FLEE

(Status: in Production)

Synopsis

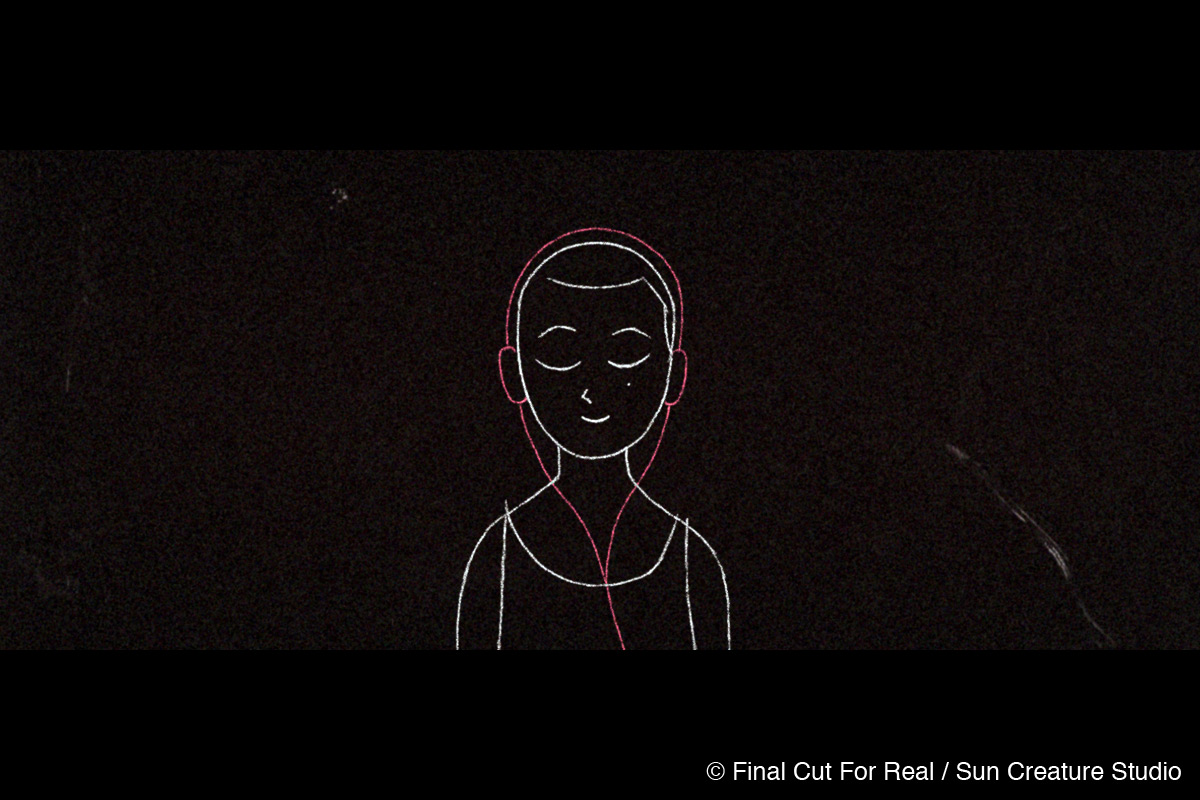

FLEE is an animated documentary that uncovers, for the first time ever, the dramatic background of the life of Amin, who is now 35 years old and lives in Denmark after getting a PhD at Harvard University. The documented footage follows the conversation between Amin and Tobias, which includes five years of an escape journey that started from Afghanistan at the age of 11, and an emerging sexuality in which he came out himself as gay, and is planning to get married to his Danish partner.

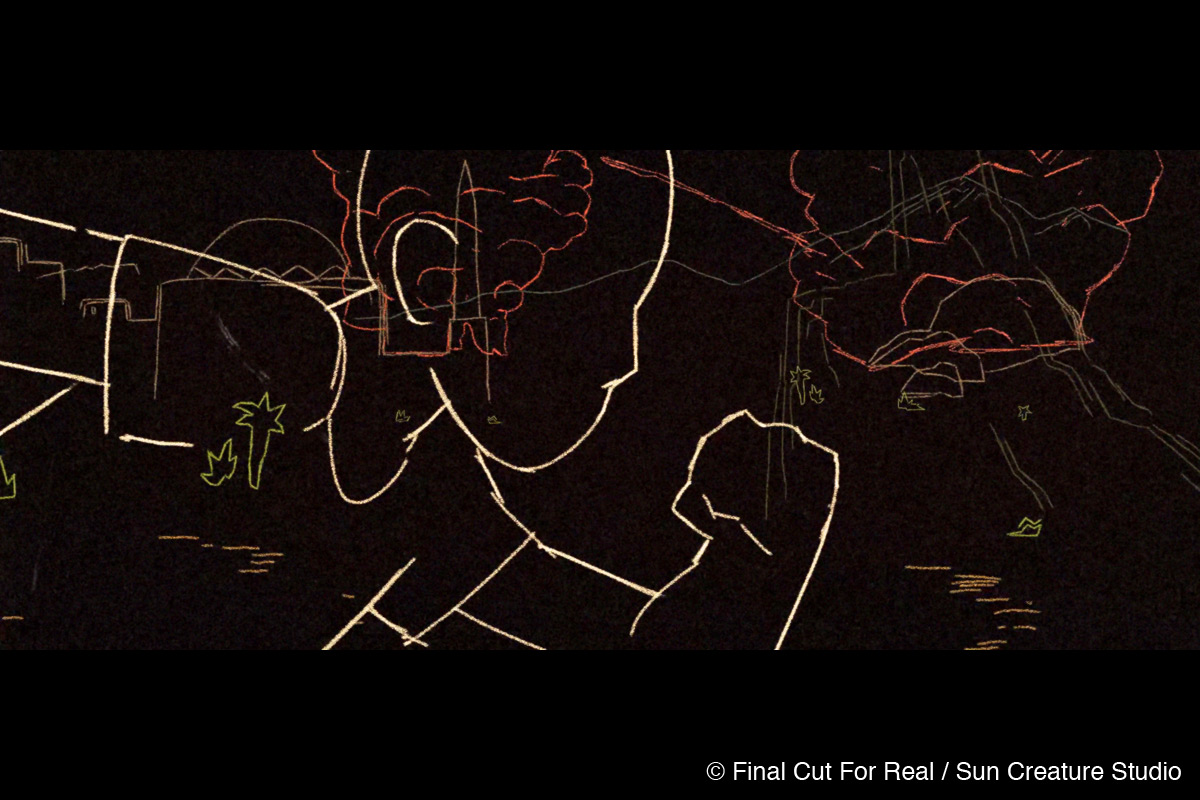

Amin grew up in a privileged environment in Kabul, Afghanistan, but the Mujahedeen changed everything around him. His family attempted to escape to Europe. There were many harsh experiences throughout the escape to Moscow over the Baltic Sea, in a winter storm by a sinking fishing boat. His father was put in prisons in Russia and Estonia as an illegal immigrant. Amin finally arrived to Denmark as a refugee alone in 1997.

FLEE

Director: Jonas Poher Rasmussen

Animation Director: Guillaume Dousse

Producers: Monica Hellström (Final Cut For Real)

Co-Producers: Charlotte De La Gournerie (Sun Creature Studio)

Pitching sessions were held for feature films, short films, TV series, specials, and transmedia during The International Animation Film Market (MIFA) 2016 in Annecy. A team of an animated documentary, titled FLEE, gave a presentation at a pitching session for TV specials on 16th June as one of the selected projects from the originally submitted 400 projects. It also has won the Disney Channel Prize for best new series at the Annecy Festival’s 2016 MIFA market. Now ARTE France is interested in supporting the project with development.

FLEE centres on a story about a boy named Amin who fled from Afghanistan in 1992 when he was at the age of 11, and reached Denmark in 1997 as a refugee by himself after five years of being on the run. Even whilst reaching to his mid-30s, when he tries to get married with his partner to settle down, he still has difficulty in finding peace within himself. He decides to open up and tell the painful experience of his journey in escape to his best friend Tobias, in the hopes of moving on to his next stage in life, and have a place where he can call home. The film is told in the form of a conversation between two friends, Amin and Tobias.

We had the opportunity to interview the director Jonas Poher Rasmussen, the art director Guillaume Dousse, and the co-producer Charlotte De La Gournerie about this animated documentary currently under development.

Meeting at ANIDOX

Animationweek (AW): I think it’s a new and recent trend to create a documentary that utilises the power of animation. How did you start this project? How did you meet?

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: Actually, the idea for the film came up at a workshop called “ANIDOX”, run by the Danish animation school The Animation Workshop. It’s a workshop where they try to combine documentary films with animation. I think they’ve done three of them by now. I was in the first workshop.

I am a documentary filmmaker and I had the idea about this film. I thought, “How do I bring this story from the past to life?” I realised that using animation would be a very good idea. Through the workshop, I met up with Guillaume and Charlotte, and then we started to develop a visual style that matches this documentary story. That was how we got introduced to each other.

A true story based on Amin’s actual experiences

AW: Where did the initial idea of the animation come from, when you decided to make this animation?

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: It very much came from facts. It’s Amin’s story of the past. I know Amin personally and there was a great story of him to be told. I could’ve filmed it as in a normal documentary, such as you would just have him sit down in front of a camera and tell us what happened. But, I would like to make it more vivid and try to make the past come to life. How do you make scenic reproductions of what happened? And how do you make the characters come to life? For that, I thought animation would be a very good solution.

Synergies gained from the fusion of documentary and animation

AW: What benefits are you gaining by using animation to make the documentary after you started to run this project?

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: I think that the synergies gained from the fusion of documentary and animation are one of the benefits. Having a true story influences the animation in a positive way, like you can feel that the story is important to the protagonist because it is voiced by the same person. The images become very emotional and you can become immersed within it. On the other hand, the animation enables the documentable stories of the past come to life. So I think it works well in both ways.

Guillaume Dousse: Yes, animation allows the showing of pure emotion, and it can be very abstract or surrealistic. It’s the first time Amin tells the story, so there is a lot of emotion in his voice, and also he is recollecting memories not in the right order, such as when it happened, and how it happened. Animation can create bridges between ideas and gives chronology that he had forgotten. Animation can also play with the melody. It shows something that is difficult to express otherwise I think. It gives some distance to the character, which makes the story more universal.

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: Amin experienced all this while he’s a kid so a lot of these are experiences through the eyes of a child. You can show that using animation, it’s kind of more childlike view on it, rather than just using real-life footage. This is also the first time he tells the story, so it’s a very personal testimony. It’s a very personal room you are invited into. He tells his best friend the story of his biggest trauma in his life for the first time.

Creating emotion with animation

AW: I’m interested in learning how you visualised emotions.

Charlotte De La Gournerie: We came from 2D animation, so that we relay the story to a more stylised lined animation. Visually, we are now getting into his memories. You can see that the style of the animation changed at one point in the trailer you saw. I think that’s one way of showing emotion by using animation.

Guillaume Dousse: It’s very different from actual live action, whereas you can capture emotion on film, we need to create it from scratch with animation. The challenge for us and where we have to be careful is not to overdo it because of the nature of animation. It’s a lot of balancing between silence and steady shots and music. It’s more about rhythm I think, because Jonas created the first edit with sounds. That’s his vision and way of telling the story. From that, we slowly build an animatic with visual references and colours, and then we’re slowly going to storyboard it and edit it to give the right pace and build of the emotions.

Charlotte De La Gournerie: I think the emotion is carried through in the voice because they are real voices from a real interview, and we put the animation on top. I think that you will be able to feel the emotion in the voice and that is lifted up with the animation as a visual footer under it.

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: This is more like the interview. The story is what he talks about. First we made a narrative just based on the interview, and then we created an animation to show the emotions that are in his voice and in the story. So it’s pretty simple gestures and emotions in his face, created by Guillaume’s team, for the sound of his voice telling the story.

Development of visuals

AW: I think animation has the freedom to utilise the visual style you take. How did you decide on this visual style in particular?

Guillaume Dousse: When we started to work together one year ago, the first visuals we were doing back then were black and white, and I thought it was dry and very harsh, and the animation was a smaller part of the film. But I think the idea of bringing more colours and light to the story helps to make a good composition to show the character well. It can make the film bright and give good contrasts to what Amin says. Then, animation became more important to the film, and now it’s a fully animated film.

Charlotte De La Gournerie: Yes, it’s going to be mostly animation, but then you have the archive footage just as a constant reminder that it’s a real story. We edited some actual footage of Afghanistan, Moscow and Denmark to give depth to the story. Everything in the film was rebuilt, so that you might forget that it’s based on true story whilst watching the animated scenes. So it’s important to put the live footage in it to make the audience realise that it’s a true story.

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: The voice you hear throughout the film is also genuine. So you can have feeling of continuity. When you go to a new place in the film, you see the live footage and the time and place of where you’re at is set. So you can know you’re in Afghanistan in the ’80s, in Moscow in the ’90s, or you’re in Copenhagen in the ’90s.

Guillaume Dousse: It’s not a sad story about someone who didn’t succeed. He went through a lot of tough moments, but he’s very well integrated now. So he has a successful story. For me, what’s important in this project is that Jonas’ intimacy with Amin as the best friend, and that Jonas’ friend tells his story for the first time. I am personally privileged to be a part of the process to hear something as a kind-of friend. So I could have a visual that shows that cosiness, or the feeling that it’s not a dry scene. It’s not the story, just a vision.

I also tried to put my feelings to the visuals. It’s a story of a child that goes through a lot of events and has same questions as any teenager would say. So, as a man, even though I’ve grown differently but I still can refer to some of similar questions I went through in my childhood. Obviously, Jonas is bringing Amin’s story really accurately and the depth of the story. So there’s a good balance between writing the content and visualizing to express it.

Charlotte De La Gournerie: We have a normal phase of concepting, the type of design, environment design for the trailer as animation. We treat those phases exactly the same way we have done to make animation. We set up discussions with Jonas like, “Do you like that? Maybe make it bigger, smaller?” It’s a regular conversation with all of the directors.

Challenge of distribution

AW: For Sun Creature studio, what differences have you experienced through the making of a documentary animation from other projects?

Charlotte De La Gournerie: It’s a co-production with a documentary company called Final Cut For Real. They’re also based in Denmark and we are now working with them. Jonas came with his story but also with the other producers. The world of documentaries has met the world of animation at ANIDOX. We both brought knowledge, skills and networking, and tried to make one movie that has both documentary and animation. I think for Sun Creature, what’s important for us was, we like to tell a story that meets us and looks beautiful at the same time. I think a good story and a good team are very important, and they are there for this project.

This is a challenging project because animation for adults in Europe is an upcoming genre and it’s not the majority yet. It’s very interesting for us to see how we can use the animation to tell stories to an older audience. I think that maybe making it as an animation documentary can attract more people to watch this than as a live action film. I mean this project is not for kids but I think people who are over 15 years-old and are interested in watching animation can watch it as well. So by making a documentary with animation, we might bring people that may not watch it usually.

Guillaume Dousse: As Charlotte says, it combines the two audiences. Hopefully it will make the audience discover more documentaries and get to know more about the context of the story.

Jonas Poher Rasmussen: Normally, these kind of documentaries can tend to be a little dry so they’ll be shown late at night at some small TV channel, but by making it animation, it will hopefully be more appealing to people and will have a better start at television and will have a broader audience.