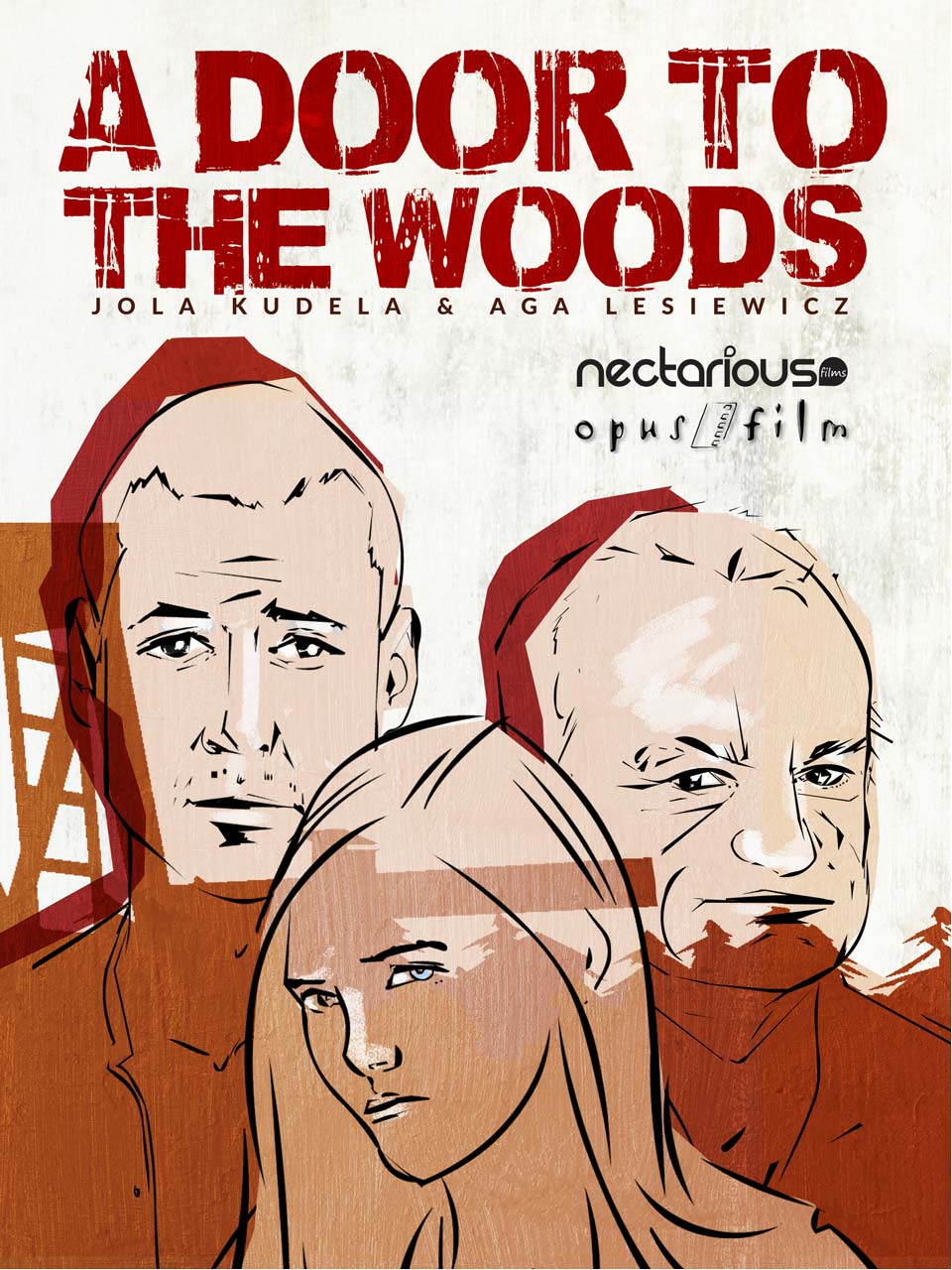

A Door to the Woods

(Status: In Concept)

Synopsis

“A door to the woods” is a Polish idiom, describing something absurd, something that has no reason to exist. And yet it’s those stubborn, sometimes irrational, convictions that help us overcome seemingly unsurmountable adversity and come out the other side, stronger, wiser and, most importantly, alive.

Two young men and a girl, whose lives are intertwined, are forced to fight for survival, each in their own unique way, against three oppressive regimes: Fascism, Stalinism, and Communism.

They can only win by finding their own “door to the woods” and by holding on to human values – hope, love and loyalty – as well as to their artistic creativity.

A Door to the Woods

Director: Jola Kudela

Authors: Aga Lesiewicz and Jola Kudela

Producer: Christine Ponzevera (Nectarious Films, France)

Co-Producer: Piotr Dzieciol (Opus Film, Poland)

Target Audience: Young adults / adults

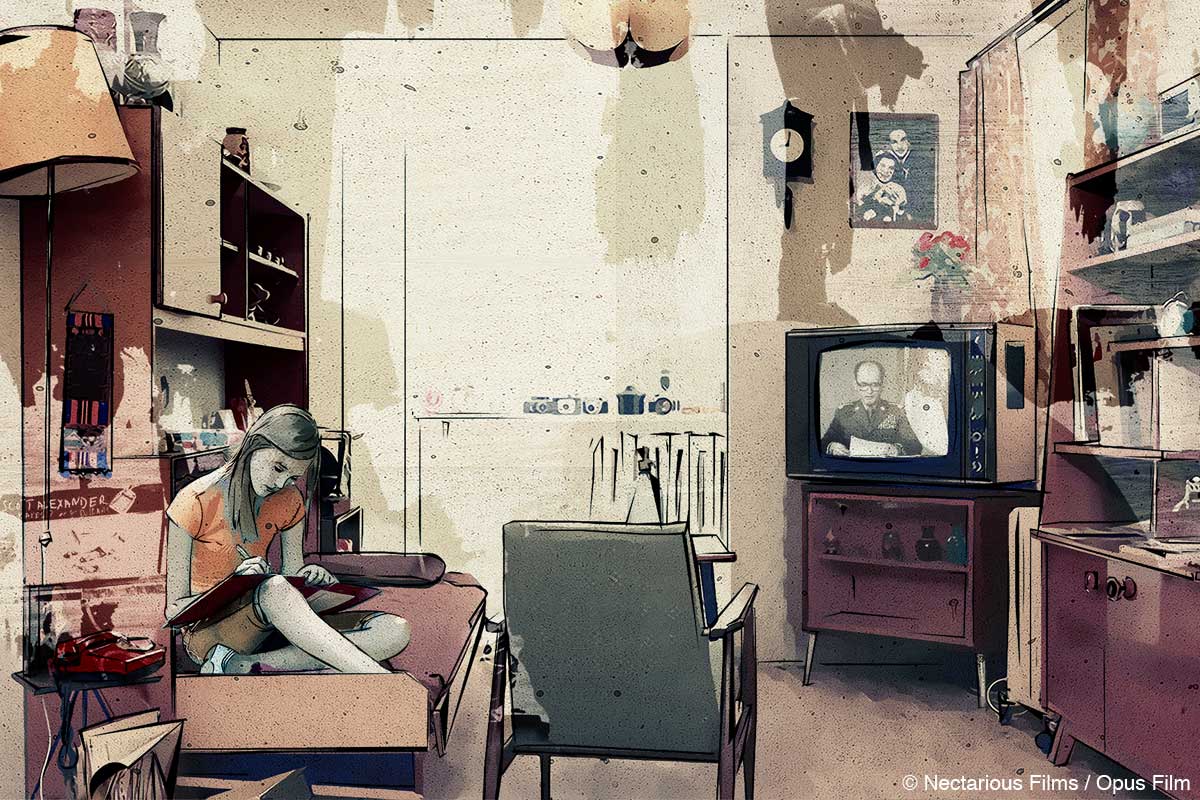

Technique: 2D digital, 3D digital, Live action (Rotoscoping)

A Door to the Woods is an animated feature film project inspired by real people and true historical events, which was pitched at Cartoon Movie 2021. A story of three Poles, whose lives are interconnected, will deliver to the audience an opportunity to remember and learn human history from the oppressive three regimes in Europe during the 20th century: Stalinism, Fascism and Communism. Aga Lesiewicz, the writer, said at their pitch that it is a breakthrough story that ends on a positive note.

We had an email interview with Jola Kudela, the director, and Aga Lesiewicz, the author, to introduce this passionate project.

Interview with Jola Kudela and Aga Lesiewicz

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Could you let us know the key points of your animated feature film project that you would like to appeal to the prospective audience?

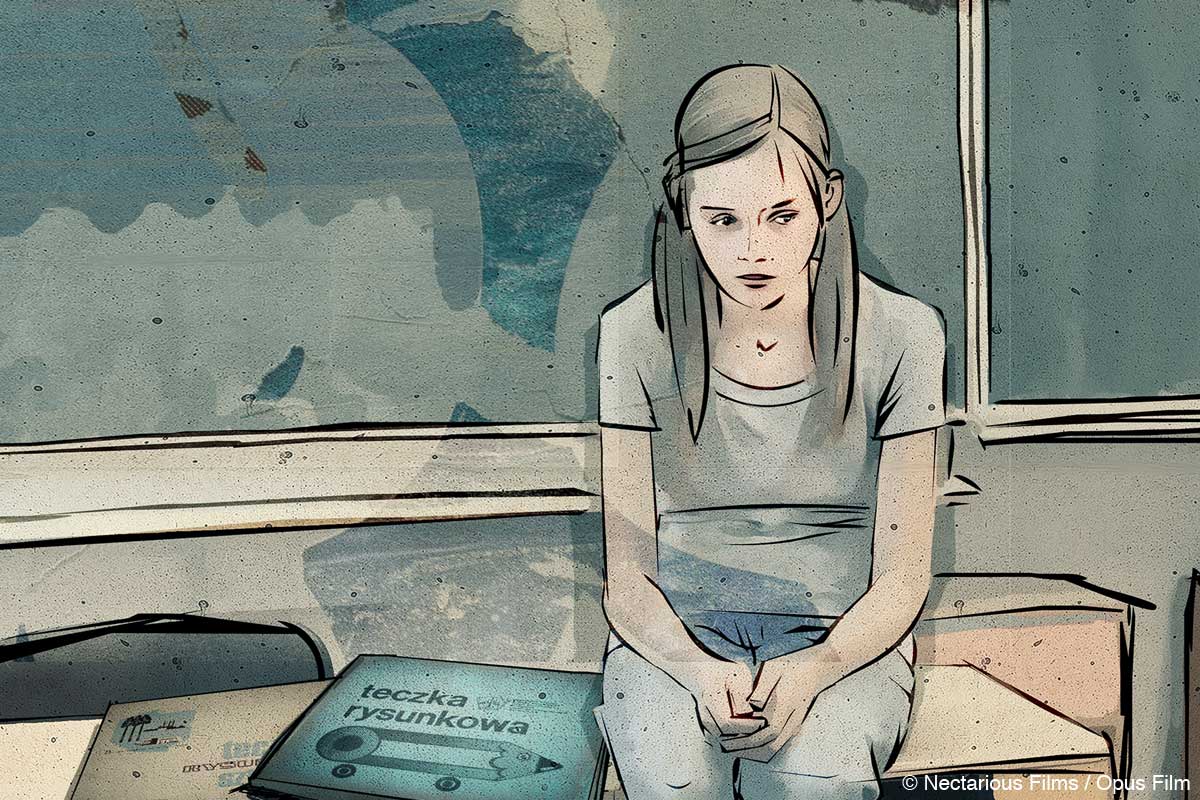

Jola Kudela: The beginning of the 21st century seems like a comfortable place to live in but, increasingly, we can see parallels with what was going on in the world in the 1930s. This film is supposed to be a reminder as well as a cautionary tale about what our future may look like. It’s a breakthrough story that has a happy ending, only because our main characters were smart enough, and lucky, not to be sucked in and trampled by the events they were part of. But they are ordinary people, not superheroes: they’re young, naive, and endearing.

The animation style of the film is meant to make the story more accessible and familiar to the younger viewers, who wouldn’t necessarily seek it out in dry, historical accounts of the era. It’s also meant to be a word of warning: try to learn from the mistakes of your predecessors and act before the world you live in gets changed into a new nightmare.

HN: How did the project start? And where did the initial idea of the story come from?

Jola Kudela: For me it started when I met Aga, who is a writer and promo producer. I have spent most of my adult life in Paris and Aga spent most of hers in London, but thanks to this encounter I have discovered how strong and deep our common roots are and how important is the shared experience of growing up in the same country. As we started talking it turned out that Aga was a writer and was working on a story written originally by her dad, based on his own experience in a Soviet gulag. Exactly at that moment I was looking for a story that I could adapt to a short animated film. I was moved by the story and the fact that it was not fiction, but a strong testimony of the times it was set in. Once it was completed, I asked Christine Ponzevera to come on board. Christine convinced me that the material was strong enough to develop it into a longer form. We had an idea to mix it with my own story and some stories of my family. By doing that I thought we could achieve a more universal and symbolic testimony of the era.

Aga Lesiewicz: I’m a collector of stories. I’ve been carrying my dad’s story with me for many years, not quite sure what I could do with it. It seemed very personal, and yet somehow detached from the man I knew as my father. It was only when I met Jola, who told me the stories of her family, and her grandparents in particular, that it suddenly clicked into place. I saw it as part of a larger whole, it became more universal and relatable. And then I realised that the stories of my dad and Jola’s grandparents, although not geographically connected, were in fact linked through their common experience. Jola’s personal story of a young girl who, against all odds, becomes a filmmaker, tied all those seemingly separate elements together and became a nexus for the narrative.

HN: In your pitch at Cartoon Movie, you mentioned that you plan to use modern art and music for the film. Could you please our readers hear about the arts you have in mind and how those pieces of art affect the film?

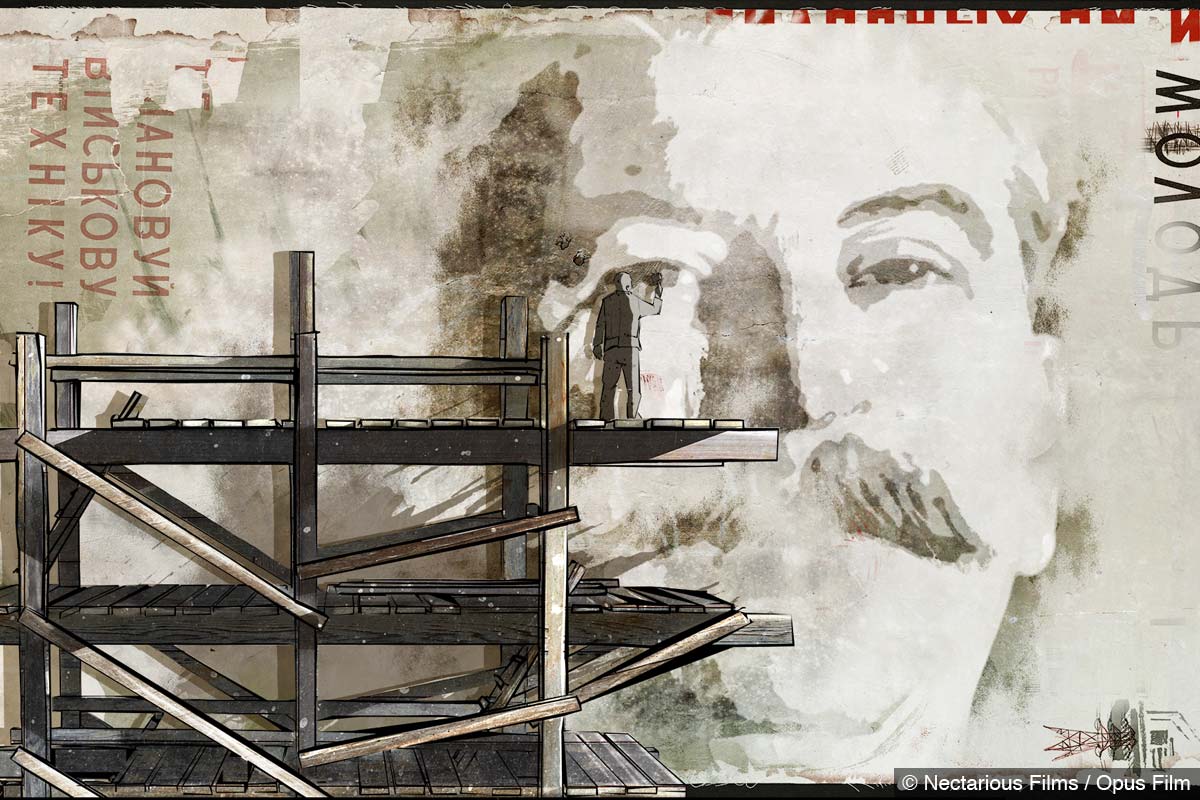

Jola Kudela: The visual aspect of this film are inspired by the aesthetics of the Russian avant-garde posters from the 1920s and 1930s. I’m especially interested in this era because it was a very short period of artistic freedom in the Soviet Union as well as Poland. After 1930, artists faced increasing pressure to conform to governmental standards of acceptable art. In Poland the censorship continued till 1990. And now we seem to be going back to those oppressive times.

Russians graphic designers of the 1920/30s experimented with innovative techniques inspired by the films they were advertising, such as extreme close-ups, unusual angles and dramatic proportions. They combined different elements by adding photography to lithograph, using human faces with distorted body shapes, they also turned film credits into an integral part of the design. The most famous Soviet poster artists were the Stenberg brothers. I particularly like the way they introduced motion to static compositions and contrasts in proportions mixed with the limitations of lithography, as in the poster of the film The Punch (1926). The use of typography in a narrative way is very interesting as well, as in the poster (by Grigorii Borisov and Pyotr Zhukov) of The Living Corpse (1929), where they created a pattern formed by repetition of the title to fill the whole screen, including the protagonist.

Typography is also widely used in graffiti. In occupied Poland during WW2 typography and writing (the signs with a big “P” in an anchor, or hanged swastikas) were used to give people hope. By the end of the Communist era this form of protest came back in the works of Włodzimierz Fruczek, with his outlined humanoid shapes, or Waldemar Fydrych’s “Major” from the happening group “The Orange Alternative”, who was famous for his funny painted dwarves carrying anti-government messages on urban walls.

So that’s the idea for the visual and symbolic part of the movie – to go from the Russian avant-garde to the anti-Communists dwarves. These influences exist of course in today’s world and are absorbed by young people. If you watch closely the compositions of some graphic novels you will realise they are based on the Russian avant-garde discoveries. And the graffiti writing from the 70s is still very popular today. So, in my movie I want to go back to the origins of those movements as a source of visual inspiration.

In terms of music, I have approached the neo-classical and ambient composer Julia Kent to score the movie. I love the way she mixes the classical composition with a new approach of processing and programming in music. This is what Julia has said about the project:

“Inspired by Jola Kudela’s artwork, which combines the organic and human with the technological, and by Aga Lesiewicz’s script, which spans time and place, I am planning to create music that uses organic instruments and sounds but intersects with technology in terms of processing and programming, the way my own solo music does. My own influences include a lot of ambient and electronic composers, and also 20th and 21st-century classical composers like Satie, Mompou, and the Minimalists. For the film, I think it will be important to create a world of sound where these compelling characters can tell their stories, which are so personal and also so universal, a backdrop that reflects the history they lived and the future they created.”

HN: You mentioned that you are aiming to attract a young audience from the age of 13 with the film. Could we hear ideas from both of you, from your roles as the director and the writer of the film project, on ways to attract that young audience? For example, how could a story dealing with Stalinism, Fascism and Communism make the young audience sympathise with the characters in the film and bring themselves into their story?

Jola Kudela: I know how strong the external influences can be on young people’s awareness. We are learning about the world through our own experiences but also through the information we receive. Film, graphic novels, books, music – they are the first source of information. Nobody likes to go to school and be bored to death at history classes. At least – that was my experience. But I loved to learn about history in a more vivid way and through stories of other people. As a child I have learned a lot from films. Some of it was true, and some was just a form of propaganda lie. For instance, Pharaoh (1966) directed Jerzy Kawalerowicz – a beautiful “hollywoodian” production about a young pharaoh who is trying to reform the Egyptian clerical society. Not only have I learnt a lot about Ancient Egyptians from this film, but also about the impossibility of winning a fight with a totalitarian system. It was, of course, a metaphor for what was going on in Poland at the time. On the other hand, there was also a very popular Polish TV series, Czterej Pancerni i Pies (1970) – about a Polish crew of a tank and their adventures during the WW2. It was a totally fabricated story about the Polish-Russian camaraderie – the only type of story that was allowed at the time. But there was nothing in the film about the brutality of the Soviet army, and for instance nothing about a wave of rapes and suicides of women along the line of the Russian front. Nothing about the fate of Marusia – a beautiful Russian nurse – who in real life would have probably been a front whore – as I have learned only recently from the amazing film, Beanpole (2019) directed by Kantemir Balagov.

What I’m trying to say is that the knowledge we are trying to “sell” to the young generations is very important. What is said and how is very important. And the film is a perfect medium for that, if we can keep the language attractive enough and accessible to the audience we are trying to speak to.

Our heroes are young – the viewers can directly identify with them and find themselves in their stories. After an era of abundant consumerism today’s young generation is becoming aware that something needs to change. But we have to be careful that there is no misunderstanding and that they are not turning against each other instead of working together. We can see those tendencies all over the world right now, and I feel the need to speak about it loudly.

Aga Lesiewicz: For most of the young people today Stalinism, Fascism and Communism are just abstract concepts, ideas that once held the world in their grip, but have lost their relevance. Which, of course, couldn’t be further from the truth – previous totalitarian systems may have failed, but the ideologies they were built on haven’t gone away. They are an ever-present threat to our world: the modern authoritarianism, with its new strategies of repression, media control, the spread of illiberal ideas through social media, the weakening of civil society and democratic institutions, and a swarm of populist politicians, is the old totalitarianism on speed. It’s far more toxic, because it’s insidious. It rewrites history for political purposes. And it takes over the world as we know it, while maintaining a veneer of legitimacy and order. The problem is that as long as we talk about ideologies as abstract concepts, they don’t seem like a threat. They seem theoretical, because they don’t have a face. And without individual faces history is just a distant place inhabited by dead people.

Our film tries to change that: it’s about historical facts filtered through human emotions: sadness, grief, anger, but also loyalty and love. It’s about individual experiences and attitudes, sometimes ugly, driven by fear, opportunism or political manipulation, and sometimes moving and uplifting, full of courage, dignity and integrity. And this is what is most interesting for me as a scriptwriter: going beyond the complexity of historical contexts in order to show the grey area of human emotions and behaviour. By doing so I’m hoping to draw in the young audience and make them not only sympathize with the characters, but also believe that this story could be about them.

HN: Could you let us know the most important characteristic and goal of the visual design of the story’s universe?

Jola Kudela: I think the visual design is key to attracting the viewer. We live in an image-based culture. With omnipresent phones, computers, billboards etc we are “trained” to respond to image – it’s a different part of the brain (visual cortex) than the one that responds to written language (visual word-form area). But even before the emergence of the mass media omnipresent culture – we knew how to recognise a bear and run away from it, than drew its picture, and much later write the word “bear” and contemplate it. So, it proves that a visual form of communication is primal and thus most effective. So, as I said earlier, I want to take the visual language of comic books and street-art and use its powerful accessibility to attract the attention of the potential viewer. In order to do so, I will use the visual grammar that we have accumulated during the last century – from the collages of Dziga Vertov, a Soviet documentary film director, to the bullet-times of The Matrix.