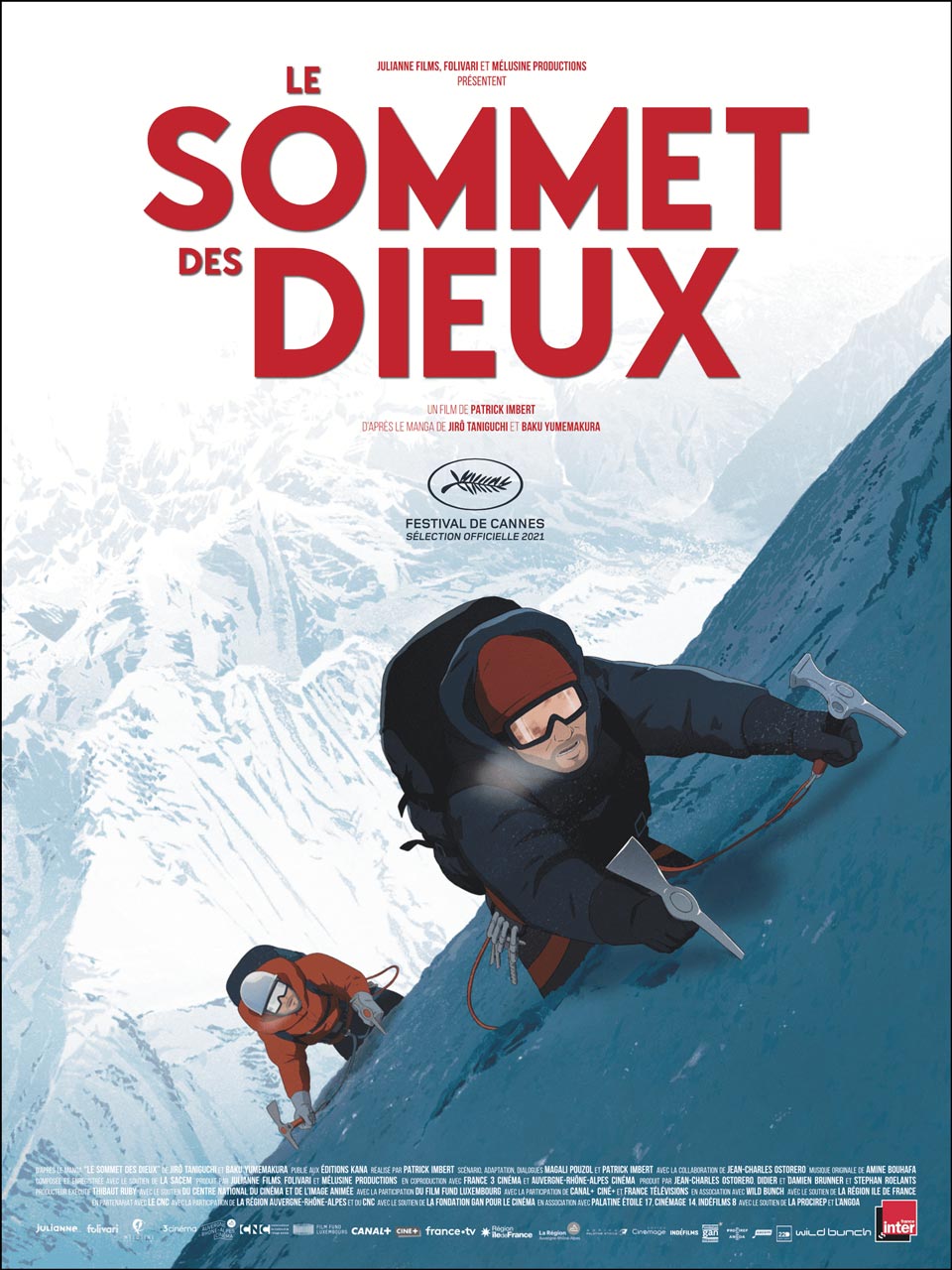

Synopsis

Were George Mallory and his companion Andrew Irvine the first men to scale Everest on June 8th, 1924? Only the little Kodak camera they used to photograph themselves can verify the truth. In Kathmandu, 70 years later, a young Japanese reporter named Fukamachi recognizes the camera in the hands of the mysterious Habu Jōji, an outcast climber believed missing for years. Fukamachi enters a world of obsessive mountaineers hungry for impossible conquests, on a journey that leads him, step by step, towards the summit of the gods. A thrilling adventure set against breath-taking Himalayan landscapes, inspired by real events and adapted from Jirō Taniguchi’s bestselling manga.

Film credits

Director: Patrick Imbert

Authors: Patrick Imbert / Magali Pouzol / Jean-Charles Ostorero (Adaptation from The Summit of the Gods by Jirō Taniguchi and Baku Yumemakura)

Producers: Jean-Charles Osotorero / Didier Brunner / Damien Brunner / Stéphan Roelants / Thibaut Ruby

Music: Amine Bouhafa

Production companies: Folivari (France) / Mélusine Productions (Luxembourg)

Technique: 2D digital

Running time: 90 minutes

The Summit of the Gods is a film that reaffirms the potential of animation for adults that is being explored with enthusiasm by the European animation industry. The film tells a universal story of the noble but melancholic journey of a highly experienced mountaineer with his life-long quest to scale dangerous mountains that reach to the heavens.

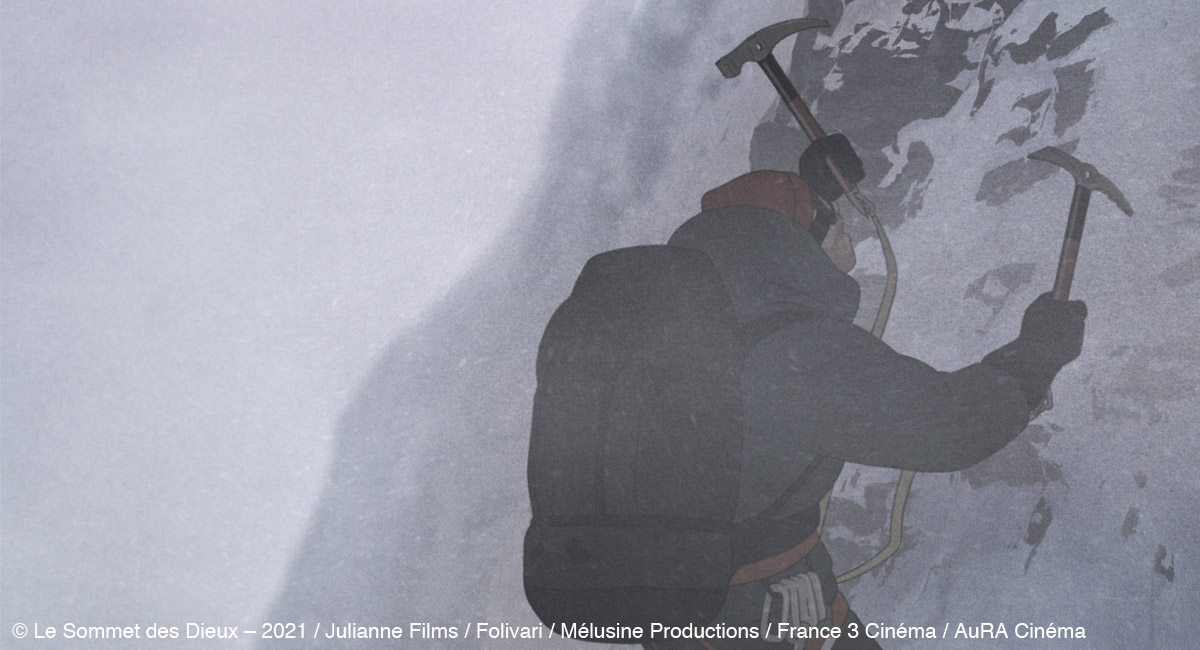

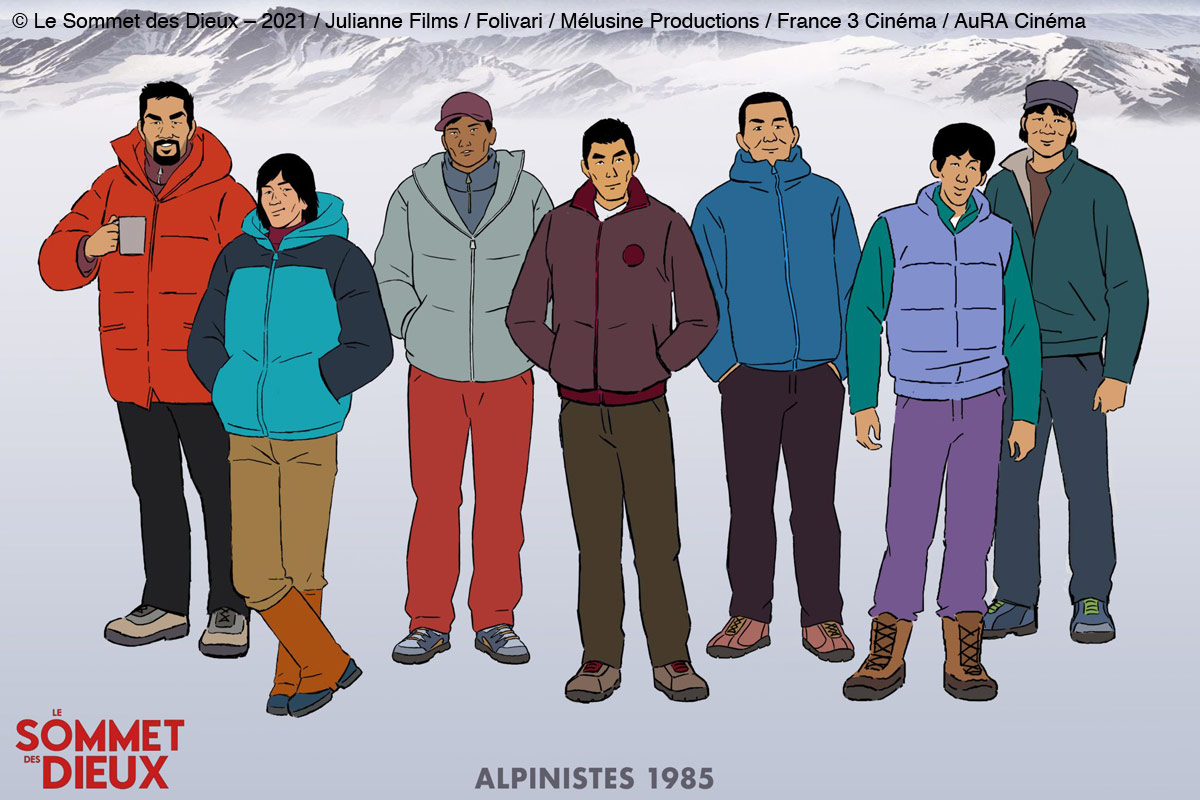

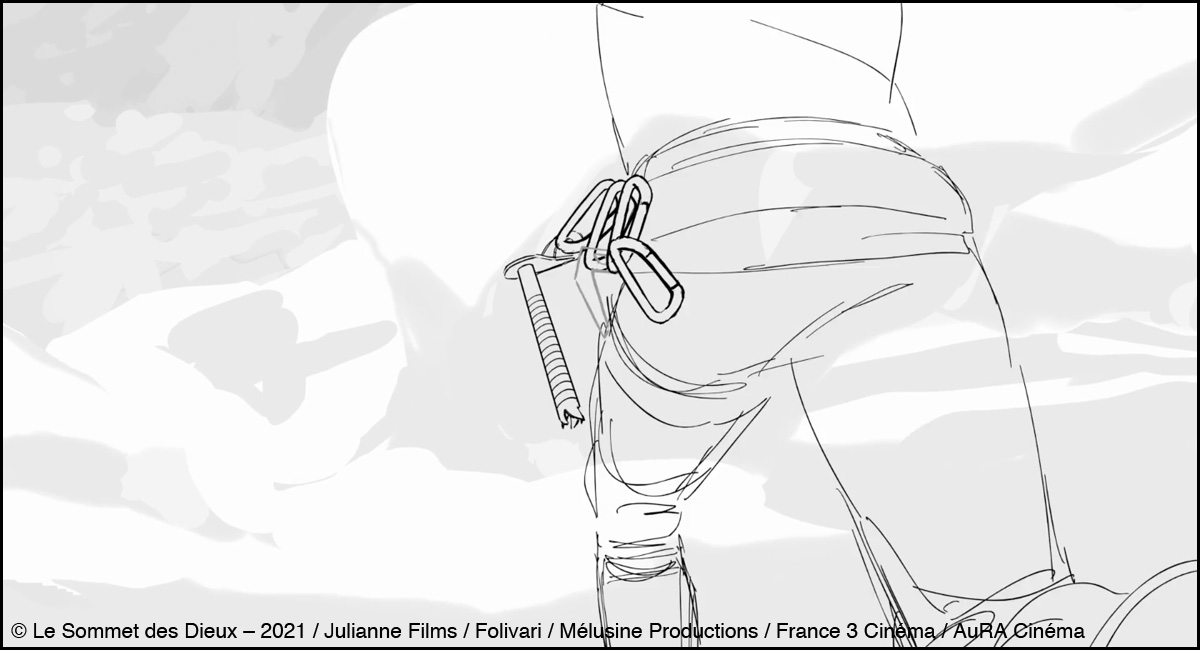

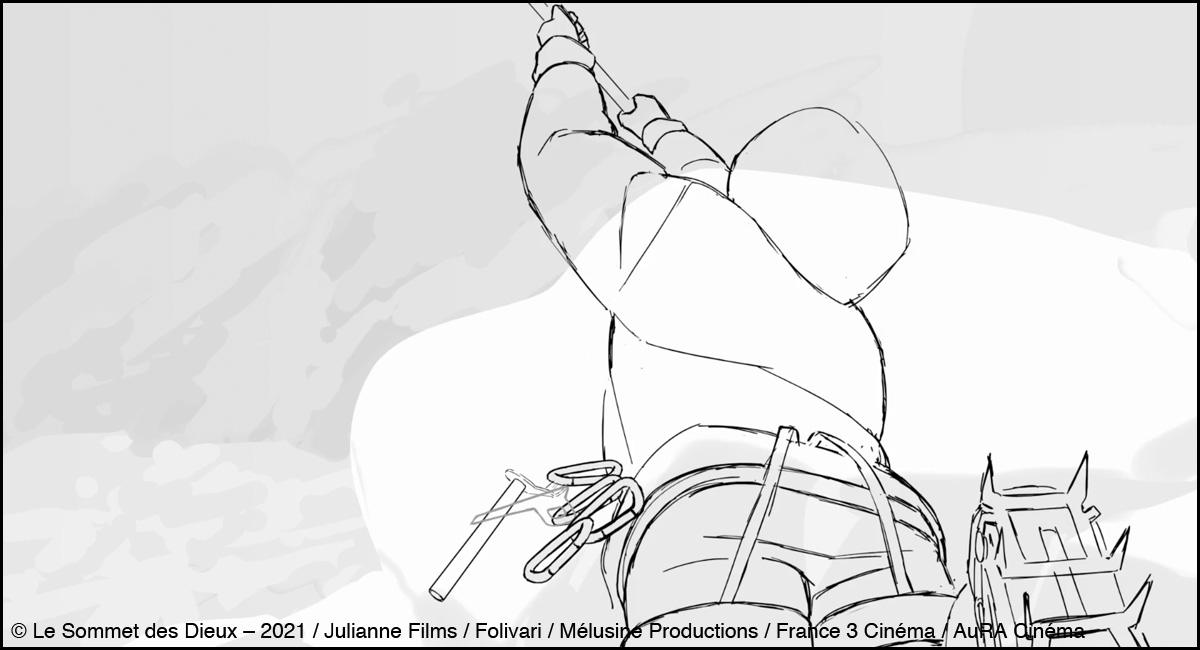

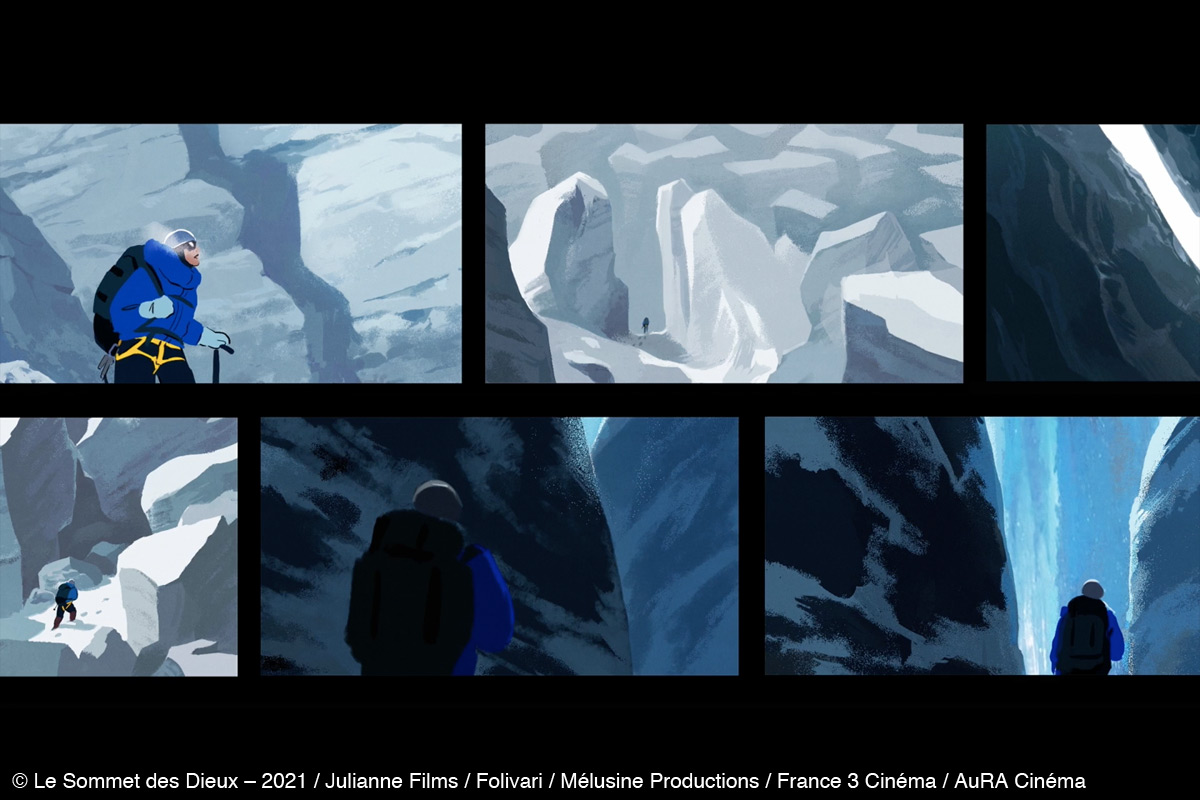

For the film’s visuals, the characters with well-balanced design between realism and stylization were animated with finesse to achieve a level of acting and emotional expression suitable for the film’s mature story. The background art enables the audience to feel the atmosphere and see the character in each mountain, setting the stage for the treacherous yet rewarding challenges of the mountaineers in the film, and why they do it.

The film has started its global journey around the prestigious international film festivals, winning the César Awards 2022 for Best Animated Film and nominated in the Annie Awards 2022 so far.

We are happy to share with you the precious story behind the film, from the words of the director Patrick Imbert and the producers, Didier Brunner, Damien Brunner and Thibaut Ruby.

Interview with Patrick Imbert, Didier Brunner, Damien Brunner, and Thibaut Ruby

About the Film Project

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): How did the film project start?

Didier Brunner: The project started when Jean-Charles Ostorero, a mountain fanatic, had bought the rights to Jiro Taniguchi’s manga series for an animation adaptation. He was looking for an experienced co-producer, both executive and delegate, to produce an animated feature film based on that manga.

We met at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival, and the project’s ambition I heard from him immediately seduced me; it was very much in line with our desired editorial line of work. Despite the crazy challenge of adapting a literary and graphic work consisting of five tomes, 200 pages each, into a 90 minute animation, we decided to go on this adventure with Jean-Charles without a second thought.

Today, neither me nor the team at Folivari regrets that decision. It was a challenge that strengthened our desire to make Folivari a tool of excellence to create technically and artistically audacious animated feature films.

HN: What do you think were the keys in realizing this animated feature film project, which needed many business partners, including public and private investors, co-production partners and distributors?

Didier Brunner: To make such a project economically viable in France, it needed a realistic budget (no more than 10 million euros). It also had to be a reasonable economic model without capping the director’s artistic ambitions. To that end, our first demand was to keep most of the fabrication within Fost, our own animation studio.

Unable to finance more than 70% of the film in France, we had to find a trustworthy foreign co-producer that is used to the complex process of “spectacular animation despite a ‘modest’ budget”. Mélusine Productions, a company I’ve worked with for over 25 years now, fitted that requirement. Together, we co-produced Ernest & Célestine, Wolfwalkers, and many other productions. This ideal partner, led by Stéphan Roelants, provided 20% of the financing through Luxembourg’s Film Fund and about the same percentage of the fabrication at Studio 352, their animation studio in Luxembourg.

In France, the key partners are the CNC, Auvergne Rhônes-Alpes region, Île de France region, broadcasters (France 3 Cinéma and Canal+), the distributor Wild Bunch, financial agencies (Soficas) and tax credit. Public founding represents 50% of the French financing (CNC, the two regions and tax credit).

HN: How was the team set up to make the film project feasible?

Thibaut Ruby: The animation industry in France is rapidly expanding, but it’s still a relatively small world. This time, we were looking for members of a niche group within the already small community: specialists of 2D and ‘realism’ animation, a historically sparse animation style in Europe. Also, even though the main team members were relatively easy to identify with the director, we then had to deal with availability issues and it became even harder to form the team. Indeed, the animation style of The Summit of the Gods required people with a very high level of drawing as well as solid animation skills and that was the case with Fost studio in Paris and Studio 352 in Luxembourg. From the very beginning of the project, with the director Patrick, we decided posing would be a major determinant to really set the character models and help us be more serene in our work later on. The production process confirmed that, and even demonstrated that posing is an even more important (and long) process than we initially thought. Especially given the fact we didn’t have the opportunity to make a storyboard as precise as we wanted to.

HN: What kind of difficulties or challenges during the film project were the greatest for you, and how did you overcome them?

Damien Brunner: The Summit of the Gods was a multi-faceted production. The journey has been fascinating on all subjects, such as drawing, lightning, backgrounds, sound, framing, rhythm, colours, and mountaineering technical lingo.

However, this film will always be unique in our career, because right in the middle of the production came COVID-19. There was little risk of an animated character contracting the virus, but the team faced an unknown. Generally speaking, we managed to keep our drive and our objectives, but this challenge wasn’t a ride along a quiet river.

When the world shifted into the sanitary crisis, we predicted the impossibility of keeping the team within the studio. A feeling of foreboding, just a few days before the mandatory lockdown, made us scramble and launch a commando-style operation to ensure animators would be delivered computers, screens, graphic tablets and Cintiqs. We then had to manage technical assistance to set up the remote workflow. Despite a small decline in productivity, production stayed on course, thanks to the team flexibility, the whole production department and the director, who admirably kept the boat afloat during the storm. This film will remain a unique endeavour, both in form and in substance. Unique, because it’s a privilege to produce a film like this one; uncommon, as we did all the animation during a pandemic; and exceptional, because the film is a success.

Film Theme, Message, and Visuals

HN: What is the main message or experience you want to deliver to the audience through this film?

Patrick Imbert: First of all, I want the audiences to come out of the film having had a good time, to not get bored. After that, if they’re touched by the characters and think about the quest of seeking perfection and personal development, then it’s perfect.

HN: Why do you think scaling dangerous mountains captivates climbers like Habu, despite the endeavor being life-threatening? And why do their adventures seem to resonate very well to the general public, in your opinion?

Patrick Imbert: If mountains weren’t dangerous, there wouldn’t be an interest in Habu, nor in the alpinists needing a challenge to live for. Danger is part of the game.

All things considered, we all have our own set of challenges and this is the reason such stories speak to us. And, it must be acknowledged that mountain stories, with everything they bring, adventure, challenges and sometimes even death, are very well suited to melodrama, and by extension, cinema.

HN: What part of the original manga did you find the most attractive, and how did you reflect that into the film?

Patrick Imbert: It was impossible to fit 1,500 pages of manga in a 90 minute film. So, I left out the secondary plots to focus on the two main characters. I’d rather address fewer topics well than to mistreat many. And I felt those characters journey was well-suited for the film structure.

HN: In addition to the previous question, what did you take care in the most when the team is creating the visual design for the film?

Patrick Imbert: A director must pay attention to everything! In my case, I’m first and foremost an illustrator and have been an animator for many years, so I pay special attention to details and precision in the characters representation. An attitude, a side look, a slightly arched back, a head slightly tilted, an inspiration, hesitating fingers, etc., I love to polish those details to make the characters convincing. Working with me can drive animators crazy, so better be prepared (laugh).

HN: Have you had any discussions about the film’s story and visuals with Mr. Taniguchi?

Patrick Imbert: I didn’t get the chance to meet Mr. Taniguchi, but I love his work and I did my best for him to like it and recognize himself into it. Sometimes, when facing a staging problem, I’d imagine having conversations with him to find the best solution. I might be wrong but I like to think he would have liked the end result or at the very least, my efforts to tend towards his universe.

HN: What were the greatest challenges or difficulties you’ve faced, in terms of the creative side of the film project?

Patrick Imbert: Making an animated feature film is a challenge in and of itself, as you never have enough time nor money to do everything you’d want, but it’s also a known fact to professionals within that field. To me the most difficult part, the one that kept me awake at night, is simply narration: to tell a good story. Now that’s a challenge! We tend to forget it because we are surrounded by stories and we consume a lot of them, but telling a good story isn’t that easy.

HN: When it comes to staging with the characters, what were your goals and what did you take special care in?

Patrick Imbert: Like I mentioned before, even the tiniest detail has its importance, everything has a purpose, and nothing is there randomly. Everything has to contribute to the scene’s theme, and it’s true for not only drawings but also for animation. I conceive scenes as a choreography, with every element being set up and animated with a logic akin to a dance.

HN: It was impressive for me that the background art not only portrays the magnificence yet harshness of the mountains in front of the audience, but also sets the mood of each scene effectively.

Could you please let us know the stories behind the creation of the background art for the film, especially where you’ve paid special attention in their artistic direction and for what reasons?

Patrick Imbert: Our goal with the artistic director was to not only describe the mountain but to mostly give it an impression. There was a lot of colour script work to find the different atmosphere within the film, and we worked with photographic references or live action cinema rather than animation, in order to avoid the animation mannerism.

Music

HN: We would like to hear about the story behind the music for the animation that you can share with us. How did Amine Bouhafa get involved with the project?

Patrick Imbert: I didn’t know Amine before, and it was an amazing meeting. We both are “researchers” and it allowed us to get along very well. I had, from the very beginning, the desire to have a score based on two major principles: the first one being the “Hollywood” type, with the music emphasizing emotions, and it is relatively easy to do as you can use the universal codes governing it. For the second one, mostly accompanying the mountain climbing scenes, I wanted something more lunar, undefined, mystic and nature-like; in short a whole lot of intangible stuff. I drew inspiration from progressive rock, Pink Floyd or Alan Parson’s Project. Amine took everything into account and added his own twist to it; he searched a lot and found it. I really love that score.

HN: In addition to the previous question, how was your experience working with Amine, including the composing process and recording?

Patrick Imbert: Working with Amine was super fluid. I had him redo a lot of things but he always had the kindness of not reminding me how much work that was, and he was always listening to my opinions. We saw each other a lot in his small studio to research together. Looking back, I can say his part in the general narration was very important. The recording sessions looked amazing, but because of the pandemic, I sadly couldn’t be there in person, which is really regrettable.