On-Gaku: Our Sound

Synopsis

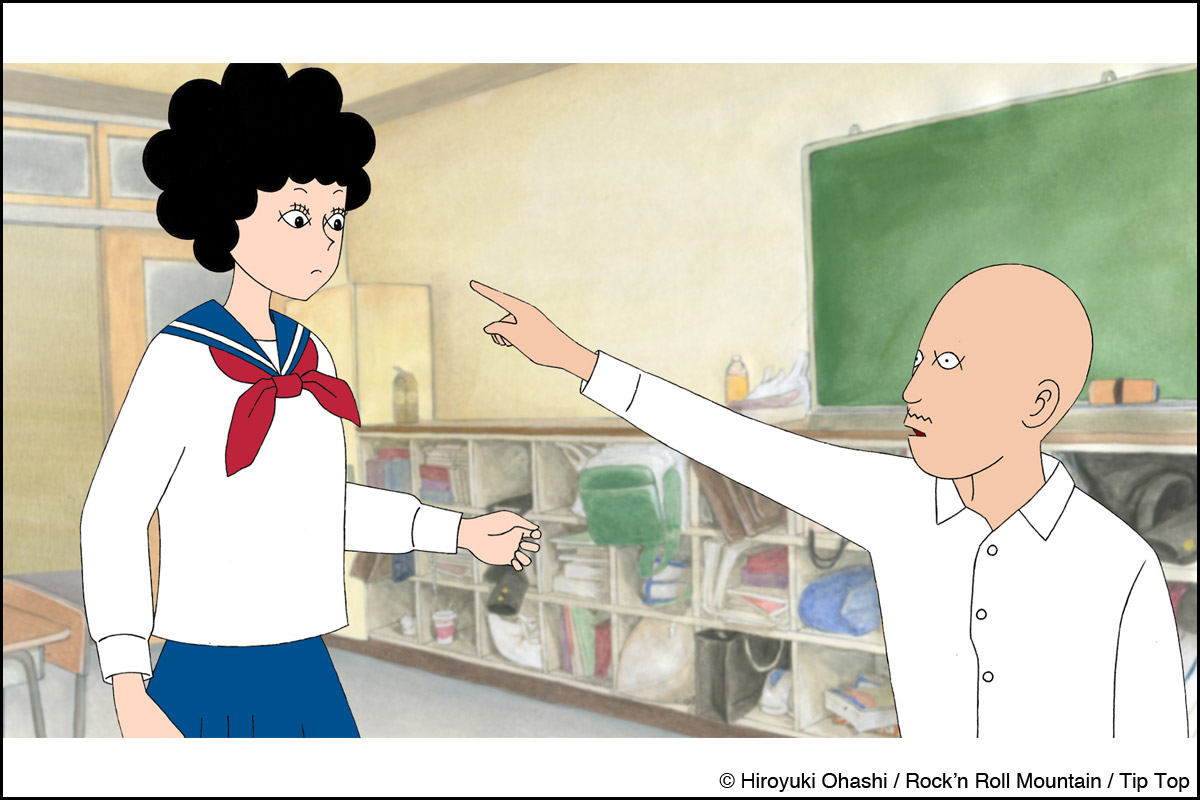

One summer’s day, a group of yobbish high-school kids, who’ve never touched an instrument in their lives, decide to form a band. This is how they start playing a youthful and quirky rhapsody.

Film Credit

Director: Kenji Iwaisawa

Autor: Kenji Iwaisawa (based on manga On-Gaku by Hiroyuki Ohashi)

Music: Tomohiko Banse / Grandfunk / Wataru Sawabe

Sound: Takaaki Yamamoto

On-Gaku: Our Sound is a Japanese indie animated feature film based on Hiroyuki Ohashi’s manga of the same title, which was developed by the director Kenji Iwaisawa for over seven years with rotoscoping animation technique. The film received the grand prize of the Feature Film competition at Ottawa Animation Film Festival in 2019 and was nominated for the best indie feature at the 48th Annie Awards.

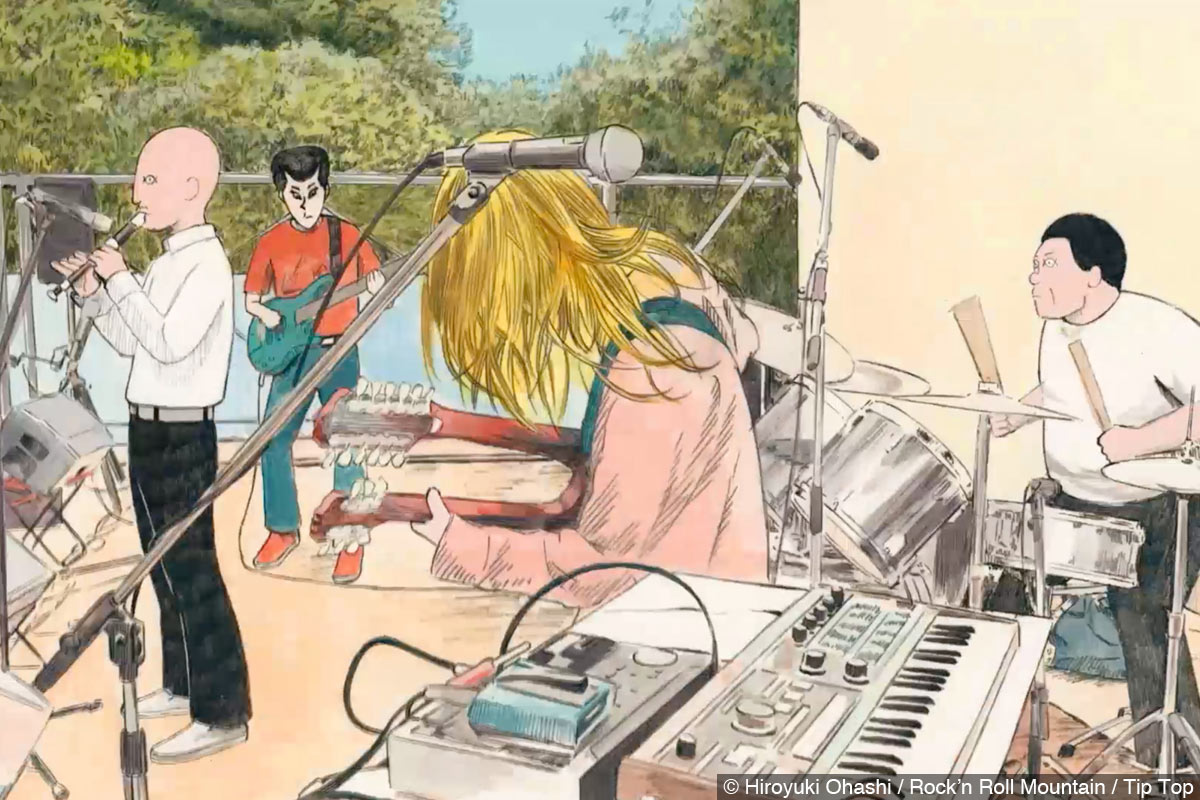

The three barefaced delinquents at a high school form a band and enjoy the sounds of instruments being truthful to their emotions, despite being complete beginners. They sublimate their passion in an unexpected style of energetic music.

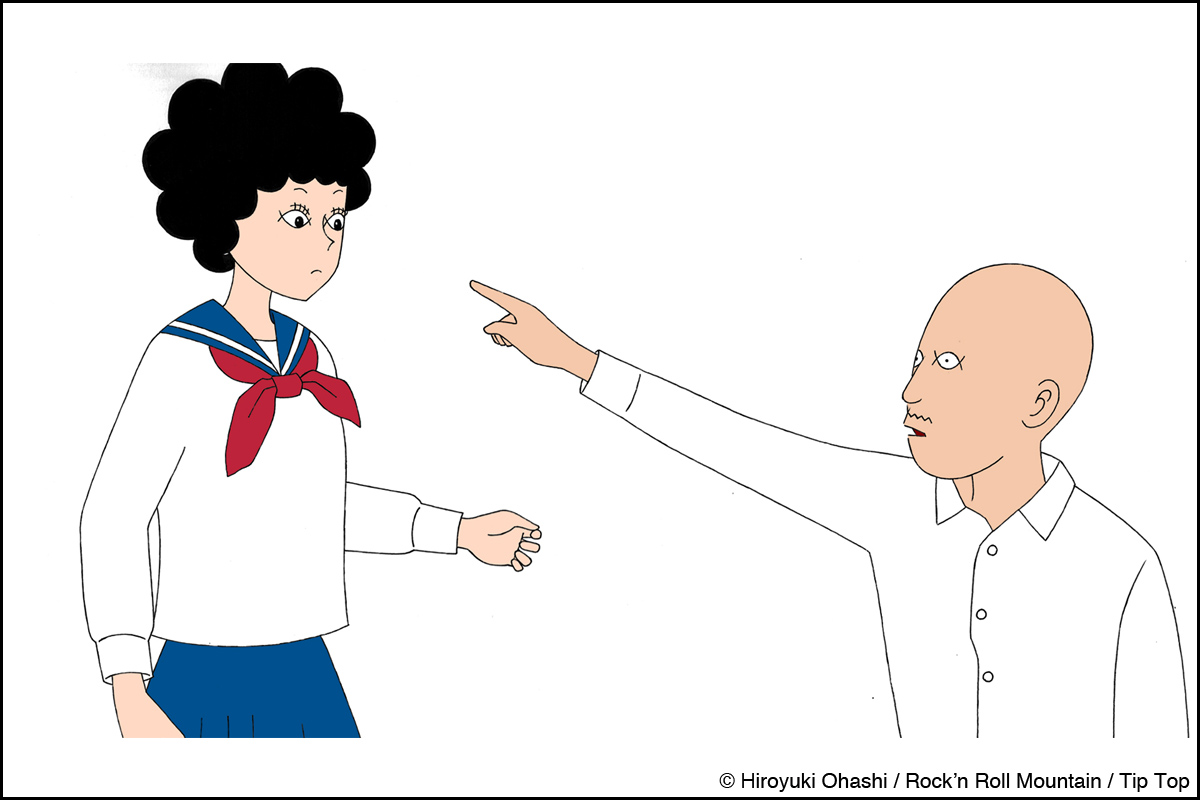

With very unique characters drawn in simple but memorable designs, distinctive pacing of the storytelling, and accentuating the story with artistic expression and comedy, all come together to make an addicting film to watch.

We are delighted to deliver the words from the director Mr. Iwaisawa on the story behind the film, thanks to the help from Kaboom Animation Festival 2021 (From 31st March to 4th April in the Netherlands) for giving us the opportunity to interview him.

Interview with Kenji Iwaisawa

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Could you please let us know the structure and size of the development team of the film?

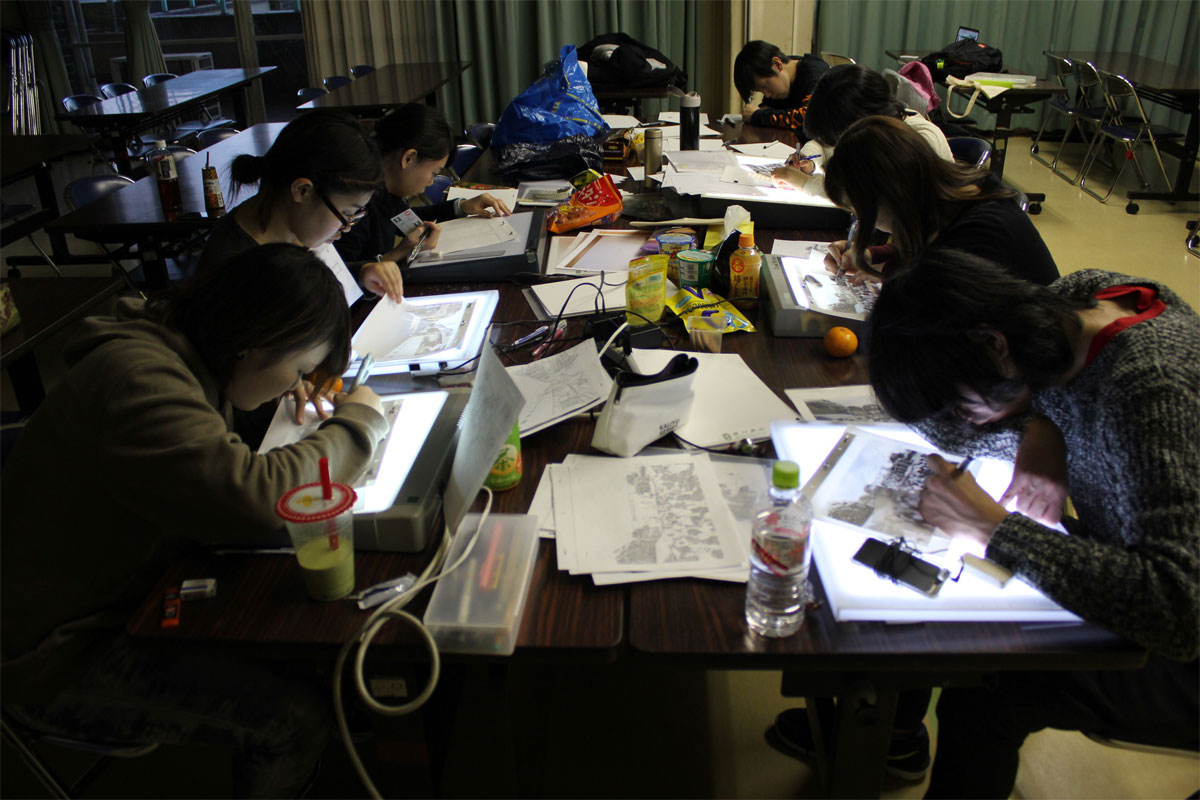

Kenji Iwaisawa: On-Gaku: Our Sound is an independent film, so I started to develop the film alone and then I gradually acquired some staff to help me. In terms of the staff for drawing, the total number was about 30 to 40, but people came and went during the production period. Basically, I managed all the creators of the film project.

There were almost no animation professionals in the staff. The people who helped me were amateurs, so they played more of an assisting role of production. Hence, I needed to do many parts of the production process by myself. It ended up having my name in various roles in the film credits.

HN: This film is based on an original manga. How did that lead to creating the film?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Hiroyuki Ohashi, the author of the original manga, is not one of the super-famous manga artists in Japan, so this film project didn’t start out like, “let’s make a film based on this manga, because it’s a blockbuster and a bestseller.”

First of all, I got to know Mr. Ohashi and we became like friends. Then, I started wanting to make a film based on his manga because his works are interesting. So, I asked him directly about having an animated feature film adaptation of On-Gaku: Our Sound, and thus the production of this film was started.

Actually, the original manga was published privately by Mr. Ohashi. He sold it in bookshops that dealt with self-publishing. It became popular at those shops and caught the attention of a publisher, who began publishing the manga. Also, it went back into print following the release of this film.

HN: What part of the original manga appealed to you and made you want to develop an animated adaptation of the story?

Kenji Iwaisawa: There were several reasons why I decided to make a film based on the story of the original manga.

First of all, the story has humour and includes very appealing characters.

When working on a new film, I am the type of director who prefers to direct a film based on an existing story, rather than creating a new story from scratch. And the original manga is one of the works of Mr. Ohashi, who I personally know very well. Those were also part of the reasons.

In the animated feature film business in Japan, in general there are only projects based on very successful or very popular works so I feel there is no variety. They just think: “There’s a demand for this kind of work, so we made a film of that”. So, in addition to the reasons I gave you, I thought that if I could make a feature-length animation film based on the hidden gem On-Gaku: Our Sound, the film would be able to compete with other Japanese animated films as something completely different from them.

HN: This film has been highly acclaimed not only in Japan but also internationally. What is your personal analysis on what made this film universal?

Kenji Iwaisawa: So far, it was only at the Ottawa Animation Film Festival in 2019 where I could directly see the live reactions to the film from overseas audiences. To me, they seemed to have enjoyed the comedic elements sprinkled throughout the film quite a bit, and were accepting of the emotional beats of the story, such as the excitement of the outdoor music festival scene.

A story of high school students who form a rock band is the kind of theme that has the scent of the bloom of youth and has been depicted in many films. However, this film doesn’t depict the conflicts of the protagonists’ mind. They become shocked at how unbelievably cool the first sound they make on their instruments is. And then, they start to believe and push forward by thinking the sound they make is cool. I think that unfolding that kind of story, which is different from the audience’s expectations and not a pre-established concept, makes this film a universal story.

HN: Does the story of this film have any original parts not found in the manga? If so, could you please let us know your aim and intention on that part?

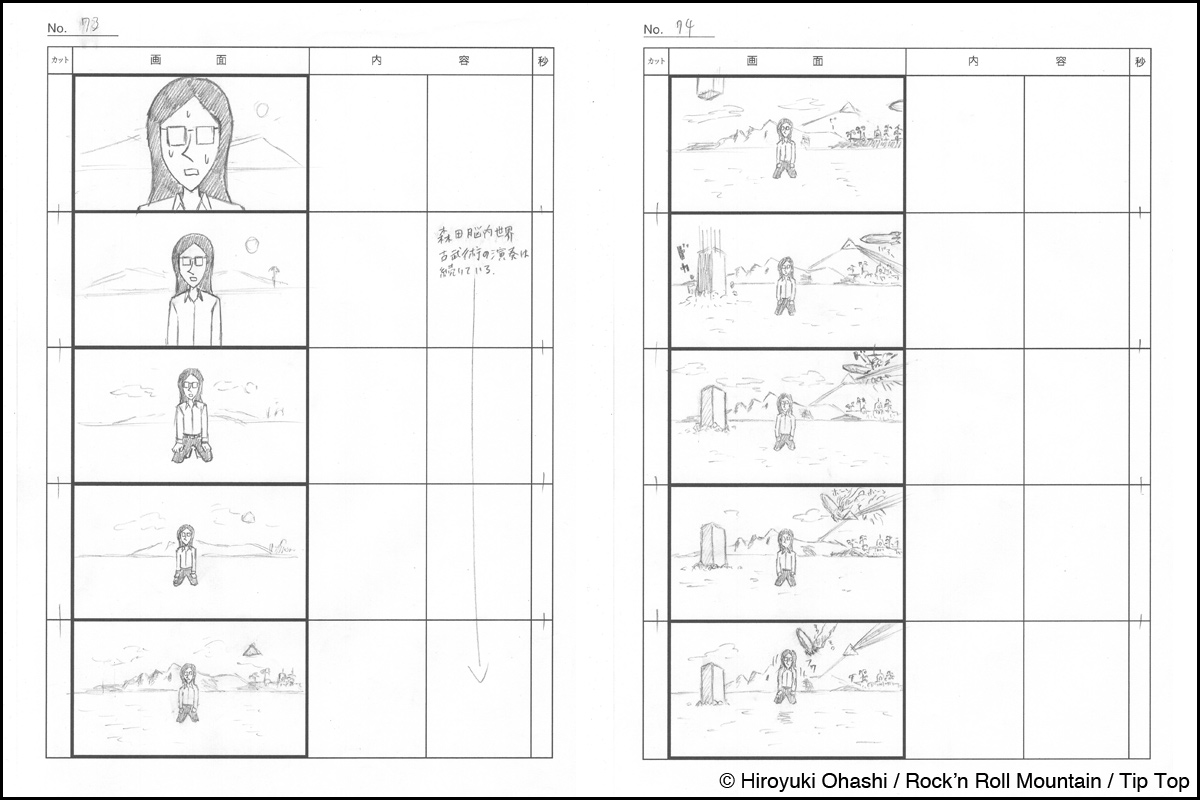

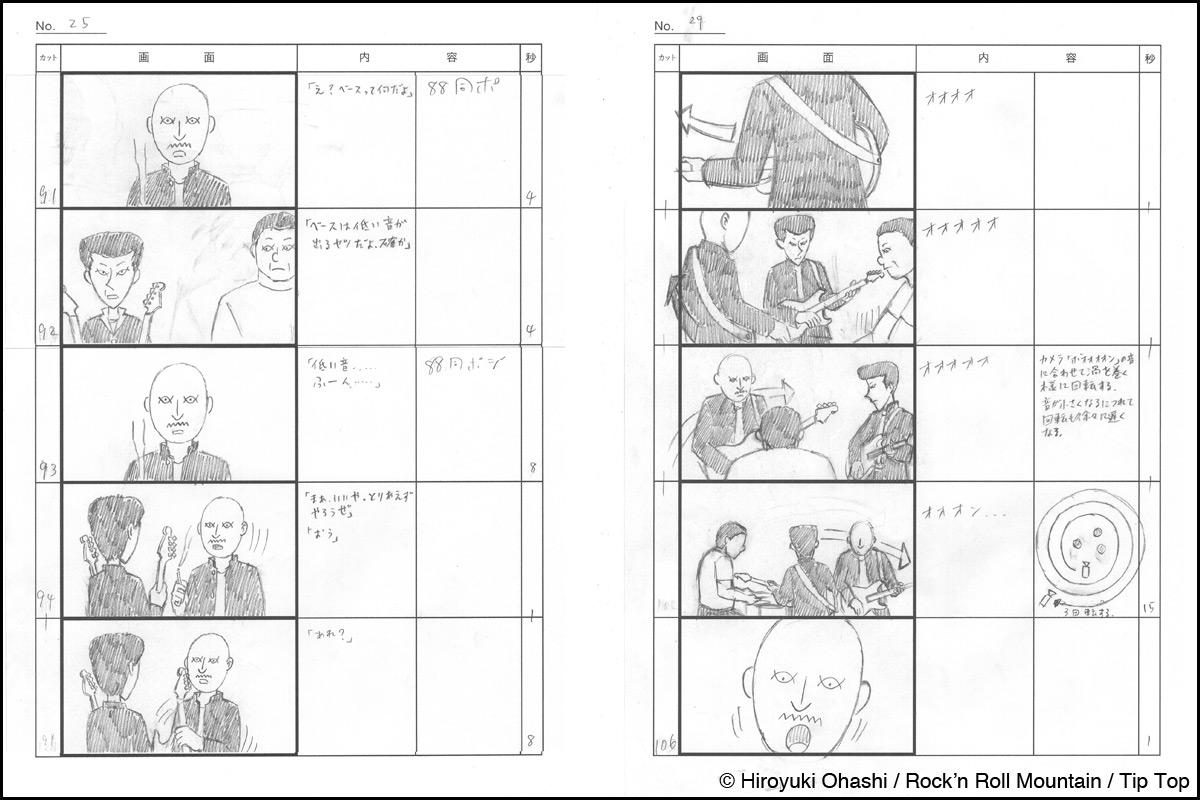

Kenji Iwaisawa: The original manga is a bit of a short story with approximately 100 pages, so if I make a film with only that, it would be no more than about 40 minutes long. So, I’ve added about 30 minutes worth of new, original parts of the story to the film.

Morita is one of the supporting characters in the original manga and not depicted in detail, so I thought I could show Morita more when I developed my original part of the film. Then, I fleshed out Morita’s story in the original manga and treated him almost as a protagonist and increased the number of scenes that highlight him.

HN: What did you take care the most in terms of the whole structure of the film’s story?

Kenji Iwaisawa: I was aware that I was making a film where it relies more on the visuals rather than the story for getting a ‘Wow!’ response from the audience towards the end of the film, unlike with the original manga. So, I’ve decided that the story structure that focuses on the everyday life of the characters in a straightforward manner, and when the main characters play at the outdoor music festival at the end of the film (which is original to the film), the story starts to drive up into a final ‘bang’.

HN: I felt that this film keeps the audience’s interest throughout the first half of the film, even though it depicts the characters’ daily scenes in a monotonous manner. I’m wondering whether it is because of something from the original manga’s story structure, or if it’s anything you’ve devised in visuals.

Kenji Iwaisawa: It was what I directed consciously. Of course, the dialogue between the characters in the original manga is interesting. On the other hand, I intentionally put attractive visuals, which is made possible through animation, at key points in the film.

For example, the scene where the band makes a sound with their instruments for the first time, which I’ve created by making the camera do a full rotation in the scene, is one of the visual expressions in the film that is not found in the original manga.

HN: Could you please let us know the process behind the composition of the music that the band plays in the film?

Kenji Iwaisawa: During the long production period of the film, there were some music that must come before creating the drawings, but others were composed to suit the scenes with completed animation.

For instance, we developed the animation using rotoscoping, and there was some music we needed to have when we shot the live action for that. In terms of the music, I told the titles of songs which are close to my image of music for the film to the composer. It ended up that most of the scores that the musician composed based on my request were exactly what I had in mind, and I gave them the OK on the first go without any modifications. So, regarding to the music composition, I could put good and convincing pieces of music into the film without any difficulties at all.

HN: Was there a turning point for you during the seven-year production period which made you think: “Now, we can finish this film”?

Kenji Iwaisawa: In order to shoot the live-action materials for drawing the final outdoor festival scene, we planned an actual outdoor music festival by ourselves and held it as free-of-charge by setting up the stage and coordinating the musicians. So, the visitors of the festival in the live-action materials were a real, actual audience, not extras like in a normal shooting of a live-action film. We then asked musicians to perform on stage, including parts not used in the film.

The idea of actually organising an outdoor festival for the production of an animation film was not understood by the people around us at all. So, everything needed to be prepared with only two of the staff, me and another, by moving and working about. But in the end, we were able to receive a lot of help and the outdoor music festival came to be. That was when I thought, “Oh, this film project is going to work!”.

HN: Then, the filming of the outdoor music festival to make reference material for rotoscoped animation was not done by asking people to act in a way that reproduced your directing intentions, but instead bringing the atmosphere and the energy of the real outdoor music festival to the film, as if it were a documentary, right?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Yes, that’s right. That was how we could give the festival scenes a sense of presence and a realistic feeling.

HN: Please reflect on your experience of completing a feature film by continuously working on it for over seven years since starting the project as a solo filmmaker. Additionally, if you had any experience that you think will be helpful for creators who are developing or planning to make independent animated films, could you please let us know?

Kenji Iwaisawa: In my case, it really was a simple matter of continuing work on the production without stopping, so there is almost nothing that I can advise them on in terms of the technical side of things.

This is more about mentality, but one thing I know now was that I had a feeling from the beginning of the project that when this film On-Gaku: Our Sound was completed, it would be seen and appreciated by many people. I thought that there were quite many people who wanted to watch this kind of film, as if I was just an audience.

So, I could think to myself that this film would be a success if I could complete it. In the case of a normal feature film, I think the criterion for success of the film is whether the publicity of the finished work could attract a wide audience to theatres. On the other hand, I had the confidence that when completing the film, it will be a hot topic. I think that kind of thing is what makes creators possible to work hard and make it through, even if it’s a hard project.

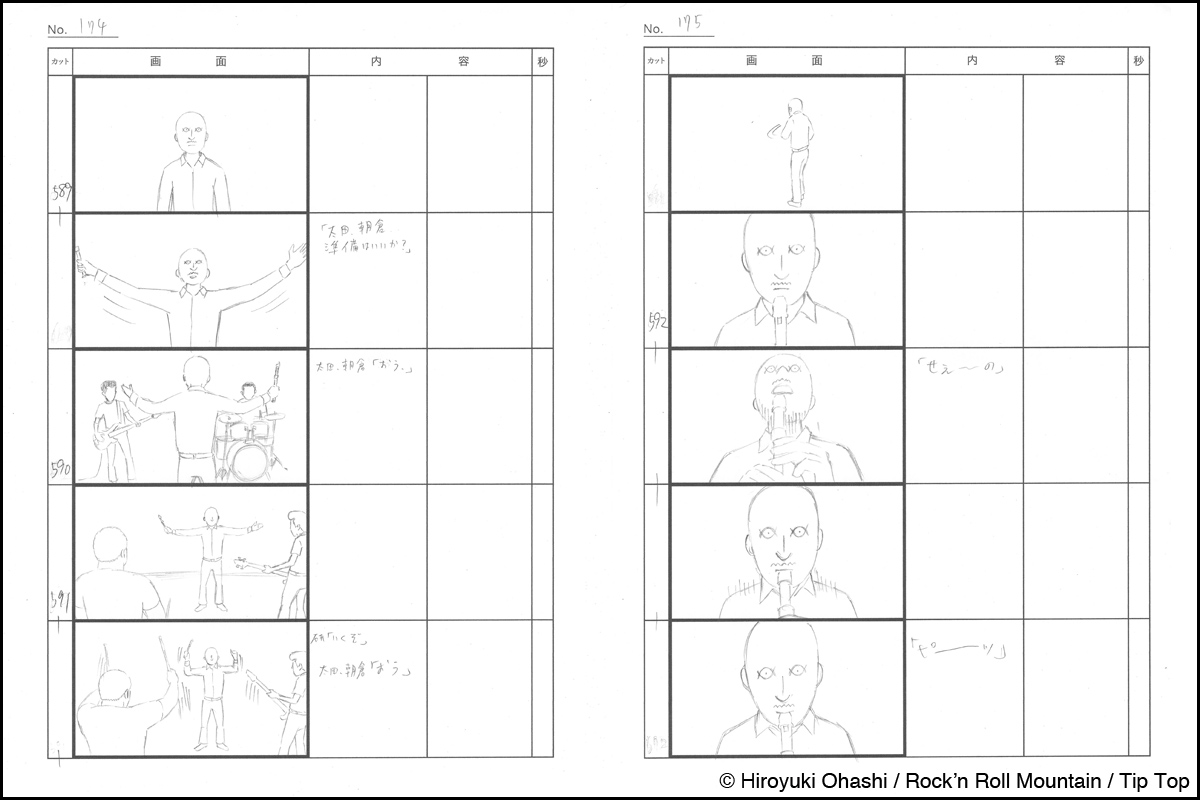

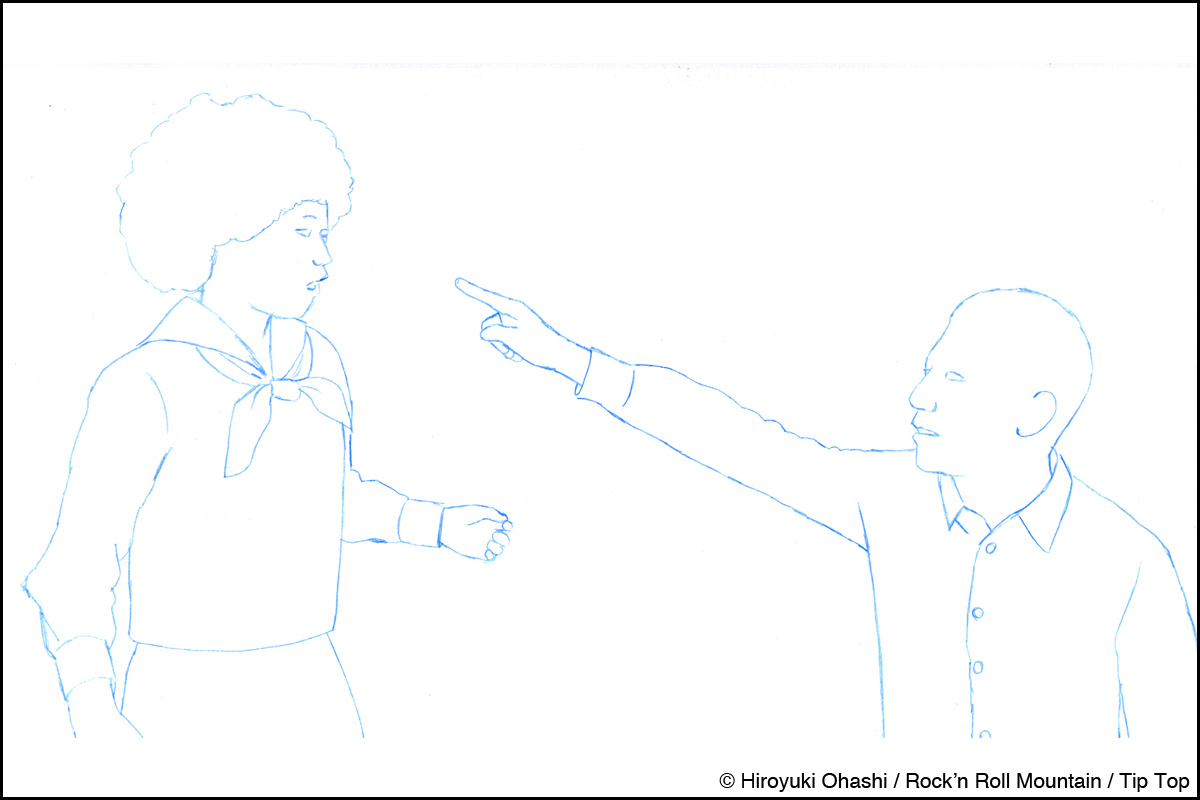

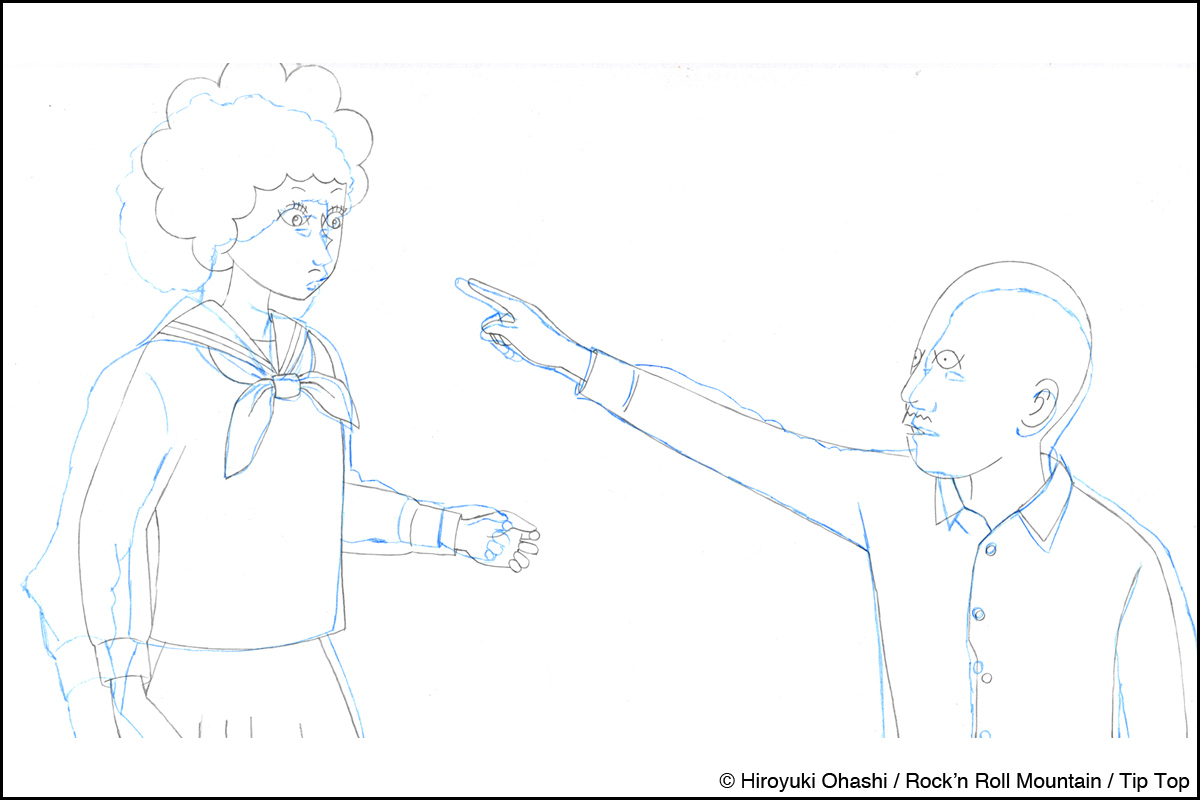

Making a scene using the rotoscoping technique

Kenji Iwaisawa: And one thing what I find strange in terms of film projects in general is that when making a film, people tend to try to immediately establish a framework for the project, such as getting all the necessary staff together first, or getting all the technical things you need for the production. I think many people tend to overly assume that a film project won’t work if all the necessary members don’t come together for the team properly.

Of course, if you can’t form a team properly, I think the film production will often be more difficult. But in reality, a film can be made only by a single director, and it just takes a lot of time.

For example, I feel that most people think rotoscoping, the technique I used for this film, is a difficult animation technique, which takes time and effort. However, for me, the opposite is true. I think the hurdle of making animation is lowered with rotoscoping because live-action videos exist as a base for drawing.

Thinking this way, I think that there are a lot of things which can become a useful choice depending on your way of thinking but you exclude from your option because of your assumptions. I think it’s very important to notice this and manage your project.