tapes for that, but instead of a cartoon for kids it appeared to be a hard science fantasy for adults. I saw it for first time as a small child, but years after I revised that experience and it appeared to be still a mind-bending spiritual experience that gives me chills.

I also enjoyed the dark graphics of Batman: The Animated Series curated by Bruce Timm, and I loved the “noir” and “art deco” vibe. Discovering the works of David O’Reily was big thing for me, telling stories with 3D in a different way.