Synopsis

Amélie is a little Belgian girl born in Japan. Thanks to her friend Nishio-san, the world is nothing but adventures and discoveries. But on the day of her third birthday, an event changes the course of her life. For at that age, everything is at stake for Amélie: happiness as well as tragedy.

Amélie and the Metaphysics of Tubes is adapted from the novel by Amélie Nothomb.

Film credits

Directors: Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han

Scriptwriters: Liane-Cho Han, Aude Py, Maïlys Vallade, and Eddine Noël (adaptation from The Character of Rain (original French title: Métaphysique des tubes) by Amélie Nothomb)

Artistic director: Eddine Noël

Producers: Nidia Santiago (Ikki Films), Edwina Liard (Ikki Films), Claire La Combe (Maybe Movies), and Henri Magalon (Maybe Movies)

Executive Producers: Jean-Michel Spiner and Mireille Sarrazin

Music: Mari Fukuhara

Technique: 2D digital

Running time: 77 minutes

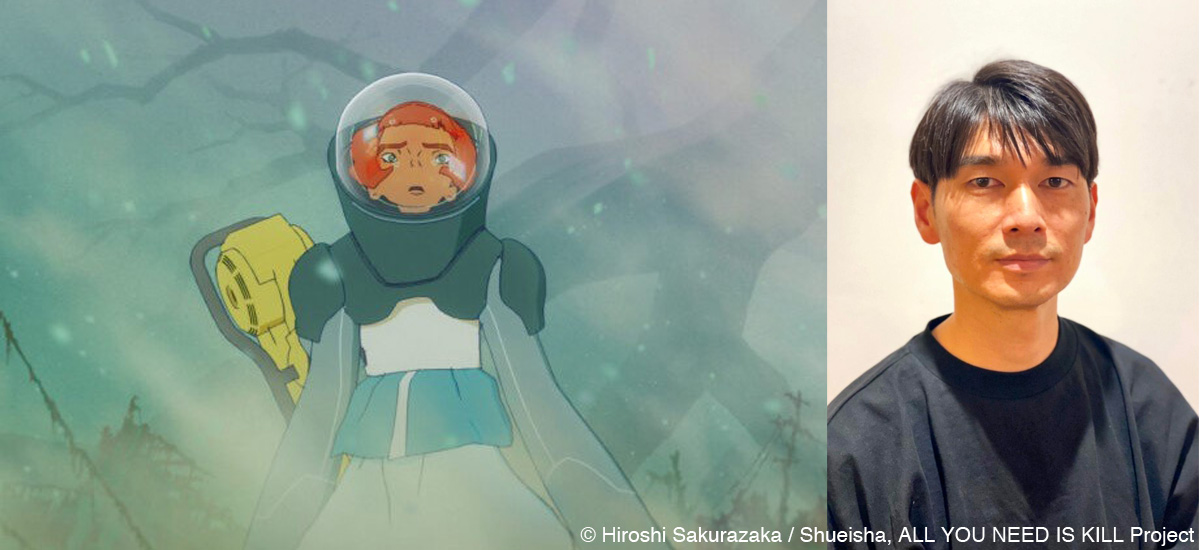

Little Amélie or the Character of Rain (original French title: Amélie et la Métaphysique des tubes) is a beautiful 2D animated feature film based on a semi-autobiographical novel by Amélie Nothomb. The film tells a touching story of a cute and curious Belgian toddler girl named Amélie, who interacts with adults that have experienced sadness and oppression. The story is set in Japan during the 1960s. It is the first animated feature film directed by both Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han.

The film premiered in the Special Screenings section at the Cannes Film Festival 2025 and won the Audience Award in the Official Feature Films Competition at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival 2025.

We interviewed Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han on the story behind the film.

Interview with Maïlys Vallade and Liane-Cho Han

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Is there anything in this film that you specifically want global audiences to pay attention to or enjoy while watching?

Maïlys Vallade: Yes, empathy is the driving force behind this film: openness to others, both culturally and emotionally. It is understanding a young child who is unique, and a person who has experienced oppression, war, and loss, both as an adult and as a child.

One of our goals was to make people from other cultures understand what it feels like to be uprooted, to lose your bearings at a formative moment in your existence and identity. The first traumas that mark us at such a young age, when we are already fully aware of our senses. We wanted to be able to talk to children about difficult things without underestimating them.

The novel we are adapting has a universal appeal. It takes place in Japan, but could have taken place anywhere else. This is not only because of its comprehensive and unique view of the world, what it means to lose something important, to finally understand and accept what has happened, but also because of ability to use the positive keys sown around us by people who are open to the world and to others, rather than the negative ones brought about by closing ourselves off, which can destroy us or freeze us for many years.

Finally, and most importantly, always finding a way to remember what has shaped us, accepting all facets, even the loss of all control, and understanding that we must open ourselves up to the world and to surprise, is something that can be absolutely enriching and often vital.

Liane-Cho Han: Not much to add more, everything is pretty well said. I would add acceptance. Acceptance that everything is ephemeral, everything has an end. That despite all the challenges we can meet in life, like disillusion or even death, life is worth living. That we should be more open to the world instead of being closed in ourselves, because we are too scared to suffer or too angry to let it go. And I totally agree about empathy. Empathy for children could maybe solve the worst conflicts.

HN: Which part of the original story from the book particularly attracted you, and how did you reflect that in the film?

Maïlys Vallade: For me, there are two moments that I can’t decide between.

Obviously, there’s the scene where Nishio-san talks to Amélie about her experiences during the war. In the book, this part is astonishing and macabre. Amélie is not afraid to confront this story by asking for more details because she wants to understand everything (we couldn’t transcribe it in such a raw way). Amélie wants to hear this macabre story; she doesn’t want to be taken for a “little girl.”

In fact, just before this, in the book, she starts speaking perfectly and for the first time to Nishio san in Japanese. This is something we were unable to keep, unfortunately, for several reasons, notably due to concerns about the structure of the new film narrative, but also for reasons of international translation, so that children could also fully understand what was being said.

It is a fragile and intense moment, where she finds a positive outcome to her grief through Nishio-san and her story, through memory and celebration.

The moment that always stays with me is that suspended moment when she returns from the beach and becomes aware of her own mortality. It’s something very profound; you don’t see things in the same way after that. She also understands that it’s important to have connections with the people around her, that without others, you cannot survive.

Liane-Cho Han: For me it’s this disillusion that Amélie has around the end of the book. When Nishio san leaves, and Amélie is begging her to stay. When she discovers that she will eventually leave Japan, that she’s not Japanese. That part always made me cry when I read it.

In the film, it was of course treated in a very different way. But we can still feel Amélie’s suffering and how the world collapses under her feet, but those two moments are more apart compared to the book.

We still have this intense argument between Kashima-san and Nishio-san witnessed by Amélie that cornered Nishio-san to have no choice but to leave. And the moment when she realized she has to leave Japan is combined with the Koi gift for her birthday, which also will lead her underground.

HN: Please tell us about the division of roles between the two of you in directing this film.

Maïlys Vallade: The adaptation process was particularly complex for this book, which covers many major themes and required a thorough interpretation of the overall structure of the narrative, as well as the need to translate the author’s dazzling, caustic, and generous literary style into phantasmagorical and sensory images.

The reflection and writing process took a very long time. I co-wrote the final version with Eddine Noël (who is also our artistic director) and Liane Cho.

This situation led us to move extremely quickly in the production process, and our roles as directors had to be split by the producers in order to be efficient and move forward completely in parallel, in 14 months. Usually, on other films we have worked on for a long time, we had between 18 and 24 months. Finally, a Lead had to be appointed so as not to waste any time, going into production in 2023.

My role was that of “lead” director, which meant I was responsible for overseeing the film’s overall narrative vision. I was responsible for the final version of the script and dialogues, directing the character design, storyboard, and animatic with our editor Ludovic Versace, the voices (by recording most of my own voices as references, which were used to manage the rhythm of the dialogues and the animation until the end), and the sound and music direction (joint musical preparation with Ludovic Versace and construction of the dialogue and instructions/explanations with our Japanese composer Mari Fukuhara).

During production, my contribution included graphic development, storyboarding, character design, colour reinforcement for the sets, FX animation reinforcement.

We were looking together for the sets with Eddine for instructions and validations.

Liane-Cho Han: Indeed, because of the intensive situation, with artists which has already started before the end of the animatic, I had to take care of them to be sure that the narration was well translated. Because of the rush, the storyboard were very rough and this film demand a lot of precision in terms intentions and emotions.

But luckily we worked with this artistic and production family for more than 12 years now, since Longway North. They are people we trust and know the style. With this very challenging production, we wouldn’t have made it on time without them.

HN: I’d like to hear the story behind your scriptwriting, such as:

What difficulties or challenges did you experience, and how did you deal with them?

What did you most aim to achieve in the script, and what did you take particular care with?

Did you talk or discuss anything with the author of the original novel, Amélie Nothomb about the film’s story?

Maïlys Vallade: Amélie Nothomb, the original author of this fictionalized autobiography, gave us a free rein for this adaptation and our first film, which is great for a director and quite rare. She told us, “My books are my children, the adaptations of my books are my grandchildren, and I don’t get involved in how my grandchildren are raised!”

We encountered many challenges, which we cannot list all, of course, but we can discuss several key moments in the construction of the narrative:

– Target audiences

– Voice-over: the need for a storyteller’s voice

– Graphic ambition, visual representation

– Point of view / child’s eye view / sensory

– Budget

The adaptation of the book and the writing process were very challenging at many levels. We analysed a lot, read the book many times, and two major versions of the screenplay were rewritten entirely. For this filme to be seen by a large target audience (grown-up and children), we had to find a good balance everywhere: between reality and fantasmagoria, narrative voice / first person voice of Amélie, the presence of Amelie’s voices—not too much so as not to be unfriendly, and not too much absent so as not to feel empty and lonely.

To extend this long work of writing, I needed to record my reference voices (our editor recorded his own for two characters too) and use them until the end of the animation, to be able to modify some dialogues anytime. We recorded the dubbing of French actors at the very end of production.

And of course, the whole structure: the book is a succession of life events, but we needed to create a totally new structure of the story in three acts, around the relationship of Nishio-san and Amélie, through the difficult themes of death and grief in post-WW2 Japan of the 1960s. There is this special cinematographic point of view at the height of a child, to connect with our sensorial approach and this very special gaze on things around, to evoke the reminiscing of childhood, and immersive nostalgia.

We needed to cut some big moments of the book, all the father ones for example (too expansive unfortunately), which were really interesting because of his close interest in Japanese culture (he was a traditional Noh singer). We regret a lot that!

And we also needed to transform some characters, like Kashima-san, who’s not the house’s owner in the book but a second housekeeper. In the book she is already this ancient aristocrat who lost everything since WW2. We really wanted to build a stronger story for Kashima-san and between her and Nishio-san, where Nishio-san can confront her in the end. This part was very difficult to manage, the balance of the argument scene between these two, and also the choice to keep the same language everywhere, to be understood by a young audience too. We accepted losing the Japanese language so the viewer would be immersed in Amélie’s perception.

In the book, André and Kashima-san didn’t save Amélie. It was a choice for simplification and for the biggest moments of Amélie’s awareness.

The storyboard and editing process was also very challenging and was in confrontation with the writing structure. When we had just finished the animatic with our editor Ludovic Versace, 86 minutes of the film!, it worked very well, but we needed to cut almost 20 minutes of it to fit the final budget, even though we were in full production. It was a lot! (a nightmare) The scariest thing in production for me! (we kept 68 minutes of images)

Liane-Cho Han: Indeed, pretty much everything has been said. The script was the most challenging of all. Also because when it’s about adapting a book, everyone has their own interpretation. For example, already at the very beginning, the concept of God was a problem as everyone has an opinion of what God is. Because of those disagreements, there was a lot of mislead during the writing process, especially for the structure of the film, what leads the character of Amélie through the film.

And I don’t even start with the target, as Maïlys has said pretty much everything. We wanted to make a film that is transgenerational, that could move adults and also children despite the complexity and the harshness of the themes. But in this world, everyone has an opinion about what a kid can understand and handle.

HN: We see much animation magic throughout this film, such as everyday occurrences transforming into grand or fantastical moments through a child’s imagination, and scenes that visualise literary expressions or intangible feelings and emotions conveyed through words with rich expressiveness.

Could you please tell us how you achieved these, including the visualisation process and key elements for creating them?

Maïlys Vallade: First of all, when writing, we wanted to establish a very precise framework in terms of timing and intentions, estimating and counting every minute of film as soon as we had finished a structure that could work.

Using Miro software, once we had structured everything using coloured labels for small scenes (imitation Post-it notes), we established a timeline covering one year, with dates and seasons indicated. The first two years pass very quickly.

On this timeline, we indicated which scenes could be set during the day or at night, in order to give the right rhythm to the lighting in the film, which plays a very important narrative role along with colour, reflecting Amélie’s perception and her different stages of understanding.

On this timeline, we also added stars at moments chosen according to when the intention allowed for the development of a phantasmagoria. Concepts were developed by the graphic team to find the best possible symbolic image rendering at child height.

We developed our first sensations, and so when she comes into full possession of her body, everything becomes exceptional and disproportionate, amplified. It therefore seemed obvious, for example, during the spring and garden episode, that everything around her had to become very large. We could play with Amélie’s proportions according to her emotional state at the time, until she lands and returns to reality and the simple, wonderful, and fascinating beauty of nature itself.

There are also these mainly symbolic scenes that are not fantasies but develop a more sensory approach, such as the discovery of the lychee spinning tops. In the book, there is only one spinning top, but Simon Dumonceau, one of our colour artists and graphic co-authors, had this memory of doing this as a child on his table. It was great because it was exactly what we needed to symbolize the two soul mates Amélie and Nishio-san in this gravitational rotation, whose cycle eventually ends, but whose wonderful rotation remains sublime in Amélie’s memory.

The goal was to recapture those very simple and fleeting moments of life, from our own childhoods and sensations, which are usually almost completely forgotten as we grow up. We wanted to develop as many nostalgic scenes as possible in order to amplify this work of memory.

Liane-Cho Han: Indeed, a lot of people from the team have collaborated from their own childhood memories. Between the two versions of the script, Justine Thibaud and Simon Dumonceau, led by Eddine Noël, brainstormed and crafted many concept arts ideas for most of the fantastical moments, like the bubble or the jar that inspired a lot the second and final version of the script.

We always wanted to be in Amélie’s POV, to see the beauty of the world through her eyes. But not only the fantastic moments are “fantastic”. We also wanted the more grounded moments to have some fantastic feelings. For example, when Amélie and family are driving back home from the beach, the way she observes the raindrops vibrating on the window because of the wind and shining from the sunset. We needed those grounded moments to feel magic too.

HN: The colours in this film are very impressive: sometimes they create a bright atmosphere, give us a fantastical impression, and transparent and pure scenes appear.

Could you tell us about the creative process that led to the film’s colour palette, as well as its purpose and specific intentions?

Maïlys Vallade: The choice of colours was very decisive in the process of representing the gaze of a very young child.

The film also plays with the naivety that emerges from it to contrast with the depth of the narrative, illustratively, in a form that sometimes appears simplistic and refined (which is often the most difficult thing to achieve accurately).

At first, the colours were meant to represent the world as seen through the eyes of a newborn: highly overexposed, then pastel but very vivid colours, reflecting the full euphoria of early childhood. Little by little, with the realization that things are not as Amélie idealized them, they become distorted, moving towards increasingly realistic and sometimes desaturated colours at the time of autumn and her fall.

As I said earlier, light plays a major role in Japanese homes. The structure of this house, with its shoji doors that filter the light and instantly create a very intimate atmosphere, gives substance to the scenes pierced by rays of sunlight, which symbolise the arrival of the saviours: first the grandmother, then Nishio-san.

An idea from our art director was to also design colour themes to each characters. For example, Kashima-san wears purple to symbolise melancholy, Amélie wears the green of her little pond water, Nishio-san wears the warm yellow/ochre of the sun because she’s Amélie’s sun, her brother André wears red, and so on. At the end, when Amélie loses her landmarks, all the characters’ colours are mixed together, creating an unconscious feeling of confusion that accentuates her loss of direction. Each scene and atmosphere is enriched with this colourful symbolism, until we feel the acceleration and rhythm of these colours until the end of the film and the stabilisation in reality, a reality that is just as fabulous.

Liane-Cho Han: Again, pretty much everything has been said here about the colour intentions. Of course, our roots also come from the films we have worked on before like, Longway North and Calamity, which also have a very strong colour palette with an impressive touch. And naturally, the technique and intentions were adapted for this new film.

HN: What research did you do on Japan for this film? And how did your research influence the film’s story?

Maïlys Vallade: Our graphic family has one thing in common: we are all very close to the movement known as Japonism, a rich exchange and artistic and cultural love that has brought France and Japan closer together since the Impressionist era, with artists communicating with each other, such as Henri Rivière in France and Hasui Kawase, but there have been many others.

Our artistic director Eddine Noël, who knows Japan well, conducted extensive research on the locations where the film takes place, particularly in the Kansai region near Kobe, on the mountainside and in a natural setting that is rich for the senses. He conducted particularly rigorous research on the types of shrubs, fauna, and flora in the locations studied, all the way to Tottori Beach.

A study of the famous Japanese gardens and the symbolism they offer, such as the river of aligned pebbles, which in the film symbolises Kashima-san’s heart and her feelings frozen in time after the loss of her loved ones during the war.

A visit to the Albert Kahn Japanese Garden in Paris provided a fantastic setting for documentation (to experiment with outdoor gouache sketches) organized by Eddine Noël for Justine Thibaut and Simon du Monceau, our main colour artists. We kept numerous photographic archives from the visit.

Research was also conducted on the cultural contribution of Japan to the film’s key moments: the theme of this strange god, and death through mourning. Some scenes are not in the book, so we had to create them, such as the reading scene and the Yokaï Otoroshi (who protects the gods), which alludes to his affinity for books, through the approach of Nishio-san, who immediately recognises the child’s intelligence and curiosity.

We also created the Obon scene, which does not exist in the original. We needed a scene that would provide a positive key and symbolic elements such as the lantern to lead Amélie towards acceptance. Amélie Nothomb herself told us that she had actually experienced this and was amazed that we had added it to our adaptation.

Creation of the Kanji ‘Amé’ scene, the Japanese character for rain, traced on the glass surrounding the Engawa (glass corridor around the house). And finally, above all, this traditional Japanese house, designed entirely by Eddine for our staging and lighting needs, but with typically Western objects that could be found in the 1960s for Belgian expatriates.

The Japanese ideal completely permeated the film, down to the smallest detail of texture that Amélie touches. We wanted to be as respectful as possible of this rigorous culture.

Note: There is also a famous documentary that traces Amélie Nothomb’s childhood during this period: Une vie entre deux eaux by Laureline Amanieux (leave the title in French as there is no English version), which helped us to reconstruct her family and Nishio-san. Unfortunately the house from that period had been demolished, so Eddine had to recreate it. The documentary shows the reunion between Amélie and Nishio-san 30 years later, which is extremely moving.

Liane-Cho Han: Yes, we definitely need to acclaim Eddine’s work on this. Every elements were thought of very precisely. The vacuum cleaner, the fridge, all the props existed at that time, in that area.

We received so many compliments from Japanese people, after watching the film, who really felt like home. From what they said, usually, when Western people picture Japan, it always looks like China. But not this time. They really felt like they were at home in Japan.

HN: I felt that the music strikes an excellent balance between Western-esque, universal melodies and distinctly Japanese compositions, perfectly matching each scene in the film.

Could you please let us know how you achieved that with Mari Fukuhara?

Maïlys Vallade: That’s exactly why we needed a Japanese composer; she really is the Japanese soul of this film! Her compositions are truly tinted with her culture; she really made her mark on this project. We had references from a wide variety of composers, such as Masakatsu Takagi, Yoko Kanno, and Dan Romer, for example (I’m particularly a fan of the film Beasts of the Southern Wild), but also Cecile Corbel, Dan Golding, and many others!

The big challenge for our composer, Mari Fukuhara, was that we used reference music until very late in the film’s production, which was often very precisely calibrated to follow a very rigorous edit, which Mari had to make her own. We created a very precise musical structure with Ludovic Versace, our editor, as well as an outside friend who guided us through many sometimes complex instrumental references related to Japan and our symbols.

To do this, I had to put together a very dense and comprehensive document (to be translated from French into English, and then into Japanese), which aimed to convey the precise but succinct intentions by theme (accompanied by colourscripts), so that she could find her room for freedom. She was very creative despite this and accepted all the challenges, including compositions with a wide variety of instruments reflecting several different cultures, the interpretation of Ravel on the piano, the interpretation of Takeda’s traditional nursery rhyme, and the creation of a song (which unfortunately was recorded after the film, called Hana on YouTube!). She was accompanied by a Japanese orchestra, and the music was recorded at a conservatory in Tokyo.

In our film, music is not only conceived as a decoration or an accompanying element, but also for its narrative and symbolic value. The sequences were classified either by mood, symbolism, or both.

More details:

Some examples of these elements in conversation:

– Geographical, historical, and cultural tension

– East / West

– Modernity / Tradition

– Wartime / Time of peace

– Femininity / Masculinity

– Biological and geological tension (or tension between the elements of natural forces)

– Stable and harmonious nature / Unleashed, tumultuous nature

– Passive, protective, and conservative body / Active and creative body

– Body of power and joy / Body of sadness, unfulfilled desire, and impotence.

Symbolic tension:

Life / Death, Growth / Decay, Destruction / Creation, Active / Passive, High / Low, Fullness / Emptiness, Fluidity / Rigidity.

These tensions and the creative energy they generate could easily be associated with a certain theory of Taoist spirituality and its symbolism of yin and yang. Many musical arrangements were therefore conceived based on these articulations of concepts in “tension” or “dialogue.” For example, musical compositions that alternate between light, twirling, airy aquatic passages and more stable, muffled, terrestrial accompaniments rumbling like an earthquake.

The element of water in music:

To evolve and grow amid tensions, Amélie naturally adopts the characteristics of water. Water is the most emblematic and representative symbolic element in Amélie’s quest for physical and psychological power. It is the ambivalent element par excellence: protective yet destructive, mobile yet stable, creative yet adaptable, peaceful yet furious. Water is present in most musical creations. The choices were based on the sound characteristics of water: rounded tones, echoes, and sparkles that recall the sound of water droplets. Background motifs often feature repetitive arpeggios (in the impressionist style of Ravel and Debussy), evoking the flow of water.

Musical choices for the characters:

– Amélie: Music with aquatic sounds and tubular instruments, evoking her different mental and physical states. Power, powerlessness, distress, joy, discovery, introspection, etc.

– Nishio-San: String instruments, airy, light, popular, harmonious, soft. Inspiration: Cécile Corbel, Yoko Kanno.

– Grandmother: A free-spirited and eccentric character, almost dandyish. Eccentric, zany, and joyful.

Inspiration:

– Jon Brion Patrick: Music that conveys a sense of awkwardness, lightness, and humour.

– Danielle: Concert pianist, she works on Debussy and Ravel compositions on the piano.

– André: Something also clumsy, gruff, even brutal and unrefined. Representation of a primitive masculinity.

– Kashima-san: Traditional flutes that create dissonant effects (feelings of unease, rigidity, tension). Inspiration from Takemitsu.

We also used wind instruments, string instruments, percussion instruments, and electronic music. The instruments used in the test music were chosen based on the criteria described above. Large musical ensembles such as symphony orchestras were rarely used; instead, we favoured small, intimate, simple, traditional groups close to natural sounds—child-friendly and never epic, romantic, or grandiloquent.

Through these sounds, we aimed to support the allegory of the “tube” that structures Amélie Nothomb’s book and recurs throughout the film.

Additional details:

There are therefore a significant number of “tube” instruments: marimba, wooden xylophones (natural, Japanese), Koshi chimes (aquatic sound), traditional or classical flutes, clarinet, bassoons, transverse flute (evoking divine breath in the first part, symbolising a godlike Amélie), and shakuhachi (Japanese flute) for Kashima-san’s martial, dissonant, and sometimes unpredictable character.

Percussion was also prominent. To maintain coherence between earthly and heavenly sounds, we used small metal or wooden percussion instruments for their clear, light tones, evoking water: carillon (childhood, music box, extreme clarity, high pitch, already present in the teaser soundtrack) and metallophone (soft, metallic, cool yet aquatic, like rain or downpour). In contrast, large percussion instruments such as taiko drums were used for Amélie’s supernatural feats, power, and natural phenomena reminiscent of earthquakes in Japan—echoing Godzilla. Timpani and cymbals were also employed.

String instruments were used regularly to convey lightness, melody, airiness, and joy for characters like Nishio-san and Amélie’s grandmother, while producing enigmatic, unsettling tones for Kashima-san, the temple, and the carp.

Further details:

Plucked strings such as harps, guitars, and ukuleles (for lightness, good humour, community life, discovery, travel; bright and clear, also aquatic).

Traditional Japanese strings: shamisen (for an oriental sound, sometimes comical, dissonant, dysfunctional, or spiritual for the temple or yōkai).

Piano: treated as an impressionistic instrument with repetitive arpeggios, evoking the bond with the mother and, more broadly, with nature, femininity, and water. We avoided overly melodic or melodramatic piano use that would add sentimentality to characters’ emotions or situations.

As in Mari Fukuhara’s pilot compositions, the use of vocal elements (singing) and electronic instruments proved highly effective. These early works provided a solid foundation for the film.

Summary and conclusion:

Music is considered a character in its own right, a presence beyond the screen, a voice of nature that surrounds and influences Amélie, dialogues with her, and responds to her growing power over the world.

Liane-Cho Han: I don’t have anything to add. It was amazing to work with Mari Fukuhara. It was already an amazing discovery when she collaborated on the pilot many years ago and despite the distance.

We were so moved when we met her and her team in person for the first time in Japan a few weeks ago as Little Amélie was selected at the Tokyo International Film Festival. I’m convinced we will see and hear more of her print in the future.