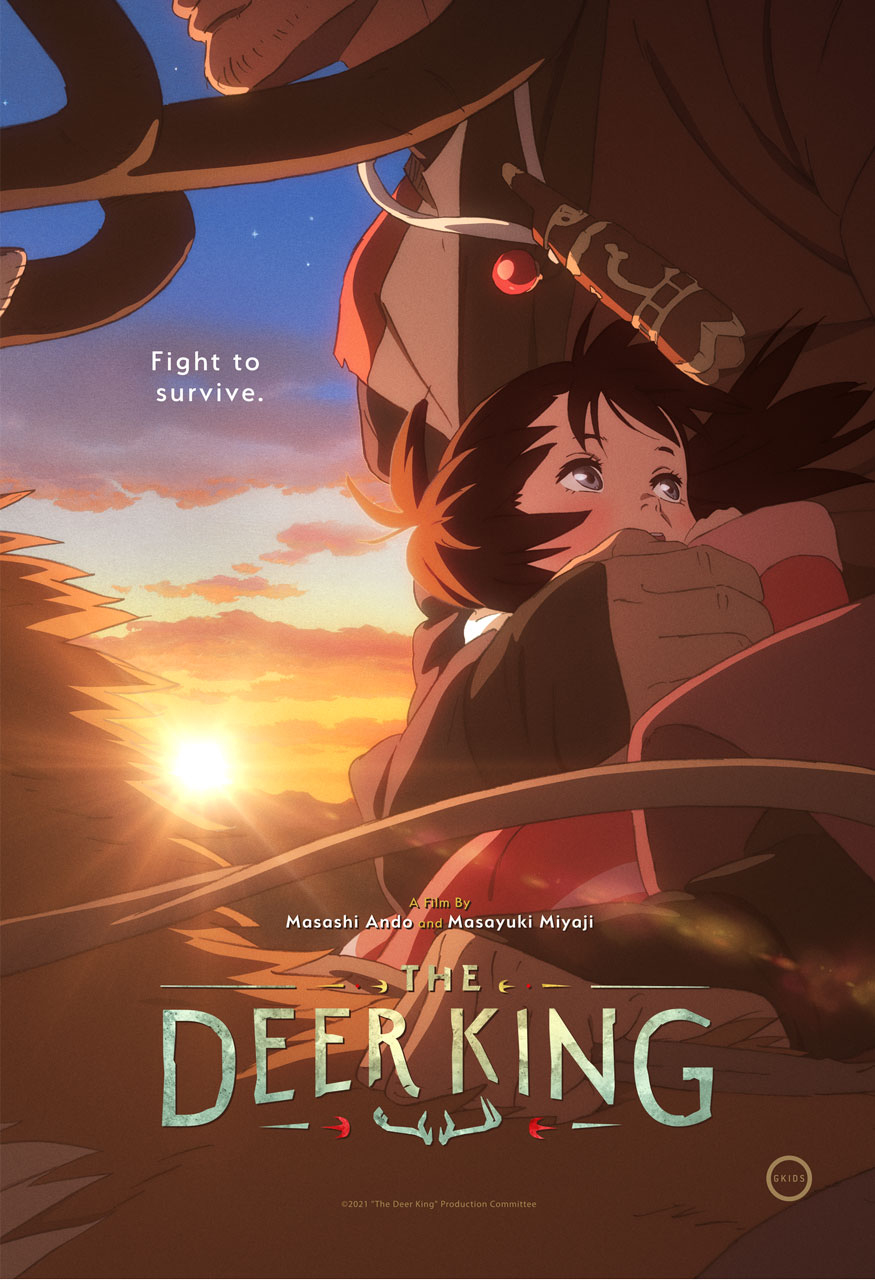

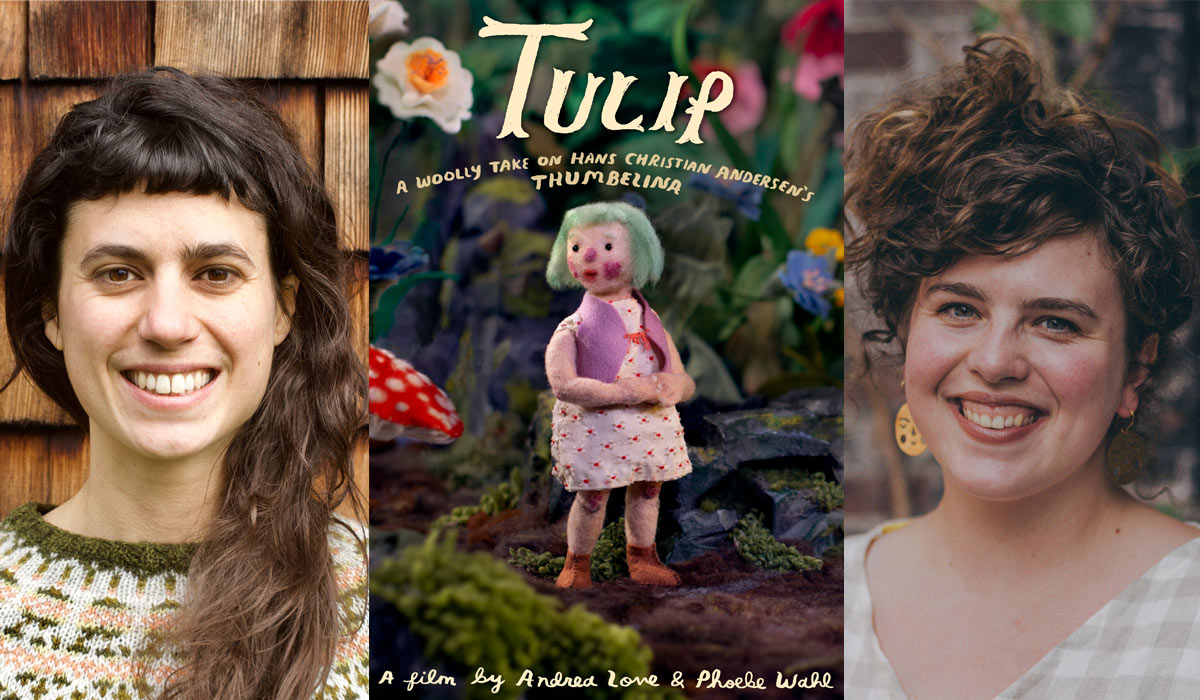

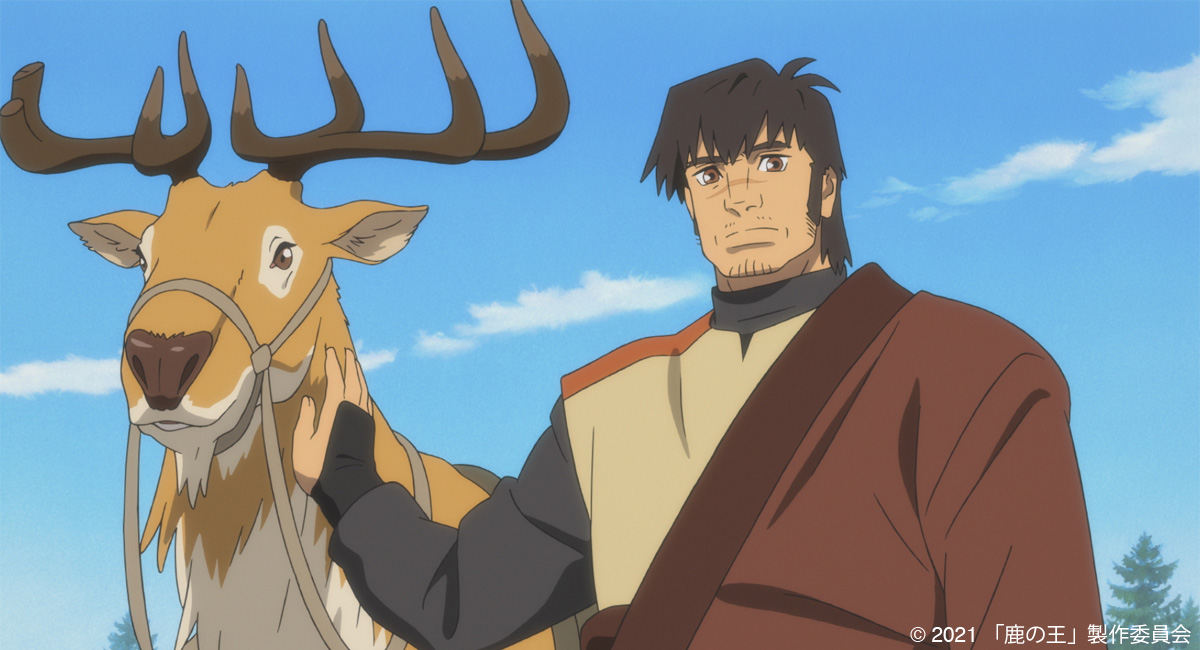

The Deer King

Synopsis

Van, the former leader of a warrior corps who fight for their homeland, is captured and seized as a slave. One night, vicious mountain dogs attack, causing a mysterious plague. Van escapes the chaos, helping a young girl who he decides to raise. Meanwhile, a doctor seeks a cure for this disease.

Film Credits

Directors: Masashi Ando and Masayuki Miyaji

Scriptwriter: Taku Kishimoto (based on The Deer King by Nahoko Uehashi)

Animation Director, Character Designer: Masashi Ando

Art Director: Hiroshi Ohno

Visual Concepts: Hiroki Shinagawa

Music: Harumi Fuuki

Production Studio: Production I.G.

The Deer King is a new and highly-anticipated Japanese 2D animated feature film to be released September in Japan and early 2022 in the US. It had its world premiere at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival 2021 as one of the nominees for “Feature films in competition – Official”.

The film is an animated adaptation of a popular Japanese fantasy novel of the same title written by Nahoko Uehashi. The fantasy adventure story tells a profound and mature story about the complex human relationships among various people with different cultures, religious and agendas, in a setting where a deadly plague has begun to spread. The film project gathered leading animators and background artists, resulting in lifelike and beautiful backgrounds that guides the audience to a rich and detailed fantasy world, accommodating appealing characters with dynamic animation.

The film is directed by two industry veterans with illustrious careers: Masashi Ando and Masayuki Miyaji.

Mr. Ando has worked in Japan as an animation director for several classic animated features such as Hayao Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke (1997) and Spirited Away (2001), Satoshi Kon’s Tokyo Godfathers (2003) and Paprika (2006), and Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name (2016).

Mr. Miyaji is a director famous for his film Fusé: Memoirs of a Huntress (2012) and series Xam’d: Lost Memories (2008).

Both Mr. Ando and Mr. Miyaji’s talents were discovered at a young age by Hayao Miyazaki. Mr. Ando started his career as one of trainees at Studio Ghibli and was selected to become one of the animation directors of Princess Mononoke (1997) when he was only 25 years old. Mr. Miyaji learned staging for animation directly from Hayao Miyazaki at his small group workshop to train young staging directors in his early career and worked for Spirited Away (2001) as an assistant director when he was also just 25 years old.

We had the precious opportunity to hear the insightful story behind the film from Masashi Ando, one of the two directors.

Interview with Masashi Ando

Hideki Nagaishi (HN): On your first read-through of the original novel, what parts of the story attracted you the most? And what characteristics and strengths of animation as a visual storytelling medium have you utilised in adapting the original story for the feature film?

Masashi Ando: I read the novel on the premise of a film adaptation and I was a bit bewildered because the volume of the story and the amount of information contained in it are so huge. I thought it could possibly be a series, but not suitable for a single film.

Additionally, much of the charm of the story from the original novel lies in the dialogue among the characters. So, even if I could faithfully render the dialogue into the film, they would end up being scenes where the protagonists are just talking and there would be no dynamic movement or action. I felt that this would also make it difficult to adapt the novel to a film.

The theme of the original story is deep and wide. However, I thought the novel was too complex to visualize in a film, even though that it’s a good read.

On the other hand, I have recently felt that I had fewer opportunities to come across an animated film with such an expansive and persuasive universe for the story. So, despite the mentioned difficulty of adaptation, my dream of a lore-rich and solid fantasy story, like what we used to admire in the old days, could become a reality with our unique style of animation.

Regardless of how it turned out, I found meaning in the challenge of the film adaptation of the novel, and decided to take part in the film project.

HN: What part of the story did you focus on and what kind things did you take care in to reconstruct a grand story with over 1,100 pages in total into a two-hour story? Did you add any original elements to the film?

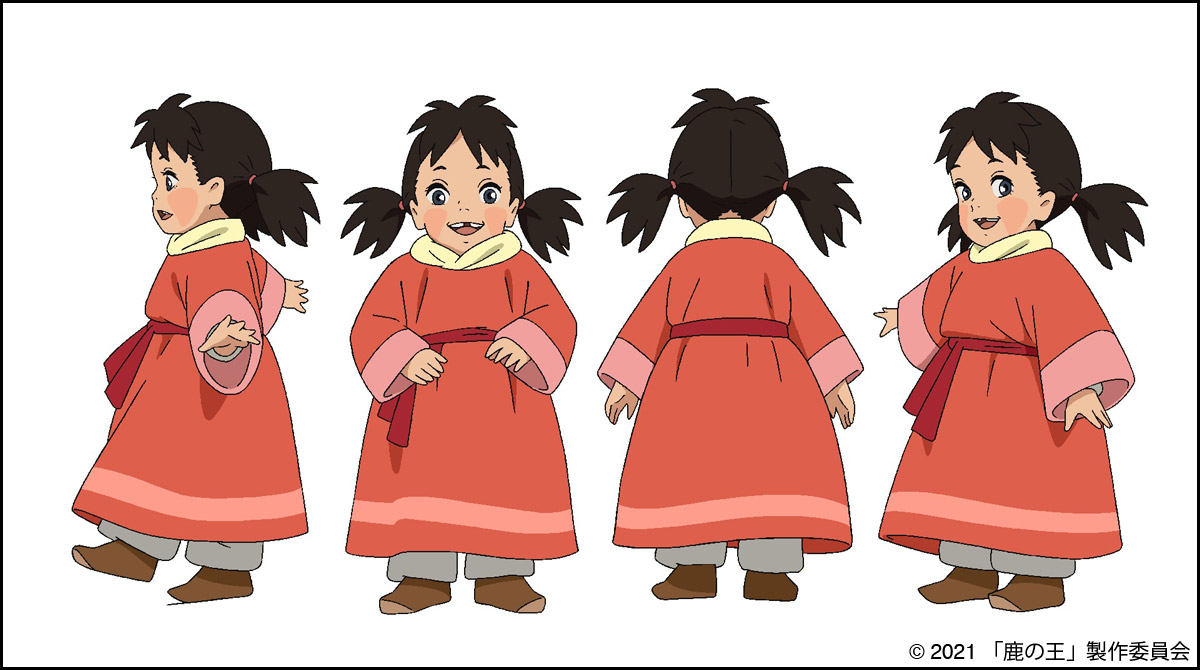

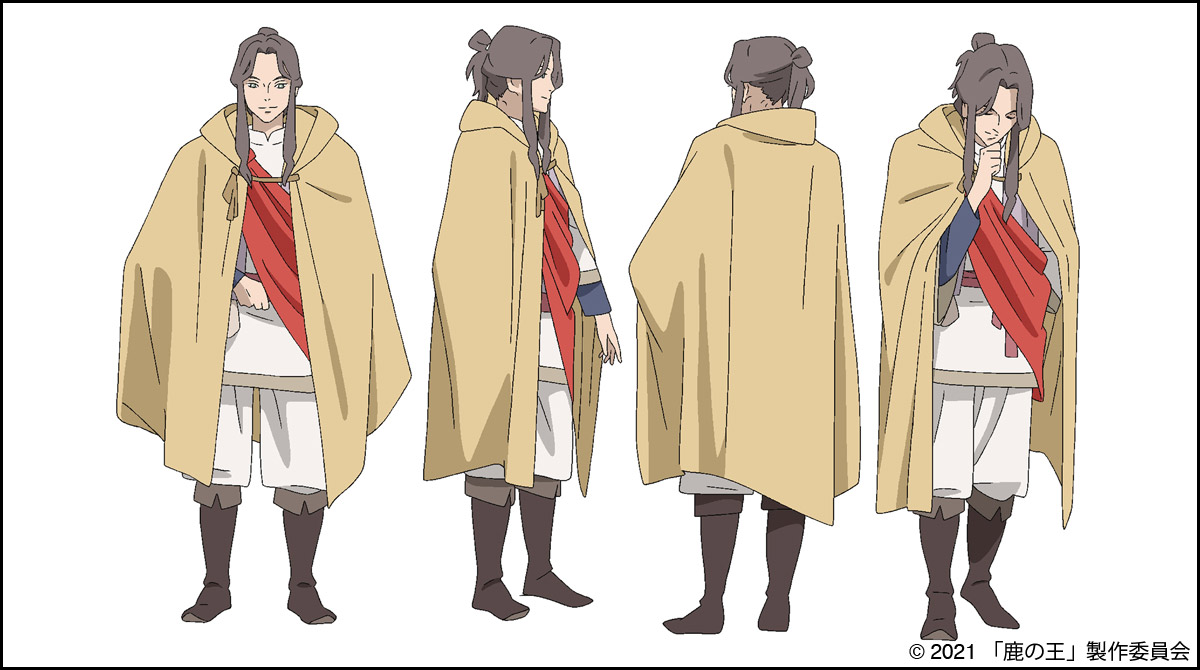

Masashi Ando: In the story of the original novel, the encountering of Van and Yuna is the genesis of the story as well. In the midst of the many victims by a disease full of death, only Van and Yuna overcame the infectious diseases and met each other. I thought that part of the story was very important for the film.

This film is a story that begins with that encounter. And then where will the story of the two characters end up from being tossed about in the complex and muddled web of speculation and intrigue? I thought about structuring the story of the film to centre on Van and Yuna, and the audience will spectate the two characters’ journey until the very end.

So, I thought that if we make the story like the following, it would be a story worth seeing as a feature film:

Hohsalle, a doctor who tries to solve the mystery of the spreading disease, wants Van as the key of the solution. On the other hand, the force that wants to use the disease for their purpose want to kill Van. Furthermore, another new group wants the power residing in Van due to the diseases and chases him. Van and Yuna are at the centre of the story where all these people are going to cross each other, and Van is always watching over Yuna.

In order to have this clear narrative structure, we needed to make some changes from the original novel, such as adding storylines and settings unique to the film, re-arranging the story, and omitting a lot of elements that do not fit the film’s narrative structure.

HN: It was impressive that a lot of information composing the story is interspersed naturally in the conversations among the characters. Thanks to that, I could understand smoothly a wide range of information while enjoying the story, such as the historical relationships between the two countries, the infectious diseases and medical treatment, the relationships among the many characters, and the differences between the thoughts and ideas of the rulers and the commoners.

How did you, Mr. Miyaji, the co-director, and Mr. Kishimoto, the scriptwriter, manage all that information when you were working on the script for the film?

Masashi Ando: Actually, we were quite limited with the information in the film script compare to the original novel. Despite that, we wanted to build the narrative structure that is realizable thanks to the large amount of lore. So, we spent a lot of time struggling with how to get the necessary information for the film story from the original novel.

Mr. Kishimoto, Mr. Miyaaji, Mr. Shingawa (the concept visual designer) and I, came together and exchanged a lot of ideas and opinions in order to reconstruct the story setting and background which makes sense in the film has the scenes to convey that.

Then we had to make a decision on how much information to keep in the film to aid the audience’s understanding, without being too bound to the original story.

So, we made efforts to construct a better scenario by verifying the film’s story over and over again. And what we mean by verify is that we deliberately created multiple opportunities in the film to mention the same thing from different angles, or prepared and arranged scenes that otherwise have nothing in common has some elements in common, which creates a contrast.

HN: This is not only an entertainment film, but also a film with strong social messages.

The film shows us two major issues that are common to all humanity: agendas of rulers which trifle with the citizens, and plague. On the other hand, the film also depicts hope such as people from two countries who overcome their differences and live together with nature, and the parent-child love between Van and Yuna that transcends blood ties.

What do you think about the potential of animation for entertainment business in terms of conveying social messages to the public? And how do you want to reflect that in your films?

Masashi Ando: I believe that the appeal of film, not just animation, is that it broadens the audiences’ horizons of the world.

Not just films of a genre that require deep themes like this film, but also even a film, which seems like a work of unrealistic and strong fictionality at first glance, can depict a truth in its narrative expression. I believe that the discovery of that truth expands the audiences’ perspective of the world. I think having that opportunity is the best part of film making.

By a bizarre coincidence, there are several things in this film that overlap with what we are facing with in the real world today. The epidemic is one of them that has brought to light how divided the world is, based on various factors. In that context, the protagonists struggle, resist and make decisions.

What the protagonists seek is to live together. And “together” is not limited to the physical sense. And I think that we are also seeking to live together in this COVID-19 pandemic. When there is resonance in the phrase “live together” between the film’s audience and the protagonists in the film, I can say that the film has shaped how the audience sees the real world. I hope this film could be such a film.

HN: Some of the fantasy elements in the story that is explained by science and human civilisation, while others are depicted as phenomena that are beyond human comprehension without further clarification. What are your intentions with that?

Masashi Ando: That kind of phenomena depicted in the film is not always seen in the same way by all the characters. If you observe the scenes carefully, you can see that there are differences in the reactions among the people, although we couldn’t clearly portray that.

In other words, not everything in the world is what you see. There is an ability in the film called “Uragaeri”. When we see the real world in general, many of the things appear to exist independently. In contrast, “Uragaeri” is the ability to feel that all the lives in the world are connected, and to find and manipulate the threads which connect them. The ability seems wonderful in one aspect, but on the other side, it is terrifying. At first glance it seems like a supernatural power, but on closer inspection it appears to be connected to science and civilisation when you pursue its nature thoroughly.

Hence, ever since I’ve read the original novel, I have thought continuously that considering the world from multiple perspectives is the most important thing when I think about this story.

HN: What did you focus on and take care in the most in terms of the visual design of the universe for the story and the characters? And what kinds of research did you do for the visual design process?

Masashi Ando: The environment design, costume design, designs arising from the cultures in the story, and so on is largely due to Mr. Shinagawa, who was in charge of the setting for the story’s universe.

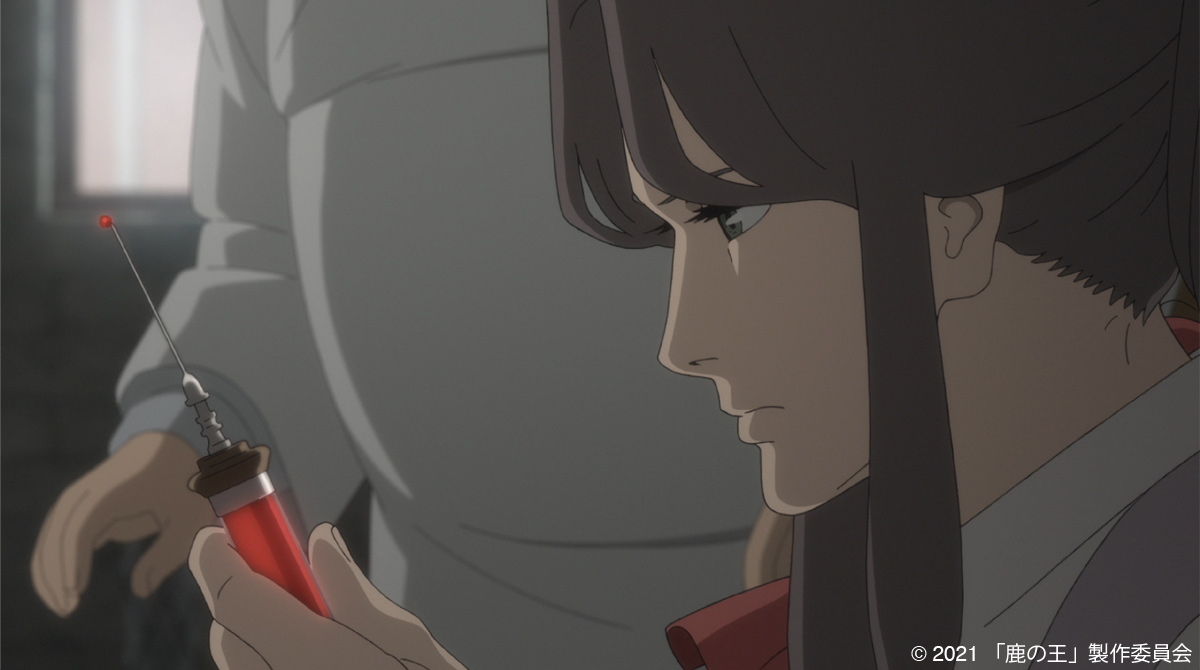

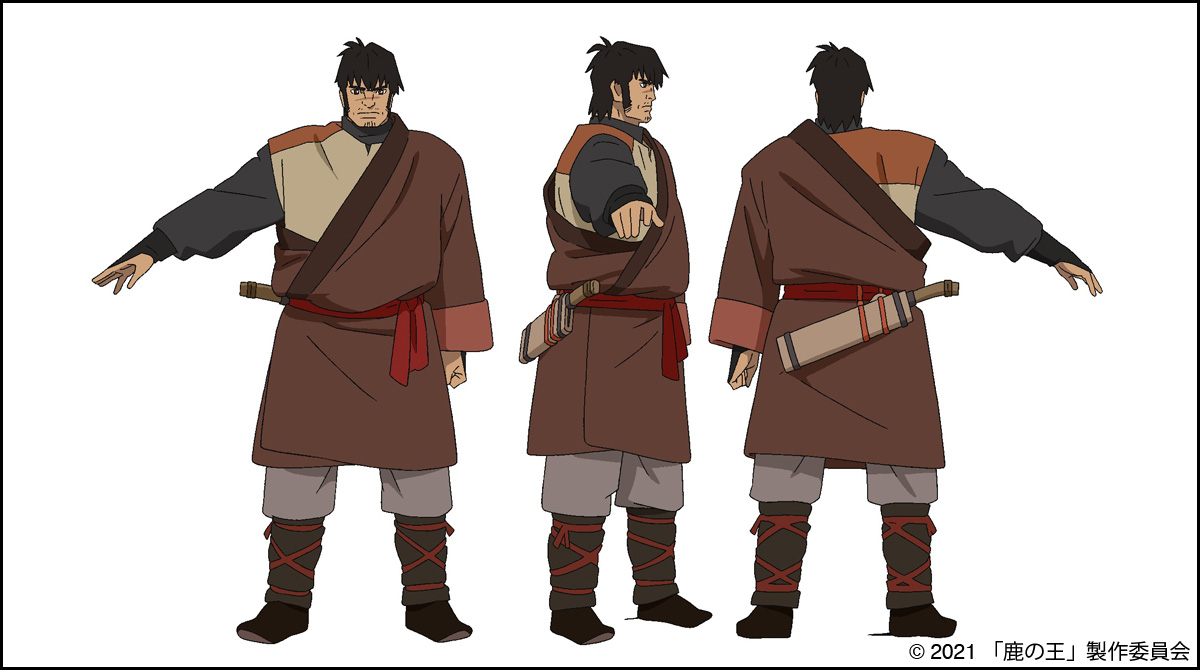

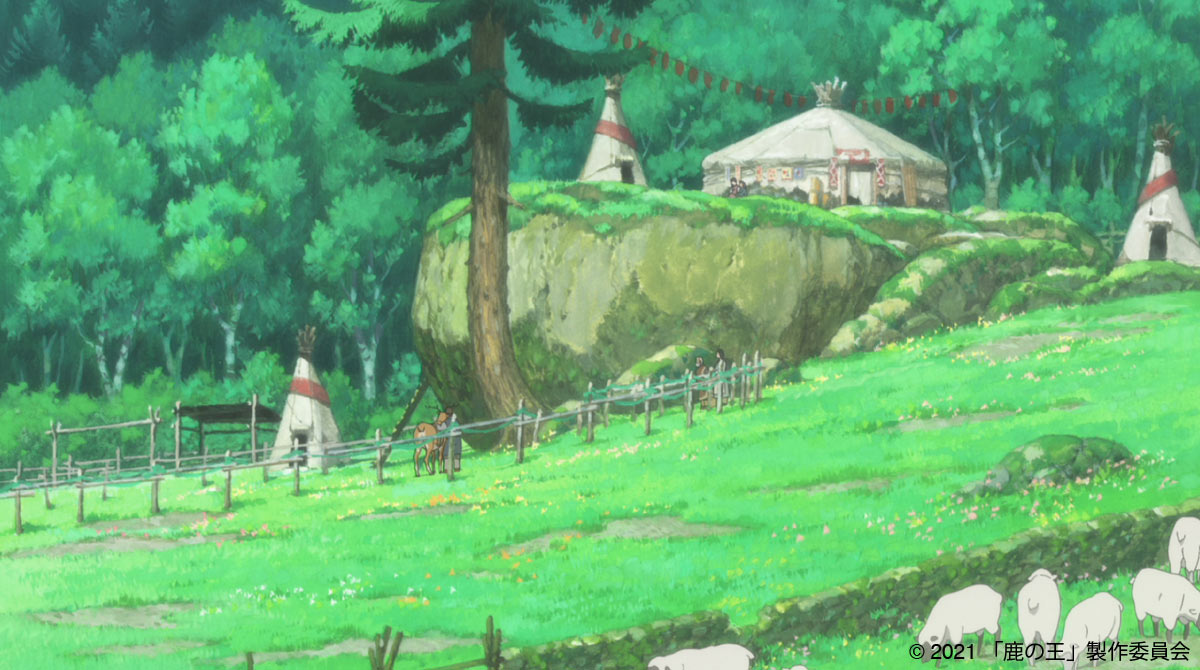

The setting of the Aquafa Kingdom is based on an indigenous farming and herding culture, and the base colours of their costumes and goods are earthly colours. On the other hand, the Zol Empire is designed on the basis of a religion strongly-held in the country. Religious motifs are displayed in many places and are the sustenance of the people’s spiritual world.

Ethnic and cultural differences are important elements of this film and we had to elaborate in many ways to visualise them. For example, it is very difficult to portray ethnic differences only by the characters’ figure, and our intentions with the directing can be misunderstood easily if the visuals take too much influence from racial differences in the real world.

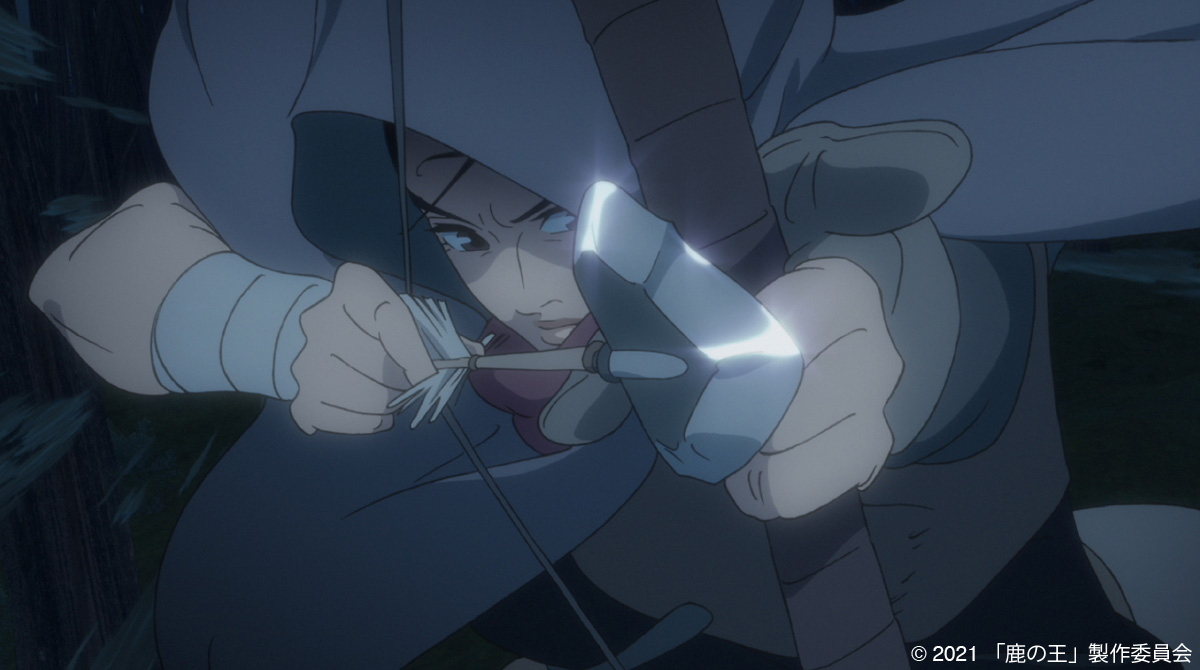

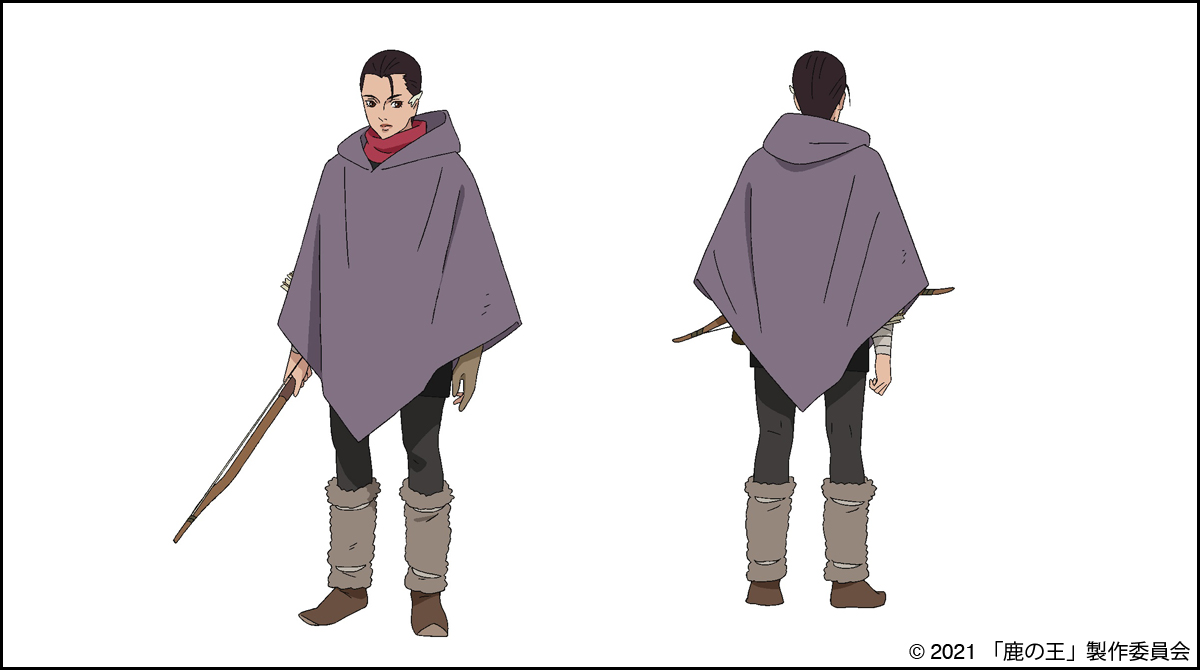

So, for the sake of clarity, we decided that the Zol people will have tattoos on their foreheads. In addition, to make a clear contrast in the cultural backgrounds of Aquafa and Zol, we made “red” and “blue” as the symbolic colours of each of them respectively.

We also took a lot of care in having recognisable contrasts at a glance in each character when we designed their visuals. We thought that if the silhouettes of the characters could make each of their personalities emerge when put next to one another, it was ideal. The basis of our idea for creating the visual differences among the characters, albeit very classical, are circles, triangles and squares.

HN: Hiroshi Ohno, the art director of the film, has worked for multi-award winning animated feature films by leading directors in Japan such as Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children (2012), Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai (2015), and Masaaki Yuasa’s The Night Is Short, Walk on Girl (2017) and Lu over the wall (2017). What do you think is the appeal of the background art directed by Mr. Ohno, including this film, from your point of view?

Masashi Ando: As you know, Mr. Ohno is one of the most trusted art directors in the Japanese animation industry and is a leading artist who draws all styles of background art with excellent skill. I think the greatest attraction of Mr. Ohno’s background art is that, no matter which style he adapted for, all of them are very elegant. I think “delicate and transparent beauty” is the essence and true value of his artwork.

I believe the ending in this film is where Mr. Ohno’s excellent abilities really shined. I think the big factors of that are the fact that he has drawn most of the background in that scene by himself, and we made “a hopeful future” as the motif of that part and it matched his artistic taste.

In fact, the direction of his background art doesn’t seem to line up with stories having a hard edge such as The Deer King. I repeatedly requested him to “have stronger shading” or “make it sharper and edgier” or “make it weirder” during the production process. Even so, his sense of aesthetics took him in the direction of elegance and he seemed to be struggling with responding to my requests.

HN: I encountered many impressive animated moments in this film, such as the action scenes and the lifelike animation of animals. Could you let us know the scenes that you would like the audience to pay special attention to, and the animators who were in charge of those scenes?

Masashi Ando: Above all, I have to mention the chief animator, Toshiyuki Inoue. I have always had nothing but respect and admiration for his work. Once again, he did an outstanding job for this film. In particular, he did great work about animals in general. We asked him to animate the base movements of dogs, horses and flying deer (the Pyuika) ahead of time. And then all the staff used them as a reference when working.

Of course, Mr. Inoue demonstrated his outstanding animation skills not only in the animals, but also for a variety of scenes. These include action scenes such as where a pack of dogs wrapped in black fluids attacks the village where Van is resting, or a cavalry’s suicidal attack in the climax. It also includes important scenes that are low-key and require great deal of effort and time, such as Hohsalle’s first appearance, and the scene where Van climbing up a rope ladder in a salt mine.

To be honest, I often regret that if I had more directing ability, I would’ve been able to make a further leap of the scenes’ expressive power with Mr. Inoue…

I would also like to mention one more animator: Shinji Hashimoto. For instance, there is a scene where Van is chasing after the dogs who kidnapped Yuna; he then desperately reaches out to her but then was intercepted by an arrow shot by Sae in the forest. His work on that scene is vibrant and lively. It is a very powerful scene and that dynamism can be done by no other.

Without a doubt, I’ve truly appreciated the contribution from all the animators, including these two.

HN: What did you focus on or take care of, in terms of the music composition for the film. How was the work with Harumi Fuuki, the composer? And what was your first impression of the completed film with music?

Masashi Ando: To tell you the truth, we ended up having to ask Ms. Fuuki to compose music for the film within a very short period of time due to various reasons, and I am very sorry about that. Nevertheless, all the music she composed and sent us was wonderful and I’m very happy with the music.

What I’ve requested to her when I ordered the music for the film was to have an impressive theme song with a rich melody that symbolises Van, and would stay in the audiences’ head. My vision of the music structure for the film were songs that would represent each scene and character, deriving from Van’s theme song. We focused on melody rather than sound for the film and hoped that the melody would complement the story of the film. As this film has a story that mixes very complex elements, we thought that music would help clarify the core of that complexity.

Ms. Fuuki met our expectations accurately and quickly on a surprising level and I’m sincerely grateful for that.