Synopsis

Chiba Prefecture, Japan. The Boso Peninsula. A massive, unidentified plant from outer space, known as “Darol”, has spread its roots across the land, wreaking havoc with its electromagnetic waves and high-concentration gas, devastating the environment on a massive scale. To aid in the recovery efforts, volunteers from across the country and abroad have been randomly selected.

Film credits

Director: Kenichiro Akimoto

Screenplay: Yuichiro Kido (Adapted from All You Need Is Kill by Hiroshi Sakurazaka)

Producer: Eiko Tanaka (STUDIO4°C, Japan)

Character Design: Izumi Murakami

Art Director: Tomotaka Kubo

Music: Yasuhiro Maeda

Technique: 3D digital, 2D digital

Running time: 82 minutes

ALL YOU NEED IS KILL, Studio 4°C’s new animated feature film, had its world premiere at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival as part of the official screening programme ‘Midnight Specials.’ The film was also selected for the ‘Sitges Collection’ and ‘Anima’t’ sections at the Sitges Film Festival in Spain.

Based on a hit Japanese novel that has been adapted into both a manga and a Hollywood live-action film starring Tom Cruise, the new animated feature film tells an action-packed Sci-Fi story infused with mystery.

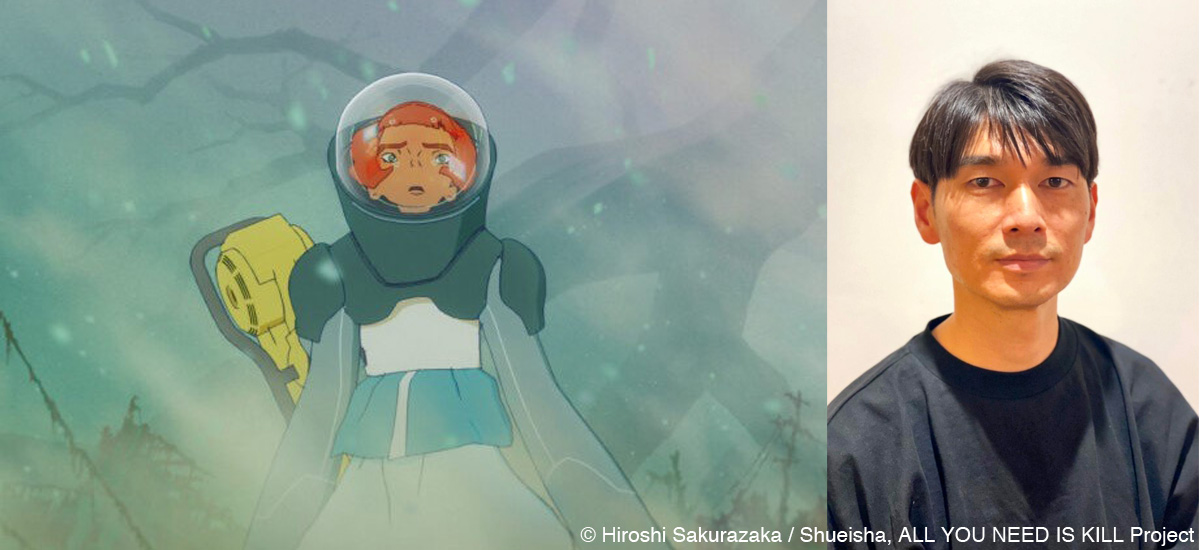

We interviewed Kenichiro Akimoto, the film’s director, on the story behind the creation of ALL YOU NEED IS KILL.

Interview with Kenichiro Akimoto

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): Which aspects of the film would you particularly like the audience to pay attention? What would you like them to feel or take away from the film?

Kenichiro Akimoto: This film is a time loop story, but even in scenes that appear similar, they are expressed in subtly varied ways in line with the protagonist’s emotions through inventive approaches. I hope the audience will notice how each viewing reveals new discoveries and gradually brings to light the staff’s meticulous attention to detail in every cut.

I would be happy if, after watching the film, the audience feels inspired to live tomorrow with a slightly more positive outlook.

HN: The original novel was adapted into a manga by Takeshi Obata and into a live-action film starring Tom Cruise in Hollywood. This time, it has been made into a feature-length animated film, marking the third time the story has been adapted into another medium.

Could you please tell us how the animation project began and how you came to be involved as director?

Kenichiro Akimoto: Warner Bros. Japan approached us with a proposal to adapt the original novel into a full-length animated film. Around that time, I had been discussing my desire to create a Sci-Fi film with the producer Eiko Tanaka, so we decided to accept the offer.

HN: In addition to the previous question, what did you see as the meaning or purpose behind adapting the original novel into animation again? Did you have any particular challenges in mind? Was there anything you specifically wanted to challenge yourself with that could only be undertaken through the medium of animation?

Kenichiro Akimoto: I faced a significant difficulty in finding the meaning and purpose of adapting the story into animation. The original novel, the manga adaptation, and the live-action film are all outstanding works that stand on their own. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that if we were to animate it, I wanted to do so in a style and expression unique to our studio.

Since both the manga and live-action film adaptations had a stylish aesthetic with camouflage colours, I wanted to take a different visual approach for this film and depict the cycle of life and death beautifully within vibrant landscapes. Inspired by Tanaka’s early concept of “a giant flower blooming on Earth,” I developed rough visuals and built the story universe for the animated version of ALL YOU NEED IS KILL around that idea.

HN: If there are any differences between the film’s story and the original novel, could you please tell us what your intention was behind those changes, and what you paid particular attention to during the adaptation process?

Kenichiro Akimoto: Adapting the original story was one of the major challenges during production. I repeatedly asked myself, “What do I want to convey to the audience through this film?” and made adjustments to the story accordingly.

I was thinking of making the film leave the audience feeling even slightly more positive, even though the story involves repeated deaths. However, during the early stage of structuring the narrative, the tone became rather dark.

It was after Yuichiro Kido joined as screenwriter that the characters and story gained vibrancy, and I began to feel the potential for the film to function as a proper cinematic work.

Hiroshi Sakurazaka, the author of the original novel, was very open to our adaptations and accepted many of our story ideas. There was only one request he made: “Please create a work with a solid Sci-Fi setting.” To fulfil this, Yuya Takashima, a Sci-Fi author and science consultant, devised a brilliant setting that works effectively within a Sci-Fi entertainment piece.

HN: The visual designs of the aliens, powered suits, and weapons differ across the original novel, the manga, and the live-action film.

What did you focus on when designing these elements for the animated film, and what was your intention behind that?

Kenichiro Akimoto: The powered suits were initially designed by IZMOJUKI, and then re-arranged by Izumi Murakami to match the character designs.

For the aliens’ visuals, we drew inspiration from flowers, ancient starfish, and large excavation machines, aiming to express an eerie yet mysteriously alluring beauty. In the original novel, the creatures are civil engineering machine lifeforms that terraform planets and invade Earth by attaching themselves to marine echinoderms. We also incorporated that story setting into their visual design.

We ensured that all designs had clear silhouettes and could move fluidly and vividly when animated.

HN: The visual design of the characters and the colour palette for this film feel distinct from current mainstream trends in anime. Could you please let us know why you chose Izumi Murakami for character design, and what kind of requests you made to her?

And in terms of the film’s colour palette, what did you particularly take care with and pay attention to, and what aspects did you focus on?

Kenichiro Akimoto: I’m glad to hear that you felt the film has a unique personality that differs from mainstream trends in Japanese commercial animation.

I had previously worked with Murakami-san on Children of the Sea (2019) and Fortune Favours Lady Nikuko (2021). Since I feel that 3D animation often results in somewhat stiff movement and silhouettes, I wanted to challenge that by incorporating Murakami-san’s fluid and elegant silhouette drawings into a 3DCGI project. That’s why I approached her for character design.

Regarding the protagonist Rita, we experimented with various character styles from the perspective of “what kind of personality she might have and how she would express herself,” starting from the early project stage when the script was not yet completed. I found an actress who matched my image of Rita, and I asked Murakami-san to expand on that image by using a TV drama character she had previously portrayed as a starting point. This process led us to the final design of Rita, a woman who does not easily offer a smile to flatter others.

Initially, Rita’s visual design was relatively photorealistic, but her silhouette gradually became more sophisticated. I believe Rita’s visual has been completed as a superb design, rich in emotion, and although the style of visual expression is flat, her personality is clearly conveyed even through the silhouette.

As for the colour palette, I developed it in collaboration with Art Director Tomotaka Kubo and Colour Designer Konoha Suzuki. Since I adjusted the colours of the world that Rita sees to reflect her emotional states, I requested that colour scripts be created for each scene.

Hence, we prepared a substantial number of colour scripts, which enabled all team members to share a unified image of the colours for each scene and the overall work from a bird’s-eye view. This made the production process smoother.

Suzuki-san even created scene-specific, and at times cut-specific, colour instructions for most of the colour scripts, making this project the one for which she prepared the most scene colours. I’m truly grateful for all her hard work.

When I checked the 3D animation rendered with scene colours, the impression of the screens I had been reviewing with basic colours dramatically shifted to the atmosphere I was aiming for in the film. That experience reminded me of the power of colour.

Regarding the visual direction of the background art, which is the core of this film, I worked closely with Art Director Tomotaka Kubo and Screenwriter Yuichiro Kido to fine-tune the visuals, as we developed the script, storyboards, and art settings simultaneously. Kubo-san and I share similar tastes in film aesthetics, and we often referred to films from the 1990s to early 2000s. He created truly exceptional background art for this film.

Regarding the characters’ visuals, Suzuki-san designed the colours based on art boards and colour scripts. I asked her to draw inspiration from several paintings, photographs, and French bande dessinée to determine the basic colour direction for the characters. For Rita, we ensured that her beautiful red hair would stand out in every scene.

HN: The film’s numerous action scenes are gripping, with a strong sense of speed and dynamism. How did you design the character movements and camera works for these scenes? Could you share your creative process for the action sequences?

Kenichiro Akimoto: For the action scenes, I dipicted them by setting one rule: Rita’s abilities should evolve in line with her growth.

So, the action scenes I planned for Rita begin with her only being able to run and flee on the ground. As she grows through repeated time loops, the range of actions she can perform expands, and eventually, we depict her leaping across tree roots and soaring through the air to confront the creatures with ease.

The camera work — from a first-person perspective focused on Rita’s feet to a wide view that stretches across the sky — is linked to the broadening of Rita’s field of vision and her emotional shifts, both of which accompany her growth.

Each of my imagined action scenes was then transformed into a concrete sequence by the CG animators, including Nakamura-san, Tokumaru-san, and Nakajima-san, who were in charge of the action scenes. I always looked forward to reviewing the stylish and inventive sequences they created.

HN: Although this is a 3DCGI film, the final visuals resemble very natural 2D animation. Could you please let us know about the technical aspects of the production process, including any particular challenges or areas you focused on?

Kenichiro Akimoto: One major challenge was how to translate Murakami-san’s 2D character designs, which are an essential feature of this film, into 3D models. The design illustrations of Rita and Keiji were so attractive that we repeatedly adjusted the modelling and rigging to capture their charm as closely as possible.

The CG team, including Imanaka-san, created captivating 3D models by applying fresh ideas and techniques. Animators commented that it is rare to see 3D models that get us this excited the moment they are loaded into a scene.

The appeal of the 3D models of the characters was key to realising ALL YOU NEED IS KILL as a film, and it gave me a sense of the potential of character creation in 3D animation.

Next, I’d like to talk about Co-director Yukinori Nakamura. With extensive experience in 2D animation projects and deep knowledge of 3D animation, he served as a bridge between myself and the animation directors Hisato Tokumaru and Tomonari Nakajima. He understood my intentions and managed our communication with precision.

Nakamura-san handled a variety of tasks with incredible speed and quality, from the production pipeline flowchart and design asset management to the development of support tools for Maya and animation check-back. He performed animation check-back for every cut in the film and created nearly 1,000 reference sheets.

About 20% of the film’s cuts involved retouching rendered characters, ranging from major revisions to minor adjustments such as cloth penetration and silhouette refinement. Under Nakamura-san’s direction, even small tweaks instantly removed the “3DCGI feel” and proved highly effective.

Thirdly, I’d like to talk about ANIMEGOKIN-V, a CG studio led by Hisato Tokumaru, one of the animation directors on this film. This was my first time working together. The studio is home to a small but highly skilled team of animators, and they developed animation of truly outstanding quality. To the best of my knowledge, I was left with the impression that the quality of their 2D limited animation created using 3DCGI is among the finest in Japan. Tokumaru-san, along with Takuro Togo and the rest of the team, always focused on how to improve the final visuals. I felt that this mindset aligned with Studio 4°C’s approach to filmmaking. I was happy to see that the passion they poured into refining each cut right up to the last possible moment within the limited schedule really comes through in the finished film.

Next, I’d like to talk about Tomonari Nakajima, another animation director on this film. He previously worked at Studio 4°C, where he was one of my senior colleagues, and has contributed to a wide range of projects alongside many of Japan’s renowned directors. The first time I had the opportunity to work with him was on the Berserk: The Golden Age Arc trilogy.

For this film, aside from the team at ANIMEGOKIN-V, the rest of the animation staff, including freelance animators and in-house artists at Studio 4°C, worked under Nakajima-san’s direction. While checking the animation from his own team, he also personally handled more scenes than anyone else on the project. Moreover, he took the time to teach the fundamentals of animation from scratch to our younger animators at Studio 4°C, helping them raise their cuts to a level of quality on par with the rest of the film.

The compositing direction for this film was entirely handled by Takanori Nakashima, who served as both the CGI Director and Director of Photography. I personally believe that compositing is a crucial process, as it determines whether the final look of the animation can reach the level of a theatrical feature. In every cut, the impression of the visuals changed dramatically before and after Nakashima-kun’s compositing work. All the animators said, “My cut now achieved film-quality standards.”

I have a few thoughts on why his compositing gives the visuals such a cinematic aura. One key feature of his style is that, regardless of whether the work is 2D or 3D, his strong foundational skills allow him to bring out the best in each visual element, such as background art, character animation, and effects, while clearly understanding the key points to highlight in each shot and reflecting that in the final image. And I believe Nakashima-san adds a refined, analogue film-like texture to the finished visuals by applying photographic processing with a particular focus on how to capture “light” beautifully.

HN: I would like to ask about the music. Could you please let us know how composer Yasuhiro Maeda joined the project, and what your collaborative process with him was like?

Kenichiro Akimoto: Tanaka-san introduced Maeda-san to me, and as soon as I listened to his demo, I immediately decided to offer him the role. Not only is the quality of his musical pieces outstanding, but he was also incredibly flexible in responding to my requests. Even when I made unreasonable demands due to my lack of musical knowledge, he would prepare multiple options to choose from, which made the collaborative process extremely smooth.

After composing the wonderful scores, Maeda-san remained fully committed through to the final stages, including the orchestral recording and sound mixing. He worked closely with me right to the very end. I’m truly grateful for that.