Synopsis

A young boy, shipwrecked on a remote island, discovers he is not alone when he encounters a mysterious Japanese man who has been living there since the end of World War II. But as dangerous invaders appear on the horizon, it becomes clear that the two of them must join forces to save their fragile island paradise.

Film credits

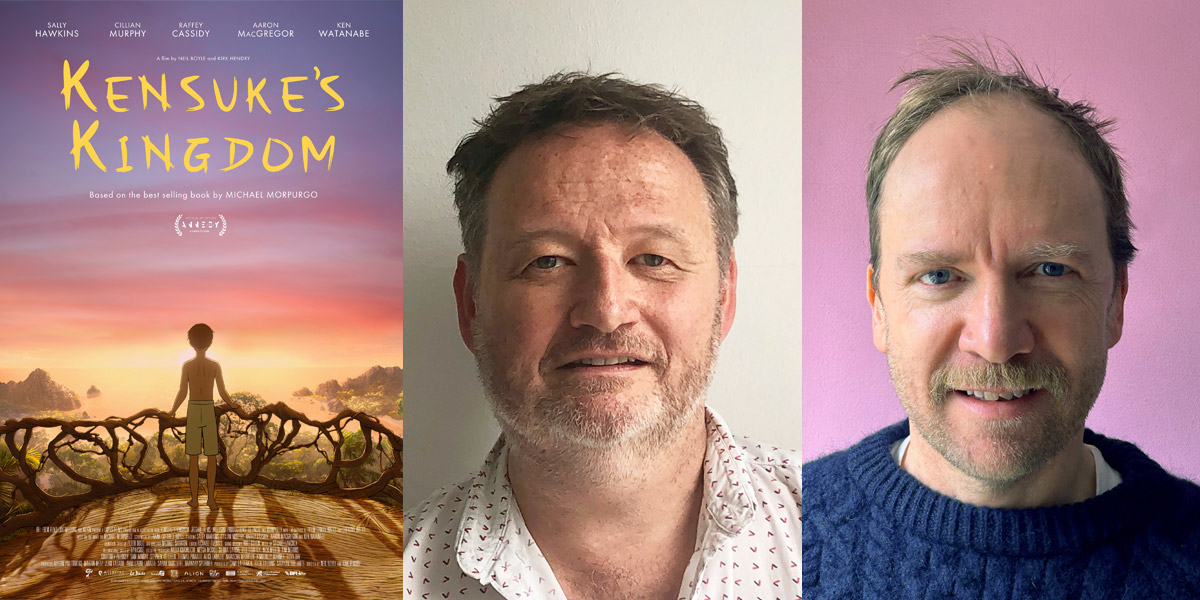

Directors: Neil Boyle and Kirk Hendry

Scriptwriter: Frank Cottrell-Boyce (based on Kensuke’s Kingdom by Michael Morpurgo)

Animation director: Peter Dodd

Art Director: Mike Shorten

Music: Stuart Hancock

Producers: Camilla Deakin, Ruth Fielding, Stephen Roelants, Sarah Radclyffe, Barnaby Spurrier, Adrian Politowski, Martin Metz, Jean Labadie, and Anne-Laure Labadie

Target audience: Teens / Kids / Family

Technique: Drawing on paper / 2D digital

Running time: 84 minutes

Voice cast: Aaron MacGregor as Michael, Ken Watanabe as Kensuke, Cillian Murphy as Michael’s dad, Sally Hawkins as Michael’s Mum, and Raffey Cassidy as Becky, Michael’s older sister.

Kensuke’s Kingdom is a beautiful animation adaptation of a novel of the same name by Michael Morpurgo. The film takes you on a classic, gripping adventure and reminds you of our love for all life on Earth.

We’re sure the film will captivate you in multiple ways and immerse you deeply in its world, allowing you to relive the story whilst sympathising with the characters.

We are pleased to share with you the insightful story behind Kensuke’s Kingdom that we’ve heard from the two directors Neil Boyle and Kirk Hendry. (You can also read our interview on Kensuke’s Kingdom that we did at Cartoon Movie 2017)

Interview with Neil Boyle and Kirk Hendry

Animationweek (AW): What do you think are the key points of the film that you think would attract the audience?

Neil Boyle: We always wanted this to be a very classic adventure story that would attract the whole family. The kind of films that I loved and grew up with, such as Back to the Future and Raiders of the Lost Ark, were the films that attracted a very wide audience, so we worked very hard to try and make it something entertaining for everyone.

AW: We would like to hear the story behind the project. How did you take part in Kensuke’s Kingdom, and what were most memorable things during your whole journey in developing this film?

Kirk Hendry: Sarah Radclyffe, who was the original producer, had optioned the book and was originally making a live action version. But they realised that it was too difficult, especially with having children in the water and live action orangutans. After Sarah had seen some of my works for the World Wildlife Fund, she got in contact and said, “Would you be interested in doing this film?” Neil and I were developing a project of our own at the time and I suggested he should come on board, too. And Sarah agreed.

Neil Boyle: We actually pitched to them our thoughts on the script, essentially how we felt about the film. We did a few little sketches, found some photographic images, and sourced some music from the internet to show that music should be a narrative thing and how it would help shape the tone of the film. Sarah watched it and said, “That’s great, you’re hired!”

Kirk Hendry: It was like a little 15-minute version of the film, but you can just feel the emotion of it. It was a good shorthand way of pitching a feel of something.

Neil Boyle: We’ve always said, “a picture’s worth 1,000 words”, so rather than sitting in a pitch with Sarah and talking for two hours, we just said, “watch this”. It convinced her that we had the right kind of vision for this film.

AW: What part of the original story from the book has attracted you the most?

Neil Boyle: I think it was that element of people learning to communicate that fascinated me the most. I think most of Michael Morpurgo’s stories are in some way about bridging gaps between people of different ages or cultures. Or a very pacifist, anti-war idea of trying to make enemies into friends.

And it’s an interesting problem, how two people become so close without being able to talk the same language. Since Kensuke and Michael initially are terrified and distrustful of each other, and can’t naturally communicate with each other, they find other ways of communicating and over the course of the film, they essentially start to love each other. It was totally fascinating to me.

Kirk Hendry: I read the screenplay first, so that gave me a different impression than the book. I like that the screenplay didn’t have a lot of dialogue. When you read the book, you’re also in Michael’s head the whole time, so you have to find other ways of doing it and Frank Cottrell-Boyce, our scriptwriter, knew this. He made it show rather than tell. So, we have to show the audience what somebody’s feeling and thinking and it draws people in and they’ve become actively involved in it.

Michael Morpurgo is very good at coming up with very slightly strange concepts for books. Like War Horse, a horse’s eye perspective of World War One. And then Kensuke’s Kingdom is a child being washed up on an island and it’s an old Japanese man living there. And then what he cleverly did was making the story so emotionally powerful about people or animals and their interactions that you forget that it had an elaborate premise to begin with. So, the elaborate premises are a hook essentially, and he’s very good at doing that. Kensuke’s Kingdom is a very beautiful example of people who can’t communicate crossing boundaries, because they need each other.

AW: What kind of thing did you take care of the most in the character animation, especially with the communication between Kensuke and Michael, because I felt the delicate and calm movements and facial expressions of them are special to your film.

Neil Boyle: In the film, you have a small English boy who speaks only English and an old Japanese man who only speaks Japanese. You also have all the other animals which the humans can’t speak to. Yet they all have to somehow find a way to live together and communicate.

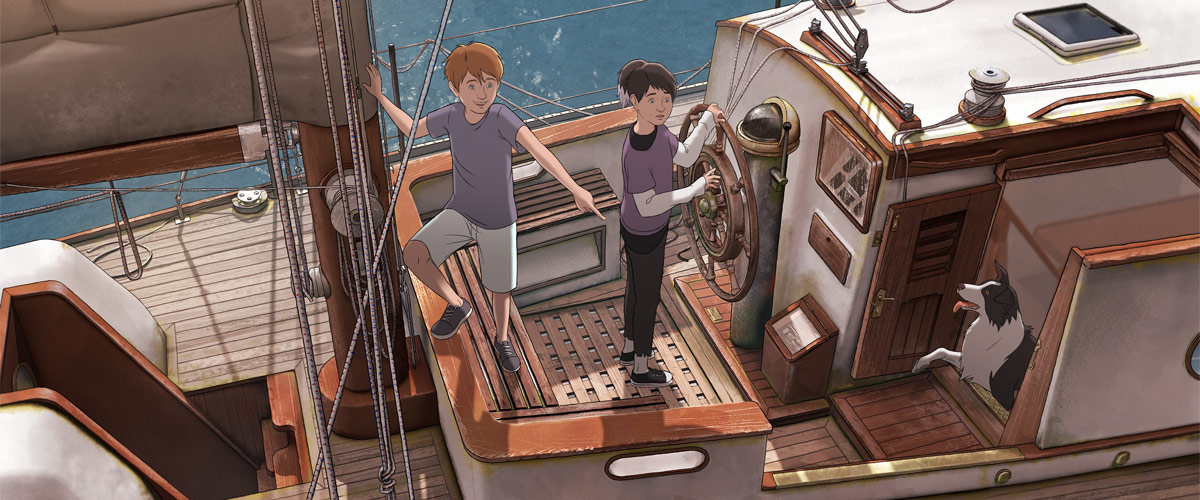

From the start of the film, where you have the characters in the boat, they’re all talking as normal. But once Michael arrives on the beach, we stripped out almost all the dialogue. We tried to find the emotional beats, and we had to figure out how we could communicate exactly those emotional beats to an audience. That was what was so terrific for animation. Because it meant our animators really had to use visual body language to express what was going on.

You’ll probably notice during the film that the landscape reflects Michael’s emotions. If you were on a live action location and you filmed something, you just get whatever the weather was that day. But we specifically would alter the weather, colours or tonal values to reflect psychologically what was going on with the characters. That’s what animation is brilliant at, and often you don’t notice it when you’re a viewer watching it.

Both Kirk and I feel that if you strip things out of the storytelling process, the audience has to work a little bit harder, so rather than just somebody telling you “I feel sad”, they have to watch what the characters are doing. They have to look at their eyes. They have to look at how slowly they’re walking. They have to look at the colour scheme. They’re investing themselves in what’s going on. And we always feel that that brings the audience into the film a little bit more.

Kirk Hendry: Kensuke’s Kingdom has all the excitement of an adventure film, which we were deliberately trying to do, but it is also gentle and slow. I mean it has the fast-paced stuff, but the slow bits are the most effective bits, and those are things that I think we’re most proud of. Richard Overall, our editor, allowed scenes to take their time, making you feel more like you’re there.

AW: How do you communicate with the animators?

Neil Boyle: As a director of animation, what’s interesting is that each animator needs to be talked to in a different way, like all actors need to be talked to in a different way. For example, some animators want very technical directions, some of them want to discuss the emotions of it, and some of them are more insecure about their work and you need to encourage them. Every animator is different. So, you understand your crew to know how to communicate with them.

Before the animation process, Kirk and I went through the whole script and we thumbnailed every single shot in the film, which made up of about 1,200 shots. Then we asked our storyboard artists to draw those up in more detail and begin to think about the performance. So, before getting into animation, we had a quite detailed animatic that began to work emotionally. And then we would talk to the animators about it shot-by-shot to know exactly what each shot was about and what we had to achieve.

The one thing we kept saying is you have to keep this in the realm of naturalism. For example, there’s a sequence where Michael goes to reach for some berries high up on a cliff, and he slips and falls. Now, if he’d fallen like in a Warner Bros. cartoon, he’d have gone flat as a pancake, which you could do in animation. But we told animators that when he falls, you have to feel like he could hurt himself seriously. We always had to be very careful to make sure, without making a live action film, that we were working within the realms of things that were possible and, at least, naturalistic.

AW: Were there any scenes in the film that were especially exciting or fun or to depict by using the power of animation as a visual storytelling medium?

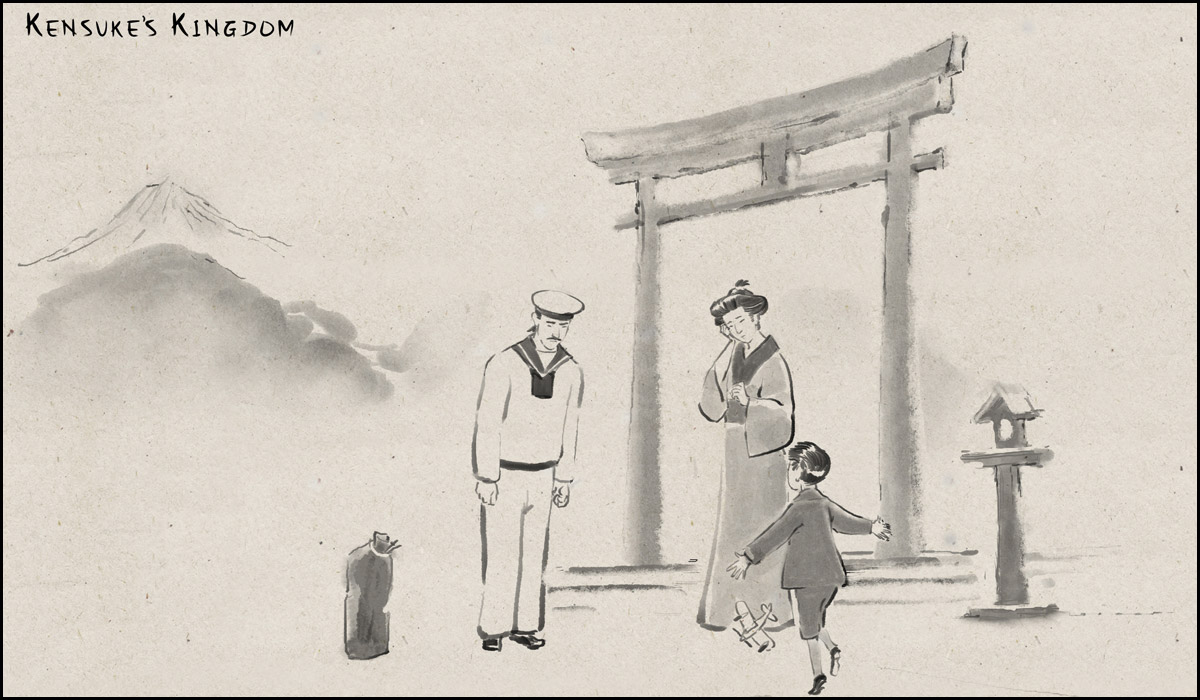

Kirk Hendry: We really loved doing the Nagasaki flashback sequence, particularly because it was a stylistically different thing for the middle of the film. Also, we referenced Hiroshige for that, especially the line quality and the use of negative space. Even with that simplicity, it’s one of the most powerful scenes in the film. And we’re very pleased the way it turned out, particularly with the use of the music. Stuart Hancock, the composer, brought in the idea of using a folk song, and it has worked really well.

Neil Boyle: It just seemed natural to us that if Kensuke is always thinking about his family through his paintings, then that’s how you would see his memories. For us, we think it’s just more interesting and more fun for the audience to take a little breather from the film’s main visual style and go off into another world inside someone’s head for a while.

AW: In scenes where Kensuke, Michael and other animals are in the forest, I notice the shadows of the leaves is falling on the characters. it’s quite unique to have such detailed shadows on the characters. I’m curious about where the idea of that visual expression come from, and what kind of technical challenge did you take?

Neil Boyle: Our fantastic art director Mike Shorten designed the look of the backgrounds for the film. We went initially through the whole animatic by picking stills from anything we could find, such as paintings, and images from other films, that gave us a tonal mood for each sequence. Then we reduced all those images down to be able to see all the 1,200 shots. It created this strange mosaic of colours so we could see that the film was going from something that was very blue to very sunny to a night-time scene, then to an overcast scene.

The reason we did that was partly to get the emotional communication you can get from using colours in a certain way, but also because one of the huge technical challenges of this film is having to condense about 6-7 months of this boy’s life into an 84-minute film that still makes you feel like you’ve been on that island for months. Part of the trick to do that was to take certain sequences, and say “OK, that will be at night; that will be at dawn. That will be afternoon. Then we’ll go to night again”, and so on. So, subconsciously you’re feeling the cycles of nature in the film; the cycles of the days and nights passing, and the seasonal changes. You’re aware that lots of time is passing, such as Michael planting a little seed and then as the scenes go on, it becomes a flower. All of those had to be worked out before we got into animation.

AW: I notice the background art is like a combination of photoreal textures or hand-painted background art and 3DCG animation like the waterfalls. These kinds of different animation technique mix very well. How did you mix these different techniques?

Neil Boyle: Kirk and I are huge fans of multimedia, in the sense of putting different techniques and media together in the same shot. We put them together and then blend and light them so they work in harmony with each other, so it doesn’t feel like a car crash of different techniques.

We have found that if you put two techniques together, subconsciously you will still see the two techniques. But when you put 3 techniques together in a single shot, your brain can’t process it anymore. So, if you light and colour it properly, you begin to accept it as a whole new single image and not different images put together.

It also partly came out of the budget and schedule issues we had, as we had 1,200 shots and many of them in a jungle. All these shots, you’ve got like 45 trees, each with 5,000 leaves. That means we had millions of leaves to paint, which was insane. So, we used a combination of some photographic imagery that we took, which was then painted over.

We didn’t want to have a completely painted background with no pencil outlines, and on top of that have a 2D animated character with an outline trying to sit in front of it. So, we quite often subtly add some pencil line work on the background, just around wherever the character is walking, so that you feel like those two visual elements are going to blend together into one world.

AW: There are several animal characters that are not only lifelike but also we can connect internally with and feel their emotions. I want to hear story behind the creation of the animal characters’ animation.

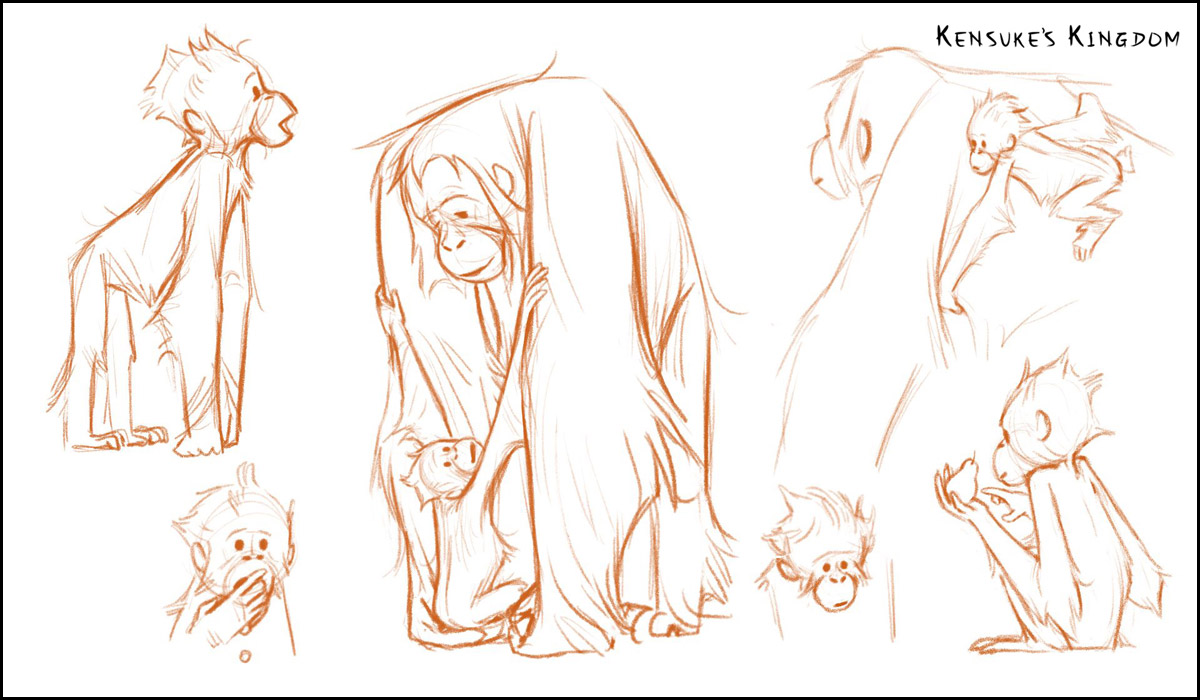

Neil Boyle: One of the animators we must credit massively for that is Ludivine Berthouloux. She is a brilliant, young French animator who we have worked with before. She loves all animals, and she really emotionally connects with them. She understands how they think. She would be very specific about, for example, how a dog’s ears were placed, the angle of the dog’s tail, or anything that expresses emotion that is non-verbal.

Kirk Hendry: She was also one of the main storyboard artists of this film from the very beginning. She’s doing sketches all the time of Stella and the orangutans. And they weren’t even intended to be in the film, but we ended up taking the ideas that she’d had and incorporating them into the film because there was so much character in what she had come up with.

Neil Boyle: For example, she did some drawings when we were trying to find the design of Stella, Michael’s dog, and we both fell in love with her beautiful sketch of Michael with his hands around Stella’s neck, looking into her eyes. Then when we came to storyboard the sequence where Michael lets Stella out of the cabin at the back of the boat, we just went “we need that drawing in the film”. That just came out of creative sketching. Something we then added into the storytelling.

Kirk Hendry: The other key thing that makes you connect with the animals is that we set them all up to have families, so there’s always children, even if it’s just an insect. And if your child is taken away by the poachers, then you will feel that trauma. So, when the poacher’s boot comes in and tramples the bug family, it feels upsetting.

Neil Boyle: And it plays into the theme that Michael Morpurgo is always talking about, where to be respectful of the planet, we humans and animals should all be a little bit more like a family together.

AW: There are a few short shots in the forest scene with certain different creatures. How did you decide which creature appears in each shot?

Kirk Hendry: Whenever we thought to get some animals in there, we’d try to work out what plot purpose can they serve. We always want the idea that whatever Michael did, an animal had done before him, almost like he’s learning off the animals. There are lessons from everywhere, not just Kensuke. Michael is about to repair the glade that has been destroyed by the poachers, so let’s precede that with the spider repairing its web.

Early on, the big lizard eats one of mudskippers on the rock, setting up the daily routine of eating on the island, but Michael can’t eat because there’s no food for him until Kensuke provides him with some. We also always tried to have some sort of subtle narrative idea behind why an animal should be in there. Those animals in that scene weren’t mammalian, warm and friendly. They were reptilian and a bit icky. They were chosen to reflect Michael’s emotional state, and then as he becomes more in-tune with the island, there’s more fluffy animals.

AW: Can you please let us know the story behind the music composition for the film?

Neil Boyle: Kirk and I both worked with Stuart Hancock before on other projects. He is very talented and composes music in a narrative sense. His music can change emotions very quickly, but he still makes it sound like a coherent piece of music. So, we brought him in very early.

In terms of composing music for the film, we always wanted the music to feed into the visuals and the visuals to feed into the music. Right from the animatic process, he started scoring things, even when we hadn’t locked the cut. We’d do a cut, he’d write some music. Sometimes we would re-cut, or cut something out, and he was cool with that or he would adapt his music. Therefore, the visuals and the music were locked together as one coherent thing that was telling the story.

Kirk Hendry: Neil and I like that traditional, romantic scoring from the Golden Age of Hollywood, and we wanted it for Kensuke’s Kingdom because we feel this film is a mixture of two things: a romantic adventure, in the old sense of romantic adventure, but also a very small personal film and a very emotional one. So we wanted someone who could deliver that breadth and subtlety in the score. Whilst atonal or modern music can be very effective, we needed something romantic and harmonious for Michael and Kenseuke’s relationship.

Neil Boyle: On the other hand, we got Stuart to do atonal music in that sequence where Michael wakes up on the island and feels alienated. The last thing we wanted was big, bombastic music, so Stuart did very subtle, atonal stuff that just slightly puts you off-balance and creeps you out a little bit while you’re watching it, so that you can feel Michael’s discomfort.

AW: What did you take care and the most in terms of the selecting process for the voice cast and what were the challenging parts of that?

Neil Boyle: We obviously needed well known names so that the film has the commercial selling point that people know some of those names, at least for the older cast members. But that said, they still have to be the right performers for the characters. For example, Cillian Murphy, who acted Michael’s dad, is a nice guy in real life and he has a very warm side to his voice. We thought that a potential problem with Michael’s dad is that if his voice is a little bit too aggressive, you could really dislike him as he’s telling Michael off a lot. So, you have to cast for someone like Cillian who can pull that warmth off.

The toughest to cast was Aaron MacGregor, who played Michael. We looked at 40 or 50 actors around about the age of 11 and found Aaron. He was just unbelievably good. He actually has a Scottish accent, but he could do an English accent. He’s a very natural, down-to-Earth boy, who has none of the stage school theatricals, but he could take technical direction, listen and concentrate, and do an absolutely fabulous professional job. But as soon as you said cut and go have a break, he was a little kid again. It was a lovely combination.

Kirk Hendry: Producer Sarah Radclyffe, from the very beginning, had the dream to get Ken Watanabe on board. We thought “how likely is that?” And then he read the script, loved it and said yes, we were so thrilled and he was incredible to work with. He was just so professional. Even though a lot of his lines are just grunts, he wanted to work out what every grunt meant. It was amazing to watch him.

Neil Boyle: And Sally Hawkins was totally invested in the role, Michael’s mum. She’s an actor who is very intuitive. So, you talk her through the scene, you show her the animatics so she can understand spatially what’s going on with the characters, and then get right into it and she really felt that stuff. She was screaming for Michael when he goes overboard, and we were saying “Are you okay, Sally? Do you need a break?”. And she goes “No, no, It’s fine. I want to do another one. I’ve got the energy” and she’d be screaming again. She’s brilliant.

And then we had Raffey Cassidy, who played Becky. She needed to be somebody who could be a little bit of a stroppy teenager/older sister, but still be likeable. So, you get that sense of the kind of love/hate relationship that some siblings have between each other. And she was really into it, and terrific as well. So, we had a fantastic cast. We were really lucky and they were lovely to work with.

AW: What were most memorable things for you during this entire journey in creating this film?

Neil Boyle: It took many years to get the money together and we finally got the green light, just as COVID hit. So, we very quickly had to set up a production system that meant everyone could work remotely, and credit to the production staff at Lupus Films who made that work so it didn’t cause Kirk and I any problems at all.

We’ve always said that the making of this film is a little bit like the film itself: because of the COVID lockdown, we were all trapped on our own little desert islands making this film. We always said that maybe making a film about being isolated on a desert island is not such a bad thing and it kind of feeds into the film in a weird way.

We were on screens in our rooms for 10 hours a day, the same as if we had been physically in the room together. So it made very little difference in the end.

Kirk Hendry: I think the most satisfying thing for me is working on the animatic for six months. The pure creativity of the animatic is a magical process of something coming to life that wasn’t there before. It’s where the film is made.Once you’ve locked the animatic, you go into production and then it’s the minutiae of recreating what you’ve already got with better performances.

Neil Boyle: Once you’ve got your animatic, each other process that comes in after is like the icing on the cake: The animators come in and they add a level of performance; Michael Shorten and his team come in with the environment, and you get the sense of the actual island coming to life; Stuart’s got his emotional take on it with the music; and Will Cohen, our sound designer, doing the sound design, populating the jungle with atmosphere.

Kirk Hendry: I think the favourite thing for both of us is when you record the music with an orchestra, and that’s always just a great thrill.

Neil Boyle: There was a little story during the recording. I lost my bag somewhere, so I was looking for it and ended up in the orchestra control room, and they happened to be working on a sad scene towards the end of the film. I’ve heard the music before on synthesisers, but never heard it with a full orchestra. I was looking at the monitors and listening to the music of this very sad scene, and I realised I was crying. And then I looked over at Stuart Hancock, the composer, who was bent over his music sheets, and a teardrop came down from his eye and hit the notes on the sheet. Our editor Richard Overall was behind him and was dabbing his eyes with some tissues. There are three grown men in this control room and we’re in tears watching this scene! That’s the power of when you get an orchestra together and they create this incredible magical moment with their music.